Chain migration facts for kids

Chain migration is when people from one area move to a new place because others they know have already gone there. This new place can be in another country or just a different part of the same country.

Experts like John S. MacDonald and Leatrice D. MacDonald say that in chain migration, people learn about new chances, get help with travel, and find a place to live and work. This help comes from friends or family who moved earlier. Dara Lind from Vox explains it as: "People are more likely to move to where people they know live." Each new person who moves makes it more likely for their friends and family to follow.

The term "chain migration" became a topic of discussion during debates about immigration rules.

Contents

Communities in New Places

The information and connections that drive chain migration often lead to new communities forming. These communities are like small versions of the places people left behind. Throughout history, especially in the Americas, groups of immigrants have created special neighborhoods called ethnic enclaves. These neighborhoods helped new arrivals settle in and kept their community strong.

Think of places like Kleindeutschland, Little Italy, and Chinatown in the United States. These were all neighborhoods where people from the same background gathered.

This also happened in the countryside in the 1700s and 1800s. Some towns in the Midwestern United States and southern Brazil were even started by immigrants. They would advertise in their home countries to encourage more people to come. For example, New Glarus, Wisconsin in the U.S. and Blumenau, Santa Catarina in Brazil, were founded by German immigrants. Many of these towns spoke German until the mid-1900s in the U.S. and later in Brazil. These communities show how family, community, and immigration are closely linked.

In the late 1800s, many people from specific towns in Italy moved to the United States and Argentina. They used chain migration. At first, Italians from different regions might have lived in separate areas within cities like New York. These communities were often started by men who came for work. Once they earned enough money, many of these men brought their wives and families to their new homes.

Because of laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act and unfair treatment, Chinese immigrants in the U.S. in the late 1800s and early 1900s often stayed together. This led to the growth of Chinatowns. Chain migration, and even "paper sons" (people who used false papers to claim family ties), helped create strong Chinese communities that kept connections with China.

Sending Money Home

Remittances are money sent home by immigrants to their families. This money helps chain migration in two ways: it provides funds and makes others interested in moving.

Researchers Ralitza Dimova and Francois Charles Wolff say that money sent home helps the economies of the immigrants' home countries. But it can also give new migrants the money they need to move. Another study found that people who receive remittances are more likely to think about moving themselves. This is because the money can help with travel costs, and it shows that moving can lead to success.

Besides money, immigrants often sent letters home. These letters shared important information about their new lives, jobs, and tips for other family members or friends who wanted to move. Knowing things like which port to leave from or who to contact for a job and apartment was, and still is, very important for a successful move.

Social Connections

Social capital means the connections and relationships between people that make it easier to do things. In migration, social capital refers to the relationships, knowledge, and skills that help someone move. For example, strong social connections can greatly help people migrate within China.

Experts like Douglas Massey explain that every time someone moves, it creates social capital among the people they know. This makes it more likely for those people to move too. Once enough people in a community have these connections, migration can become a continuous process.

Chain Migration in the United States

Many different groups of immigrants have used chain migration to come to the Americas. This way of moving is common and not limited to certain countries or cultures. For example, Germans escaping problems in Europe in the mid-1800s, Irish people fleeing famine, and Eastern European Jews leaving the Russian Empire all used chain migration. Italians and Japanese also used it to find better economic conditions.

These groups often settled in "colonies" or neighborhoods in cities like Boston, New York, and Buenos Aires. People from the same villages or towns would live close to each other.

Italian immigration in the late 1800s and early 1900s used both chain migration and "return migration." Chain migration helped Italian men move to cities like New York for work. Many Italians left Italy because of tough economic times. They would work in the Americas for a few years and then return home with money. These workers were sometimes called "birds of passage." However, after the Immigration Act of 1924 in the U.S., it became harder to return. This led more Italians to become U.S. citizens. The networks built by chain migration encouraged more Italians to stay permanently. Mexican migration to the U.S. from the 1940s to the 1990s followed similar patterns.

While many Europeans could legally immigrate to the U.S. before the McCarran–Walter Act of 1952, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 stopped almost all Chinese immigration. Still, many Chinese immigrants came to America using false documents. The Chinese Exclusion Act allowed Chinese Americans already in the U.S. to stay and let a small number of their family members immigrate with the right papers. A loophole, and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake that destroyed public records, allowed Chinese immigrants, mostly men, to come with false papers claiming family ties. These were called "paper sons." They relied on chain migration networks to buy documents and learn how to convince officials of their legal status.

Who Migrates?

At first, young, single men were the largest group using chain migration to the United States in the 1800s and early 1900s. But each immigrant group was different, depending on their home country, their reasons for moving, and U.S. immigration laws.

For example, after 1880, more Irish women migrated than men. Both Irish men and women faced economic problems and land issues at home. This led many Irish daughters to leave along with their sons. Italian chain migration started mostly with men who planned to return home. But it later became a way for families to reunite when wives eventually immigrated.

Chinese chain migration was almost entirely male until 1946. That's when the War Brides Act allowed Chinese wives of American citizens to immigrate more easily. Before that, chain migration was limited to "paper sons" and actual sons from China. The uneven number of men and women among Chinese immigrants was due to exclusion laws. These laws made it hard for men to bring their wives or marry and return to the U.S. When people migrate for jobs, chain migration through family ties often helps balance the number of men and women in immigrant communities.

Advertisements for New Homes

In the 1800s and early 1900s, it was common for companies and even U.S. states to advertise to potential European immigrants. These ads in magazines and pamphlets gave immigrants information about travel and where to settle. Much of this advertising aimed to settle land in the Midwestern states after the Homestead Act of 1862. This act gave free land to settlers. So, many ads targeted farmers in Northern and Eastern Europe.

Once chain migration started from a European farm town, the pamphlets, along with letters and money sent from America, made moving an option for more and more people in that community. This chain eventually led to parts of communities moving and creating rural ethnic neighborhoods in the Midwest.

One example is the chain migration of Czechs to Nebraska in the late 1800s. They were drawn by "glowing reports" in Czech newspapers published in Nebraska and sent back home. Railroad companies also advertised large plots of Nebraska land for sale in Czech. Similar ads were read in German areas at the same time, leading to similar chain migration to the Great Plains. These ads showed the "pull factors" (reasons to come). But immigrants also had "push factors" (reasons to leave home), like problems in their own country. The push factors made them want to leave, but the pull factors from ads and letters provided the chain migration structure for their move.

Laws and Migration

Chain migration happens regardless of immigration laws. However, laws do change how it works. Rules about who can enter and how many people are allowed affect who chain migration brings in. But laws that focus on family reunification (letting families join each other) have actually encouraged chain migration through visas for extended family.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and later laws like the Asiatic Barred Zone and the National Origins quota system from the Immigration Act of 1924, tried to limit chain migration. But they couldn't stop it completely. Chinese immigrants found ways around the rules, using loopholes and false documents, until the McCarran—Walter Act of 1952 gave them a small number of visas.

Other immigrant groups were limited by the National Origins quota system. This system set limits based on population ratios from 1890. It favored Western European countries and older immigrant groups like the English, Irish, and Germans. It tried to slow down the number of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe. This quota system allowed some family reunification for chain migration and encouraged immigrants to become citizens. If an immigrant became a U.S. citizen, they could get special visas for more family members. But if they were just a resident, there was a yearly limit. The Immigration Act of 1924 also opened the door for chain migration from the entire Western Hemisphere, placing them outside the quota limits.

The National Origins quota system ended with the Hart–Celler Act of 1965. This law strongly focused on family reunification, setting aside 74% of visas for this purpose. There was no limit for spouses, unmarried minor children, and parents of U.S. citizens. This new law led to a big increase in chain migration and immigration in general. For the first time, more immigrants came from the Third World than from Europe.

Because of the many new immigrants from the Hart–Celler Act and more undocumented immigrants from Mexico, Congress tried to change things. They increased border patrol, offered amnesty (a pardon) for some undocumented immigrants in the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, and suggested limits to family reunification. When the Bracero Program ended, it led to more undocumented Mexican migration. This was because chain migration had made it relatively easy for Mexicans to move, and later laws tried to deal with this.

After 1965

In the United States, the term 'chain migration' is used by people who want to limit immigration. They use it to explain why so many people have legally immigrated since 1965 and where they come from. U.S. citizens and Lawful Permanent Residents (people with "Green cards") can ask for visas for their close relatives like children, spouses, parents, or siblings.

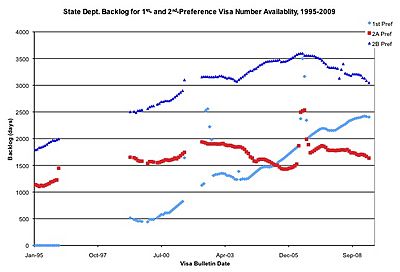

Some people who want less immigration think the family reunification policy is too open. They believe it leads to more immigration than expected and brings in the "wrong type" of immigrants. They would prefer more immigrants with specific job skills. However, the wait times for adult relatives to enter the U.S. can be very long, sometimes 15-20 years. This is because there are limits on how many family-based visas can be given out each year (226,000).

There are four main types of family-based visas:

- First: Unmarried adult children of U.S. citizens.

- Second: Spouses and children, and unmarried adult children of permanent residents.

- Third: Married adult children of U.S. citizens.

- Fourth: Brothers and sisters of U.S. citizens over age 21.

The wait times for these visas can range from about four-and-a-half years to over 20 years, depending on the type of visa and the country the person is from.

While some wait times have stayed the same, others have grown steadily since 1995.

During debates about immigration, especially after a program called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) was ended, the term "chain migration" became a point of disagreement. In 2018, The Associated Press Stylebook, which guides how journalists write, suggested not using the term. They said it was "applied by immigration hardliners to what the U.S. government calls family-based immigration."

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |