Kindertransport facts for kids

The Kindertransport (which means "children's transport" in German) was a special rescue mission. It helped children escape from areas controlled by the Nazis just before World War II started. This happened between 1938 and 1939.

The United Kingdom took in almost 10,000 children. Most of them were Jewish. They came from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the Free City of Danzig. These children found new homes in British foster homes, hostels, schools, and farms. Sadly, many of them were the only ones in their families to survive the Holocaust.

The British government supported this program. They made it easier for the children to enter the country by removing some strict immigration rules. There was no limit to how many children could come. The program ended when World War II began.

A smaller number of children also went to the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Sweden, and Switzerland. Sometimes, the word "Kindertransport" is used more generally for any group of children rescued from Nazi areas. But usually, it refers to the organized program that brought children to the United Kingdom.

Contents

- Helping Children Escape

- How the Rescue Was Organized

- The Journey and End of the Program

- Memorials Along the Kindertransport Route

- After the War

- People Who Helped

- Internment and War Service

- Kindertransport in the United States

- Notable People Saved

- Organizations After the War

- Winton Train

- Images for kids

- See also

Helping Children Escape

On 15 November 1938, five days after Kristallnacht (the "Night of Broken Glass") in Germany and Austria, a group of British, Jewish, and Quaker leaders met with the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Neville Chamberlain. They asked the British government to allow Jewish children to enter the country temporarily, even if their parents could not come with them.

The British government discussed this the next day. They decided to create a plan to let unaccompanied children, from babies up to 17-year-olds, come to Great Britain. There were some conditions, but the government agreed to make the immigration rules easier.

No specific number of children was ever announced publicly. At first, Jewish refugee groups thought they could help 5,000 children. Later, when a request to send 10,000 children to British-controlled Palestine was turned down, this number became an informal goal for Britain.

On 21 November 1938, before a big discussion in the House of Commons, the Home Secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare, met with many groups helping refugees. The government agreed to support the plan proposed by these groups. However, the government would not be responsible for the costs or for finding homes.

The groups, who were working together as the "Movement for the Care of Children from Germany," focused only on rescuing children. These children would have to leave their parents behind. Sir Samuel Hoare said that almost every parent in Germany was willing to send their child alone to the United Kingdom.

Hoare stated that the government would not stop children from coming. But the organizations involved had to find homes for the children. They also had to pay for everything. This was to make sure the children would not become a financial burden on the public. Each child needed a guarantee of £50 sterling to help them move again later, as it was thought they would only stay temporarily.

How the Rescue Was Organized

Soon after the government's decision, the Movement for the Care of Children from Germany (later called the Refugee Children's Movement, or RCM) sent people to Germany and Austria. Their job was to choose, organize, and transport the children. The Central British Fund for German Jewry provided the money for this huge rescue.

On 25 November, people in Britain heard an appeal on the BBC Home Service radio. Viscount Samuel asked for families to offer foster homes. Quickly, 500 offers came in. RCM volunteers visited these homes to check them. They did not require Jewish children to go to Jewish homes. They mainly looked for clean houses and respectable families.

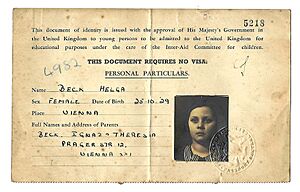

In Germany, volunteers worked very hard to make lists of children who needed help most urgently. This included teenagers in concentration camps or at risk of arrest, Polish children facing deportation, children in Jewish orphanages, or those whose parents were too poor or in concentration camps. Once children were chosen, their parents were given a travel date. Children could only take a small, sealed suitcase with no valuable items and less than ten marks (German money). Some children had only a tag with a number and their name. Others had an identity card with a photo.

The first group of 196 children arrived at Harwich on the TSS Prague on 2 December 1938. This was just three weeks after Kristallnacht. A plaque at Harwich harbor now marks this important event.

Over the next nine months, almost 10,000 unaccompanied children, mostly Jewish, traveled to England.

Other countries also took in Kindertransport children. These included France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark. A Dutch helper named Geertruida Wijsmuller-Meijer arranged for 1,500 children to go to the Netherlands. In Sweden, about 500 Jewish children were given temporary permits. Their parents could not enter the country.

Initially, children came mainly from Germany and Austria. After Germany took over Czechoslovakia on 15 March 1939, transports from Prague were quickly arranged. In February and August 1939, trains from Poland were also organized. Children continued to leave Nazi-occupied Europe until war was declared on 1 September 1939. A few children even flew to Croydon Airport, mostly from Prague.

The Last Transport

The very last transport from the continent with 74 children left on the SS Bodegraven on 14 May 1940. It sailed from IJmuiden, Netherlands. Geertruida Wijsmuller-Meijer organized this departure. She had gathered 66 of the children from an orphanage in Amsterdam. She could have left with them but chose to stay behind. This was a true rescue mission, as the Netherlands was about to be occupied by Germany the next day. This ship was the last one to leave the country freely.

The Netherlands was under attack by German forces. So, there was no chance to talk to the children's parents. At the time, these parents knew nothing about their children being evacuated. Some sources say parents were very upset at first. But after 15 May, no one could leave the Netherlands because the Nazis closed the borders.

The Journey and End of the Program

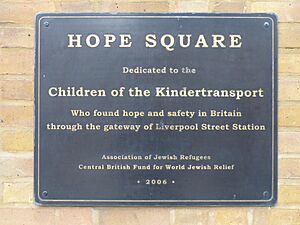

The Nazis ordered that the evacuations must not block German ports. So, most groups traveled by train to the Netherlands. From there, they took a ferry from the Hook of Holland (near Rotterdam) to a British port, usually Harwich. From Harwich, a train took some children to Liverpool Street station in London. There, they met their new foster parents.

Children who did not have foster families waiting were taken to temporary camps. These were places like Dovercourt and Pakefield, which were usually summer holiday camps. Broadreeds holiday camp in Selsey, West Sussex, was used as a temporary camp for girls. While most children traveled by train and boat, some also came by airplane.

The first Kindertransport was organized by Florence Nankivell. She spent a week in Berlin, dealing with Nazi police, to arrange for the children. The train left Berlin on 1 December 1938. It arrived in Harwich on 2 December with 196 children. Most were from a Jewish orphanage in Berlin that the Nazis had burned. Others were from Hamburg.

The first train from Vienna left on 10 December 1938 with 600 children. This was thanks to Geertruida Wijsmuller-Meijer. She had been helping refugees since 1933. She went to Vienna to talk directly with Adolf Eichmann, a high-ranking Nazi. He tried to make it impossible for her to arrange a transport by suddenly "giving" her 600 children. But Wijsmuller-Meijer managed to send 500 children to Harwich. They stayed at a nearby holiday camp in Dovercourt. The other 100 found safety in the Netherlands.

Many people helped the children on their journey. They traveled with the groups from Germany to the Netherlands. Or they met the children at Liverpool Street station in London. They made sure each child was met and cared for. Between 1939 and 1941, 160 children without foster families went to the Whittingehame Farm School in East Lothian, Scotland.

The RCM ran out of money at the end of August 1939. They decided they could not take any more children. The last group of children left Germany on 1 September 1939. This was the day Germany invaded Poland. Two days later, Britain, France, and other countries declared war on Germany. A group tried to leave Prague on 3 September 1939, but they were sent back.

Memorials Along the Kindertransport Route

Artist Frank Meisler created several sculptures to remember the Kindertransport. These sculptures are found along the children's travel route. They show two groups of children and young people waiting for a train, with their backs to each other. The group of rescued children is smaller, reminding us that over a million Jewish children died in the Nazi death camps.

- 2006: Kindertransport – The Arrival at London's Liverpool Street Station. This monument was created at the idea of Prince Charles. It marks where the children from Hook of Holland arrived.

- 2008: Children's Transport Monument. Züge ins Leben – Züge in den Tod: 1938–1939 (Trains to life – trains to death) at Berlin Friedrichstraße station. This remembers the 10,000 Jewish children who traveled from here to London.

- 2009: Kindertransport – Die Abreise (The Departure). In Gdańsk, Poland, Frank Meisler designed another sculpture group. It remembers 124 children who left from there.

- 2011: Crossing Channel to life. This monument is for the 10,000 Jewish children who traveled from Hook of Holland to Harwich.

- 2015: Kindertransport – Der letzte Abschied (The last farewell), at Hamburg Dammtor station.

In September 2022, a bronze memorial called Safe Haven was unveiled on Harwich Quay. It was unveiled by Dame Steve Shirley, who was a Kindertransport child herself. The sculpture shows five Kindertransport refugees coming off a ship. Each child shows a different feeling they might have had at the end of their long journey. The figures also have quotes from four refugees describing their first experience in the UK. This memorial is near where thousands of Kindertransport children first landed.

After the War

After the war ended, it was very difficult for Kindertransport children in Britain to find their families. Agencies received many requests from children looking for their parents or any surviving family members. Some children were able to reunite with their families, sometimes traveling to faraway countries. Others sadly learned that their parents had not survived the war.

People Who Helped

Nicholas Winton

Before Christmas 1938, Nicholas Winton, a 29-year-old British stockbroker, went to Prague. He wanted to help a friend who was working with Jewish refugees. Winton spent three weeks in Prague making a list of children in Czechoslovakia who were refugees from Nazi Germany. He then returned to Britain to arrange for the children to come to Britain and find homes for them.

Trevor Chadwick stayed in Czechoslovakia to lead the children's program there. Winton's mother also helped him find homes and hostels for the children. Winton even placed advertisements asking British families to take them in. A total of 669 children were evacuated from Czechoslovakia to Britain in 1939. This was thanks to the work of Chadwick, Doreen Warriner, Beatrice Wellington, Waitstill and Martha Sharp, and other volunteers. The last group of children, which left Prague on 3 September 1939, was sent back because the Nazis had invaded Poland.

The work of Winton and others in Czechoslovakia was not widely known until 1988. That year, the refugee children held a reunion. By then, most of the people who had worked on the Kindertransport in Czechoslovakia had passed away. Winton became a symbol of British help to refugees escaping the Nazis before World War II.

Wilfrid Israel

Wilfrid Israel (1899–1943) was a very important person in rescuing Jews from Germany. He warned the British government about the upcoming Kristallnacht in November 1938. He also helped British Quakers visit Jewish communities across Germany. This proved to the British government that Jewish parents were indeed willing to let their children go.

Rabbi Solomon Schonfeld

Rabbi Solomon Schonfeld helped bring 300 children who practiced Orthodox Judaism to Britain. He housed many of them in his London home. During the Blitz (bombing of London), he found non-Jewish foster homes for them in the countryside. To make sure the children followed Jewish dietary laws (Kashrut), he told them to tell their foster parents they were "fish-eating vegetarians." He also helped thousands of other young people, rabbis, and teachers come to England.

Internment and War Service

In June 1940, Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, ordered that all male refugees from enemy countries, aged 16 to 70, be held in camps. These were called 'friendly enemy aliens'. Many of the Kindertransport children who were now young men were also held in these camps. About 1,000 of these former Kindertransport children were sent to internment camps, many on the Isle of Man. Around 400 were sent overseas to Canada and Australia.

One ship, the SS Arandora Star, was sunk by a German submarine on 2 July 1940. Many of the people on board were refugees and internees, including former Kindertransport children. Sadly, 805 people died. This event led to British children being evacuated overseas on passenger ships, which were then protected by convoys.

As the young men in the camps turned 18, they were given the chance to do war work or join the Army Auxiliary Pioneer Corps. About 1,000 German and Austrian former Kindertransport children served in the British armed forces. Some even joined special forces units, using their language skills during the Normandy landings and later as the Allies moved into Germany.

Most of the 'friendly enemy aliens' who were interned were refugees who had fled Hitler and Nazism. Nearly all of them were Jewish. When Churchill's policy became known, there was a big discussion in Parliament. Many people were horrified by the idea of holding refugees in camps. Parliament voted to reverse the internment policy.

Kindertransport in the United States

In the United States, the government made it very difficult for refugees to get entrance visas. However, from 1933 to 1945, the United States did accept about 200,000 refugees fleeing Nazism. Most of these refugees were Jewish. This was more than any other country.

In 1939, Senator Robert F. Wagner and Representative Edith Rogers proposed the Wagner-Rogers Bill. This bill would have allowed 20,000 unaccompanied refugee children under the age of 14 to enter the United States from Germany. Most of these children would have been Jewish. However, the bill did not pass.

Notable People Saved

Many children saved by the Kindertransport became famous later in life. Two of them, Walter Kohn and Arno Penzias, even won Nobel Prizes. Here are some others:

- Alfred Dubs, Baron Dubs (from Czechoslovakia), a British politician

- Eva Hesse (from Germany), an American artist

- Sir Peter Hirsch (from Germany), a British metallurgist

- Walter Kohn (from Austria), an American physicist and Nobel Prize winner

- Frank Meisler (from Danzig), an Israeli architect and sculptor

- Arno Penzias (from Germany), an American physicist and Nobel Prize winner

- Dame Stephanie ''Steve'' Shirley (from Germany), a British businesswoman and helper of good causes

- Ruth Westheimer (from Germany), known as "Dr. Ruth," a German-American therapist and talk show host

Organizations After the War

In 1989, Bertha Leverton, who was a Kindertransport child herself, organized a big reunion in London. Over 1,200 people, including Kindertransport survivors and their families, came from all over the world. This was the first event of its kind.

After this, some people from the US formed the Kindertransport Association in 1991. This is an American non-profit organization that connects these child Holocaust refugees and their families. They share their stories, honor those who made the Kindertransport possible, and help children in need today. The Kindertransport Association declared 2 December 2013 as World Kindertransport Day. This was the 75th anniversary of the first Kindertransport arriving in England.

In the United Kingdom, the Association of Jewish Refugees has a special group called the Kindertransport Organization.

Winton Train

On 1 September 2009, a special Winton train left the Prague Main railway station. The train, made of an original locomotive and carriages from the 1930s, traveled to London along the original Kindertransport route. Several surviving Winton children and their families were on board. They were met by Sir Nicholas Winton, who was 100 years old at the time. This event marked 70 years since the last Kindertransport was supposed to leave on 3 September 1939 but was stopped by the start of the war. A statue of Sir Nicholas Winton was unveiled at the Prague railway station when the train departed.

Images for kids

-

Züge ins Leben – Züge in den Tod: 1938–1939 - Trains to Life – Trains to Death, Friedrichstraße station, Berlin

See also

In Spanish: Kindertransport para niños

In Spanish: Kindertransport para niños

- Jews escaping from Nazi Europe to Britain

- Bunce Court School, Otterden, Kent

- Elpis Lodge

- Leica Freedom Train

- Hanna Bergas – one of three teachers to help children arriving at Dovercourt

- Anna Essinger – set up the reception camp at Dovercourt

- Else Hirsch – helped organise ten Kindertransports

- Chiune Sugihara – some 300 Jewish children are estimated to have been saved through his efforts

- Norbert Wollheim – Jewish youth movement leader in Berlin, organised Kindertransports from Berlin

- Œuvre de secours aux enfants

- One Thousand Children

- Hidden children during the Holocaust

- Children in the Holocaust

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |