Adolf Eichmann facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Adolf Eichmann

|

|

|---|---|

Eichmann in 1942

|

|

| Born |

Otto Adolf Eichmann

19 March 1906 |

| Died | 1 June 1962 (aged 56) Ayalon Prison, Ramla, Israel

|

| Nationality |

|

| Other names |

|

| Organization | Schutzstaffel |

| Spouse(s) |

Veronika Liebl

(m. 1935) |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

| Awards |

|

| Allegiance | Nazi Germany |

| Conviction(s) |

|

|

Date apprehended

|

11 May 1960 Buenos Aires, Argentina |

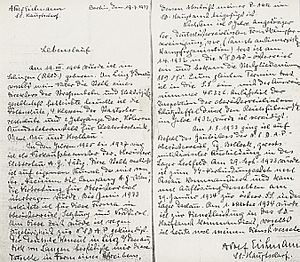

| Signature | |

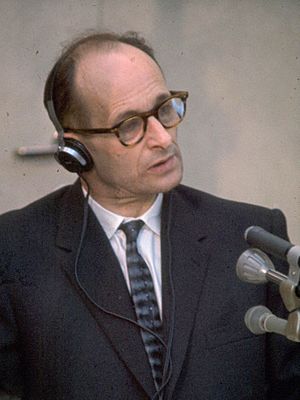

Otto Adolf Eichmann (born March 19, 1906 – died June 1, 1962) was a German-Austrian official of the Nazi Party. He was an officer in the Schutzstaffel (SS), which was a major organization in Nazi Germany. Eichmann was one of the main people who planned and carried out the Holocaust. This was a terrible event where millions of Jews were murdered.

In January 1942, he attended the Wannsee Conference. At this meeting, the Nazis planned how to carry out the "Final Solution." This was their code name for the mass murder of Jewish people. After this, Eichmann was put in charge of moving millions of Jews. He managed the trains and other ways to send them to Nazi ghettos and Nazi extermination camps across Europe.

After World War II ended in 1945, Eichmann was caught by the Allies. However, he managed to escape and later moved to Argentina. In May 1960, agents from Mossad, Israel's intelligence agency, found and captured him. Eichmann was then taken to Israel to face trial. The Eichmann trial was very public and received a lot of attention. He was found guilty in Jerusalem and was executed in 1962.

Eichmann did not do well in school. He worked for his father's mining company for a short time. Later, he became a traveling oil salesman. In 1932, he joined both the Nazi Party and the SS. He moved back to Germany in 1933. There, he joined the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), which was the Nazi Security Service. He became the head of the department that dealt with Jewish affairs. This department focused on making Jews leave Germany, often using violence and economic pressure.

When World War II started in September 1939, Eichmann and his team organized for Jews to be gathered in ghettos in large cities. The plan was to move them further east or overseas. He also made plans for Jewish reservations, but these were never carried out.

On June 22, 1941, the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union. Their policy towards Jews changed from forcing them to leave to planning their murder. Eichmann and his team became responsible for sending Jews to extermination camps. In March 1944, Germany took over Hungary. Eichmann oversaw the deportation of many Hungarian Jews. Most of these victims were sent to Auschwitz concentration camp. About 75 percent of them were killed as soon as they arrived. By July 1944, when the transports stopped, 437,000 of Hungary's 725,000 Jews had been killed.

After Germany lost the war in 1945, Eichmann was captured by U.S. forces. He escaped from a detention camp and moved around Germany to avoid being caught again. He lived in a small village until 1950. Then, he moved to Argentina using fake papers. In 1960, Israel's intelligence agency, Mossad, found him. A team of agents captured Eichmann and brought him to Israel. He was put on trial for many serious charges, including crimes against humanity. During his trial, he did not deny the Holocaust or his role in it. However, he claimed he was only "following orders." He was found guilty of all charges and was executed on June 1, 1962. His trial was widely covered by the media.

Contents

Eichmann's Early Life and School

Otto Adolf Eichmann was born in 1906 in Solingen, Germany. He was the oldest of five children. His family was Protestant. His father, Adolf Karl Eichmann, was a bookkeeper. His mother was Maria Schefferling. In 1913, his father moved to Linz, Austria, for a job. The rest of the family followed a year later. After his mother died in 1916, Eichmann's father remarried.

Eichmann went to the same high school in Linz that Adolf Hitler had attended years before. He played the violin and was involved in sports and clubs. Some older boys in his scouting group were part of right-wing groups. Eichmann did not do well in school. His father took him out of high school and enrolled him in a vocational college. He left college without a degree.

He then worked for his father's mining company for several months. From 1925 to 1927, he worked as a sales clerk for a radio company. After that, from 1927 to early 1933, Eichmann worked as a district agent for the Vacuum Oil Company AG in Austria.

During this time, he joined a youth group linked to a right-wing veterans' movement. He also started reading newspapers published by the Nazi Party. The Nazi Party wanted to get rid of Germany's democratic government. They also wanted to reject the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I. Their beliefs included strong hatred for Jewish people and opposition to communism. They promised a strong government and more "living space" for Germans. They also wanted to remove Jewish people from German society and take away their rights.

Joining the Nazi Party

A family friend, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, who was an SS leader, suggested Eichmann join the Nazi Party. He joined the Austrian branch on April 1, 1932. Seven months later, he joined the SS. His SS group was responsible for guarding party headquarters and protecting speakers at rallies. These rallies often became violent. Eichmann took part in party activities on weekends while still working at Vacuum Oil.

In January 1933, the Nazis took power in Germany. Around the same time, Eichmann lost his job at Vacuum Oil. The Nazi Party was also banned in Austria. These events led Eichmann to return to Germany.

In August 1933, Eichmann attended an SS training program. In September, he was assigned to lead an SS team. This team helped Austrian Nazis enter Germany and smuggled propaganda into Austria. In December, he was promoted to SS-Scharführer (squad leader). His SS battalion was stationed near the Dachau concentration camp.

By 1934, Eichmann asked to be transferred to the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the SS Security Service. He wanted to escape the "boring" military training at Dachau. He was accepted into the SD. He was first assigned to a sub-office that dealt with Freemasons. He organized items for a museum and created a list of German Freemasons. He also helped create an anti-Masonic exhibition, which was very popular.

In November 1934, Eichmann was transferred to the Jewish Department of the SD in Berlin. He later called this his big break. He was tasked with studying and reporting on the Zionist movement and Jewish organizations. He even learned some Hebrew and Yiddish. This helped him become known as an expert on Jewish matters. On March 21, 1935, Eichmann married Veronika Liebl. They had four sons. Eichmann was promoted several times in the SS. In 1937, he left the church.

Nazi Germany used violence and economic pressure to make Jews leave Germany. Between 1933 and 1939, about 250,000 Jews left the country. In 1937, Eichmann traveled to British Mandatory Palestine with his boss, Herbert Hagen. They wanted to see if German Jews could move there voluntarily. They met with a Jewish agent but could not make a deal. Eichmann and Hagen tried to return to Palestine but were not allowed in.

In 1938, Eichmann was sent to Vienna. His job was to help organize Jewish emigration from Austria. Austria had just become part of Germany. Jewish community groups were forced to encourage and help Jews leave. Money for this came from seized Jewish property and donations from other countries. Eichmann was promoted to SS-Obersturmführer (first lieutenant) in July 1938. He was put in charge of the Central Agency for Jewish Emigration in Vienna. By the time he left Vienna in May 1939, nearly 100,000 Jews had left Austria legally. Many more were smuggled out.

World War II and Nazi Plans

From Emigration to Deportation

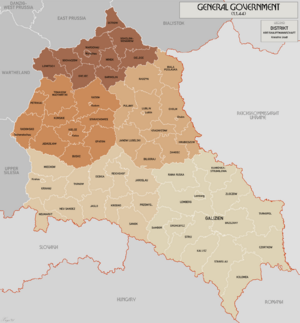

Just weeks after Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, the Nazi policy towards Jews changed. Instead of voluntary emigration, they began forced deportation. On September 21, SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, head of the SD, told his staff that Jews would be gathered in Polish cities with good train connections. This was to make it easier to remove them from German-controlled areas. He also announced plans for a reservation in the General Government (part of Poland not taken by Germany). Jews and others the Nazis disliked would wait there for further deportation.

On September 27, 1939, the SD and the Sicherheitspolizei (SiPo, "Security Police") were combined. They formed the new Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA). Heydrich was in charge of this new office.

After helping set up an emigration office in Prague, Eichmann was moved to Berlin in October 1939. He was put in command of the Reichszentrale für jüdische Auswanderung for the entire German Reich. He was immediately told to organize the deportation of 70,000 to 80,000 Jews from parts of Poland and Moravia. Eichmann also planned to deport Jews from Vienna.

Under the Nisko Plan, Eichmann chose Nisko in Poland as a temporary camp. Jews would stay there before being moved elsewhere. In late October 1939, 4,700 Jews were sent there by train. They were left in an open field with little food or water. The operation was soon stopped. Hitler decided the trains were needed for military purposes. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans were moved into annexed territories. Ethnic Poles and Jews were moved further east, especially into the General Government.

On December 19, 1939, Eichmann was put in charge of RSHA Referat IV D4. This department oversaw Jewish affairs and evacuations. Heydrich called Eichmann his "special expert" for all deportations into occupied Poland. This job involved working with police to remove Jews, dealing with their seized property, and arranging money and transport. Eichmann quickly made a plan to deport 600,000 Jews into the General Government. However, Hans Frank, the governor-general of the occupied territories, did not want to accept so many deportees. He worried it would hurt the region's economy.

Transports continued, but much slower than planned. From the start of the war until April 1941, about 63,000 Jews were sent to the General Government. On many of these trains, up to a third of the people died during the journey. Eichmann claimed at his trial that he was upset by the terrible conditions. However, his papers from that time show he was mainly concerned with making deportations cheap and not disrupting military operations.

Jews were forced into ghettos in large cities. The Nazis expected to move them further east or even overseas later. Conditions in the ghettos were terrible. They were severely overcrowded, had poor sanitation, and lacked food. This led to many deaths. On August 15, 1940, Eichmann wrote a memo called the Madagascar Project. It called for moving a million Jews per year to Madagascar for four years. But Germany failed to defeat the British air force, so the invasion of Britain was put off. Since Britain still controlled the Atlantic Ocean, the Madagascar plan was put on hold. Hitler still mentioned the plan until February 1942, when it was completely dropped.

The Wannsee Conference and Mass Murder

When the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, special groups called Einsatzgruppen followed the army. They rounded up and killed Jews and others. Eichmann received regular detailed reports of their actions. On July 31, Göring gave Heydrich written permission to plan a "total solution of the Jewish question" in all German-controlled areas. This meant coordinating all government groups involved. The Generalplan Ost (General Plan for the East) aimed to deport people from Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union to Siberia. They would be used as slave labor or murdered.

Eichmann later said that Heydrich told him in mid-September that Hitler had ordered all Jews in German-controlled Europe to be killed. Eichmann stated, "I never saw a written order. All I know is that Heydrich told me, 'the Führer ordered the physical extermination of the Jews.'" The first plan was to carry out Generalplan Ost after conquering the Soviet Union. However, after the United States joined the war and Germany failed in the Battle of Moscow, Hitler decided to kill the Jews of Europe immediately. Around this time, Eichmann was promoted to SS-Obersturmbannführer (lieutenant colonel), his highest rank.

To plan the genocide, Heydrich held the Wannsee Conference on January 20, 1942. This meeting brought together Nazi leaders. Eichmann gathered information for Heydrich and attended the conference. He also prepared the official notes of the meeting. Heydrich stated that Eichmann would be his contact person for the departments involved. Under Eichmann's supervision, large-scale deportations to extermination camps began almost immediately. These camps included Bełżec, Sobibor, and Treblinka. The genocide was code-named Operation Reinhard in honor of Heydrich, who died in June.

Eichmann did not make the main policies. He was in charge of carrying out the plans. Specific orders for deportations came from his boss, Gestapo chief Müller, who acted for Himmler. Eichmann's office collected information on Jews in each area. They also organized the seizure of their property and arranged trains. His department worked closely with the Foreign Office. This was because Jews from conquered nations like France could not easily have their possessions taken and be deported. Eichmann held regular meetings in Berlin with his team members working in the field. He also traveled a lot to visit concentration camps and ghettos.

The Occupation of Hungary

Germany invaded Hungary on March 19, 1944. Eichmann arrived the same day. He was soon joined by his top staff and hundreds of SS and SD members. Hitler had appointed a Hungarian government that was more willing to work with the Nazis. This meant that Hungarian Jews, who had been mostly safe until then, would now be sent to Auschwitz concentration camp for forced labor.

Eichmann visited northeastern Hungary in late April. He also went to Auschwitz in May to check on the preparations. At the Nuremberg Trials, Rudolf Höss, the commandant of Auschwitz, said that Himmler told him Eichmann would give all orders for the "Final Solution." Round-ups of Jews began on April 16. From May 14, four trains carrying 3,000 Jews each left Hungary every day. They traveled to Auschwitz II-Birkenau. A new train track ended just a few hundred meters from the gas chambers. Between 10 and 25 percent of the people on each train were chosen for forced labor. The rest were killed within hours of arriving.

Under pressure from other countries, the Hungarian government stopped deportations on July 6, 1944. By this time, over 437,000 of Hungary's 725,000 Jews had died. Despite the orders to stop, Eichmann personally arranged for more trains of victims to be sent to Auschwitz on July 17 and 19.

In a series of meetings starting April 25, Eichmann met with Joel Brand, a Hungarian Jew. Eichmann later said that Berlin had allowed him to let a million Jews leave. In exchange, they wanted 10,000 trucks for the Eastern Front. Nothing came of this offer because the Western Allies refused it. In June 1944, Eichmann was involved in talks that led to the rescue of 1,684 people. They were sent by train to Switzerland in exchange for diamonds, gold, cash, and other valuables.

Eichmann was unhappy that others were getting involved in Jewish emigration. He was also angry that Himmler stopped deportations to the death camps. He asked for a new assignment in July. In late August, he was put in charge of a special squad. Their job was to help evacuate 10,000 ethnic Germans stuck on the Hungarian border. These people were in the path of the advancing Red Army. The Germans they were sent to rescue refused to leave. Instead, the soldiers helped evacuate a German field hospital near the front lines. For this, Eichmann received the Iron Cross, Second Class.

Throughout October and November, Eichmann arranged for tens of thousands of Jewish victims to be forced to march. They walked in terrible conditions from Budapest to Vienna, a distance of 210 kilometers (130 miles).

On December 24, 1944, Eichmann fled Budapest just before the Soviets surrounded the capital. He returned to Berlin. There, he arranged for the important records of his department to be burned. Like many other SS officers who fled as the war ended, Eichmann and his family were living safely in Austria when the war in Europe finished on May 8, 1945.

After World War II: Hiding and Capture

After the war, Eichmann was captured by U.S. forces. He spent time in several camps for SS officers. He used fake papers that said his name was Otto Eckmann. He escaped from a work group when he realized his real identity had been discovered. He got new identity papers with the name Otto Heninger. He moved often over the next few months. He finally settled in Altensalzkoth, Germany, where he lived until 1950. Meanwhile, Rudolf Höss, the former commandant of Auschwitz, and others gave damaging evidence about Eichmann at the Nuremberg trials starting in 1946.

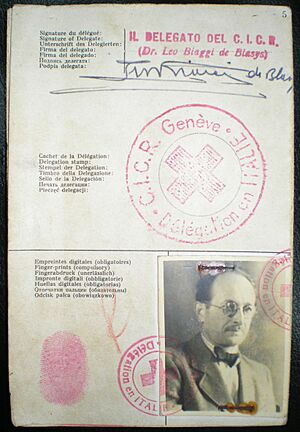

In 1948, Eichmann got permission to enter Argentina. He also got fake identification under the name Ricardo Klement. He received help from an organization led by Bishop Alois Hudal, an Austrian priest who supported the Nazis. These documents helped him get a Red Cross humanitarian passport. He got the rest of the papers needed to move to Argentina in 1950. He traveled across Europe, staying in safe houses set up in monasteries. He left Genoa by ship on June 17, 1950, and arrived in Buenos Aires on July 14.

Eichmann first lived in Tucumán Province, where he worked for a government contractor. He sent for his family in 1952, and they moved to Buenos Aires. He had several low-paying jobs. Then he found work at Mercedes-Benz, where he became a department head. The family built a house and moved in during 1960.

Eichmann was interviewed for four months starting in late 1956. A Nazi journalist named Willem Sassen wanted to write a biography. Eichmann provided tapes, notes, and handwritten papers. The audio recordings became public in 2022. Eichmann admitted that he knew millions of Jews were being killed. He said, "I didn't care about the Jews deported to Auschwitz, whether they lived or died. It was the Fuehrer's order: Jews who were fit to work would work and those who weren't would be sent to the Final Solution." When Sassen asked if "Final Solution" meant they should be killed, Eichmann replied, "Yes."

These interviews were used for articles in Life and Stern magazines in late 1960. The Sassen tapes are also part of a documentary series called The Devil's Confession: The Lost Eichmann Tapes, shown in 2022.

Eichmann's Capture in Argentina

Many survivors of the Holocaust wanted to find Eichmann and other Nazis. One of them was Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal. In 1953, Wiesenthal learned that Eichmann had been seen in Buenos Aires. He gave this information to the Israeli consulate in Vienna in 1954. Eichmann's father died in 1960. Wiesenthal arranged for private detectives to secretly photograph Eichmann's family members. Eichmann's brother Otto looked very much like him, and there were no recent photos of Eichmann. Wiesenthal gave these photos to Mossad agents on February 18.

Lothar Hermann, a Jewish German who moved to Argentina in 1938, also helped find Eichmann. His daughter Sylvia started dating a man named Klaus Eichmann in 1956. Klaus boasted about his father's Nazi actions. Hermann told Fritz Bauer, a prosecutor in West Germany. Hermann then sent his daughter to gather more information. Eichmann himself answered the door and said he was Klaus's uncle. However, Klaus arrived soon after and called Eichmann "Father." In 1957, Bauer personally gave the information to Mossad director Isser Harel. Mossad agents started watching Eichmann, but at first, they found no clear proof. Bauer did not trust the German police or legal system. He feared they might warn Eichmann. So, he decided to go directly to Israeli authorities. Also, when Bauer asked the German government to get Eichmann from Argentina, they immediately said no. The Israeli government paid Hermann a reward in 1971, twelve years after he gave the information. A German geologist named Gerhard Klammer, who worked with Eichmann in the early 1950s, gave Bauer Eichmann's address and a photo. Klammer's identity was only revealed in 2021.

Harel sent Shin Bet chief interrogator Zvi Aharoni to Buenos Aires on March 1, 1960. After several weeks, Aharoni confirmed Eichmann's identity. Argentina had a history of refusing to hand over Nazi criminals. So, instead of asking for extradition, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion decided Eichmann should be captured and brought to Israel for trial. Harel arrived in May 1960 to oversee the capture. Mossad agent Rafi Eitan led the eight-man team.

The team captured Eichmann on May 11, 1960. This happened near his home in San Fernando, Buenos Aires. The agents had arrived in April and watched his daily routine for many days. They noticed he usually came home from work by bus at the same time each evening. They planned to grab him as he walked from the bus stop to his house. The plan was almost canceled on the chosen day because Eichmann was not on his usual bus. But he got off another bus about half an hour later. Mossad agent Peter Malkin approached him. Eichmann was scared and tried to leave. But two more Mossad men helped Malkin. The three wrestled Eichmann to the ground. After a struggle, they moved him to a car and hid him on the floor under a blanket.

Eichmann was taken to one of the Mossad safe houses. He was held there for nine days. During this time, his identity was checked and confirmed. Harel also tried to find Josef Mengele, a terrible Nazi doctor from Auschwitz. Mossad had information that Mengele was also living in Buenos Aires. Harel hoped to bring Mengele back to Israel on the same flight. However, Mengele had already left his last known home in the city. Harel had no more clues, so the plans to capture Mengele were dropped. Eitan later said in 2008 that the team decided not to go after Mengele. They feared it might put the Eichmann operation at risk.

Near midnight on May 20, an Israeli doctor, part of the Mossad team, gave Eichmann a sedative. Eichmann was dressed as a flight attendant. He was secretly taken out of Argentina on the same El Al plane that had carried Israel's delegation a few days earlier. This delegation had attended a celebration in Argentina. There was a tense delay at the airport while the flight plan was approved. Then the plane took off for Israel. It stopped in Dakar, Senegal, to refuel. They arrived in Israel on May 22. The next afternoon, Prime Minister Ben-Gurion announced Eichmann's capture to the Knesset (Israel's parliament).

In Argentina, news of the capture led to a wave of anti-Jewish violence. This was carried out by far-right groups. Argentina asked for an urgent meeting of the United Nations Security Council in June 1960. This was after talks with Israel failed. Argentina saw the capture as a violation of their country's rights. In the debate, Israeli representative Golda Meir (who later became prime minister) said the captors were not Israeli agents but private individuals. She said it was just an "isolated violation of Argentine law." On June 23, the Council passed Resolution 138. It agreed that Argentina's rights had been violated and asked Israel to make amends. Israel and Argentina issued a joint statement on August 3. After more talks, they admitted the violation but agreed to end the dispute. The Israeli court ruled that how Eichmann was captured did not affect the legality of his trial.

Documents from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) released in 2006 showed that Eichmann's capture worried the CIA and West German intelligence. Both organizations had known for at least two years that Eichmann was hiding in Argentina. But they did not act because it did not help their interests in the Cold War. Both were worried about what Eichmann might say in his testimony about a West German national security advisor. This advisor had helped write several anti-Jewish Nazi laws. The documents also showed that both agencies had used some of Eichmann's former Nazi colleagues to spy on communist countries in Europe.

Eichmann's Trial in Jerusalem

Eichmann was taken to a strong police station in Yagur, Israel. He stayed there for nine months. The Israelis did not want to put him on trial based only on documents and witness statements. So, he was questioned daily. The transcripts of these questions filled over 3,500 pages. The main questioner was Chief Inspector Avner Less of the national police. Less used documents from Yad Vashem (a Holocaust memorial) and Nazi hunter Tuviah Friedman. He could often tell when Eichmann was lying or avoiding answers. When more information came out that forced Eichmann to admit what he had done, Eichmann would say he had no power in the Nazi system. He claimed he was only following orders. Inspector Less noted that Eichmann did not seem to understand how terrible his crimes were. He showed no regret. In his plea for pardon, released in 2016, Eichmann wrote: "There is a need to draw a line between the leaders responsible and the people like me forced to serve as mere instruments in the hands of the leaders. I was not a responsible leader, and as such do not feel myself guilty."

Eichmann's trial began on April 11, 1961, before a special court in Jerusalem. The charges against him were based on the 1950 Nazi and Nazi Collaborators (Punishment) Law. He was charged with 15 crimes, including crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crimes against the Jewish people. He was also charged with being a member of a criminal organization. Three judges oversaw the trial: Moshe Landau, Benjamin Halevy, and Yitzhak Raveh. The chief prosecutor was Israeli Attorney General Gideon Hausner. His defense team included German lawyer Robert Servatius. At the time, foreign lawyers could not represent people in Israeli courts. But Israeli law was changed to allow non-Israeli lawyers for those facing death penalty charges.

The Israeli government made sure the trial had wide media coverage. An American company got the exclusive rights to videotape the proceedings for television. Many major newspapers worldwide sent reporters and published front-page stories. The trial was held in an auditorium in central Jerusalem. Eichmann sat inside a bulletproof glass booth to protect him. The building was changed so journalists could watch the trial on closed-circuit television. There were 750 seats in the auditorium. Videotapes were flown daily to the United States for broadcast the next day.

The prosecution presented its case for 56 days. They used hundreds of documents and called 112 witnesses, many of whom were Holocaust survivors. Hausner wanted to show Eichmann's guilt and also present information about the entire Holocaust. His opening speech began, "It is not an individual that is in the dock at this historic trial and not the Nazi regime alone, but anti-Semitism throughout history." Eichmann's lawyer tried to limit the information not directly related to Eichmann, and was mostly successful. Evidence included wartime documents, tapes, and notes from Eichmann's questioning and interviews in Argentina.

The prosecution showed that Eichmann had visited places where killings happened. These included Chełmno extermination camp, Auschwitz, and Minsk (where he saw a mass shooting of Jews). This proved he knew that the deported people were being killed.

The defense then questioned Eichmann for a long time. Observers noted Eichmann's ordinary appearance and lack of emotion. In his testimony, Eichmann insisted he had no choice but to follow orders. He said he was bound by an oath to Hitler. This was the same defense used by some Nazis at the Nuremberg trials. Eichmann claimed that the decisions were made by his superiors, not by him. He also argued that the Nazi government's decisions were "acts of state" and not subject to normal court rules. About the Wannsee Conference, Eichmann said he felt satisfied and relieved afterward. He felt that since his superiors had made a clear decision to kill, the matter was out of his hands. He felt no guilt. On the last day of his questioning, he said he was guilty of arranging the transports. But he did not feel guilty for what happened as a result.

During his cross-examination, prosecutor Hausner tried to get Eichmann to admit personal guilt. But Eichmann never did. Eichmann admitted he did not like Jews and saw them as enemies. But he said he never thought their complete destruction was right. Hausner showed evidence that Eichmann had said in 1945, "I will leap into my grave laughing because the feeling that I have five million human beings on my conscience is for me a source of extraordinary satisfaction." Eichmann first said he meant "enemies of the Reich" like the Soviets. But later, when questioned by the judges, he admitted he meant the Jews. He said the remark truly showed his opinion at the time.

The trial ended on August 14. The verdict was read on December 12. Eichmann was found guilty of 15 charges. These included crimes against humanity, war crimes, crimes against the Jewish people, and being a member of a criminal organization. The judges said he did not personally kill anyone. They also said he did not oversee the actions of the Einsatzgruppen. However, he was found responsible for the terrible conditions on the deportation trains. He was also responsible for getting Jews to fill those trains. Besides crimes against Jews, he was found guilty of crimes against Poles, Slovenes, and Roma people. Eichmann was also found guilty of being a member of three organizations declared criminal at the Nuremberg trials: the Gestapo, the SD, and the SS. When deciding the sentence, the judges concluded that Eichmann was not just following orders. They believed he fully supported the Nazi cause and was a key person in the genocide. On December 15, 1961, Eichmann was sentenced to death.

Appeals and Execution

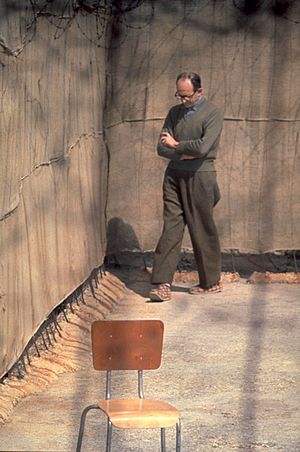

Eichmann's lawyers appealed the verdict to the Israeli Supreme Court. Five Supreme Court judges heard the appeal from March 22 to 29, 1962. The defense mainly argued about Israel's right to try him and the legality of the laws used. Eichmann's wife, Vera, flew to Israel and saw him for the last time in late April. On May 29, the Supreme Court rejected the appeal. It upheld the District Court's judgment on all counts. Eichmann immediately asked Israeli President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi for mercy. His letter and other trial documents were made public on January 27, 2016. In his letter, Eichmann asked for a pardon. His lawyer, wife, and brothers also wrote to President Ben-Zvi asking for mercy. Some important people spoke against the death penalty. Ben-Gurion called a special cabinet meeting to decide. The cabinet decided to recommend that President Ben-Zvi not grant Eichmann mercy. Ben-Zvi rejected the request for mercy. At 8:00 p.m. on May 31, Eichmann was told that his request for presidential mercy had been denied.

Eichmann was executed at a prison in Ramla hours later. The execution was planned for midnight on May 31. It was slightly delayed and happened a few minutes after midnight on June 1, 1962. A small group of officials, four journalists, and a Canadian clergyman attended the execution. The clergyman had been Eichmann's spiritual advisor in prison. His last reported words were: "Long live Germany. Long live Argentina. Long live Austria. These are the three countries with which I have been most connected and which I will not forget. I greet my wife, my family and my friends. I am ready. We'll meet again soon, as is the fate of all men. I die believing in God."

Rafi Eitan, who was with Eichmann at the execution, claimed in 2014 that he later heard Eichmann mumble, "I hope that all of you will follow me."

Within hours, Eichmann's body was cremated. His ashes were scattered in the Mediterranean Sea, outside Israeli waters, by an Israeli Navy patrol boat.

Eichmann's youngest son, Ricardo Eichmann, has said he does not resent Israel for executing his father. He does not agree that his father's "following orders" argument excuses his actions. He noted that his father's lack of regret caused "difficult emotions" for the Eichmann family. Ricardo was a professor of archaeology until 2020.

What Happened After the Trial

The trial was widely covered by the press in West Germany. Many schools added material about the issues to their lessons. In Israel, the witnesses' stories at the trial helped people understand the impact of the Holocaust on survivors much better, especially younger citizens. The trial helped to change the idea that Jews had gone "like sheep to the slaughter" without resistance.

The idea of "Eichmann" as a type of person comes from Hannah Arendt's idea of the "banality of evil". Arendt, a political thinker who reported on Eichmann's trial, described him in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem. She thought he seemed like an ordinary person, showing no guilt or hatred. She used the phrase "banality of evil" to describe this. In his 1988 book, Wiesenthal said: "The world now understands the concept of 'desk murderer'. We know that one doesn't need to be fanatical or mentally ill to murder millions; that it is enough to be a loyal follower eager to do one's duty." The term "little Eichmanns" became a negative term for people in charge who indirectly and systematically harm others.

In her 2011 book Eichmann Before Jerusalem, Bettina Stangneth argued that Eichmann was not a simple bureaucrat. She said he was an antisemite who believed strongly in Nazi ideas. She believed he pretended to be a faceless bureaucrat for his trial. Historians like Christopher Browning, Deborah Lipstadt, Yaacov Lozowick, and David Cesarani came to a similar conclusion. They believed Eichmann was not the thoughtless official Arendt believed him to be.

See also

In Spanish: Adolf Eichmann para niños

In Spanish: Adolf Eichmann para niños

- Command responsibility

- List of Nazi Party leaders and officials

- List of SS personnel

- Superior orders

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |