Joel Brand facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Joel Brand

|

|

|---|---|

Brand in 1961

|

|

| Born | 25 April 1906 Naszód, Austria-Hungary (now Năsăud, Romania)

|

| Died | 13 July 1964 (aged 58) |

| Resting place | Tel Aviv, Israel |

| Known for | "Blood for goods" proposal |

| Spouse(s) | Haynalka "Hansi" Brand (née Hartmann) |

Joel Brand (Hungarian: Brand Jenő; 25 April 1906 – 13 July 1964) was a brave member of a secret Jewish group in Budapest, Hungary. This group was called the Aid and Rescue Committee. During the Holocaust, they helped Jewish people escape from parts of Europe controlled by Germany. They smuggled them to safer places like Hungary.

In March 1944, Germany took over Hungary. Joel Brand became known for trying to save Jewish people from being sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. This camp was in Poland, and many people were killed there.

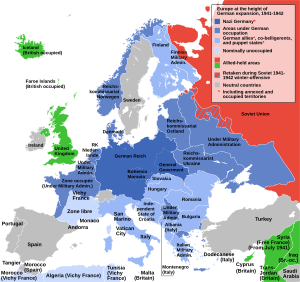

In April 1944, a German officer named Adolf Eichmann met with Brand. Eichmann was in charge of Jewish affairs for the Germans. He suggested a shocking deal: The Germans would let one million Jewish people go free. In return, the United States or Britain would give them 10,000 trucks, plus tea and other supplies. Eichmann called this deal "Blut gegen Waren," which means "blood for goods."

This idea never happened. The Times newspaper in London called it one of the worst stories of the war. Some historians think the Germans, especially their leader Heinrich Himmler, used these talks as a way to try and make peace with the Western Allies (like the US and Britain) without including the Soviet Union. The British government stopped the plan. They arrested Joel Brand in Aleppo (which was under British control). He had gone there to tell Jewish leaders about Eichmann's offer. The British then told the news to everyone, ending the deal.

The failure of this plan, and why the Allies couldn't save the 437,000 Hungarian Jews sent to Auschwitz in 1944, was debated for many years. In 1961, Life magazine said Brand was "a man who lives in the shadows with a broken heart." He said before he died in 1964: "An accident of life placed the fate of one million human beings on my shoulders. I eat and sleep and think only of them."

Contents

Joel Brand's Early Life and Work

Growing Up in Europe

Joel Brand was one of seven children. He was born into a Jewish family in Naszód, which was part of Austria-Hungary (now Năsăud, Romania). His father started the telephone company in Budapest. His grandfather owned the post office in Munkács (now Mukacheve, Ukraine).

When Joel was four, his family moved to Erfurt, Germany. At 19, he went to New York to stay with an uncle. He traveled across the United States, working different jobs. He joined the Communist Party and worked as a sailor, traveling to many countries.

Around 1930, Brand returned to Erfurt. He worked for another telephone company his father had started. He also became involved with the Communist Party in Germany. In 1933, he was arrested because he was a communist. After being released in 1934, he moved to Budapest, Hungary. There, he worked for his father's company again. He also joined a Zionist party called Poale Zion. This group helped Jewish people move to Palestine.

Helping Others: The Aid and Rescue Committee

In 1935, Joel Brand married Haynalka "Hansi" Hartmann. They opened a factory that made knitwear and gloves in Budapest. After a few years, they had over 100 employees. Joel and Hansi had planned to move to Palestine. But Joel's mother and three sisters fled Germany and came to Budapest, so he needed to support them.

Joel Brand started helping Jewish people escape to Hungary in 1941. This happened after Hansi's sister and brother-in-law were caught in a terrible event called the Kamianets-Podilskyi massacre. Thousands of Jews were killed there. Brand paid a Hungarian officer to bring his wife's relatives back safely.

Through their political party, the Brands joined other Zionists who were trying to save people. These included Rezső Kasztner, a lawyer, and Ottó Komoly, an engineer. In 1943, this group formed the Aid and Rescue Committee. It was also known as the Va'ada. Ottó Komoly was the leader.

The Va'ada raised money, made fake documents, and ran safe houses. Joel Brand later said that between 1941 and the German invasion in 1944, he and the committee helped 22,000 to 25,000 Jewish people reach Hungary.

One of their contacts was Oskar Schindler. He smuggled letters and money into the Kraków ghetto for them. In 1943, Schindler visited Budapest. The committee learned that he was bribing Nazi officers. He did this to bring Jewish refugees into his factory in Poland, which was a safe place. This encouraged the committee to try talking with the German SS after Hungary was invaded.

The "Blood for Goods" Proposal

Germany Invades Hungary

On March 19, 1944, German soldiers invaded Hungary. With them came a special unit led by Adolf Eichmann. Eichmann was in charge of Jewish affairs for the Germans. His arrival in Budapest meant the Germans planned to deal with Hungary's Jewish population. Hungary had about 725,000 Jewish people.

Before the invasion, Hungary already had laws against Jews. For example, they couldn't marry Christians. After the invasion, the Hungarian government started separating Jews from others. From April 5, 1944, Jews over six years old had to wear a yellow star. They were not allowed to use telephones, own cars or radios, or travel. Jewish people lost their jobs, and their property was taken.

Meeting with German Officers

After the invasion, Kasztner and other committee members hid. They wanted to talk to the Germans. They paid $20,000 to arrange a meeting with Dieter Wisliceny, one of Eichmann's assistants.

Other Jewish groups had tried to bribe German officers before. In Slovakia, a group called the Working Group paid Wisliceny about $50,000 in 1942. They hoped this would stop Jews from being sent to Poland. The deportations did stop for a while, and the Working Group thought their bribe worked. But it was actually stopped for other reasons.

The Aid and Rescue Committee decided to ask Wisliceny if the Germans would "negotiate on an economic basis" to ease the anti-Jewish rules. Joel Brand and Kasztner met Wisliceny on April 5, 1944. They offered $2 million, with $200,000 paid upfront. They asked for no deportations, no killings, no ghettos, and that Jews with papers to go to Palestine could leave. Wisliceny took the $200,000. He said there would be no deportations while talks continued. He also gave the committee special passes to travel and use cars and phones.

First Meeting with Eichmann

After talking to Wisliceny, Joel Brand received a message on April 25: Eichmann wanted to see him. Brand was driven by the SS to Eichmann's office at the Hotel Majestic. Another German officer, Kurt Becher, was also there. Brand later wrote that Eichmann wore a "well-cut" uniform. He remembered Eichmann's "steely blue, hard and sharp" eyes.

Eichmann said he would talk to his superiors in Berlin. In the meantime, Brand should decide what goods he could offer. When Brand asked how his committee would get these goods, Eichmann suggested Brand talk to the Allies overseas. Eichmann said he would arrange travel papers. Brand suggested he would go to Istanbul, Turkey, because another committee member had a contact there. Brand later said he felt like a "madman" after leaving the hotel.

More Meetings and the Deal

A few days later, Eichmann called Brand again. This time, Gerhard Clages, a security chief for Himmler, was with Eichmann. Clages gave Brand $50,000 and 270,000 Swiss francs. This money had been sent to the Aid and Rescue Committee but was taken by the Germans.

Eichmann told Brand he wanted 10,000 new trucks for the German army to use on the Eastern front. He also wanted 200 tons of tea, 800 tons of coffee, 2 million cases of soap, and other materials like tungsten. Eichmann said if Brand came back from Istanbul with proof that the Allies agreed, he would release 10 percent of the one million Jews. The deal would be 100,000 Jews for every 1,000 trucks.

The Deal Falls Apart

Mass Killings Begin

It's not clear if Eichmann gave Brand a deadline to return to Budapest. Joel Brand said at different times that he had one, two, or three weeks. Hansi Brand later said that she and her children had to stay in Budapest as hostages. Brand and Eichmann met for the last time on May 15. This was the same day that large-scale deportations to Auschwitz began. Between May 15 and July 9, 1944, about 437,000 Jewish people from the Hungarian countryside were sent to Auschwitz on 147 trains. Most were killed in gas chambers when they arrived.

Brand Travels to Istanbul

Brand got a letter of recommendation for the Jewish Agency from the Hungarian Jewish Council. He was told he would travel with Bandi Grosz, a Hungarian who worked for German intelligence. The SS drove them from Budapest to Vienna on May 17. Grosz later said that Brand's mission was a cover for his own. Grosz was supposed to arrange a meeting in a neutral country between German and American or British officers to discuss peace.

In Vienna, Brand was given a German passport with the name Eugen Band. He sent a message to the Jewish Agency in Istanbul saying he was coming. He arrived by German diplomatic plane on May 19. Paul Rose writes that Brand didn't know at this point that the deportations to Auschwitz had already started.

Brand had been told that "Chaim" would meet him in Istanbul. He thought this was Chaim Weizmann, a very important Zionist leader. But it was actually Chaim Barlas, another Jewish Agency leader. Also, there was no entry visa waiting for Brand, and he was almost arrested. Brand felt this was the first time the Jewish Agency let him down.

The visa problem was fixed, and Brand met the Jewish Agency delegates. Brand was angry that no one important enough was there to make a deal. The Jewish Agency agreed to have Moshe Sharett, another important leader, come to Istanbul to meet him. Brand gave them a map of Auschwitz and asked them to bomb the gas chambers, crematories, and railway lines. He felt very discouraged after these talks. He wrote that the delegates didn't seem to understand how urgent the situation was. They were more focused on politics and Jewish emigration to Palestine than on the killings in Europe.

Temporary Agreement and British Arrest

Ladislaus Löb writes that many ideas were sent between Istanbul, London, and Washington. The Jewish Agency and Brand wanted the Allies to pretend to go along with the Germans. This was to hopefully slow down the deportations. The Agency gave Brand a document on May 29, 1944. It offered money for Jewish people to go to Palestine or neutral countries. It also offered monthly payments if the deportations stopped. If the Germans allowed food and medicine for Jews in camps, the Allies would supply the same to the Nazis. This agreement was just to give Brand something to take back to Budapest.

Brand sent messages to his wife on May 29 and 31 to tell her (and Eichmann) about the agreement. But there was no reply. Rezső Kasztner and Hansi Brand had been held in Budapest by the Hungarian Arrow Cross. They got the messages when they were released, but Eichmann refused to stop the deportations.

In Istanbul, Brand was told that Moshe Sharett couldn't get a visa for Turkey. The Jewish Agency asked Brand to meet Sharett in Aleppo, on the Syrian-Turkish border. Brand didn't want to go because the area was under British control, and he feared they would question him. But the Agency told him it would be safe.

As soon as he arrived at the Aleppo train station on June 7, a British man stopped him. He was pushed into a waiting Jeep. The British took him to a house. For four days, they tried to stop Moshe Sharett from meeting him. Sharett fought hard, and on June 11, he finally met Brand. The discussion lasted several hours. Sharett wrote later: "I must have looked a little incredulous, for he said: 'Please believe me: they have killed six million Jews; there are only two million left alive.'" At the end of the meeting, Sharett told Brand that the British insisted he not return to Budapest. Brand became very upset.

The Proposal is Rejected

Brand was taken to Cairo, Egypt, where the British questioned him for weeks. On June 22, 1944, he was interviewed by Ira Hirschmann from the American War Refugee Board. Hirschmann wrote a good report about Brand, but it didn't have much effect. Brand went on a hunger strike for 17 days to protest being held.

The British, Americans, and Soviets talked about the proposal. British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden wrote a memo on June 26 about the choices. The British believed it was a trick by Himmler. They thought Grosz was a spy, and that Brand's mission was a "smokescreen" for the Germans to make a peace deal without the Soviet Union. If the deal happened and many Jews were released, Allied military operations might have to stop. Historians believe the British feared Himmler wanted to use the Jews as human shields. This would allow the Germans to focus on fighting the Soviet army.

The Americans were more open to talking. But a disagreement grew between them and the British. The British were worried about many Jewish people moving to Palestine, which they controlled at the time. On July 1, Eden suggested a very small counter-proposal. He told the American government that the British would let Brand return to Budapest with a message for Eichmann. This message would suggest that 1,500 Jewish children go safely to Switzerland. Also, 5,000 Jews from Bulgaria and Romania could go to Palestine. Germany would also guarantee safe passage for ships carrying Jewish refugees. He didn't say what he would offer in return.

On July 11, Prime Minister Winston Churchill ended the idea. He told Eden that the murder of the Jews was "probably the greatest and most horrible crime ever committed." He said there should be "no negotiations of any kind on this subject." He didn't take Brand's mission seriously. On July 13, the Cabinet Committee on Refugees decided to "totally ignore the combined Brandt–Gestapo approach."

News Leaks to the Public

The British shared details of Eichmann's proposal with the news media. On July 19, 1944, the New York Herald Tribune reported that two Hungarian government messengers in Turkey had offered to exchange Hungarian Jews for British and American medicines and transport for the Germans. On July 20, The Times newspaper called it "one of the most loathsome" stories of the war. They said it was an attempt to "blackmail, deceive and split" the Allies.

The mass deportations of Hungarian Jews had already stopped by the time the news leaked. After parts of the Vrba-Wetzler report were published in mid-June, which described the gas chambers in Auschwitz, the Jewish Agency asked London to hold Hungarian ministers responsible for the killings. This message was seen by Hungarian regent Miklós Horthy. On July 7, 1944, he ordered an end to the deportations. The British released Brand on October 5, 1944. Brand said they wouldn't let him return to Hungary and made him go to Palestine. However, some historians believe Brand was simply afraid to go back to Budapest, fearing the Germans would kill him.

Himmler's Role

Germany's Foreign Minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, apparently knew nothing about the proposal. He asked about it and was told on July 22 that Brand and Grosz had been sent to Turkey by order of Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS. Eichmann himself said after the war that the order came from Himmler. SS officer Kurt Becher also said: "Himmler said to me: 'Take whatever you can from the Jews. Promise them whatever you want. What we will keep is another matter.'"

Historians find the way the Germans handled this deal very strange. Some believe Eichmann wanted to kill Jews, not sell them. But he was forced to act as Himmler's messenger. On the day Brand left Germany for Istanbul in May 1944, Eichmann was in Auschwitz. He was checking that it was ready for the trains of Jews coming from Hungary. This doesn't suggest he was going to stop the killings.

Some historians think Himmler was interested in secret peace talks. Brand and Grosz arrived in Istanbul just two months before the attempt to kill Adolf Hitler on July 20, 1944. Himmler knew that attempts might be made on Hitler's life. He may have wanted to make a peace deal in case Hitler died. He would use low-level agents so he could deny knowing about it if Hitler survived. Brand himself later believed the proposal was meant to create problems between the Allies.

The Kasztner Train

Joel Brand not returning to Budapest was a big problem for the Aid and Rescue Committee. On May 27, Hansi Brand was arrested and beaten by the Hungarian Arrow Cross. Kasztner wrote that on June 9, Eichmann told him: "If I do not receive a positive reply within three days, I shall operate the mill at Auschwitz." Eichmann later denied saying this.

Historians say the Aid and Rescue Committee made a mistake. They believed Jewish leaders could easily travel and convince the Allies to act. They also thought American Jews had easy access to money and goods. The committee trusted the Allies, but the Allies were preparing for the invasion of Normandy, which began on June 6, 1944. At that time, upsetting the Soviets over a German plan to ransom Jews was impossible.

Despite these problems, Kasztner, Hansi Brand, and the committee managed to save about 1,684 Jewish people. This included 273 children. They were allowed to leave Budapest for Switzerland by train on June 30, 1944. The committee paid SS officer Kurt Becher $1,000 per person in money, jewelry, and gold. This money came from the wealthier passengers. After a detour to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, the passengers arrived in Switzerland in two groups later that year. Joel Brand's mother, sister, and niece were on this train.

Later Life and Legacy

Moving to Israel

Historians believe Joel Brand was a very brave man who wanted to help Jewish people. But after his mission, he faced suspicion, even from other members of the Aid and Rescue Committee. This was because he didn't return to Budapest. After the British released him, he joined the Stern Gang. This group was fighting to remove the British from Palestine. Joel and Hansi Brand lived the rest of their lives in Israel, first on a kibbutz, then in Tel Aviv, with their two sons.

Giving Testimony

Brand spoke about the "blood-for-goods" proposal in several trials. In 1954, he testified in a trial in Jerusalem involving Rezső Kasztner. Kasztner was sued by the Israeli government because a Holocaust survivor named Malchiel Gruenwald accused him of working with the Nazis. Brand testified for Kasztner. But instead of defending him, Brand used the chance to accuse the Jewish Agency of helping the British stop the "blood-for-goods" proposal.

The judge in that trial said Kasztner had "sold his soul to the devil" by negotiating with Eichmann. The judge also said Kasztner didn't do enough to warn people that they were being sent to gas chambers. The Supreme Court of Israel later overturned most of this verdict. But Kasztner was killed in 1957 because of the earlier judgment.

Joel and Hansi Brand both testified in 1961 during the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. Eichmann said he chose Brand because he seemed like an "honest, idealistic man." In May 1964, Brand testified in Germany against two of Eichmann's assistants.

Death

Joel Brand died of a heart attack in July 1964, at age 58, while visiting Germany. He told an interviewer shortly before his death: "An accident of life placed the fate of one million human beings on my shoulders. I eat and sleep and think only of them." More than 800 people attended his funeral in Tel Aviv. Important figures like Teddy Kollek, director-general of the prime minister's office, were there. The speech at his funeral was given by Gideon Hausner, the lawyer who prosecuted Adolf Eichmann.

See also

In Spanish: Joel Brand para niños

In Spanish: Joel Brand para niños