Sobibor extermination camp facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sobibor |

|

|---|---|

| Extermination camp | |

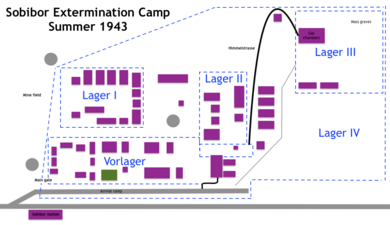

Sobibor extermination camp, summer 1943

|

|

| Coordinates | 51°26′50″N 23°35′37″E / 51.44722°N 23.59361°E |

| Other names | SS-Sonderkommando Sobibor |

| Known for | Genocide during the Holocaust |

| Location | Near Sobibór, General Government (occupied Poland) |

| Built by |

|

| Commandant |

|

| Operational | May 1942 – 14 October 1943 |

| Inmates | Jews, mainly from Poland |

| Number of inmates | 600–650 slave labour at any given time |

| Killed | 170,000–250,000 |

| Notable inmates | List of survivors of Sobibor |

Sobibor was a Nazi death camp built and run by Nazi Germany. It was part of a terrible plan called Operation Reinhard. The camp was hidden in a forest near the village of Żłobek Duży in German-occupied Poland.

Sobibor was not like a regular prison camp. Its only goal was to murder Jewish people. Between 170,000 and 250,000 people were killed there. This made Sobibor one of the deadliest Nazi camps. Only Auschwitz, Treblinka, and Belzec had more victims.

The camp stopped working after a brave revolt by the prisoners. This happened on October 14, 1943. The prisoners planned to secretly kill the SS officers first. Then, all 600 prisoners would walk out the front gate. But the plan changed after only eleven SS men were killed. The prisoners had to escape by climbing over barbed wire fences. They also ran through a minefield while being shot at. About 300 prisoners got out of the camp. Around 60 of them survived the war.

After the revolt, the Nazis destroyed most of the camp. They wanted to hide their terrible crimes from the approaching Red Army. For many years after World War II, the site was not well known. It became more famous after being shown in the TV show Holocaust (1978) and the movie Escape from Sobibor (1987). Today, the Sobibor Museum stands at the site. Experts called archaeologists are still studying the area. In 2020, photos of the camp were published. These photos were part of the Sobibor perpetrator album.

Why Sobibor Was Built

Operation Reinhard's Purpose

Sobibor was one of four death camps built for Operation Reinhard. This was the deadliest part of the Holocaust. The Nazis did not decide to kill all Jewish people at once. Instead, they made separate plans for different areas they controlled. After invading Poland in 1939, the Germans started moving Jewish people. They sent them from ghettos to forced labor camps. These camps were in a harsh area called the Lublin District.

In 1941, the Nazis began trying out ways to kill people using gas. In December 1941, they used gas vans at Chełmno. The first large-scale gassings happened at Auschwitz concentration camp in January 1942. On January 20, 1942, a Nazi leader named Reinhard Heydrich announced a plan. It was to systematically murder Jewish people using a network of death camps. This plan became known as Operation Reinhard.

No one knows for sure when the planning for Sobibor began. Some historians think it started as early as 1940. This is based on an old railway map. It showed Sobibór and Bełżec but left out bigger cities. The first real proof of Nazi interest in the site came in late 1941. Local Polish people saw SS officers surveying the land near the train station.

Building the Camp

In March 1942, SS officer Richard Thomalla took over building Sobibor. Construction had started earlier, but the exact date is unknown. Thomalla had built the Bełżec death camp before. He used what he learned to make Sobibor even bigger. This allowed more space for all the camp's buildings inside its fences.

The camp used some buildings that were already there. These included a post office and a forester's lodge. The forester's lodge became the main office. The post office was used for SS officers to live in. This old post office building is still standing today. The SS also added a special train track. It went 800 meters inside the camp. This allowed regular trains to keep running while new prisoners arrived.

The first workers who built the camp were mostly locals. It's not clear if they were Polish or Jewish forced laborers. Later, the Jewish council in nearby Włodawa was ordered to send 150 Jewish people to help build. These workers were treated very badly. They were killed if they looked tired. Most were murdered when the camp was finished. But two escaped and tried to warn the Jewish council. Their warnings were not believed.

The first gas chambers at Sobibor were like those at Belzec. But they did not have furnaces. To make the gas, an SS officer got a heavy gasoline engine from a military vehicle. He set up the engine at Sobibor. He connected its exhaust pipes to the gas chamber. In April 1942, the Nazis tested the gas chambers. They murdered thirty to forty Jewish women from a labor camp.

The main building of Sobibor was finished by summer 1942. After that, many prisoners started arriving. But the SS kept making the camp bigger and better. The first gas chambers were torn down in summer 1942. New, larger ones made of brick were built. Later that summer, the SS also tried to make the camp look nicer. They cleaned the buildings more often. They also made the front area, called the Vorlager, look like a "Tyrolean village." This was meant to trick new prisoners.

How the Camp Was Organized

Sobibor was surrounded by two barbed wire fences. Pine branches were woven into the fences to block the view inside. The camp had two gates at one corner. One was for trains, and the other for people and cars. The camp was split into five areas: the Vorlager (front camp) and four Lagers (camps) numbered I to IV.

The Vorlager had living and recreation buildings for the camp staff. SS officers lived in cottages with names like "The Merry Flea." They had a canteen, a bowling alley, and a barber. Jewish prisoners were forced to work in these places. The guards, who were Soviet prisoners of war, had their own separate barracks and recreation areas.

The Nazis made the Vorlager look very nice. It had lawns, gardens, and neat paths. This pretty look helped hide the camp's true purpose. Prisoners arriving by train would see this area first. One survivor remembered feeling relieved by the "Tyrolean cottage-like barracks."

Lager I had barracks and workshops for the prisoners. These included shops for tailors, carpenters, and mechanics. It also had a bakery. This area was hard to escape from. It had a water-filled trench on one side.

Lager II was a larger area with many uses. One part, called the "Erbhof", had the main office and a small farm. The farm raised chickens, pigs, and vegetables for the SS officers. Lager II also had buildings where new arrivals were prepared before being murdered. This included sorting barracks. Here, items stolen from victims were stored. There was also a yard where new arrivals had to undress. This yard was decorated with flowers to hide the camp's purpose. From this yard, a narrow path led to the gas chambers in Lager III. This path was called the Himmelstrasse (road to heaven) or the Schlauch (tube). It was covered on both sides by fences with pine branches.

Lager III was the killing area. It was separate from the rest of the camp. It was in a forest clearing and had its own fence. Prisoners from Lager I were not allowed near it. They were killed if they were thought to have seen inside. Not much is known about Lager III. We know it had gas chambers and mass graves. It also had special housing for the Sonderkommando prisoners. These prisoners were forced to work there.

Lager IV was added in July 1943. It was still being built when the revolt happened. This area was in a heavily wooded part of the camp. It was meant to be a storage place for weapons taken from Soviet soldiers.

Life for Prisoners

Sobibor was a death camp. This means that only about 600 slave laborers lived there. They were forced to help run the camp. At Sobibor, being "selected" meant being chosen to live, even if only for a short time. Most new prisoners died within a few months because of the terrible conditions.

Daily Work

Prisoners worked from 6:00 am to 6:00 pm. They had a short break for lunch. Sundays were supposed to be half days, but this did not always happen. Many prisoners had special skills. They were goldsmiths, painters, gardeners, or tailors. These skilled workers were officially kept alive to help the camp. But much of their work was used by SS officers for their own gain. For example, a famous painter was forced to paint pictures for the SS. A goldsmith had to make jewelry from gold teeth taken from victims. Skilled prisoners were seen as very valuable. They got better treatment than others.

Other prisoners did different jobs. Many worked in Lager II sorting barracks. They had to go through luggage left by victims. They repackaged valuable items as "charity gifts" for German civilians. These workers sometimes got to eat food found in the luggage. Younger prisoners often worked as "putzers." They cleaned for the Nazis and guards and helped them.

In Lager III, a special group of Jewish prisoners was forced to help with the killing process. These prisoners saw the murders directly. They were kept completely separate from other prisoners. The SS would regularly kill these workers. This was because of the hard work and mental stress. No workers from Lager III survived. So, we don't know much about their lives.

When Lager IV was being built, a "forest commando" was formed. These prisoners cut wood for heating, cooking, and burning bodies.

Social Connections

It was hard for prisoners to make friends. This was because people were constantly dying or being moved. Also, there was a lot of distrust. People from different countries or who spoke different languages often didn't trust each other. Dutch Jews were often looked down on. German Jews also faced suspicion. People thought they might side with their captors. When groups did form, they were usually based on family or shared nationality. These groups were very closed off. Some prisoners from Western Europe were not told important things about the camp.

Because they expected to die soon, prisoners lived one day at a time. Crying was rare. Evenings were often spent trying to enjoy what little life they had left. Prisoners sang and danced. Romantic relationships were common. Some of these were forced, but others were real connections. Two couples who met in Sobibor got married after the war. The Nazis even encouraged this cheerful atmosphere. They forced prisoners to join a choir. Many prisoners thought the Nazis did this to keep them calm and stop them from planning escapes.

Prisoners had a social order. It was based on how useful they were to the Germans. There were three groups:

- "Drones" who were easily killed.

- Privileged workers who had special jobs and some comforts.

- Artisans whose skills made them very important. They got the best treatment.

The Nazis also appointed "kapos." These were prisoners forced to supervise other prisoners. Kapos used whips to enforce orders. Kapos were forced into their roles. They reacted differently to the pressure. Some were very cruel. One Oberkapo (head kapo) was nicknamed "Mad Moisz." He would beat prisoners badly, then apologize. Another Oberkapo was named Herbert Naftaniel. He was known for his cruelty. He was eventually beaten to death by prisoners with permission from an SS officer.

Despite these divisions, prisoners found ways to help each other. Sick or hurt prisoners secretly got food and medicine. Healthy prisoners covered for sick ones. If a prisoner couldn't work, they would be killed. The camp nurse found a way to fake records. This allowed sick prisoners to rest for more than three days. Members of the railway brigade tried to warn new arrivals about their fate. But they were often not believed. The most successful act of helping each other was the revolt. It was planned so that all prisoners had a chance to escape.

Health and Living Conditions

Prisoners suffered from not enough sleep, hunger, and hard work. They were also constantly beaten. Lice, skin infections, and breathing problems were common. Typhoid fever sometimes spread through the camp. When Sobibor first opened, sick or hurt prisoners were shot right away. Later, the SS worried that too many deaths made the camp less efficient. They changed the rule. Prisoners could have three days to recover. If they still couldn't work after three days, they were killed.

Food was very scarce. Prisoners got about 200 grams of bread for breakfast. They also got a coffee substitute. Lunch was usually a thin soup, sometimes with potatoes or horse meat. Dinner was often just coffee again. Prisoners on these rations felt their personalities change due to hunger. Some secretly got more food. They took it from victims' luggage while working. A system of trading developed in the camp. Prisoners and guards traded items. Guards would trade jewels and cash from the sorting barracks for food and alcohol from local farmers.

Most prisoners had little or no way to stay clean. There were no showers in Lager I. Clean water was hard to find. Clothes could be washed or replaced from the sorting barracks. But the camp was so full of bugs that it didn't help much. Some prisoners who worked in the laundry had better access to hygiene.

Camp Personnel

Sobibor was run by a small group of German and Austrian SS officers. There was also a much larger group of guards, mostly from the Soviet Union.

SS Officers

Sobibor had about 18 to 22 German and Austrian SS officers. Most of them came from working-class backgrounds. They had been merchants, farmers, or police officers. Almost all of them had worked in a Nazi program called Aktion T4. This program killed people with disabilities. Many of the cruel practices from that program continued at Sobibor. About 100 SS officers worked at Sobibor over time.

When Sobibor opened, its first commander was Franz Stangl. He was very organized and worked to make the killing process more efficient. Stangl didn't interact much with prisoners. But one survivor remembered him as a vain man who seemed to enjoy his work. Stangl was moved to Treblinka in August 1942. Franz Reichleitner took his place. Reichleitner was very anti-Jewish. He didn't care about anything in the camp except the killing. Johann Niemann was the camp's second-in-command.

The daily operations were usually handled by Gustav Wagner. He was the most feared man in Sobibor. Prisoners called him "The Beast" and "Wolf." He was seen as brutal and unpredictable. Karl Frenzel was in charge of Lager I and acted as the camp's "judge." Kurt Bolender and Hubert Gomerski oversaw Lager III, the killing area. Erich Bauer and Josef Vallaster usually directed the gassing itself.

The SS men liked their jobs. They had comforts not available to soldiers fighting in the war. Their area had a canteen, bowling alley, and barber shop. They also got paid well. They received extra money for killing Jews. They also made a lot of money by stealing from their victims. For example, they forced a 15-year-old goldsmith to make them jewelry from gold teeth.

After the war, SS officers claimed they would have been killed if they didn't participate. But judges found no proof of SS officers being executed for refusing. At least one Sobibor officer successfully got transferred out.

Watchmen

Sobibor was guarded by about 400 "watchmen." Survivors often called them "blackies" or "Ukrainians." Many were captured Soviet soldiers. They volunteered to work for the SS to escape terrible conditions in Nazi prison camps. Watchmen were guards. But they also supervised work and carried out punishments and executions. They helped with the killing process. They unloaded prisoners from trains and led them to the gas chambers. Watchmen wore mixed uniforms, often dyed black. They received pay and food similar to SS soldiers.

The watchmen scared the prisoners. But they were not always loyal to the SS. They were part of a secret trading system in the camp. They also drank a lot, even though it was forbidden. The SS officers didn't fully trust the watchmen. They limited their access to weapons. Watchmen were often moved between different camps. This was to stop them from making local friends or learning about the area. After the prisoner uprising, the SS feared the watchmen would revolt. They sent them back to Trawniki under armed guard. Their fears were right. The watchmen killed their SS escorts and ran away.

Interactions Between Prisoners and Perpetrators

Prisoners lived in constant fear of their captors. They were punished for small things. This included smoking, resting, or not showing enough enthusiasm when forced to sing. Punishment was used to enforce rules and the guards' personal wishes. The most common punishment was whipping. SS officers carried special whips made by prisoners from victims' leather. Many survivors remember a large, aggressive dog named Barry. SS officers would set Barry on prisoners. In summer 1943, two SS officers formed a "penal brigade." Prisoners in this group were forced to work while running. Most died within three days.

The SS had total power over the prisoners. They treated them as entertainment. They forced prisoners to sing while working, marching, and even during executions. Some survivors said prisoners were forced to do mock "cockfights" for the SS. Others had to sing insulting songs.

One SS officer, Johann Klier, was known to be more humane. Several survivors spoke for him at his trial. One survivor said, "I don't even know why he was in Sobibor... even the other Nazis picked on him."

Prisoners thought the watchmen were the most dangerous staff. Their cruelty was worse than the SS officers. But some watchmen were kind to Jewish prisoners. They did the least they could while on duty. Some even helped prisoners try to escape. In one case, two watchmen escaped with six Jewish prisoners. But they were betrayed and killed.

The Killings at Sobibor

How Many Died?

Between 170,000 and 250,000 Jewish people were murdered at Sobibor. The exact number is not known. This is because no full records survived. The number 250,000 was first suggested in 1947 by a Polish judge. He interviewed survivors and railway workers to guess how many trains arrived. Later research has found similar numbers using other documents. But some recent studies suggest lower numbers, like 170,165. One historian said, "The range of scientific research into this question shows how little we currently know about the number of victims of this extermination camp."

One important source is the Höfle Telegram. This was a collection of SS messages. It gave exact numbers of "recorded arrivals" at each death camp up to December 31, 1942. Another Nazi document, the Korherr Report, has the same numbers. Both say 101,370 people arrived at Sobibor in 1942. But what this number means is debated. Some experts think it only counts Jews from within Poland. Others think it's the total for that year.

Other information comes from records of specific trains sent to Sobibor. For example, a Dutch archive has exact records of 34,313 people sent from the Netherlands. In other cases, trains are only known through small clues.

It's hard to get an exact number because records are incomplete. Records of people sent by train are more likely to exist. This means estimates might miss people brought by trucks or on foot. Even train records seem to have gaps. For example, a letter mentions trains from Warsaw to Sobibor, but no schedules exist. On the other hand, some estimates might count people as Sobibor victims who died elsewhere. Or they might have even survived. This happened when small groups were chosen to work in nearby labor camps.

Other numbers have been given that are different from what history shows. Some reports right after the war said as many as 3 million died. During the Sobibor trials in the 1960s, judges used a number of 152,000 victims. But they said this was a minimum number. Survivors have suggested much higher numbers. Many remember a camp rumor that a Nazi leader's visit in 1943 was to celebrate the millionth victim. One perpetrator even said his colleagues regretted that Sobibor only killed 350,000.

The Uprising

On the afternoon of October 14, 1943, prisoners in Sobibor secretly killed eleven SS men. Then, about 300 prisoners escaped to freedom. This was one of only three uprisings by Jewish prisoners in death camps. The others were at Treblinka extermination camp and Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Leading Up to the Revolt

In summer 1943, rumors spread that Sobibor would soon close. Prisoners knew this meant they would all be killed. This was because the last prisoners from the Bełżec death camp had been murdered at Sobibor. The Bełżec prisoners had sewn messages into their clothes:

We worked at Bełżec for one year and did not know where we would be sent next. They said it would be Germany... Now we are in Sobibór and know what to expect. Be aware that you will be killed also! Avenge us!

A group of prisoners formed an escape committee. Their leader was Leon Feldhendler. He had been a Jewish community leader. His job in the sorting barracks gave him extra food. This helped him stay mentally sharp. But the committee didn't make much progress. They had to keep their plans secret, so only a few Polish Jews were involved. None of them had military experience to plan a mass escape. By late September, they were stuck.

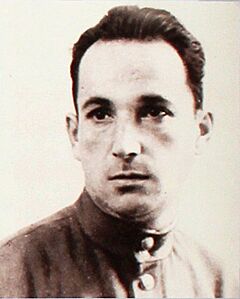

On September 22, the situation changed. About twenty Jewish Soviet soldiers, who were prisoners of war, arrived. They came from the Minsk Ghetto and were chosen for labor. One of them was Alexander Pechersky. He was an actor and a military leader. He would become the main leader of the revolt. The escape committee was excited but also careful about these new arrivals. The Russians were soldiers and had the skills needed for an escape. But it wasn't clear if they could be trusted.

Feldhendler introduced himself to Pechersky using a fake name. He watched Pechersky for a few days. Pechersky stood out because he stood up to the SS officers. But he did so carefully. Feldhendler invited Pechersky to share news from outside the camp. This meeting was in the women's barracks. Feldhendler was surprised Pechersky spoke little Yiddish. But they could talk in Russian. Pechersky agreed to come. At the meeting, Pechersky gave a speech. His friend translated into Yiddish. Feldhendler and the committee were worried about Pechersky's communist ideas. But they were impressed by him. They were especially struck when Pechersky said, "No one can do our work for us."

Over the next few weeks, Pechersky met often with the escape committee. These meetings happened in the women's barracks. They pretended he was visiting a woman named "Luka." Pechersky and Feldhendler agreed that the revolt would give all 600 prisoners a chance to escape. But they later decided they couldn't include the 50-plus sonderkommando workers. These workers were kept completely separate in Lager III. At first, Pechersky and his friend thought about digging a tunnel. It would go from the carpenter's workshop in Lager I. But this idea was too hard. The tunnel might flood or hit a mine. Also, they doubted they could get all 600 prisoners through it without being caught.

The final idea for the revolt came to Pechersky while he was cutting wood. He was near Lager III. He heard a child screaming "Mama! Mama!" in the gas chamber. He felt helpless. This reminded him of his own daughter. He decided the plan couldn't just be an escape. It had to be a revolt. Over the next week, Pechersky and his friend developed the final plan.

The Revolt Begins

The revolt started late in the afternoon on October 14, 1943. The plan had two parts. First, prisoners would trick SS officers into going to quiet places. Then, they would kill them. These secret killings would happen in the hour before the evening roll call. The second part would start at roll call. All prisoners would gather in the Lager I yard. The kapos would announce a special work detail outside the camp. The whole group would calmly march out the front gate. If the guards found this strange, they wouldn't be able to check or react. This was because the SS men would be dead.

Secret Killings

At 4:00 pm, Deputy Commandant Johann Niemann rode to the tailor's barracks. The head tailor had made an appointment with him for a leather jacket fitting. The plotters wanted to kill Niemann first. He was acting commander while the main commander was away. They thought Niemann's death alone would cause enough confusion for some to escape. The tailor asked Niemann to take off his gun holster and try on the jacket. The tailor then asked Niemann to turn around. He pretended to check the back of the jacket. When Niemann turned, two prisoners killed him.

Over the next hour, an SS officer was killed about every six minutes. Besides Niemann, others killed in Lager I included Josef Vallaster and Siegfried Graetschus. In Lager II, Josef Wolf and Rudolf Beckmann were killed. Walter Ryba was killed in the Vorlager. Many details of these killings are not known.

The plotters had planned to kill Rudolf Beckmann in a storage barracks. But Beckmann suddenly turned back to the main office. Chaim Engel volunteered to kill Beckmann in his office. Engel and another prisoner went to the office. Engel killed Beckmann.

While the killings happened, Szlomo Szmajzner went to get more guns. He went to the watchmen's barracks in the Vorlager. As the camp machinist, he often went there to fix stoves. He carried a stovepipe over his shoulder. He took six rifles and ammunition. He could only fit two rifles inside the pipe. He wrapped the others in a blanket. He decided to stay hidden until the bugle call. This way, if caught, it would look like he acted alone. Just before the 5:00 pm bugle, he found two child prisoners. He told them to carry the blanket with the rifles. After the bugle, he gave the rifles to the Russian prisoners. But he insisted on keeping one for himself.

The Breakout

As roll call got closer, Pechersky worried the revolt would be found out. He thought about starting the escape early. But he didn't want to while Karl Frenzel was still alive. Frenzel was one of the most dangerous officers. He was taking a shower and was late for his appointment. Close to 5:00 pm, Pechersky and his friend decided to give up on Frenzel. They sent the bugler to blow the bugle. This signaled the end of the workday.

Many prisoners in Lager I had already left their jobs. They were standing in the roll call yard or hiding. In Lager II, prisoners were confused by the early bugle. They gathered in a messy way to march back to Lager I. Feldhendler worried their messy line would attract guards' attention. So he decided to lead the march himself. He lined them up. They marched, singing a German song. As prisoners gathered, rumors of the revolt spread. When a guard told them to line up faster, prisoners shouted, "Don't you know the war is over?" They then killed him in the open. Many others were shocked. Pechersky realized the yard was dangerous. He tried to tell the group what was happening. A survivor remembered Pechersky's speech:

Our day has come. Most of the Germans are dead. Let's die with honor. Remember, if anyone survives, he must tell the world what has happened here!

As prisoners started to scatter, they heard shots from Lager II. These shots were fired by Erich Bauer. He had just returned with a truck full of alcohol. Just before the bugle, Bauer had told two child prisoners to unload the alcohol. They were to carry it into the office where Beckmann had been killed. Around the time Pechersky was speaking, a guard ran to Bauer shouting, "A German is dead!" Bauer thought the children were responsible. He killed one child but missed the other. When prisoners in Lager I heard the shots, they ran in every direction. A group pulled a guard off his bicycle and killed him. Many prisoners had to decide quickly without knowing exactly what was happening. The plan was kept secret. Even those who knew about the revolt knew few details. Pechersky and Feldhendler ran around the yard. They tried to guide prisoners out. But about 175 prisoners stayed behind.

As the crowd rushed forward, the guards in the towers were confused. They didn't react at first. One survivor saw some SS men hiding. They might have thought the camp was being attacked by resistance fighters. After a moment, the guards started shooting into the crowd. Some prisoners shot back with the rifles Szmajzner had gotten.

One group of prisoners ran behind the carpenter's shop. The carpenters had left ladders, pliers, and axes there. This was a backup plan if the main gate was blocked. These prisoners climbed the fence, crossed a ditch, and ran through the minefield towards the forest. As they ran, mines exploded. Some escapees were killed. This drew the attention of the guards, who started shooting.

A larger group of prisoners headed for the Vorlager. They tried to escape through the main gate or over the south fence. A group of Soviet prisoners tried to raid the weapons storage. There, they met Frenzel. He had just gotten out of the shower. He was getting a drink in the canteen. He heard the noise. Frenzel grabbed a machine gun and ran outside. He saw the crowd heading to the main gate and opened fire. Pechersky shot at Frenzel but missed. A group of prisoners tried to rush the main gate. But another SS officer was there, shooting into the crowd. Some scattered. But others were pushed forward by the crowd behind them. They broke through the main gate and flooded out.

Others in the Vorlager tried to escape over the barbed wire behind the SS barracks. They guessed there would be fewer mines there. Many prisoners got stuck on the barbed wire. One survivor, Thomas Blatt, survived because the fence fell on him. As he lay there, he saw prisoners in front of him blown up by mines. Blatt freed himself by slipping out of his coat. He ran across the exploded mines and into the forest.

About 300 prisoners escaped to the forest.

After the Escape

Right after the escape, in the forest, about fifty prisoners followed Pechersky. After a few days, Pechersky and seven other Russian soldiers left. They said they would return with food. But they left to cross a river and meet with resistance fighters. When Pechersky didn't come back, the remaining prisoners split into smaller groups. They tried to find their own ways to survive.

In 1980, a survivor asked Pechersky why he left the others. Pechersky replied that his job was done. He said the Polish Jews were in their own land. He was a Soviet soldier. He believed survival chances were better in smaller groups. He felt he couldn't tell them directly to split up. He said, "We were only people. The basic instincts came into play. It was still a fight for survival."

A Dutch historian and Sobibor survivor estimated that 158 prisoners died during the revolt. They were killed by guards or in the minefield. Another 107 were killed by SS, German soldiers, or police who chased them. About 53 escaped prisoners died from other causes before the war ended. There were 58 known survivors. They were slave laborers who worked daily in Sobibor. Their time in the camp ranged from a few weeks to almost two years.

Closing and Destroying the Camp

Once the shooting stopped, the remaining SS officers secured the camp. They killed those found hiding. They searched for Niemann, who was in charge. After dark, the search continued. Prisoners had cut the power lines.

Around 8:00 pm, Niemann was found. Frenzel took command. His first step was to call for more soldiers. He worried the remaining prisoners would fight back. He also worried the escapees might attack again. He found the phone lines cut. So he went to the Sobibór train station, just outside the camp. He called SS offices in Lublin and Chełm. He also called a nearby German army unit. Reinforcements were delayed. This was due to confusion and railway lines being blown up by Polish resistance fighters. But some SS officials arrived later that night. One ordered Erich Bauer to go get police in person. Bauer was scared he would be attacked.

During the night, the SS searched the camp for hiding prisoners. Many were armed and fought back. One survivor saw this search before escaping. He heard shouts and screams. He heard Germans say, "Nobody is here." He climbed a watchtower and jumped over the fences and mines. He escaped to the forest.

Early the next day, October 15, more SS and German soldiers arrived. They marched the remaining 159 prisoners to Lager III and shot them. The Nazis started a huge search for the escapees. They worried the advancing Soviet army would find witnesses to their crimes. SS officers, German soldiers, and even airplanes searched the area. Locals were offered rewards for helping. Several SS officers involved in the search received medals.

German documents show that 59 escapees were caught in nearby villages on October 17 and 18. The Germans found weapons, including a hand grenade. A few days later, five more Jewish people were killed by German soldiers. Another eight were killed nearby. In total, records show at least 107 escapees were killed by Germans. Another 23 were killed by non-Germans. One historian estimates about 30 died in other ways before the war ended.

On October 19, SS chief Himmler ordered the camp to be closed. Jewish slave laborers were sent from Treblinka to dismantle Sobibor. They destroyed the gas chambers and most camp buildings. But they left some barracks for future use. The work was finished by the end of October. All the Jewish people brought from Treblinka were killed between November 1 and November 10.

After the War

Survivors' Stories

Several thousand people sent to Sobibor were not immediately killed. They were sent to slave-labor camps in the Lublin area. These people spent only a few hours at Sobibor. They were quickly transferred to places like Majdanek. There, they prepared stolen goods for shipment to Germany. Other labor camps included Krychów and Trawniki. Most of these prisoners were murdered in a large massacre in November 1943. Or they died in other ways before the war ended. Of the 34,313 Jewish people sent to Sobibor from the Netherlands, only 18 are known to have survived the war. In June 2019, the last known survivor of the revolt, Simjon Rosenfeld, died at age 96.

Trials for War Crimes

Most people who committed crimes in Operation Reinhard were never brought to justice. But there were several trials for Sobibor officers after the war. Erich Bauer was the first SS officer from Sobibor to be tried. He was arrested in 1946. Two former Jewish prisoners recognized him at a fair in Berlin. In May 1950, Bauer was sentenced to death for his crimes. But his sentence was changed to life in prison. This was because West Germany had ended the death penalty. One survivor who testified against Bauer said, "This nothing had such power?" The next trials were for Hubert Gomerski and Johann Klier. Gomerski got a life sentence. Klier was found not guilty, partly because a survivor spoke in his favor.

The main Sobibor trials were called the Hagen Trials. They took place in West Germany. Twelve people were on trial, including Karl Frenzel and Kurt Bolender. Frenzel was sentenced to life in prison. This was for personally killing 6 Jewish people and helping murder 150,000 others. Bolender died before his sentence. Five others got shorter sentences. The rest were found not guilty.

In the 1970s and 1980s, some SS men were tried again. Gomerski was eventually freed. This was because he was too sick to be part of the trials. Later, Frenzel's life sentence was confirmed after another trial.

In the Soviet Union, there were trials for Soviet citizens who had been watchmen at Sobibor. In April 1963, a court in Kyiv found eleven former watchmen guilty. Ten were sentenced to death. One got 15 years in prison. In June 1965, three more watchmen were found guilty and executed. Another six were executed in Krasnodar.

In May 2011, John Demjanjuk was found guilty. He was an accessory to the murder of 28,060 Jewish people. He had served as a watchman at Sobibor. He was sentenced to five years in prison. But he was released while waiting for an appeal. He died in 2012 at age 91.

The Sobibor Site Today

The Germans left the area in July 1944. In August, a Soviet officer photographed the site. He also wrote a report. After the German occupation ended, the camp's remaining barracks were used for a short time. They housed Ukrainian civilians waiting to be moved. These people took apart some buildings for firewood. Parts of the Vorlager were later sold to private owners. But most of the camp site went back to the Polish forestry service.

A Polish report from 1945 noted that locals had taken apart most of the remaining camp buildings. They reused parts in their own homes. This was confirmed in 2010. A person living near the camp found unusual woodwork during a home renovation. They knew the previous owner worked near the camp. So they told researchers from the Sobibor Museum. The researchers concluded the wood came from a camp barracks. The site was also dug up by people looking for valuables. They searched for items left by the victims. When experts studied the site in 1945, they found trenches dug by treasure-seekers. These trenches had ashes and human remains on the surface. This digging continued despite some people being prosecuted in the 1960s.

For the first twenty years after the war, the camp site was almost empty. A journalist visiting in the early 1950s said, "there is nothing left in Sobibor." When a writer visited in 1972, she drove past it without knowing. She later said she was struck by "the quiet, the loneliness, above all the vastness of the place."

The first monuments to Sobibor victims were put up in 1965. They included a memorial wall, a tall stone representing the gas chambers, a sculpture of a mother and child, and a burial mound. The memorial wall first listed Jews as just one group killed at Sobibor. But the plaque was changed in 1993. It now shows that almost all victims of Sobibor were Jewish.

In 1993, the Włodawa Museum took over the memorial. They opened the Sobibór Museum on October 14, 1993. This was the 50th anniversary of the revolt. The museum was in a building that used to be a kindergarten. In 2012, the memorial was transferred again. It is now controlled by the Majdanek State Museum. They held a design competition for a new museum building.

In 2018, the mass graves in Lager III were covered with white stones. Construction began on a new museum building. But most of the site is still privately owned or managed by the forestry service. The camp's arrival ramp was used for loading lumber as recently as 2015. The only remaining building from the camp is the green post office. This building is privately owned.

Ongoing Research

Right after the war, several investigations took place. Starting in 1945, Polish groups investigated Sobibor. They interviewed witnesses and surveyed the site. In 1946, a study called "The Death Camp – Sobibór" was published. More information about Sobibor was gathered for a book called The Black Book of Polish Jewry.

Until the 1990s, little was known about the physical camp site. We only had what survivors and perpetrators remembered. Archaeological digs at Sobibor began in the 1990s. In 2001, a team found seven large pits in the former Lager III area. Some of these pits were mass graves. Others might have been used for burning bodies outdoors. The team also found barbed wire in trees. They realized these were parts of the camp's fence. This helped them map out the camp's edges, which were not known before.

In 2007, two archaeologists started small digs. Since 2013, a team of Polish, Israeli, Slovak, and Dutch archaeologists has been excavating the camp. They avoid mass graves to respect Jewish law. Their discovery of the gas chamber foundations in 2014 gained worldwide attention. Between 2011 and 2015, thousands of personal items belonging to victims were found. At the arrival ramp, large piles of household items were found. These included "glasses, combs, cutlery, plates, watches, coins, razors, thimbles, scissors, toothpaste." But few valuable items were found. This suggests victims hoped to survive as forced laborers. In Lager III, the killing area, household items were not found. But "gold fillings, dentures, pendants, earrings, and a gold ring" were found.

In 2020, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum got a collection of photos and documents. They came from the family of Johann Niemann. These photos show daily life among the camp staff. Many show them playing music and chess. These photos are important because before, only two photos of Sobibor during its operation were known. These materials have been published in a German book. The photos received a lot of media attention. Two of them seem to show John Demjanjuk in the camp.

Films and TV Shows

The details of the Sobibor death camp were explored in interviews for the 1985 documentary film Shoah. In 2001, the director used unused interviews with a survivor to tell the story of the revolt and escape in his follow-up documentary Sobibor, October 14, 1943, 4 p.m.

A fictionalized version of the Sobibor revolt was shown in the 1978 American TV show Holocaust.

The revolt was also made into a movie. This was the 1987 British TV film Escape from Sobibor. It was based on a book. Survivors helped as consultants for the film.

More recently, the revolt was shown in the 2018 Russian movie Sobibor. This movie showed Sasha Pechersky as a Russian hero. Some people criticized this portrayal.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |