Minsk facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Minsk

Мінск · Минск

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Clockwise from top: Minsk business district (Pieramozhcaw Avenue), the Church of Sts. Peter and Paul, Railway Station Square, the Red Church, National Opera and Ballet Theatre, and Minsk City Hall

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

| Country | Belarus | ||

| First mentioned | 1067 | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 409.53 km2 (158.12 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 280.6 m (920.6 ft) | ||

| Population

(2024)

|

|||

| • Total | 1,992,862 | ||

| • Density | 4,866.22/km2 (12,603.45/sq mi) | ||

| GDP | |||

| • Total | Br 65.5 billion (€18.4 billion) |

||

| • Per capita | Br 33,000 (€9,300) |

||

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK) | ||

| Postal Code |

220001-220141

|

||

| Area code(s) | +375 17 | ||

| ISO 3166 code | BY-HM | ||

| License plate | 7 | ||

Minsk (Belarusian: Мінск, IPA: [mʲinsk]; Russian: Минск) is the capital and largest city of Belarus. It is located on the Svislach and Niamiha rivers. Minsk has a special administrative status in Belarus. It is also the main city for the Minsk Region and Minsk District.

As of 2024, about two million people live in Minsk. This makes it the 11th-most populated city in Europe. Minsk is also an important center for the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). The CIS is a group of countries that used to be part of the Soviet Union. It is also a center for the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which promotes economic cooperation.

Minsk was first mentioned in 1067. It became the capital of the Principality of Minsk, a smaller part of the Principality of Polotsk. In 1242, it joined the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The city gained special town privileges in 1499. From 1569, it was the capital of a region called Minsk Voivodeship within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

In 1793, Russia took control of Minsk during the Second Partition of Poland. After the Russian Revolution, from 1919 to 1991, Minsk was the capital of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. This republic became part of the Soviet Union in 1922. When the Soviet Union broke up, Minsk became the capital of the new, independent Republic of Belarus.

Contents

City Name and Its History

The old name for Minsk was Měnskъ. This name came from a river called Měn. Over time, the name became Minsk in both Russian and Polish. Because of Russian influence, this became the official name in Belarusian too.

However, some Belarusian speakers still prefer to use the name Miensk. This is the direct Belarusian version of the name.

When Belarus was under Polish rule, people used names like Mińsk Litewski (Minsk of Lithuania) or Mińsk Białoruski (Minsk of Belarus). This helped tell it apart from another city called Mińsk Mazowiecki in Poland. Today, if someone says "Mińsk" in Polish, they usually mean the much larger city in Belarus.

History of Minsk

Early Beginnings

The Svislach River valley was a border between two early Slavic tribes. Around 980, this area became part of the Principality of Polotsk. This was one of the first Slavic kingdoms in Kievan Rus'.

Minsk was first mentioned in a historical record in 1067. This was during a battle on the Nemiga River. Most people agree that 1067 is the year Minsk was founded. The city already had wooden walls by then. The exact meaning of the name is still a mystery.

In the early 1100s, the Principality of Polotsk split into smaller parts. One of these was the Principality of Minsk. In 1129, a stronger kingdom, Kiev, took over Minsk. But by 1146, the Polotsk family got control back. By 1150, Minsk was as important as Polotsk. The princes of both cities fought to unite the lands that once belonged to Polotsk.

Later Middle Ages

Minsk was lucky and avoided the Mongol invasion of Rus' in 1237–1239. In 1242, Minsk became part of the growing Grand Duchy of Lithuania. This happened peacefully, and local leaders had important roles in the Grand Duchy.

In 1413, Lithuania and Poland joined together. Minsk became the center of the Minsk Voivodeship (a province). In 1441, Grand Duke Casimir IV gave Minsk special rights. In 1499, under his son Alexander I, Minsk received town privileges under Magdeburg rights. This meant the city could govern itself more.

In 1569, Lithuania and Poland formed one large country, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. By the mid-1500s, Minsk was a key place for trade and culture in this Commonwealth. It was also important for the Eastern Orthodox Church. Later, other Christian churches also grew in influence.

In 1655, Russian troops took over Minsk. They ruled until 1660 when the Polish-Lithuanian king got it back. After this war, Minsk had only about 2,000 people and 300 houses. The city was damaged again during the Great Northern War (1708-1709). Minsk became a small, less important town in the last years of Polish rule.

Russian Rule

Russia took Minsk in 1793. This happened after the Second Partition of Poland. In 1796, Minsk became the center of the Minsk Governorate (a Russian province). All street names were changed to Russian. French troops briefly occupied Minsk in 1812.

Throughout the 1800s, Minsk grew and improved a lot. By the 1830s, major streets were paved. The first public library opened in 1836, and a fire department started in 1837. The first local newspaper began in 1838. A theater was built in 1844.

By 1860, Minsk was a big trading city with 27,000 people. Many two- and three-story brick houses were built. Transportation also improved. A road from Moscow to Warsaw went through Minsk in 1846. Railways connected Minsk to Moscow and Warsaw in 1871, and to Ukraine and the Baltic Sea in 1873. Minsk became an important railway and manufacturing center.

The city got a water supply in 1872, telephones in 1890, and electric power in 1894. By 1900, Minsk had 58 factories and 3,000 workers. It also had theaters, cinemas, newspapers, schools, and many churches. In 1897, the city had 91,494 people. Over half of them were Jewish.

20th Century Changes

In the early 1900s, Minsk was a key place for workers' movements in Belarus. The first meeting of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (which later became the Bolsheviks) was held here in 1898. Minsk was also important for the Belarusian national revival, a time when people wanted to bring back Belarusian culture and language.

First World War greatly affected Minsk. By 1915, it was a battlefront city. Factories closed, and people moved east. Minsk became the main base for the Russian army's Western Front.

The Russian Revolution quickly changed Minsk. A Workers' Soviet (council) was formed in October 1917. German forces occupied Minsk in February 1918. On March 25, 1918, Minsk was declared the capital of the short-lived Belarusian People's Republic. In December 1918, the Red Army took over.

In January 1919, Minsk became the capital of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. This republic later joined the Soviet Union. The city was briefly controlled by Poland during the Polish–Soviet War in 1919 and 1920. After the war, Minsk was returned to the Russian SFSR and remained the capital of the Byelorussian SSR.

Reconstruction and development began in 1922. By 1924, 29 factories were working. Schools, museums, theaters, and libraries were also built. Minsk grew quickly in the 1920s and 1930s. Many new factories, schools, and hospitals opened. During this time, Minsk was also a center for Belarusian language and culture.

Before Second World War, Minsk had 300,000 people. German forces captured Minsk in 1941 as part of Operation Barbarossa. The city was heavily damaged by air raids. Some factories and many civilians were moved to the east. The Germans made Minsk an administrative center. Many people were killed or imprisoned.

Minsk became the site of one of the largest Nazi-run ghettos, holding over 100,000 Jewish people. By 1942, Minsk was a major center for the Soviet resistance movement against the Germans. Because of this, Minsk was given the title Hero City in 1974.

Soviet troops recaptured Minsk on July 3, 1944. The city was almost completely destroyed. Factories, buildings, power stations, bridges, and 80% of houses were ruined. In 1944, Minsk's population was only 50,000.

The old city center was rebuilt in the 1940s and 1950s with grand buildings and wide avenues. The city grew fast due to industrialization. Since the 1960s, Minsk's population has also grown quickly. It reached 1 million in 1972 and 1.5 million in 1986.

Construction of the Minsk Metro (subway) began in 1977. It opened on June 30, 1984. The population growth was mainly due to people moving from rural areas of Belarus. To house them, new districts with many apartment buildings were built.

Recent Developments

After the fall of Communism in the 1990s, Minsk continued to change. As the capital of a new independent country, it gained new features. Embassies opened, and Soviet buildings became government centers.

In the early 1990s, Minsk faced economic problems. Many projects stopped, and unemployment was high. Since the late 1990s, things have improved. Transportation and housing have seen big changes since 2002. New residential areas have been built on the city's edges. Subway lines have been extended, and roads improved. Minsk is still developing, with new areas planned outside the city center.

Geography and Climate

Minsk is on the southeastern slope of the Minsk Hills. These are rolling hills that stretch across Belarus. The city's average height above sea level is about 220 meters. Minsk's landscape was shaped by the last two ice ages.

The Svislach River flows through the city. It is in an old river valley formed by melting ice sheets. Six smaller rivers also flow within the city limits. All these rivers eventually flow into the Black Sea.

Minsk is in an area of mixed forests. Pine and mixed forests are found around the city, especially in the north and east. Some of these forests have been kept as parks, like Chelyuskinites Park. The city was first built on hills, which helped with defense. The western parts of Minsk are the most hilly.

About 5 kilometers from the city's northwestern edge is the large Zaslawskaye reservoir. It is often called the Minsk Sea. This is the second largest reservoir in Belarus, built in 1956.

Climate of Minsk

Minsk has a warm summer humid continental climate. This means it has four distinct seasons. Its weather can be unpredictable because it is between the moist air from the Atlantic Ocean and the dry air from Eurasia.

The average temperature in January is about -4.2°C. In July, the average is about 19.1°C. The coldest temperature ever recorded was -39.1°C in 1940. The warmest was 35.8°C in 2015. Fog is common, especially in autumn and spring.

Minsk gets about 686 millimeters of rain and snow each year. About one-third of this falls in winter, and two-thirds in summer. Winds usually come from the west or northwest. These winds bring cool, moist air from the Atlantic.

| Climate data for Minsk (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1887–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 10.3 (50.5) |

13.6 (56.5) |

24.6 (76.3) |

28.8 (83.8) |

30.9 (87.6) |

35.8 (96.4) |

35.2 (95.4) |

35.8 (96.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

24.7 (76.5) |

16.0 (60.8) |

11.1 (52.0) |

35.8 (96.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −2 (28) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

4.5 (40.1) |

12.8 (55.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

22.4 (72.3) |

24.3 (75.7) |

23.6 (74.5) |

17.5 (63.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.2 (24.4) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

0.7 (33.3) |

7.6 (45.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

17.1 (62.8) |

19.1 (66.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

12.7 (54.9) |

6.7 (44.1) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

7.2 (45.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −6.3 (20.7) |

−6 (21) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

2.9 (37.2) |

8.3 (46.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

14.4 (57.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −39.1 (−38.4) |

−35.1 (−31.2) |

−30.5 (−22.9) |

−18.4 (−1.1) |

−5 (23) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.3 (39.7) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

−20.4 (−4.7) |

−30.6 (−23.1) |

−39.1 (−38.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 47 (1.9) |

40 (1.6) |

41 (1.6) |

43 (1.7) |

66 (2.6) |

79 (3.1) |

97 (3.8) |

71 (2.8) |

51 (2.0) |

55 (2.2) |

49 (1.9) |

47 (1.9) |

686 (27.0) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 11 (4.3) |

16 (6.3) |

13 (5.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2 (0.8) |

6 (2.4) |

16 (6.3) |

| Average rainy days | 11 | 9 | 11 | 13 | 18 | 19 | 18 | 15 | 18 | 18 | 17 | 13 | 180 |

| Average snowy days | 24 | 21 | 15 | 4 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 | 3 | 13 | 22 | 102 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86 | 83 | 77 | 67 | 66 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 79 | 82 | 88 | 88 | 77 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 37.4 | 59.1 | 136.9 | 196.6 | 255.3 | 275.4 | 267.4 | 239.6 | 172.0 | 96.0 | 34.0 | 24.2 | 1,793.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 18 | 24 | 37 | 43 | 52 | 54 | 53 | 53 | 43 | 30 | 14 | 12 | 40 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Belarus Department of Hydrometeorology (persent sun from 1938, 1940, and 1945–2000), NOAA | |||||||||||||

Environmental Situation

The environment in Minsk is watched by a special center. Between 2003 and 2008, the amount of pollution increased. This was partly because factories started using mazut (a type of fuel oil) instead of gas to save money.

However, most of the air pollution comes from cars. The traffic police hold an event called "Clean Air" every year. This helps stop cars with very polluting engines. Sometimes, the levels of certain chemicals in the air are too high in some areas. The southeastern parts of Minsk are the most polluted.

People of Minsk

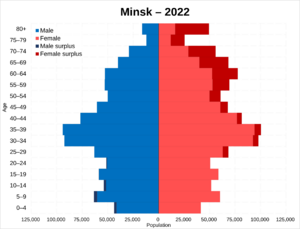

Population Growth

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1450 | 5,000 | — |

| 1654 | 10,000 | +100.0% |

| 1667 | 2,000 | −80.0% |

| 1790 | 7,000 | +250.0% |

| 1811 | 11,000 | +57.1% |

| 1813 | 3,500 | −68.2% |

| 1860 | 27,000 | +671.4% |

| 1897 | 91,000 | +237.0% |

| 1917 | 134,500 | +47.8% |

| 1941 | 300,000 | +123.0% |

| 1944 | 50,000 | −83.3% |

| 1951 | 306,913 | +513.8% |

| 1956 | 438,709 | +42.9% |

| 1961 | 580,833 | +32.4% |

| 1966 | 758,319 | +30.6% |

| 1971 | 966,515 | +27.5% |

| 1976 | 1,161,999 | +20.2% |

| 1981 | 1,350,492 | +16.2% |

| 1986 | 1,515,745 | +12.2% |

| 1991 | 1,624,724 | +7.2% |

| 2001 | 1,714,949 | +5.6% |

| 2011 | 1,868,657 | +9.0% |

| 2021 | 2,038,822 | +9.1% |

| 2022 | 1,996,553 | −2.1% |

| 2023 | 1,995,471 | −0.1% |

| Population size may be affected by changes in administrative divisions. | ||

Ethnic Groups

For many centuries, Minsk was mainly home to early East Slavic people, who are the ancestors of today's Belarusians. After 1569, when Poland and Lithuania joined, more Poles and Jews moved to the city. Poles often worked in government or as teachers. Jews worked in trade and crafts.

After 1793, Minsk became part of the Russian Empire. Russians then became the main cultural group.

In 1897, Jewish people were the largest group in Minsk, making up 52% of the population. Other large groups were Russians (25.5%), Poles (11.4%), and Belarusians (9%). Some Belarusians might have been counted as Russians. A small community of Lipka Tatars had lived in Minsk for hundreds of years.

Between the 1880s and 1930s, many Jewish people and others moved from Minsk to the United States.

After World War II, many people from rural Belarus moved to Minsk. This increased the number of ethnic Belarusians. Many skilled Russians and others from the Soviet Union also moved for jobs in factories. In 1959, Belarusians made up 63.3% of the city's people. Other groups included Russians (22.8%) and Jews (7.8%).

By 1979, Belarusians were 68.4% of the population. After the Soviet Union broke up, many Russians and Ukrainians moved back to their home countries. Today, Belarusians make up 79.3% of Minsk's residents.

The Jewish population in Minsk was highest in the early 1970s. Since the 1980s, many have moved to Israel, the US, and Germany. Today, about 10,000 Jewish people live in Minsk. The number of Poles and Tatars has stayed about the same.

New groups have also moved to Minsk. People from the Caucasus (like Armenians, Azerbaijanis, and Georgians) started coming in the 1970s. Many work in markets. A small Arab community has also grown, often from students who stayed after graduating from Minsk universities. About 2,000 Romani live in Minsk's suburbs.

Languages Spoken

Minsk has always been a city with many languages. At first, most people spoke Ruthenian, which later became modern Belarusian. After 1569, Polish became the official language. In the 1800s, Russian became the official language for government and schools.

The Belarusian national revival in the late 1800s increased interest in the Belarusian language. In the 1920s and early 1930s, Belarusian was the main language in Minsk for government and education. However, from the late 1930s, Russian became more common again.

In the early 1990s, more people started speaking Belarusian. But since 1994, this trend has changed. Most people in Minsk now use Russian every day at home and work. However, Belarusian is still understood. Some people from rural areas use Trasianka, a mix of Russian and Belarusian.

Religions in Minsk

There are no exact numbers on how many people in Minsk belong to different religions. Most Christians are part of the Belarusian Orthodox Church. This church is connected to the Russian Orthodox Church. There is also a notable number of Roman Catholics.

As of 2006, Minsk has about 30 religious communities of different faiths. The only working monastery in the city is St Elisabeth Convent. Its large group of churches is open to visitors.

Economy and Industry

Minsk is the main economic center of Belarus. It has strong industrial and service industries that help the whole country. Minsk contributes almost 46% of Belarus's budget. In 2010, Minsk paid 15 trillion Belarusian rubles to the state budget.

In 2012, Minsk's economy was mainly driven by industry (26.4%), wholesale trade (19.9%), transportation and communication (12.3%), retail (8.6%), and construction (5.8%). Minsk has the highest salaries in Belarus. In December 2023, the average monthly salary was about 3,240 BYN (around US$1,000).

Major Industries

Minsk is a major industrial city in Belarus. In 2012, companies in Minsk produced a lot of the country's goods. For example, they made 21.5% of electricity, 76% of trucks, and 89.3% of television sets.

Today, the city has over 250 factories. Its industrial growth began in the 1860s, helped by the railways built in the 1870s. Much of the industry was destroyed during World War I and II. After the last war, Minsk became a major producer of trucks, tractors, optical equipment, refrigerators, and TVs. Besides machines and electronics, Minsk also has textile, construction, food processing, and printing industries.

During the Soviet era, Minsk's industries were connected to suppliers and markets across the USSR. When the Soviet Union broke up in 1991, it caused economic problems. However, Minsk did not lose as many factories as other cities in the region. About 40% of workers are still employed in manufacturing.

Major industrial companies include:

- Minsk Tractor Plant: Makes tractors. It was started in 1946 and employs about 30,000 people.

- Minsk Automobile Plant: Makes trucks, buses, and mini-vans. It started in 1944 and is a major vehicle maker.

- Minsk Refrigerator Plant (Atlant): Makes home appliances like refrigerators, freezers, and washing machines. It started in 1959.

- Horizont: Makes TVs, audio, and video electronics. It started in 1950.

Culture and Arts

Minsk is the main cultural center of Belarus. Its first theaters and libraries opened in the mid-1800s. Today, Minsk has 11 theaters, 16 museums, 20 cinemas, and 139 libraries.

Churches of Minsk

- The Orthodox Cathedral of the Holy Spirit was once a convent church. It was built in the Baroque style between 1642 and 1687.

- The Cathedral of Saint Mary was built by Jesuits from 1700 to 1710. It faces the city hall on Liberty Square.

- Other old churches include the Cathedral of Saint Joseph, built in 1644–52, and the fortified Church of Sts. Peter and Paul, built in the 1620s.

- The Church of St. Thomas Aquinas and the Dominican monastery in Minsk was a Catholic monastery complex from the early 1600s. It was destroyed in 1950.

- The impressive Neo-Romanesque Roman Catholic Red Church was built from 1906 to 1910. This was after people gained more religious freedom.

- The largest church built during Russian rule is dedicated to St. Mary Magdalene.

- The Church of St. Adalbert and Benedictine monastery was a Catholic monastery. Today, the General Prosecutor's Office is on this site.

- Many Orthodox churches were built after the Soviet Union ended. They often follow the Neo-Russian style. St. Elisabeth's Convent, founded in 1999, is a good example.

-

Church of Holy Trinity (Saint Rochus) (Roman Catholic).

-

Minsk Cathedral of the Holy Spirit (Russian Orthodox).

Cemeteries

- Kalvaryja (Calvary Cemetery) is the oldest cemetery in Minsk. Many famous Belarusians are buried here. It closed for new burials in the 1960s.

- Military Cemetery

- Eastern Cemetery (Minsk)|Eastern Cemetery

- Čyžoŭskija Cemetery (Minsk)|Čyžoŭskija Cemetery

- Northern Cemetery (Minsk)|Northern Cemetery

Theatres

Some of the main theaters are:

- National Academic Grand Opera and Ballet Theatre of the Republic of Belarus

- Belarusian State Musical Theatre (shows in Russian)

- Maxim Gorky National Drama Theatre (shows in Russian)

- Janka Kupala National Theatre (shows in Belarusian)

Museums

Some of the main museums include:

- Belarusian National Arts Museum

- Belarusian Great Patriotic War Museum

- Belarusian National History and Culture Museum

- Belarusian Nature and Environment Museum

- Maksim Bahdanovič Literary Museum

- Old Belarusian History Museum

- Yanka Kupala Literary Museum

Art galleries include:

- Ў gallery

Recreation Areas

- Chelyuskinites Park

- Children's Railroad

- Gorky Park (Minsk)

- Yanka Kupala Park

Tourism

Minsk has over 400 travel agencies. Many of them help people plan trips and tours.

Sports in Minsk

Football Teams

- FC Dinamo Minsk

- FC Minsk

- FC Energetik-BGU Minsk

- FC Krumkachy Minsk

Ice Hockey Teams

- HC Dinamo Minsk

- HC Yunost Minsk

Handball Team

- SKA Minsk

Basketball Team

- BC Tsmoki-Minsk

International Sporting Events

In 2013, Minsk hosted the European Junior Rowing Championships. The city also hosted the 2014 IIHF World Championship for ice hockey at the Minsk Arena.

In January 2016, the 2016 European Speed Skating Championships took place at the Minsk Arena. This is Belarus's only indoor speed skating rink. Minsk hosted the 2019 European Games in June. The 2019 European Figure Skating Championships were also held at the Minsk Arena in January.

Transportation in Minsk

Local Transport

Minsk has a large public transport system. It includes 8 tram lines, over 70 trolleybus lines, 3 subway lines, and over 100 bus lines. Trams were the first public transport, starting with horse-trams in 1892 and electric trams in 1929. Public buses began in 1924, and trolleybuses in 1952.

All public transport is run by Minsktrans, a government company. As of November 2021, Minsktrans used many buses, trolleybuses, and tram cars. The number of vehicles is more than double the minimum needed for the city's population.

Public transport prices are set by the city council. A single ticket for a bus, trolleybus, or tram costs 0.75 BYN (about USD 0.3). A subway ticket costs 0.80 BYN. Express buses cost 0.90 BYN. A monthly pass for one type of transport is 33 BYN, and for all five types, it's 61 BYN. Private mini-vans (marshrutkas) cost between 1.5 and 2 BYN.

Subway System

Minsk is the only city in Belarus with a subway system. Construction began in 1977, and the first line opened in 1984. It now has three lines: Maskoŭskaja, Aŭtazavodskaja, and Zielienalužskaja. These lines are 19.1, 18.1, and 3.5 kilometers long, respectively. They have 15, 14, and 4 stations. New stations opened in 2012 and 2014. The third line opened its first part in 2020.

Minsk's subway is used by about 800,000 passengers daily. In 2017, it had 284.1 million passengers. This makes it the 5th busiest subway system in the former USSR. During busy times, trains run every 2–2.5 minutes. Most new subway stations have lifts, making them accessible for people with disabilities.

Railway and Intercity Bus

Minsk is a major transport hub in Belarus. It is where the Warsaw-Moscow railway (built in 1871) and the Liepaja-Romny railway (built in 1873) cross. The first railway connects Russia with Poland and Germany. The second connects Ukraine with Lithuania and Latvia.

They meet at the Minsk-Pasažyrski railway station, the city's main station. The original station was built in 1873. It was destroyed in World War II and rebuilt. The current modern station was built between 1991 and 2002. Minsk now has one of the most modern railway stations in the CIS.

There is also an intercity bus station. It connects Minsk to the airport, nearby towns, and other cities in Belarus and neighboring countries. There are frequent buses to Moscow, Smolensk, Vilnius, Riga, and Warsaw.

Cycling in Minsk

A 2019 survey showed that Minsk has about 811,000 adult bicycles. This means there is one bike for every 1.9 people. The total number of bikes is more than the number of cars (770,000). About 39% of Minsk residents own a bike. 43% ride a bicycle at least once a month.

Since 2015, an annual bicycle parade is held in Minsk. During this event, a main avenue is closed to cars for several hours. In 2019, over 20,000 people took part. In 2017, the European Union helped fund a project to develop cycling in Belarus. In 2020, Minsk was among the top 3 cycling cities in the CIS.

Airports

Minsk National Airport is located 42 kilometers east of the city. It opened in 1982 and is an international airport. It has flights to Europe and the Middle East. The old Minsk-1 Airport closed in 2015. Minsk Borovaya Airfield is a smaller airfield near the city. It houses a flying club and the Minsk Aviation Museum.

Education in Minsk

Minsk has about 451 kindergartens, 241 schools, 22 colleges, and 29 higher education institutions. This includes 12 major national universities.

Major Universities

- Academy of Public Administration: Established in 1991, it trains people for government jobs.

- Belarusian State University: A major university founded in 1921. It has many departments like Biology, Economics, History, and Law. It employs over 2,400 lecturers.

- Research Institute for Nuclear Problems of Belarusian State University

- Belarusian State University of Agricultural Technology: Focuses on farming technology and machinery.

- Belarusian National Technical University: Specializes in technical subjects.

- Belarusian State Medical University: Specializes in Medicine and Dentistry. It became a separate university in 1930.

- Belarusian State Economic University: Focuses on Finance and Economics. It started in 1933.

- Maxim Tank Belarusian State Pedagogical University: Trains teachers for secondary schools.

- Belarusian State University of Informatics and Radioelectronics: Specializes in IT and radio electronics.

- Belarusian State University of Physical Training: Trains sports coaches and physical education teachers.

- Belarusian State Technological University: Specializes in chemical, pharmaceutical, printing, and forestry technologies.

- Minsk State Linguistic University: Specializes in foreign languages. It focuses on English, French, German, and Spanish.

- Belarusian State University of Culture and Arts: Specializes in cultural studies and performing arts.

- International Sakharov Environmental Institute: Focuses on environmental sciences. It was set up in 1992 to study the effects of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

- Minsk Institute of Management: The largest private university in Belarus. It teaches Economics, Management, Marketing, and IT.

Honors

A minor planet called 3012 Minsk was discovered in 1979. It was named after the city.

Famous People from Minsk

- Viktar Babaryka (born 1963), a Belarusian public figure.

- Maksim Bahdanovič (1891–1917), a poet and founder of modern Belarusian literature.

- Olga Chupris (born 1969), the first female Vice-Rector of Belarusian State University.

- Louis B. Mayer (1884–1957), an American film producer who co-founded Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

- Alexander Rybak (born 1986), winner of the Eurovision Song Contest 2009.

- Stanislav Shushkevich (1934–2022), the first head of independent Belarus.

Musicians

- Angelica Agurbash (born 1970), a Belarusian singer and Eurovision participant.

- Yung Lean (born 1996), a Swedish rapper and musician.

Sports Figures

- Andrei Arlovski (born 1979), a mixed martial artist.

- Victoria Azarenka (born 1989), a former World No. 1 tennis player.

- Svetlana Boginskaya (born 1973), a gold medal-winning gymnast.

- Darya Domracheva (born 1986), a biathlete with four Olympic gold medals.

- Boris Gelfand (born 1968), an Israeli chess Grandmaster.

- Max Mirnyi (born 1977), a tennis player.

- Yulia Raskina (born 1982), a rhythmic gymnast who won Olympic silver.

- Aryna Sabalenka (born 1998), a 2023 Australian Open winner and former World No. 1 tennis player.

- Roman Sorkin (born 1996), a Belarusian-born Israeli basketball player.

Sister Cities

Minsk is twinned with many cities around the world, including:

- Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (2007)

- Ankara, Turkey (2007)

- Bangalore, India (1986)

- Beijing, China (2016)

- Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan (1997)

- Bonn, Germany (1993)

- Changchun, China (1992)

- Chişinău, Moldova (2000)

- Detroit, United States (1979)

- Dushanbe, Tajikistan (1998)

- Eindhoven, Netherlands (1994)

- Gaziantep, Turkey (2018)

- Hanoi, Vietnam (2004)

- Havana, Cuba (2005)

- Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (2008)

- Islamabad, Pakistan (2015)

- Kaluga, Russia (2015)

- Murmansk, Russia (2014)

- Nizhny Novgorod, Russia (2017)

- Novosibirsk, Russia (2012)

- Rostov-on-Don, Russia (2018)

- Sendai, Japan (1973)

- Shanghai, China (2019)

- Shenzhen, China (2014)

- Tbilisi, Georgia (2015)

- Tehran, Iran (2006)

- Ufa, Russia (2017)

- Ulyanovsk, Russia (2015)

Images for kids

-

The Saviour Church, built under the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1577, is part of an archaeological preservation in Zaslavl, 23 km (14 mi) northwest of Minsk.

-

Meeting in the Kurapaty woods, 1989, where between 1937 and 1941 from 30,000 to 250,000 Belarusian intelligentsia members were murdered by the NKVD during the Great Purge

-

Independence Avenue (Initial part of avenue candidates for inclusion in World Heritage Site)

-

Jewish Holocaust memorial "The Pit" in Minsk

See also

In Spanish: Minsk para niños

In Spanish: Minsk para niños