International Committee of the Red Cross facts for kids

|

Comité international de la Croix-Rouge

Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja |

|

| Formation | 17 February 1863 |

|---|---|

| Type | International NGO |

| Purpose | Protecting victims of conflicts and providing them with assistance |

| Headquarters | Geneva, Switzerland |

|

Region served

|

Worldwide |

| Field | Humanitarianism |

|

President

|

Mirjana Spoljaric Egger |

|

Vice President

|

Gilles Carbonnier |

|

Director-General

|

Pierre Krähenbühl |

|

Budget

|

CHF 1576.7 million (2016) 203.7 m for headquarters 1462.0 m for field operations |

|

Staff

|

15,448 (average number of ICRC staff in 2016) |

| Award(s) |

|

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is a special organization based in Geneva, Switzerland. It helps people affected by wars and violence. The ICRC has won the Nobel Peace Prize three times for its important work.

This group has been very important in creating the rules of war. These rules help protect people during conflicts. The ICRC also works to spread humanitarian ideas, which means treating everyone with kindness and respect.

Countries that signed the Geneva Convention of 1949 and its later agreements have given the ICRC a big job. This job is to protect people caught in international and local armed conflicts. These people include wounded soldiers, prisoners, refugees, civilians, and others not fighting.

The ICRC is part of the larger International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. This movement also includes the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and 191 national Red Cross and Red Crescent groups. The ICRC is the oldest and most respected part of this movement. It is known worldwide for its work.

Contents

History of the Red Cross

How the ICRC Started

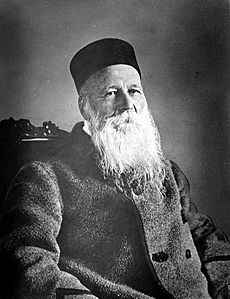

Before the mid-1800s, there were no organized systems to help wounded soldiers. There were also no safe places to treat them on the battlefield. In June 1859, a Swiss businessman named Henry Dunant was in Italy. He saw the terrible results of the Battle of Solferino. About 40,000 soldiers were killed or wounded in just one day.

Henry Dunant was shocked by the suffering and the lack of medical care. He stopped his original plans and spent days helping the wounded. He got local people to help everyone, no matter which side they were on.

Back home in Geneva, he wrote a book called A Memory of Solferino in 1862. He sent copies to important leaders in Europe. In his book, he suggested two main ideas:

- Create national groups of volunteers to help wounded soldiers during war.

- Make international agreements to protect wounded people, medics, and hospitals.

On February 9, 1863, a group in Geneva decided to look into Dunant's ideas. They formed a small committee of five members. These members included Dunant, a lawyer named Gustave Moynier, two doctors (Louis Appia and Théodore Maunoir), and a general (Guillaume-Henri Dufour).

Just eight days later, on February 17, 1863, these five men met. They decided to form a "Permanent International Committee." This committee would continue to help wounded people in war.

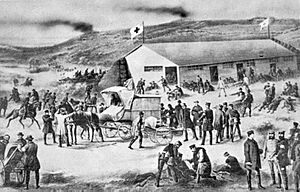

In October 1863, the Committee held a meeting in Geneva. People from 14 countries attended. They discussed ways to improve medical help on battlefields. The meeting led to important ideas:

- Start national groups to help wounded soldiers.

- Protect wounded soldiers and keep them neutral.

- Use volunteers to help on the battlefield.

- Hold more meetings to make these ideas into international laws.

- Use a special symbol for medical staff: a white armband with a red cross. This honored Switzerland's neutrality by reversing its flag colors.

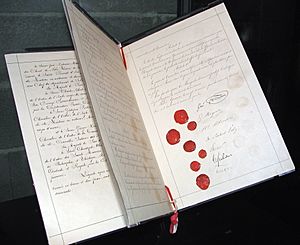

One year later, the Swiss government invited countries to a meeting. On August 22, 1864, the first Geneva Convention was signed. It was called "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field." Representatives from 12 countries signed it.

This convention had ten rules. For the first time, it created laws to protect wounded soldiers, medical staff, and hospitals during war. It also set rules for national relief groups to be recognized by the International Committee.

Soon after, the first national Red Cross groups were formed in many European countries. In 1864, Louis Appia and Charles van de Velde became the first neutral delegates to work under the Red Cross symbol in a conflict.

In 1867, Henry Dunant faced business problems and had to leave Geneva. He never returned. The committee later changed its name to the "International Committee of the Red Cross" (ICRC) in 1876. Five years later, the American Red Cross was started by Clara Barton. More and more countries signed the Geneva Convention. The Red Cross quickly became a respected international movement.

In 1901, Henry Dunant shared the first Nobel Peace Prize with another peace activist. This award helped restore Dunant's reputation and honored his role in starting the Red Cross. He passed away nine years later.

The Geneva Convention was updated in 1906. In 1907, the Hague Convention extended the rules to naval warfare. By 1914, 50 years after the ICRC began, there were 45 national Red Cross groups around the world.

The Red Cross During World War I

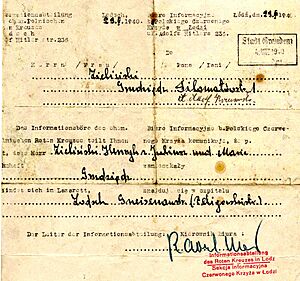

When World War I began, the ICRC faced huge challenges. They worked closely with national Red Cross groups. Nurses from many countries helped the armies. On October 15, 1914, the ICRC set up its International Prisoners-of-War (POW) Agency. This agency had about 1,200 staff, mostly volunteers.

By the end of the war, the Agency had sent 20 million letters and messages. They also sent 1.9 million packages and 18 million Swiss francs in money to POWs. About 200,000 prisoners were exchanged or sent home because of the Agency. The Agency kept 7 million records of prisoners and missing people. This helped identify 2 million POWs and connect them with their families.

During the war, the ICRC checked if countries followed the Geneva Conventions. They protested when chemical weapons were used for the first time. Even without a specific rule, the ICRC tried to help civilians. They visited 524 POW camps across Europe.

The ICRC also published postcards showing prisoners in camps. This was to give hope to families. After the war, the ICRC helped 420,000 prisoners return home. In 1917, the ICRC received the Nobel Peace Prize for its work during the war. It was the only Nobel Peace Prize given between 1914 and 1918.

After the war, the League of Red Cross Societies was founded in 1919. This group aimed to coordinate the work of national Red Cross societies. The relationship between the ICRC and this new League was sometimes difficult.

In 1923, the ICRC changed its rules. Before, only citizens from Geneva could be members. Now, all Swiss citizens could join. In 1925, a new rule was added to the Geneva Convention, banning poisonous gases and biological weapons. In 1929, the second Geneva Convention was created, focusing on the treatment of prisoners of war.

The Red Cross During World War II

During World War II, the ICRC continued its work. They visited POW camps, helped civilians, and exchanged messages for prisoners and missing people. By the end of the war, 179 delegates had visited 12,750 POW camps in 41 countries. The Central Information Agency for Prisoners-of-War had 3,000 staff and 45 million cards tracking prisoners. They exchanged 120 million messages.

However, there were big challenges. The German Red Cross, controlled by the Nazis, refused to follow the Geneva rules. Also, the Soviet Union and Japan had not signed the 1929 Geneva Conventions. This meant they were not legally bound by its rules.

The ICRC faced its biggest challenge with the Holocaust. They struggled to get agreements with Nazi Germany about concentration camp detainees. The ICRC later admitted that it failed to act decisively to help the victims of Nazi persecution. They consider this their greatest failure.

After November 1943, the ICRC was allowed to send packages to some concentration camp detainees. They managed to register about 105,000 detainees and delivered 1.1 million packages.

Swiss historians have studied the Red Cross records. They found that the Red Cross knew about the Nazi plans to kill Jews by November 1942. However, they did not tell the public. The ICRC was based in Geneva and funded by the Swiss government, so it was careful not to upset Switzerland's neutral stance.

In March 1945, the ICRC got permission to visit concentration camps. Ten delegates visited camps like Mauthausen and Dachau. One delegate, Louis Haefliger, saved about 60,000 inmates at Mauthausen. His actions were first criticized by the ICRC but later recognized as heroic.

In 1944, the ICRC received its second Nobel Peace Prize. It was the only Peace Prize given during World War II. After the war, the ICRC helped organize aid for affected countries. Since 1996, the ICRC's records from this period have been open for research.

Later Years: 20th Century and Beyond

In 1948, the ICRC helped with a large relief program for Palestinian refugees.

On August 12, 1949, the Geneva Conventions were updated again. A new convention was added to protect wounded, sick, and shipwrecked soldiers at sea. The 1929 convention for prisoners of war became the Third Geneva Convention. A very important new convention, the Fourth Geneva Convention, was created to protect civilians during war. Later, in 1977, additional rules were added to make the conventions apply to internal conflicts like civil wars. Today, these conventions have over 600 rules, much more than the original 10 rules from 1864.

In 1963, the ICRC and the League of Red Cross Societies received their third Nobel Peace Prize, celebrating 100 years of work. Since 1993, people who are not Swiss can work as ICRC delegates abroad. Now, about 35% of the staff are not Swiss citizens.

In 1990, the UN General Assembly gave the ICRC a special "observer status." This means the ICRC can attend UN meetings. In 1993, an agreement with the Swiss government confirmed the ICRC's full independence from Switzerland. This agreement protects ICRC property, gives staff legal immunity, and frees the ICRC from taxes.

The ICRC continued its work in the 1990s. They spoke out against the Rwandan genocide in 1994. They tried to prevent crimes in Srebrenica in 1995, but admitted their impact was limited. In 2007, they spoke out against human rights abuses in Burma.

Remembering the Holocaust

In 1995, the ICRC President, Cornelio Sommaruga, attended a ceremony to remember the liberation of Auschwitz concentration camp. He wanted to show that the ICRC understood the seriousness of the The Holocaust. He expressed regret for the Red Cross's past mistakes regarding the victims of concentration camps.

The ICRC has learned important lessons from its past failures:

- They created the Geneva Convention to protect civilians in war.

- They adopted the "Fundamental Principles of the Red Cross and Red Crescent" to prevent future problems.

- They changed their relationship with Switzerland to ensure independence.

- They took over the International Tracing Service in 1955, which keeps records from concentration camps.

- They allowed historians to study their archives to understand what happened.

On January 27, 2005, the 60th anniversary of Auschwitz's liberation, the ICRC stated: "Auschwitz also represents the greatest failure in the history of the ICRC, aggravated by its lack of decisiveness in taking steps to aid the victims of Nazi persecution."

Rules for Cyberwarfare

On October 4, 2023, the ICRC released a set of rules for civilian hackers. These rules explain how hackers should act during conflicts to avoid harming civilians and critical services.

Staff Fatalities

Working for the ICRC can be very dangerous. Many delegates have lost their lives, especially in local conflicts. These incidents often show that people do not respect the rules of the Geneva Conventions or the Red Cross symbols.

Some of the delegates who have been killed while working for the ICRC include:

- Richard Heider (1942, Greece)

- Matthaeus Vischer (1943, Indonesia)

- Johann Jovanovits (1946, Germany)

- Otto Anderegg (1946, Indonesia)

- Charles Huber (1946, Germany)

- Georges Olivet (1961, Democratic Republic of Congo)

- Robert Carlsson and Dragan Hercog (1968, Nigeria)

- Jacob Sturzenegger (1975, Vietnam)

- Louis Gaulis (1978, Lebanon)

- Alain Bieri, André Tieche, Charles Chatora (1978, Zimbabwe)

- Christine Rieben (1980, Uganda)

- Jürg Baumann (1980, Sudan)

- André Redard (1982, Angola)

- Alain Jossi (1984, Ethiopia)

- Michel Zufferey (1985, Sudan)

- Marc Blaser (1985, Angola)

- Catherine Chappuis, Nuno Ferreira (1987, Angola)

- Pernette Zehnder (1987, Lebanon)

- Juanito Patong, Walter Berweger (1990, Philippines)

- Mohammad Zamany (1990, Afghanistan)

- Yar Faqir (1990, Afghanistan)

- Peter Altwegg (1990, Somalia)

- Rais Khan, Mostu Khan (1991, Afghanistan)

- Anthony Arulanthu (1991, Sri Lanka)

- Wim Van-Boxelaere (1991, Somalia)

- Jón Karlsson (1992, Afghanistan)

- Frédéric Maurice (1992, Sarajevo, Yugoslavia)

- Solomon Jarboe (1992, Liberia)

- Kurt Lustenberger (1993, Somalia)

- Sarah Leomy, Suzanne Buser (1993, Sierra Leone)

- Michel Kuhn (1993, Tajikistan)

- Antoine Munderere (1993, Rwanda)

- Angela Gago-Gallego, Julia Narrea (1994, Peru)

- Kiew Sambath (1994, Cambodia)

- Rodrigues Cambiote (1994, Angola)

- Fernanda Calado, Ingeborg Foss, Nancy Malloy, Gunnhild Myklebust, Sheryl Thayer, and Hans Elkerbout (1996, Chechnya)

- Rita Fox, Véronique Saro, Julio Delgado, Unen Ufoirworth, Aduwe Boboli, and Jean Molokabonge (2001, Democratic Republic of Congo)

- Ricardo Munguia (2003, Afghanistan)

- Vatche Arslanian (2003, Iraq)

- Nadisha Yasassri Ranmuthu (2003, Iraq)

- Emmerich Pregetter (2008, Sudan)

- Kristofer Scott (2011, Liberia)

- Khalil Dale (2012, Pakistan)

- Hussein Saleh (2012, Yemen)

- Abdul Bashir-Khan (2013, Afghanistan)

- Dieudonné Ruhamanyi, Pascal Barholere (2013, Democratic Republic of the Congo)

- Siradjou Mamadou (2014, Central African Republic)

- Michael Greub (2014, Libya)

- Laurent Du Pasquier (2014, Ukraine)

- Hamadoun Daou (2015, Mali)

- Mohammed Al-Hakami, Abdulkarem Ghazi (2015, Yemen)

- Alexis Marboua (2016, Central African Republic)

- Emmanuel Lukudu, Ghulam Maqsood, Ghulam Rasoul, Ghulam Mortaza, Ahmad Khalid, Najibullah Sahebzada, Sayed Shah-Agha (2017, Afghanistan)

- Lorena Enebral-Perez (2017, Afghanistan)

- Atteyipe Youssouf (2017, Central African Republic)

- Hanna Lahoud (2018, Yemen)

- Saifura Hussaini (2019, Nigeria)

- Hauwa Liman (2019, Nigeria)

- Saidi Kayiranga, Ahmed Wazir, Hamid Al-Qadami, John Kaka (2020, South Sudan)

- Diomede Nzobambona (2021, Cameroon)

- On September 12, 2024, three ICRC staff were killed in the Donetsk region.

In 2011, the ICRC started the Health Care In Danger campaign. This campaign highlights the dangers faced by healthcare workers in humanitarian crises.

What Makes the ICRC Special

The ICRC's original motto is Inter Arma Caritas, which means "Amidst War, Charity." This motto shows their main goal. The ICRC uses three official languages: English, French, and Spanish. Its symbol is a red cross on a white background, which is the reverse of the Swiss flag. The words "COMITE INTERNATIONAL GENEVE" circle the cross.

Under the Geneva Convention, the red cross, red crescent, and red crystal symbols protect military medical services and aid workers in conflicts. These symbols are placed on humanitarian vehicles and buildings. The Red Crescent was adopted by the Ottoman Empire. The Red Crystal was added in 2005 as a symbol without any national, political, or religious meaning.

ICRC's Main Goals

The ICRC's official mission is to "protect the lives and dignity of victims of war and internal violence and to provide them with assistance." They are an impartial, neutral, and independent organization. They also help with relief efforts and work to strengthen international humanitarian law.

The main jobs of the ICRC, based on the Geneva Conventions, are:

- To check if countries fighting are following the Geneva Conventions.

- To organize care for wounded people on the battlefield.

- To check on prisoners of war and talk privately with the authorities holding them.

- To help find missing people during a conflict (tracing service).

- To organize protection and care for civilians.

- To act as a neutral go-between for fighting groups.

In 1965, the ICRC created seven basic principles for the whole Red Cross Movement: humanity, impartiality, neutrality, independence, volunteerism, unity, and universality.

Legal Status and Funding

The ICRC is the only organization specifically named in international humanitarian law as a controlling authority. Its legal power comes from the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and its own rules. The ICRC also does work not specifically required by law, like visiting political prisoners outside of conflicts or helping in natural disasters.

The ICRC is a private Swiss association. It has special privileges and legal protections in Switzerland. An agreement with the Swiss government in 1993 protects its property, gives staff legal immunity, and frees it from taxes.

The ICRC's members are only Swiss citizens. New members are chosen by the Committee itself. However, since the 1990s, the ICRC hires people from all over the world to work in its field missions. In 2007, almost half of the ICRC staff were not Swiss.

The ICRC's work is based on international humanitarian law. This includes the Geneva Conventions and their additional rules. The first Geneva Convention was signed in 1864.

- The First Geneva Convention of 1949 protects the wounded and sick on land.

- The Second Geneva Convention protects the wounded, sick, and shipwrecked at sea.

- The Third Geneva Convention deals with the treatment of prisoners of war.

- The Fourth Geneva Convention protects civilians during war.

The ICRC's budget for 2023 was 2.5 billion Swiss francs. Most of this money comes from countries, especially Switzerland, and from national Red Cross societies. All payments to the ICRC are voluntary donations. In 2023, Ukraine was the ICRC's biggest operation, followed by Afghanistan and Syria.

In March 2023, the ICRC announced budget cuts and job losses due to a drop in donations. This was partly because the Russian invasion of Ukraine drew attention and funds away from other crises. In May 2023, the Canton of Geneva pledged 40 million Swiss francs in emergency donations to help the ICRC.

Roles within the Red Cross Movement

The ICRC is responsible for officially recognizing a relief group as a national Red Cross or Red Crescent society. Once recognized by the ICRC, a national society can join the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). The ICRC and the IFRC work with national societies on international missions.

According to the 1997 Seville Agreement, the ICRC leads Red Cross efforts in conflicts. Other organizations in the movement lead in non-war situations. National societies lead when a conflict happens in their own country.

Acceptance of Magen David Adom

From 1930 until 2006, the Magen David Adom (MDA), Israel's equivalent to the Red Cross, was not accepted into the movement. This was because it used the Star of David as its symbol, which the ICRC saw as religious. This meant that MDA ambulances were not protected by the Geneva Conventions.

In 2005, the ICRC adopted a new symbol called the Red Crystal. Magen David Adom then placed its Star of David inside the Red Crystal shape. After this, it was accepted as a full member of the Movement in 2006.

Working with Countries

The ICRC prefers to talk directly with countries. They use quiet, private discussions to get access to prisoners of war and improve their treatment. Their findings are not usually made public. This is different from groups like Doctors Without Borders who might publicly criticize governments. The ICRC believes its approach helps them gain more access and cooperation in the long run.

If they only get partial access, the ICRC takes what they can get. They keep working quietly for more access. For example, during apartheid South Africa, they could visit prisoners like Nelson Mandela. After his release, Mandela praised the Red Cross. He said they helped improve prisoner treatment.

People Who Have Worked for the ICRC

Many important people have worked for the ICRC, including:

- Louis Appia (co-founder)

- Henry Dunant (founder)

- Marguerite Frick-Cramer (historian, early female member)

- Max Huber (jurist, former president)

- Marcel Junod (physician)

- Jakob Kellenberger (diplomat, former president)

- Pierre Krähenbühl (Director General)

- Théodore Maunoir (surgeon, co-founder)

- Peter Maurer (historian, former president)

- Gustave Moynier (jurist, co-founder)

- Jean Pictet (Doctor of Law)

- Cornelio Sommaruga (diplomat, former president)

- Mirjana Spoljaric Egger (diplomat, current president)

Images for kids

-

Marcel Junod, delegate of the ICRC, visiting POWs in Nazi Germany

(Benoit Junod, Switzerland)

See also

In Spanish: Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja para niños

In Spanish: Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |