Marcel Junod facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Marcel Junod

|

|

|---|---|

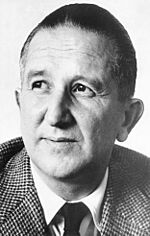

Marcel Junod in 1952 (© Benoit Junod, Switzerland)

|

|

| Born | 14 May 1904 Neuchâtel, Switzerland

|

| Died | 16 June 1961 (aged 57) Geneva, Switzerland

|

| Known for | International Committee of the Red Cross |

Marcel Junod (14 May 1904 – 16 June 1961) was a Swiss doctor who became one of the most important field delegates for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). He traveled to many war zones, helping people caught in conflicts.

After finishing medical school, he worked as a surgeon. Then, he joined the ICRC and was sent to Ethiopia during the Second Italo-Abyssinian War. He also worked in Spain during the Spanish Civil War, and in Europe and Japan during World War II.

In 1947, he wrote a book called Warrior without Weapons about his amazing experiences. After the war, he helped children in China for United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). Later, he started the first department for anaesthesiology (medicine that makes you sleep for surgery) at the Cantonal Hospital in Geneva. He even became a professor at the University of Geneva.

Marcel Junod became a member of the ICRC in 1952. He continued his missions and served as Vice-President from 1959 until he passed away in 1961.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Marcel Junod was born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, on May 14, 1904. He was the fifth of seven children. His father was a pastor who worked in poor communities. Marcel spent most of his childhood in La Chaux-de-Fonds. After his father died, his family moved to Geneva. His mother and aunt opened a boarding house to support the family.

In 1923, Marcel finished his early education at Geneva's Collège Calvin. This was the same school attended by Henry Dunant, who founded the Red Cross. As a student, Marcel volunteered to help others. He even directed a movement to help Russian children in Geneva.

Thanks to his uncle's financial help, Marcel was able to study medicine. He went to universities in Geneva and Strasbourg, becoming a doctor in 1929. He chose to specialize in surgery and worked at hospitals in Geneva and Mulhouse, France, from 1931 to 1935. After finishing his training, he became the head of the surgical clinic in Mulhouse.

Helping People During Wars

Marcel Junod became a delegate for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). This meant he was sent to places where wars were happening to help people.

The War in Ethiopia (1935-1936)

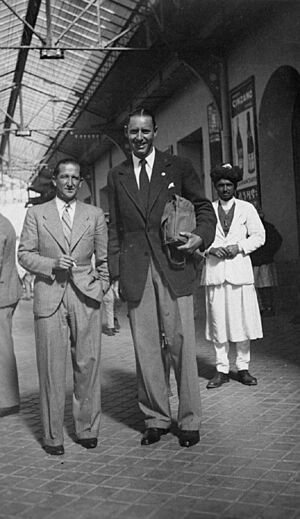

In October 1935, Marcel Junod was asked to go to Ethiopia. Italy had just invaded the country. He quickly accepted the offer and traveled to Addis Ababa with another ICRC delegate, Sidney Brown. He stayed in Ethiopia until the war ended in May 1936.

Sidney Brown helped set up a Red Cross Society in Ethiopia. Marcel Junod focused on organizing and coordinating Red Cross ambulances. These ambulances were sent by Red Cross societies from different countries like Egypt, Finland, and the UK. The Ethiopian Red Cross accepted help, but the Italian Red Cross refused any cooperation.

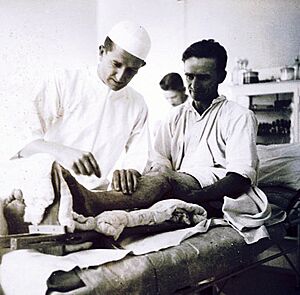

Marcel Junod faced many challenges. Italian soldiers and Ethiopian armed groups attacked Red Cross ambulances. One bombing killed 28 Red Cross workers and patients. He also saw terrible things, like the bombing of the city Dessie and the use of mustard gas on civilians. He witnessed the suffering of many people.

Junod wrote about these difficult times:

- . . . Men were stretched out everywhere beneath the trees. There must have been thousands of them. As I came closer, my heart in my mouth, I could see horrible suppurating burns on their feet and on their emaciated limbs. Life was already leaving bodies burned with mustard gas.

- 'Abiet . . . Abiet . . . .'

- The monotonous chant rose towards the refuge of the Emperor. But who was to have pity? Who was to help them in their suffering? There were no doctors available and our ambulances had been destroyed. . . .

-

(Dr. Marcel Junod: Warrior without Weapons. ICRC, Geneva, 1982, p. 61)

The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939)

In July 1936, a civil war broke out in Spain. The ICRC asked Marcel Junod to go there. He was supposed to stay for three weeks, but he ended up staying for over three years! The ICRC sent more delegates, and Marcel led a team of nine people across the country.

It was hard for the Red Cross to work because the Geneva Conventions (rules for war) didn't fully apply to civil wars. Marcel suggested creating a special group with representatives from both sides of the conflict. This group would help release captured women and children and create safe zones. However, the warring parties could not agree.

Despite these difficulties, Marcel Junod convinced both sides to make agreements. These agreements helped exchange prisoners and saved many lives. Before the city of Barcelona fell, he managed to get 5,000 prisoners released. He also started using the Red Cross card system for the first time in a civil conflict. This system helped families find out if their loved ones were alive or missing. By the end of the war, the ICRC had exchanged five million cards.

He described the importance of these cards:

- . . . Someone was on the other side of the line and his nearest did not even know whether he was alive or dead.

- For a long time I had realized that this uncertainty was the greatest agony of all. I had seen too many trembling hand stretched out for the sheet of paper that we had at last succeeded in getting from one side to the other: the Red Cross card.

- There was not much on it: a name and address and a message which was not allowed to exceed twenty-five words. Often when it came back the censor had left only the signature on it, but at least it was proof that a loved one was still alive. And then the eyes which read the name and the signature would fill with tears of joy. . . .

-

(Dr. Marcel Junod: Warrior without Weapons ICRC, Geneva, 1982, p. 115)

World War II Missions (1939-1945)

When World War II began, Marcel Junod was called back to Geneva by the ICRC. He became an ICRC delegate again, starting his mission in Berlin in September 1939. For a long time, he was the only ICRC delegate in Germany. Just eleven days later, he visited a camp with Polish prisoners of war (POWs). In June 1940, he stopped the planned executions of French POWs. He also helped organize the exchange of information about POWs with the ICRC office in Geneva.

His main jobs during this war were to make sure the Geneva Conventions were followed in POW camps. He also helped distribute food and medical supplies to civilians in occupied areas. This help for civilians was not officially part of the ICRC's role until 1949. To get supplies to people, Junod helped start using Red Cross ships. These ships were specially marked with neutral symbols of the ICRC. Sadly, on June 9, 1942, one of these ships, the "Sturebog," was sunk by an Italian aircraft, even though it had neutral markings.

Junod shared the tragic story of the "Sturebog":

- . . . For three weeks we impatiently awaited news that the Sturebog had arrived back safely in Alexandria. Geneva inquired vainly after her whereabouts in London, Rome, Berlin and Ankara. The Sturebog was lost at sea and we began to think that we should never learn anything about her fate.

- . . . Then one morning on the coast of Palestine two Bedouins going along the shore found a body half buried in the sand. . . . He was the sole survivor of the Sturebog, a Portuguese sailor. Gradually he recovered and after a week he was able to tell his tale.

- The day after the departure of the Sturebog from Piraeus two Italian planes flew overhead. They flew round in circles and had plenty of time to observe the huge red crosses painted on the ship's white side. Nevertheless they dropped a bomb which cut the Sturebog in half. . . .

-

(Dr. Marcel Junod: Warrior without Weapons ICRC, Geneva, 1982, p. 202)

In December 1944, Marcel married Eugénie Georgette Perret. After a short break, he was sent to Japan in June 1945, arriving in Tokyo on August 9. His first job was to visit POWs in Japanese camps. His wife was expecting their child at home.

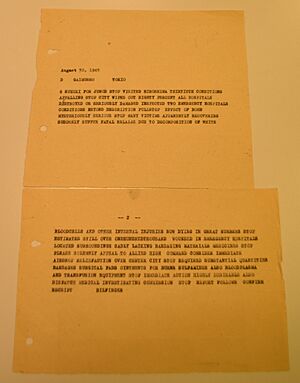

After the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima (August 6, 1945) and Nagasaki (August 9, 1945), Japan surrendered. Junod quickly organized help for POW camps and helped rescue injured prisoners. On August 30, he received photos and a telegram describing the terrible conditions in Hiroshima. He quickly put together a rescue mission.

On September 8, Marcel Junod became the first foreign doctor to reach Hiroshima. He brought 15 tons of medical supplies. He stayed for five days, visiting hospitals, giving out supplies, and personally helping the injured. The photos he sent to the ICRC were some of the first pictures of Hiroshima after the bombing to reach Europe.

He wrote about the haunting scene in Hiroshima:

- . . . On what remained of the station facade the hands of the clock had been stopped by the fire at 8.15.

- It was perhaps the first time in the history of humanity that the birth of a new era was recorded on the face of a clock. . . .

-

(Dr. Marcel Junod: Warrior without Weapons ICRC, Geneva, 1982, p. 300)

Life After World War II

Marcel Junod stayed in Japan and other Asian countries until April 1946. He returned to Switzerland, having missed the birth of his son, Benoit, in October 1945. After returning home, he wrote his famous book, Warrior Without Weapons. The book shares his personal experiences during his many ICRC missions. It has been translated into many languages and is often called the "bedside volume of all young ICRC delegates."

The foreword to his book, written by former ICRC President Max Huber, explains Junod's idea of a "third combatant":

- Thus it is our task to form a third front above and cutting across the two belligerent fronts, a third front which is directed against neither of them, but which works for the benefit of both. The combatants of this third front are interested only in the suffering of the defenceless human being, irrespective of his nationality, his convictions or his past. They fight wherever they can against all inhumanity, against every degradation of the human personality, against all injustice directed against defenceless human beings. It is for these fighters that Dr. Junod has coined the expression 'the third combatant'.

-

(Dr. Marcel Junod: Warriors without Weapons. From the foreword by Max Huber, former ICRC President)

From 1948 to 1949, Junod worked for UNICEF in China. However, he became ill and had to stop this mission. He also had to give up his career as a surgeon because his illness made it hard to stand for long periods. He decided to become an anesthesiologist, which allowed him to work sitting down. He trained in Paris and London. In 1951, he returned to Geneva and opened a new medical practice.

In 1953, he convinced the Cantonal Hospital of Geneva to open an anesthesiology department. He later became its director. He also started doing medical research and shared his findings at conferences.

In 1946, the USA wanted to give Junod the Medal of Liberty for his help to Allied prisoners in Japan. However, Swiss citizens who are required to serve in the military cannot accept foreign awards. So, he could not receive it. Four years later, in 1950, he received the Gold Medal for Peace from Prince Carl of Sweden for his humanitarian work.

He became a member of the ICRC again on October 23, 1952, and was elected Vice-President in 1959. He moved to a small village near Geneva called Lullier in 1953 to find peace from his busy life. He often spent holidays with friends in Barcelona, whom he met during his mission in Spain. His work with the ICRC took him to many places, including Budapest, Vienna, and Cairo. In 1960, he visited Red Cross societies in the Soviet Union, Japan, Canada, and the United States. In December 1960, he became a Professor of Anesthesiology at the University of Geneva.

Marcel Junod passed away on June 16, 1961, in Geneva. He had a massive heart attack while working as an anesthesiologist during an operation. The ICRC received over 3,000 messages of sympathy from all over the world. That same year, the government of Japan gave him the Order of the Sacred Treasure after his death.

On September 8, 1979, a monument to Marcel Junod was placed in the Hiroshima Peace Park. Every year, a meeting is held there to remember him. On September 13, 2005, 60 years after he left Hiroshima, a similar monument was placed in Geneva.

The last sentence of Marcel Junod's book is written on the back of the Hiroshima monument:

- . . . All these pictures are not merely out of the past. They are still with us all today and they will be with us still more tomorrow. Those wounded men and those pitiful captives are not things in a nightmare; they are near us now. Their fate is in our care. Let us place no reliance on the slender hope which lawyers have aroused by devising a form of words to place a check on violence. There will never be too many volunteers to answer so many cries of pain, to answer so many half-stifled appeals from the depths of prison and prison camp.

- Those who call for help are many. It is you they are calling.

-

(Dr. Marcel Junod: Warrior without Weapons ICRC, Geneva, 1982, p. 312)

Images for kids