Chiune Sugihara facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Chiune Sugihara

|

|

|---|---|

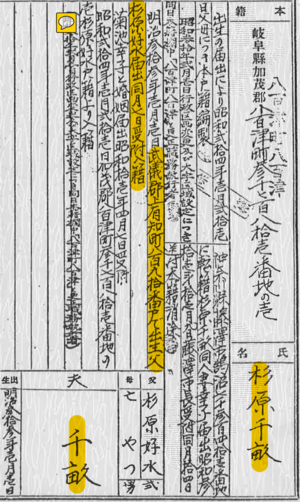

| 杉原 千畝 | |

Sugihara, before 1945

|

|

| Born | 1 January 1900 Kozuchi Town, Empire of Japan (now Mino, Gifu Prefecture, Japan)

|

| Died | 31 July 1986 (aged 86) Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan

|

| Resting place | Kamakura Cemetery |

| Other names | "Sempo", Sergei Pavlovich Sugihara |

| Occupation | Vice-consul for the Japanese Empire in Lithuania |

| Known for | Rescue of 5,558 Jews during the Holocaust |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 4 |

| Awards |

|

Chiune Sugihara (杉原 千畝, Sugihara Chiune, 1 January 1900 – 31 July 1986) was a Japanese diplomat who worked as a vice-consul for the Japanese Empire in Kaunas, Lithuania. During World War II, Sugihara helped thousands of Jewish people escape Europe. He did this by giving them special travel visas so they could pass through Japanese territory. This was a very brave act, as it put his job and his family's safety at risk.

The Jewish people he helped were refugees from German-occupied Western Poland and Soviet-occupied Eastern Poland, as well as people living in Lithuania. In 1985, the State of Israel honored Sugihara as one of the Righteous Among the Nations. This is a special title given to non-Jewish people who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. He is the only Japanese person to receive this honor. It's believed that as many as 100,000 people alive today are descendants of those who received Sugihara's visas.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Chiune Sugihara was born on January 1, 1900, in Mino, Gifu prefecture, Japan. His father, Yoshimi Sugihara, worked at a tax office. Chiune was the second of six children. His family moved several times during his childhood.

He went to elementary school and later graduated with high honors from Furuwatari Elementary School. His father wanted him to become a doctor. However, Chiune had other plans. He purposely failed the entrance exam for medical school. Instead, in 1918, he went to Waseda University to study English.

In 1919, he passed an important exam for the Foreign Ministry Scholarship. From 1920 to 1922, Sugihara served in the Imperial Japanese Army in Korea. He left the army in 1922. The next year, he passed a difficult Russian language exam for the Foreign Ministry. He was then sent to Harbin, China, where he became an expert on Russian affairs.

Manchurian Foreign Office Work

While working in the Manchurian Foreign Office, Sugihara helped with talks between Japan and the Soviet Union. These talks were about the Northern Manchurian Railroad.

In Harbin, Sugihara married Klaudia Semionovna Apollonova. He also became a Christian, joining the Russian Orthodox Church. He used the baptismal name Sergei Pavlovich.

In 1934, Sugihara resigned from his job in Manchuria. He did this to protest how the Japanese were treating the local Chinese people. Sugihara and Klaudia divorced in 1935. He then returned to Japan and married Yukiko Kikuchi. They had four sons: Hiroki, Chiaki, Haruki, and Nobuki. As of 2021, Nobuki is the only surviving son.

Sugihara also worked for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in other roles. He was a translator for the Japanese team in Helsinki, Finland.

Helping Refugees in Lithuania

In 1939, Sugihara became the vice-consul at the Japanese Consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania. His job included watching Soviet and German troop movements. He also had to report if Germany planned to attack the Soviets.

Sugihara worked with Polish intelligence as part of a larger Japanese-Polish plan. In Lithuania, he started using the name "Sempo" for his first name. It was easier for others to say than "Chiune."

Jewish Refugees Seek Help

When the Soviet Union occupied sovereign Lithuania in 1940, many Jewish refugees from Poland and Lithuanian Jews needed to leave. They needed exit visas to travel safely. But it was very hard to find countries willing to give them visas. Hundreds of refugees came to the Japanese consulate in Kaunas, hoping for a visa to Japan.

At this time, on the edge of war, Jewish people made up a large part of Lithuania's city populations. Between July 16 and August 3, 1940, another diplomat, Jan Zwartendijk, gave over 2,200 Jews passes to Curaçao. This was a Dutch island that didn't require an entry visa.

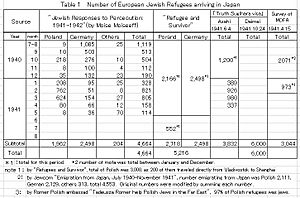

Jewish refugees from Europe started arriving in Japan in July 1940. They continued to arrive until September 1941. Many traveled across Europe and Asia by train, then by ship to Japan. From Japan, they hoped to go to countries in the Western Hemisphere.

By early 1941, thousands of Polish refugees in Lithuania needed to leave. Many were rabbis, students, and community leaders. They needed money for the train trip across Siberia to Japan. American Jewish groups helped raise funds for about 1,700 people.

Most of the refugees arriving in Japan from January 1940 to March 1941 had visas for other countries. They quickly left Japan. But starting in October 1940, many Polish refugees from Lithuania arrived. By March 1941, nearly 2,000 were in Japan, mostly in Kobe. More than half of these people did not have visas for a final destination. This meant they were stuck in Japan for a long time.

The exact number of Jewish refugees who came to Japan is debated. Estimates range from 4,500 to 6,000.

Sugihara's Brave Visas

The Japanese government had strict rules for visas. They said visas should only be given to people who had enough money and a visa for a final destination. Most refugees did not meet these rules. Sugihara asked the Japanese Foreign Ministry three times for advice. Each time, the Ministry said no exceptions could be made.

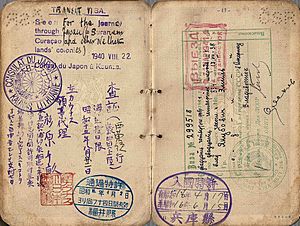

Sugihara knew that if the refugees stayed, they would be in great danger. So, he decided to ignore his orders. From July 18 to August 28, 1940, he began issuing ten-day transit visas for Japan. This was a very unusual act of disobedience for a Japanese diplomat. He also spoke with Soviet officials. They agreed to let the Jewish people travel through the Soviet Union by the Trans-Siberian railway.

Sugihara worked tirelessly, writing visas by hand for 18 to 20 hours a day. He produced a month's worth of visas every day. He continued until September 4, when he had to leave his post because the consulate was closing. By then, he had given thousands of visas. Many were for heads of families, allowing their whole families to travel.

Witnesses said he was still writing visas even as he was leaving. He wrote them in his hotel and on the train at the Kaunas Railway Station. He even threw visas out of the train window to the desperate refugees as the train pulled away.

In a final act, he quickly prepared blank papers with only the consulate seal and his signature. These could later be filled in as visas. He threw these out from the train too. As he left, he said, "Please forgive me. I cannot write anymore. I wish you the best." Someone in the crowd called out, "Sugihara. We'll never forget you. I'll surely see you again!"

Sugihara later wondered about how his government would react. He remembered, "No one ever said anything about it. I remember thinking that they probably didn't realize how many I actually issued."

How Many People Were Saved?

The exact number of people Sugihara saved is still debated. Estimates range from 2,200 to 6,000. Some believe the higher number because one visa could allow a whole family to travel. The Simon Wiesenthal Center estimates he issued visas for about 6,000 Jews. They also believe that around 40,000 descendants of these refugees are alive today because of his actions.

Many refugees used their visas to travel across the Soviet Union to Vladivostok. From there, they took a boat to Kobe, Japan. There was a Jewish community in Kobe that helped them. The Polish ambassador in Tokyo, Tadeusz Romer, also helped them get visas for other countries.

Some of the Sugihara survivors stayed in Japan. Later, they were sent to Japanese-held Shanghai, where a large Jewish community already lived. Most of the approximately 20,000 Jews in the Shanghai ghetto survived the Holocaust until Japan surrendered in 1945.

Imprisonment and Later Life

Sugihara was later sent to other diplomatic posts in Europe. When Soviet troops entered Romania, they held Sugihara and his family in a POW camp for 18 months. They were released in 1946 and returned to Japan.

In 1947, the Japanese foreign office asked him to resign. His wife, Yukiko Sugihara, said the Foreign Ministry told him he was dismissed because of "that incident" in Lithuania.

Sugihara settled in Fujisawa, Japan, with his family. He took various jobs to support them, even selling light bulbs door-to-door. He later worked for an export company and lived in the Soviet Union for 16 years, using his Russian language skills.

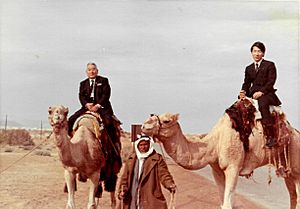

In 1968, one of the people Sugihara helped, Yehoshua Nishri, found him. Nishri was an economic attaché at the Israeli Embassy in Tokyo. The next year, Sugihara visited Israel and was welcomed by the Israeli government.

In 1984, Yad Vashem recognized him as Righteous Among the Nations. Sugihara was too ill to travel, so his wife and youngest son, Nobuki, accepted the award for him.

In 1985, he was asked why he issued the visas. Sugihara explained that the refugees were human beings who simply needed help. He said he couldn't help but feel sympathy for them. He felt it was the right thing to do, driven by a spirit of humanity and friendship.

Chiune Sugihara died on July 31, 1986, in Kamakura. He was not widely known in Japan for his actions until a large Jewish delegation, including the Israeli ambassador, attended his funeral. Only then did his neighbors learn what he had done.

Honor Restored

After his death, Chiune Sugihara's humanitarian acts became more widely known in Japan. In 1991, a Japanese official apologized to Sugihara's family for how the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had treated him. His honor was officially restored by the Japanese government on October 10, 2000.

Family

- Yukiko Sugihara (1913–2008) – his wife. She wrote a book called Visas for 6,000 Lives.

- Hiroki Sugihara (1936–2002) – eldest son. He translated his mother's book into English.

- Chiaki Sugihara (1938–2010) – second son.

- Haruki Sugihara (1940–1947) – third son. He was born in Kaunas and died young from leukemia.

- Nobuki Sugihara (1948–) – fourth son. He is the only surviving son and represents the Sugihara family. He works to promote peace.

Legacy and Honors

Many places are named after Chiune Sugihara, including Sugihara Street in Vilnius, Lithuania, and Chiune (Sempo) Sugihara Street in Jaffa, Israel. Even an asteroid, 25893 Sugihara, is named after him.

In 1992, the town of Yaotsu opened the Park of Humanity. In 2000, the Sugihara Chiune Memorial Hall opened there. Many visitors come to learn about Sugihara.

A special area for Sugihara Chiune is also in the Port of Humanity Tsuruga Museum. This museum is near Tsuruga Port, where many Jewish refugees arrived in Japan.

The Sugihara House Museum is in Kaunas, Lithuania. In the US, a synagogue in Massachusetts built a "Sugihara Memorial Garden."

When Sugihara's widow, Yukiko, visited Jerusalem in 1998, she met survivors. They showed her the old, yellowed visas her husband had signed. A park in Jerusalem is named after him. Sugihara was also featured on an Israeli postage stamp in 1998. The Japanese government honored him in 2000, on his 100th birthday.

In 2001, a sakura park with 200 trees was planted in Vilnius, Lithuania, to mark his 100th anniversary.

In 2002, a memorial statue of Chiune Sugihara was placed in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles, California. The statue shows Sugihara holding a visa. Next to it is a quote from the Talmud: "He who saves one life, saves the entire world."

He received many awards after his death. These include the Commander's Cross with the Star of the Order of Polonia Restituta and the Commander's Cross Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland. He also received the Life Saving Cross of Lithuania in 1993.

In June 2016, a street in Netanya, Israel, was named for Sugihara. His son Nobuki attended the ceremony. Many people living in Netanya today are descendants of the Lithuanian Jews he saved.

The Lithuanian government declared 2020 "The Year of Chiune Sugihara." A monument to Sugihara, with origami cranes, was unveiled in Kaunas in October 2020.

Since October 2021, there is a Chiune Sugihara Square in Jerusalem and a Garden named for him.

Biographies

Many books and films have been made about Chiune Sugihara's life and actions:

- In Search of Sugihara: The Elusive Japanese Diplomat Who Risked his Life to Rescue 10,000 Jews From the Holocaust by Hillel Levine.

- Visas for Life by Yukiko Sugihara, his wife.

- Sugihara: Conspiracy of Kindness (2000) is a documentary film from PBS.

- A Special Fate: Chiune Sugihara: Hero of the Holocaust (2000) by Alison Leslie Gold is a book for young readers.

- Visas for Life was also a two-hour drama on Japanese TV in 2005.

- Visas and Virtue (1997) is a film by Chris Tashima and Chris Donahue that won an Academy Award.

- Passage to Freedom: The Sugihara Story (2002) is a children's picture book.

- Persona Non Grata (2015) is a Japanese drama film where Toshiaki Karasawa played Sugihara.

Notable People Helped by Sugihara

Some of the notable people who were helped by Sugihara's visas include:

- Leaders and students of the Mir Yeshiva, a famous Jewish religious school.

- Yaakov Banai, an Israeli military commander.

- Leo Melamed, a financier who helped create financial futures.

- John G. Stoessinger, a professor of diplomacy.

- Zerach Warhaftig, an Israeli lawyer and politician who signed Israel's Declaration of Independence.

- Bernard and Rochelle Zell, parents of the famous businessman Sam Zell.

See also

In Spanish: Chiune Sugihara para niños

In Spanish: Chiune Sugihara para niños

- Individuals and groups assisting Jews during the Holocaust

- Aristides de Sousa Mendes

- Ho Feng-shan

- Varian Fry

- Tatsuo Osako

- Setsuzo Kotsuji

- Giorgio Perlasca

- John Rabe

- Abdol Hossein Sardari

- Oskar Schindler

- Raoul Wallenberg

- Nicholas Winton

- Jan Zwartendijk

- Persona Non Grata (2015 film)

- Nansen passport

- Ładoś Group

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |