British African-Caribbean people facts for kids

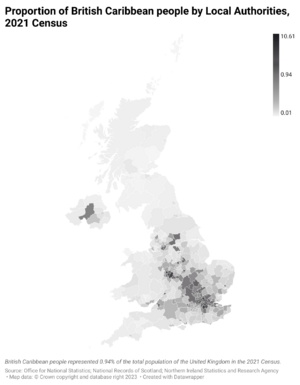

Distribution by local authority in the 2011 census

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

Northern Ireland: 2,963 – 0.2% (2021) |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| British English · Caribbean English | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity (69.1%); minority follows other faiths (2.7%) or are irreligious (18.6%) 2021 census, England and Wales only |

|

| Related ethnic groups | |

| African diaspora · African-Caribbean · Bahamian British · British Jamaicans · Guyanese British · Barbadian British · Grenadian British · Montserratian British · Trinidadian and Tobagonian British · Antiguan British |

British Afro-Caribbean people are a group of people in the United Kingdom whose families originally came from the Caribbean. Many of their ancestors were brought from West and Central Africa to the Caribbean as part of the slave trade. Some British Afro-Caribbean people are also multi-racial, meaning they have family from different backgrounds.

The term "African-Caribbean community" usually refers to groups of people who continue to share and celebrate Caribbean culture, customs, and traditions in the UK. The first Afro-Caribbean people who moved to Britain came from many different groups. They are descendants of various African peoples who were taken as slaves to the colonial Caribbean. Some British African Caribbeans also have ancestors from native Caribbean tribes, or from European and Asian ethnic groups.

Small numbers of Caribbean people have lived in British port cities since the mid-1700s. However, the biggest wave of migration happened after World War II. This was when many former British colonies in the Caribbean became independent. These new arrivals were known as the Windrush generation. They came to the UK in the 1950s and 1960s as citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies. Even though many were given the right to live in the UK permanently, some faced unfair problems with their residency status in the 2000s and 2010s. This became known as the Windrush scandal.

Today, Afro-Caribbean communities live in major cities across the UK. The people from the Windrush generation and their descendants form a diverse cultural group in the country. It can be tricky to get exact population numbers because there isn't one specific category for them in the UK census. However, categories like 'Black Caribbean' and 'Mixed: White and Black Caribbean' help track their numbers.

Contents

Understanding the Terms

A common definition for "Afro-Caribbean" or "African Caribbean" is "a person of African family origins whose family settled in the Caribbean before moving to another country." This term is often used in Europe and North America. In the UK, the term "African Caribbean" is now preferred over "Afro-Caribbean." Some people also believe the term should not be hyphenated.

Many people of African and Caribbean origin in the UK have also started using the term 'Black British'. This shows their connection to both their African or Caribbean heritage and their British identity.

Who Lives Here?

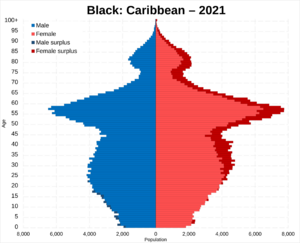

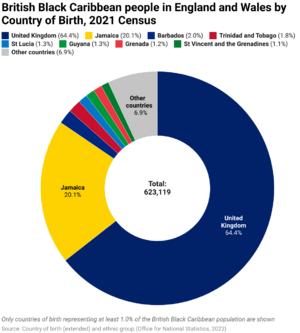

In the 2021 Census for England and Wales, about 623,115 people identified as 'Black Caribbean'. This is about 1% of the total population. The 2011 Census showed 594,825 people as "Caribbean" under the "Black/African/Caribbean/Black British" group. Another 426,715 people identified as "White and Black Caribbean" under the "Mixed/multiple ethnic group" heading.

Where People Were Born

Year of arrival (2021 census, England and Wales) Born in the UK (64.4%) Before 1950 (0.1%) 1951 to 1960 (4.4%) 1961 to 1970 (10.2%) 1971 to 1980 (2.0%) 1981 to 1990 (1.7%) 1991 to 2000 (5.6%) 2001 to 2010 (6.4%) 2011 to 2021 (5.1%)

The census also records where people were born. In the 2011 Census, 160,095 residents in England and Wales were born in Jamaica. Other significant numbers came from Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, Grenada, and St Lucia. In total, 264,125 people in England and Wales were born in the Caribbean.

Education and Learning

Black Caribbeans in the UK are more likely to have formal qualifications than White Britons. In 2011, 20% of Black Caribbeans had no qualifications, compared to 24% of White British people.

However, in the past, many Caribbean migrant children were wrongly placed in special schools. In the early 2000s, Black pupils were three times more likely than White pupils to be excluded from school. But things have improved a lot. By 2013, Black Caribbean pupils were achieving much closer to the national average in exams like GCSEs. Black Caribbean pupils from lower-income families often do better academically than White British pupils from similar backgrounds. Also, Black Caribbean pupils have a higher rate of going to university than White British students.

Jobs and Money

Socio-economic status looks at the type of work a person does. In 2011, 40.7% of Black Caribbeans were in the top three socio-economic groups (managerial, professional, and intermediate jobs). This was one of the highest percentages among all ethnic groups.

Research shows that second-generation Black Caribbean men (those born in the UK or who arrived young) have similar job levels to White British men. Black Caribbean women have even surpassed White British women in occupational class. There's also a growing Black middle class.

Black Caribbeans have one of the lowest poverty rates among ethnic minority groups in Britain. In 2007, 30% of Black Caribbeans lived in poverty, compared to higher rates for some other groups. When at least one adult in a family was working, Black Caribbeans had very low poverty rates (10-15%).

In terms of wealth, Black Caribbeans rank third among major ethnic groups in the UK. Their median net family wealth per adult was £120,000 in 2020.

| Ethnic group | Individual median wealth |

|---|---|

| White British | £166,700 |

| Indian | £144,400 |

| Black Caribbean | £85,000 |

| Chinese | £67,300 |

| White Other | £53,200 |

| Pakistani | £52,000 |

| Bangladeshi | £22,800 |

| Black African | £18,100 |

Black Caribbeans have also had high employment rates. From 2004-2008 and 2013-2014, they earned more than their White British counterparts. By 2019, Black Caribbean women continued to earn more on average than White British women.

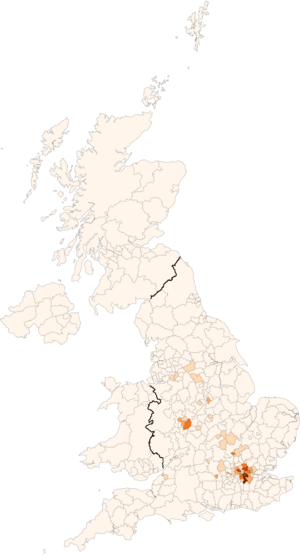

Where People Live

| Region / Country | Population | Per cent of region | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| England | 619,419 | 1.10% | |||||

| Greater London | 345,405 | 3.93% | |||||

| West Midlands | 90,192 | 1.52% | |||||

| South East | 43,523 | 0.47% | |||||

| East of England | 41,884 | 0.66% | |||||

| East Midlands | 30,828 | 0.63% | |||||

| North West | 25,919 | 0.35% | |||||

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 22,736 | 0.41% | |||||

| South West | 17,226 | 0.30% | |||||

| North East | 1,704 | 0.06% | |||||

| Wales | 3,700 | 0.12% | |||||

| Northern Ireland | 2,963 | 0.16% | |||||

| Scotland | 2,214 | 0.04% | |||||

|

|

|||||||

Most Black Caribbean people live in Greater London. In 2021, areas like Lewisham, Croydon, and Lambeth had the highest percentages. Outside London, Birmingham also has a large Black Caribbean population. Other cities with significant communities include Manchester, Nottingham, Leeds, and Bristol. These communities often have specific areas where they have traditionally settled, such as Brixton in London or Handsworth in Birmingham.

Beliefs and Religion

| Religion | England and Wales | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2021 | |||

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| 441,544 | 74.23% | 430,770 | 69.13% | |

| No religion | 76,616 | 12.88% | 116,143 | 18.64% |

| 7,345 | 1.23% | 7,167 | 1.15% | |

| 511 | 0.09% | 650 | 0.10% | |

| 1,145 | 0.19% | 1,251 | 0.20% | |

| 1,344 | 0.23% | 798 | 0.13% | |

| 349 | 0.06% | 108 | 0.02% | |

| Other religions | 4,065 | 0.68% | 6,909 | 1.11% |

| Not Stated | 61,906 | 10.41% | 59,323 | 9.52% |

Most British Afro-Caribbean people are Christian, with 69.13% identifying as such in the 2021 census. A smaller number follow other faiths or have no religion. Many Afro-Caribbean people in Britain practice Pentecostalism and Seventh Day Baptism, which are types of Protestant Christianity. These churches often serve as important social centers for the community. Some British Afro-Caribbean people also follow Rastafari, a religion that started in Jamaica.

A Look at History

Early Arrivals

From the 1500s to the 1800s, enslaved Africans were brought to British colonies in the Caribbean. They were forced to work on large plantations, growing crops like sugar and cotton. Slavery was not allowed in England itself.

Important British Afro-Caribbean figures like Ignatius Sancho helped lead the movement to end slavery in the 1700s. After slavery was abolished, small communities of freed slaves began to form in British port cities like Cardiff, Liverpool, and London.

Notable People from the 1800s

Many important Afro-Caribbean people lived in Britain during the 19th century. They include:

- Mary Seacole (1805–1881), a famous nurse during the Crimean War.

- Walter Tull, a footballer and soldier.

- Andrew Watson, another pioneering footballer.

World War II and Beyond

During World War I, about 15,000 migrants from the Caribbean came to work in British factories. In World War II, more West Indian workers arrived in places like Liverpool.

After World War II, Britain needed more workers. The government encouraged people from the British Empire and Commonwealth countries to come to the UK. The British Nationality Act 1948 gave British citizenship to all people in Commonwealth countries, allowing them to live and work in Britain. Many West Indians saw this as a chance for a better life in the "mother country."

The Windrush Generation Arrives

On June 22, 1948, the ship MV Empire Windrush arrived in Tilbury, near London, carrying 492 migrants. Many were former servicemen who wanted to return to Britain. This event is seen as the start of modern British multicultural society.

There were many jobs available in post-war Britain, especially in British Rail, the National Health Service, and public transport. However, many new arrivals faced racism and unfair treatment. They were often denied jobs and housing because of their race. Some pubs, clubs, and even churches would not allow Black people to enter.

This led to tensions and sometimes riots in cities like London and Nottingham in the 1950s. The Notting Hill Carnival was started in 1959 as a positive response by the Caribbean community after attacks in Notting Hill.

By 1962, Britain passed a law that made it harder for immigrants to enter the country. Despite these restrictions, a new generation of Britons with African-Caribbean heritage grew up, making important contributions to British society.

Challenges in the 1970s and 1980s

The 1970s and 1980s were tough times in Britain, with high unemployment. This deeply affected the African-Caribbean community. Young people from Caribbean families often faced much higher unemployment rates than white school leavers.

Societal racism, discrimination, and poverty led to a series of riots in areas with large African-Caribbean populations. These events, sometimes called "uprisings," happened in places like Brixton and Handsworth. A report called the Scarman report looked into the causes of these problems. It found "racial discrimination" and "racial disadvantage" in Britain. This report called for urgent action to prevent these issues from becoming a permanent problem in society.

Amazing Contributions

British African-Caribbean people have made huge contributions to many areas of British life.

Academia and Learning

Many African-Caribbean academics are leaders in arts and humanities. Professor Paul Gilroy is a leading academic who has taught at Harvard University. Professor Stuart Hall, born in Jamaica, was a very important British thinker. Dr. Robert Beckford has presented TV and radio shows about African-Caribbean history and culture.

Acting and Entertainment

The 1970s saw the rise of independent filmmakers like Trinidadian-born Horace Ové. The Talawa Theatre Company was founded in London in 1985 by Jamaican-born Yvonne Brewster.

African-Caribbean actors became more visible on British television. Shows like Desmond's (1989–94) showed a more positive and diverse view of Caribbean families. Famous actors include Lennie James, Judith Jacob, and Diane Parish. Peter Davison, who has Afro-Guyanese heritage, played the Doctor in Doctor Who.

One of the biggest names in British comedy is Lenny Henry. He started as a stand-up comedian and became popular with his TV sketch shows. Other TV personalities include Alison Hammond, Ainsley Harriott, Angellica Bell, and Alex Scott.

British African-Caribbean actors have also found success in US film and television. Marianne Jean-Baptiste and Naomie Harris were nominated for Academy Awards. Other successful actors include Frank Dillane, Wentworth Miller, Stephen Graham, Delroy Lindo, Colin Salmon, Marsha Thomason, Ashley Walters, David Harewood, and Lashana Lynch.

Art and Design

Professor Eddie Chambers is a very influential figure in the British art world. He co-founded the BLK Art Group in 1982. Artists like Donald Rodney and Sonia Boyce have their work in the Tate Britain museum. The exhibition The Other Story in 1986 showcased African-Caribbean, African, and Asian artists in the UK.

Other notable artists include Faisal Abdu'allah, Ingrid Pollard, and Tam Joseph, whose work Spirit of Carnival shows the Notting Hill Carnival. In 1999, filmmaker Steve McQueen won the prestigious Turner Prize.

Music Scene

In 1983, Cleo Laine, who has Jamaican heritage, won a Grammy Award for Best Female Jazz Vocal Performance. Billy Ocean, born in Trinidad, won a Grammy for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance in 1985. Steel Pulse won a Grammy for Best Reggae Album in 1987. Soul II Soul also won two Grammy Awards.

Many members of the band UB40 have Caribbean heritage. S Club 7 had two members of African-Caribbean heritage, Bradley McIntosh and Tina Barrett. Melanie Brown was part of the hugely successful Spice Girls. Leigh-Anne Pinnock is a member of Little Mix, another best-selling girl group.

Other Grammy-winning or nominated British-Caribbean artists include Estelle, Corinne Bailey Rae, Ella Mai, and Slowthai.

Sporting Heroes

British African-Caribbean people are very successful in sports like football, rugby, cricket, and athletics.

Athletics Stars

Harry Edward, born in Guyana, won Britain's first Olympic sprint medals in 1920. Sprinter Linford Christie, born in Jamaica, won a gold medal in the 100 metres at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. Hurdler Colin Jackson, who has Jamaican heritage, held the 110 metres hurdles world record for 11 years.

Ethel Scott was the first Black woman to represent Great Britain in international athletics. Jamaican-born Tessa Sanderson was the first British African-Caribbean woman to win Olympic gold in javelin in 1984. Denise Lewis, of Jamaican heritage, won heptathlon gold in the 2000 Sydney Olympics. Kelly Holmes, whose father was Jamaican, won gold in both the 800 and 1500 metres in 2004. The men's 4 × 100-metre relay team, all of African-Caribbean heritage, won Olympic gold in 2004. Jessica Ennis-Hill, of Jamaican heritage, won heptathlon gold in the 2012 London Olympics.

Boxing Champions

British boxers of Caribbean background have been very successful. Frank Bruno, whose mother was from Jamaica, became Britain's first world heavyweight boxing champion in the 20th century. Lennox Lewis, a British-born Jamaican, became the world's top heavyweight in the late 1990s. Other champions include Chris Eubank, Nigel Benn, Audley Harrison, Lloyd Honeyghan, James DeGale, David Haye, and Dillian Whyte.

Cricket Legends

Cricket is very popular among African-Caribbean people. Many great West Indian cricketers played in the English county game. British cricketers of Caribbean origin also made a big impact for England, including Gladstone Small, Devon Malcolm, and Phillip DeFreitas.

Football Greats

Andrew Watson, born in British Guiana, was one of the first West Indian-born footballers to play at a high level in Britain in the 1800s. Walter Tull, of Barbadian descent, played for Tottenham Hotspur in the early 1900s.

In the 1970s, African-Caribbean players like Clyde Best, Cyrille Regis, and Luther Blissett began to make a major impact. Blissett and Regis, along with Viv Anderson, were among the first Black footballers to play for the England national team. Even then, Black players sometimes faced racial attacks.

By the 1980s, many British African-Caribbean players were in football. John Barnes, born in Jamaica, was one of the most talented players of his time. Paul Ince, whose parents were from Trinidad, captained major clubs and the England team. Many British-born footballers also played for the Jamaica national football team in the 1998 World Cup.

In the 2006 World Cup, the England squad included many African-Caribbean players like Theo Walcott, Ashley Cole, Rio Ferdinand, and Sol Campbell. More recently, Tyrone Mings, Marcus Rashford, Raheem Sterling, and Kyle Walker have represented England.

Motorsports Champion

Lewis Hamilton, whose grandparents came from Grenada, is one of the most successful British drivers in Formula One history. He has won the Drivers' Championship seven times.

Rugby Stars

Clive Sullivan, who had Jamaican and Antiguan heritage, was the first Black captain for a Great Britain team in any sport. He led the team to win the 1972 Rugby League World Cup. Jason Robinson was the first African-Caribbean to captain the England rugby union side. Ellery Hanley, of Jamaican heritage, is considered one of the greatest players in rugby league history.

Jimmy Peters was the first Black man to play rugby union for England. Other notable players include Danny Cipriani, Jeremy Guscott, and Ashton Golding.

Cultural Impact

Carnivals and Celebrations

African-Caribbean communities organize vibrant carnivals across the UK. The most famous is the annual Notting Hill Carnival in London. It attracts millions of people and is the largest street festival in Europe. It started in 1964 to celebrate Caribbean culture. Other big carnivals include the Luton Carnival and the Leeds West Indian Carnival.

Since 2018, Windrush Day is celebrated annually on June 22. This day honors the contributions of the Windrush generation and other migrant communities in Britain.

Delicious Food

When early Caribbean immigrants arrived, it was hard to find their traditional foods. But over time, grocery stores specializing in Caribbean produce opened. Now, Caribbean restaurants are common across Britain. They serve popular dishes like curried goat, fried dumplings, ackee and salt fish, and rice and peas.

Popular Caribbean food brands in the UK include Jamaican Sun, Tropical Sun, and Grace. These products are now often found in large supermarkets, showing how popular Caribbean food has become.

Community Hubs

Many towns and cities in Britain have African-Caribbean community centres. These centers help bring communities together by arranging social events like festivals and trips. They also offer support with things like jobs, housing, and education. Examples include the Leeds West Indian Centre and the Afro Caribbean Millennium Centre in Birmingham.

Language and Dialect

English is the main language in the Caribbean, so immigrants had few communication problems in the UK. Over time, British-born African-West Indians developed new dialects that mix Caribbean and local British accents. These dialects have even influenced mainstream British English. A study found that some British accents now borrow from Jamaican creole.

Books and Stories

Jamaican poet James Berry was one of the first Caribbean writers to come to Britain after 1948. Other early writers included George Lamming and Samuel Selvon. These writers helped bring Caribbean literature to a global audience. Selvon's novel The Lonely Londoners (1956) describes the lives of West Indians in post-war London.

Later, a new wave of writers explored the African-Caribbean experience in Britain. Poets like Fred D'Aguiar and Benjamin Zephaniah became well-known.

More recently, African-Caribbean British writers have won major awards. In 2004, Andrea Levy's novel Small Island won the Whitbread Book of the Year. Zadie Smith's novel White Teeth (2000) became an international bestseller. In 2020, Candice Carty-Williams became the first Black woman to win the "Book of the Year" award for her novel Queenie.

Media and News

The Voice newspaper was a main African-Caribbean newspaper in Britain. Pride magazine is a large lifestyle magazine for the community. These publications help share news and stories relevant to the community.

Famous journalists include Trinidad-born Sir Trevor McDonald, who was a main news presenter for ITV for over 20 years. Other notable media figures include Gary Younge, Clive Myrie, and Moira Stuart.

The community also has a strong tradition of "underground" pirate radio stations. These stations play a mix of Caribbean music styles like ragga, reggae, and dancehall. They also host talk shows where the community can discuss important topics. The BBC also has a digital radio station, BBC Radio 1Xtra, which focuses on new Black music.

Musical Influence

Large-scale immigration brought many new musical styles to the UK. These styles became popular with people of all backgrounds. Early artists like Lord Kitchener brought calypso to Britain.

Jamaican music styles like ska reached Britain in the 1960s. Artists like Millie Small and Desmond Dekker helped make Caribbean music popular. British African-Caribbean bands like Symarip also made their own ska music. This sound influenced the 2 Tone movement in the late 1970s.

As Jamaican music changed to rocksteady and reggae, British African-Caribbean artists followed. The arrival of Bob Marley in London helped create a Black British music industry based on reggae. Artists like Musical Youth, Aswad, Maxi Priest, and Eddy Grant had big commercial successes. The band UB40 helped bring reggae to a global audience.

In the 1990s, British African-Caribbean artists started mixing different musical forms. They combined European techno, Jamaican dancehall, and American R&B. This led to new genres like jungle and drum and bass. DJs like Goldie and Roni Size were leaders in these movements. Later, British African-Caribbean musicians were at the forefront of UK garage and Grime music.

|

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |