Windrush scandal facts for kids

The Windrush scandal was a big problem in Britain that started in 2018. It was about people who were wrongly held, not given their legal rights, and even threatened with being sent out of the UK. In at least 83 cases, people were actually deported by the Home Office, which is a government department.

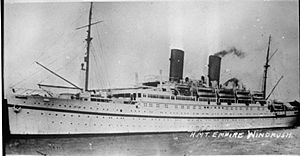

Many of these people were born as British subjects and came to the UK before 1973. They mostly came from Caribbean countries and were part of the "Windrush generation". This name comes from the ship Empire Windrush, which brought one of the first groups of West Indian migrants to the UK in 1948.

Besides those who were deported, many others were held, lost their jobs or homes, had their passports taken away, or were not allowed to get benefits or medical care they should have had. Some people who had lived in the UK for a long time were stopped from coming back into the country. Many more were threatened with immediate deportation by the Home Office.

Experts linked this scandal to the "hostile environment policy". This policy was started by Theresa May when she was in charge of the Home Office. The scandal led to Amber Rudd resigning as Home Secretary in April 2018. Sajid Javid then took over her job. The Windrush scandal also made people think more about Britain's immigration rules and how the Home Office works.

In March 2020, an independent report called the Windrush Lessons Learned Review was published. It was written by Wendy Williams, an inspector. The report said that the Home Office had shown "ignorance and thoughtlessness". It also said that what happened "could have been seen coming and avoided". The report found that immigration rules were made stricter "without thinking about the Windrush generation". Officials also asked for many documents in an "irrational" way to prove people's right to live in the UK.

A plan to pay compensation (money) to victims was announced in December 2018. However, by November 2021, only about 5% of victims had received any money. Sadly, 23 people who should have received payments died before they got anything. Three different groups of Members of Parliament (MPs) wrote reports in 2021. They criticized the Home Office for being too slow and not good enough at helping victims. They also asked for the compensation plan to be taken away from the Home Office.

Contents

- Why did the Windrush scandal happen?

- Were there warnings about the problem?

- What happened in Parliament?

- What did the National Audit Office say?

- Did deportations start again?

- How were victims helped?

- What happened to landing cards?

- How did Caribbean countries react?

- What did the Windrush Lessons Learned Review say?

- Sitting in Limbo

- See also

Why did the Windrush scandal happen?

The British Nationality Act 1948 gave everyone born in a British colony the right to be a citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies and live in the UK. This law, along with British government campaigns in Caribbean countries, encouraged many people to move to the UK.

Between 1948 and 1970, almost half a million people came from the Caribbean to Britain. In 1948, Britain needed many workers after the Second World War. These people who came to the UK around this time were later called the "Windrush generation". Adults who could work and many children traveled from the Caribbean. Some joined their parents or grandparents, while others came with their parents without their own passports.

These people had a legal right to come to the UK. They did not need or get any special documents when they arrived. This was also true after immigration laws changed in the early 1970s. Many worked or went to school in the UK without official records, just like any UK-born citizen.

Many of the countries these migrants came from became independent after 1948. This meant the migrants became citizens of their home countries. New laws in the 1960s and early 1970s limited the rights of citizens from these former colonies (now part of the Commonwealth) to come to or work in the UK.

However, anyone who arrived in the UK from a Commonwealth country before 1973 was automatically allowed to stay permanently. This was unless they left the UK for more than two years. Because this right was automatic, many people never received or were asked for proof of their right to stay. For the next forty years, they continued to live and work in the UK, believing they were British.

The Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 protected long-term residents from Commonwealth countries from being forced to leave. This protection was not included in the 2014 immigration laws. A Home Office spokesperson said this was because Commonwealth citizens living in the UK before 1 January 1973 were "protected enough" from being removed.

What was the "hostile environment" policy?

The "hostile environment policy" started in October 2012. It included rules and laws to make it very hard for people without permission to stay in the UK. The idea was that they might "leave on their own". In 2012, Theresa May, who was then the Home Secretary, said the goal was to create "a really hostile environment for illegal immigrants".

This policy was seen as a way to reduce immigration to the UK, as promised by the Conservative Party in 2010. It made landlords, employers, the NHS, charities, and banks check IDs. They had to refuse services to people who could not prove they had a legal right to live in the UK. Landlords and employers could be fined up to £10,000 if they did not follow these rules.

The policy made it harder to apply for permission to stay. It also encouraged people to leave the UK voluntarily. At the same time, the Home Office greatly increased fees for processing applications to stay, become a citizen, or register citizenship. The BBC reported that the Home Office made over £800 million in profit from nationality services between 2011 and 2017.

The term "hostile environment" was first used under the Gordon Brown Government. On 25 April 2018, during the Windrush scandal, Prime Minister Theresa May said the hostile environment policy would remain government policy.

In June 2020, Britain's human rights group, the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), started legal action. They wanted to review the "hostile environment" policy. They also wanted to see if the Home Office had followed its duties to treat everyone equally. In November 2020, the EHRC said the Home Office had broken the law. It had not thought about how its policies affected black members of the Windrush generation.

In August 2023, May said she regretted using the term 'hostile environment'. She blamed Clement Attlee and other Labour politicians for the Windrush scandal and the idea of the 'hostile environment'.

Were there warnings about the problem?

The Home Office received warnings from 2013 onwards. People said that many Windrush generation residents were being treated as illegal immigrants. They also warned that older Caribbean-born people were being targeted. The Refugee and Migrant Centre in Wolverhampton said their workers saw hundreds of people getting letters from Capita. Capita is a company that works for the Home Office. These letters told people they had no right to be in the UK. Some were told to arrange to leave the UK right away. About half of these letters went to people who already had permission to stay or were in the process of getting their immigration status sorted.

Workers had warned the Home Office directly and through local MPs about these cases since 2013. People considered illegal sometimes lost their jobs or homes because their benefits were stopped. Some were refused medical care by the National Health Service. Some were put in detention centres to prepare for deportation. Some were deported or not allowed to return to the UK from other countries.

In 2013, Caribbean leaders put the deportations on the agenda at the Commonwealth meeting in Sri Lanka. In April 2016, Caribbean governments told Philip Hammond, the UK Foreign Secretary, that people who had lived most of their lives in the UK were facing deportation. Their concerns were passed to the Home Office at that time.

Just before the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in April 2018, twelve Caribbean countries formally asked to meet the British Prime Minister to discuss the issue. Downing Street said no to this request.

What did Parliament say?

In January 2018, a group of MPs called the Home Affairs Select Committee wrote a report. It said that the hostile environment policies were "unclear". It also said that too many people were threatened with deportation based on "wrong and untested" information. The report warned that mistakes, sometimes 10% of cases, could make the whole system seem unreliable.

A big worry in the report was that the Home Office did not have a way to check if its hostile environment rules were working. It said there had been a "failure" to understand the effects of the policy. The report also noted that there wasn't enough accurate information about how many illegal immigrants there were. This allowed public worry about the issue to "grow unchecked". The report said this showed the government's "indifference" to a very important public issue.

A month before the report was published, over 60 MPs, university experts, and campaign groups wrote an open letter to Amber Rudd. They urged the Government to stop the "inhumane" policy. They pointed out the Home Office's "poor track record" of dealing with complaints and appeals quickly.

What did newspapers report?

From November 2017, newspapers reported that the British government had threatened to deport people from Commonwealth countries. These were people who had arrived in the UK before 1973 if they could not prove their right to stay. They were mainly called the "Windrush generation" and mostly came from the Caribbean. In April 2018, figures from the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford estimated that up to 57,000 Commonwealth migrants could be affected. Of these, 15,000 were from Jamaica. Besides those from the Caribbean, newspapers also found cases of people affected who were born in Kenya, Cyprus, Canada, and Sierra Leone.

Newspapers said that Home Office groups acted as if people were "guilty until proven innocent" and would "deport first, appeal later". They were accused of targeting the weakest groups, especially those from the Caribbean. They also said the rules were applied in an inhumane way. People's access to jobs, services, and bank accounts was cut off while their cases were still being checked.

The Home Office was also accused of losing many original documents that proved people's right to stay. They made unreasonable demands for proof. In some cases, elderly people were asked for four documents for every year they had lived in the UK. They also left people stuck outside the UK because of British administrative mistakes or stubbornness. Some were even denied medical treatment. Other cases in the news involved adults born in the UK whose parents were "Windrush" immigrants. These adults were threatened with deportation and lost their rights because they could not prove their parents were legally in the UK when they were born.

The Home Office and British government were also accused of knowing about the bad effects of the "hostile environment policy" on Windrush immigrants since 2013. But they had done nothing to fix the problems.

Journalists like Amelia Gentleman and Gary Younge helped bring attention to the issue. So did Caribbean diplomats Kevin Isaac, Seth George Ramocan, and Guy Hewitt. British politicians Herman Ouseley and David Lammy MP also spoke out. Amelia Gentleman from The Guardian newspaper won an award in 2018 for her reporting. The judges said she showed "the terrible consequences for a group of elderly Commonwealth-born citizens who were told they were illegal immigrants, even though they had lived in the UK for about 50 years".

What happened in Parliament?

In early March 2018, MPs started asking questions in Parliament about individual cases that had been in the news. On 14 March, Opposition Leader Jeremy Corbyn asked Theresa May about someone who had been refused medical treatment by the NHS. This happened during Prime Minister's Questions in the House of Commons. May first said she "didn't know about the case" but later agreed to "look into it". After this, Parliament continued to discuss what was increasingly called "the Windrush scandal".

On 16 April 2018, David Lammy MP challenged Amber Rudd in the House of Commons. He asked her for numbers of how many people had lost jobs or homes, been denied medical care, or been wrongly held or deported. Lammy asked Rudd to apologize for the deportation threats. He called it a "day of national shame" and blamed the problems on the government's "hostile environment policy". Rudd replied that she did not know of any such cases but would try to find out. In late April, more and more people called for Rudd to resign. They also wanted the Government to stop the "hostile environment policy". There were also calls for the Home Office to lower fees for immigration services.

On 2 May 2018, the opposition Labour Party put forward a motion in the House of Commons. They wanted to force the government to release documents to the Home Affairs Select Committee. These documents were about how the Home Office handled cases of people who came to the UK from Commonwealth countries between 1948 and the 1970s. The motion was defeated by 316 votes to 221.

Were there deportation targets?

On 25 April, Amber Rudd was asked by the Home Affairs Select Committee about deportation targets (meaning specific numbers of people to deport). Rudd said she did not know about such targets, saying "that's not how we operate". However, another person giving evidence had talked about deportation targets. The next day, Rudd admitted in Parliament that targets had existed. But she said they were only "local targets for internal performance management", not "specific removal targets". She also claimed she had not known about them and promised they would be stopped.

Two days later, The Guardian newspaper published a leaked memo. This memo had been sent to Rudd's office. It said that the department had set "a target of achieving 12,800 enforced returns in 2017–18". It also said "we have exceeded our target of assisted returns". The memo added that progress had been made towards "the 10% increased performance on enforced returns, which we promised the Home Secretary earlier this year". Rudd replied that she had never seen the leaked memo, "even though it was copied to my office, as many documents are".

The New Statesman magazine said the leaked memo gave "specific details of the targets set by the Home Office for the number of people to be removed from the United Kingdom. It suggests that Rudd misled MPs at least once". Diane Abbott MP called for Rudd to resign. She said: "Amber Rudd either failed to read this memo and has no clear understanding of the policies in her own department, or she has misled Parliament and the British people." Abbott also said, "The danger is that [the] very broad target put pressure on Home Office officials to bundle Jamaican grandmothers into detention centres".

On 29 April 2018, The Guardian published a private letter from Rudd to Theresa May, dated January 2017. In this letter, Rudd wrote about an "ambitious but achievable" target for increasing forced deportations of immigrants.

Who became the new Home Secretary?

Later that same day (29 April 2018), Rudd resigned as Home Secretary. In her resignation letter, she said she had "accidentally misled the Home Affairs Select Committee ... on the issue of illegal immigration". Later that day, Sajid Javid was named as her replacement.

Just before this, Javid, who was then the Communities Secretary, had said in a Sunday Telegraph interview: "I was really worried when I first started hearing and reading about some of the issues... My parents came to this country... just like the Windrush generation... When I heard about the Windrush issue I thought, 'That could be my mum, it could be my dad, it could be my uncle... it could be me.'"

On 30 April, Javid spoke in Parliament for the first time as Home Secretary. He promised new laws to protect the rights of those affected. He said the government would "do right by the Windrush generation". The press saw his comments as him trying to distance himself from Theresa May. Javid told Parliament that "I don't like the phrase hostile... I think it is a phrase that is unhelpful and it doesn't represent our values as a country".

On 15 May 2018, Javid told the Home Affairs Select Committee that 63 people had been identified as possibly wrongly deported. He said this number was not final and could go up. He also said he could not yet find out how many Windrush cases had been wrongly held.

By late May 2018, the government had contacted three of the 63 people possibly wrongly deported. On 8 June, Seth George Ramocan, the Jamaican high commissioner in London, said he still had not received the numbers or names of people the Home Office thought they had wrongly deported to Jamaica. This information was needed so Jamaican records could be checked for contact details. By late June, there were long delays in processing applications for "leave to remain". This was because many people were contacting the Home Office. The Windrush hotline had received 19,000 calls by that time. Of these, 6,800 were identified as possible Windrush cases. Sixteen hundred people had received documents after meeting with the Home Office.

After complaints from ministers, the Home Office was reported in April 2018 to have started an investigation. They wanted to find out where the leaked documents that led to Rudd's departure came from.

What did parliamentary committees say?

Human Rights committee report

On 29 June 2018, the parliamentary Human Rights Select committee published a "damning" report. It was about how immigration officials used their powers. MPs and peers in the report said there had been "systemic failures". They disagreed with the Home Office's description of "a series of mistakes", saying it was not "believable or enough". The report concluded that the Home Office showed a "completely wrong way of handling cases and taking away people's freedom". It urged the Home Secretary to act against the "human rights violations" happening in his department. The committee had looked at two cases where people had been held twice by the Home Office. The report called these detentions "simply unlawful" and their treatment "shocking". The committee wanted to examine 60 other cases.

Harriet Harman MP, who led the committee, accused immigration officials of being "out of control". She also said the Home Office was "a law unto itself". Harman commented that "protections and safeguards have been slowly removed until what we can see now... [is] that the Home Office is all powerful and human rights have been totally taken away." She added that "even when they're getting it wrong and even when all the evidence is there on their own files showing that they have no right to lock these people up, they go ahead and do it."

Home Affairs Select Committee report

On 3 July 2018, the HASC published another critical report. It said that unless the Home Office was completely changed, the scandal would "happen again, for another group of people". The report found that "a change in culture in the Home Office over recent years" had led to a situation where applicants were "forced to follow processes that seemed designed for them to fail". The report questioned if the hostile environment policy should continue as it was. It said that "renaming it as the 'compliant' environment is a meaningless response to real worries". (Sajid Javid had previously called the policy the 'compliant' environment policy).

The report suggested that the Home Office should re-check all hostile environment policies. They should look at how effective, fair, and costly they were, and what their effects were. This was because the policy put "a huge administrative burden and cost on many parts of society". There was no clear proof it worked, but many examples of mistakes and great distress caused.

The report made several suggestions to make the "Home Office seem more human". It also asked for "passport fees to be removed for Windrush citizens". It wanted a return to face-to-face immigration interviews. It also asked for immigration appeal rights and legal help to be brought back. Finally, it suggested that the target for net migration should be dropped.

The report said that they had hoped to find out how much the Windrush generation was affected. But the government "had not been able to answer many of our questions... and we have not had access to internal Home Office papers". It said it was "unacceptable that the Home Office still cannot tell us the number of people who have been unlawfully held, were told to report to Home Office centres, who lost their jobs, or were denied medical treatment or other services."

The report also suggested that the government's compensation plan should include "emotional distress as well as financial harm". It also said the plan should be open to Windrush children and grandchildren who had been badly affected. The report repeated its call for immediate financial help for those in serious financial trouble. Committee chair Yvette Cooper said the decision to delay hardship payments was "very troubling". She said victims "should not have to struggle with debts while they are waiting for the compensation scheme".

The report also stated that Home Office officials should have known about and dealt with the problem much earlier. MPs from different parties on the committee noted that the Home Office had done nothing for months while the issue was highlighted in the press.

The Labour Party responded to the report by saying that "many questions remained unanswered by the Home Office". Shadow Home Secretary Diane Abbott said it was a "disgrace" that the government had not yet published "a clear plan for compensation" for Windrush cases. She also said it had refused to set up a hardship fund, "even for people who have been made homeless or unemployed by their policies".

Home Office replies

The Home Office gave several replies during the scandal to questions from Parliamentary committees and in Parliament.

On 28 June 2018, a letter to the HASC from the Home Office reported that it had "mistakenly detained" 850 people between 2012 and 2017. In the same five-year period, the Home Office had paid over £21 million in compensation for wrongful detention. Compensation payments ranged from £1 to £120,000. It was not known how many of these detentions were Windrush cases. The letter also admitted that 23% of staff working in immigration enforcement had received performance bonuses. Some staff had "personal objectives" "linked to targets to achieve enforced removals" on which bonus payments were made.

Figures released on 5 June by immigration minister Caroline Nokes showed that in the 12 months before March 2018, the Home Office had booked 991 seats on commercial flights. These were to remove people to the Caribbean who were thought to be in the UK illegally. The 991 figure was not necessarily the number of deportations. Some removals might not have happened, and others might have involved multiple tickets for one person's flights. The figures did not say how many of the booked tickets were used for deportations. Nokes also said that between 2015 and 2017, the government spent £52 million on all deportation flights, including £17.7 million on special charter flights. Costs for the 12 months before March 2018 were not available.

In November 2018, in a monthly update to the Home Affairs Select Committee, Javid said that 83 cases had already been confirmed as wrongful deportations. Officials feared there might be another 81. At least 11 deported people had since died.

What did the National Audit Office say?

In a report published in December 2018, the UK's National Audit Office found that the Home Office "failed to protect [the] rights to live, work and access services" of the Windrush scandal victims. It had ignored warnings about the coming scandal, which were raised up to four years earlier. The office also said the Home Office had still not properly dealt with the scandal.

Did deportations start again?

Public anger against the deportations caused them to be stopped in 2018. However, in February 2019, it became clear that the Home Office planned to start deportations again. This news led to new public anger against the Home Office.

On 21 February 2019, the Jamaican High Commissioner to the UK asked for deportations to Jamaica to stop. He wanted them to wait until the Home Office had published its investigation into the Windrush scandal.

How were victims helped?

Amber Rudd, when she was still Home Secretary, apologized for the "terrible" treatment of the Windrush generation. On 23 April 2018, Rudd announced that those affected would receive compensation. Also, fees and language tests for citizenship applications would be removed for this group in the future. Theresa May also apologized for the "worry caused" at a meeting with 12 Caribbean leaders. However, she could not tell them "for sure" if anyone had been wrongly deported. May also promised that those affected would no longer need to rely on formal documents to prove their history of living in the UK. They also would not have to pay for necessary papers.

On 24 May, Sajid Javid, the new Home Secretary, explained several steps to process citizenship applications for people affected by the scandal. These steps included free citizenship applications for children who joined their parents in the UK when they were under 18. It also included free applications for children born in the UK to Windrush parents. And free confirmation of the right to stay for those who deserved it but were currently outside the UK, as long as they met normal good character rules.

MPs criticized these steps because they did not give people the right to appeal or review decisions. Yvette Cooper, who led the Commons Home Affairs Committee, said: "Given what has happened, how can anyone trust the Home Office not to make more mistakes? If the Home Secretary is sure that senior caseworkers will make good decisions in Windrush cases, he has nothing to fear about appeals and reviews." Javid also said that a Home Office team had found 500 possible cases so far.

In the weeks that followed, Javid also promised to provide numbers on how many people had been wrongly held. He also said he did not believe in specific targets for removals.

On 21 May 2018, it was reported that many Windrush victims were still very poor. Some were sleeping on the streets or on friends' sofas while waiting for the Home Office to act. Many could not afford to travel to Home Office appointments if they got them. David Lammy MP said it was "yet another failure in a long list of complete failures that Windrush citizens are being left homeless and hungry on the streets." In late May and early June, MPs called for a hardship fund to be set up to help with urgent needs. By late June, it was reported that the government's two-week deadline for solving cases had been missed many times. Many of the most serious cases still had not been dealt with. Jamaican High Commissioner Seth George Ramocan said: "There has been an effort to correct the situation now that it has become so very open and public."

In August 2018, a compensation plan had still not been put into action. Examples included a man who was still homeless while waiting for a decision. A former NHS nurse, Sharon, told a caseworker, "I am not allowed to work, I have no benefits. I have a 12-year-old child." The caseworker replied, "Well I'm afraid these are the immigration rules... but obviously the Home Office point of view [is] if you don't have a legal status in the UK you're not entitled to work or study." Satbir Singh from the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants said: "It's terrible that the Home Office effectively told Sharon to go and beg for food. This is when there are laws requiring the state to act in the best interests of children, and provide financial support to children facing extreme poverty." Also in August 2018, a caseworker for David Lammy said: "We have sent 25 people from our area to the Windrush taskforce in total. Only three have been granted their citizenship so far, and the others are left in a strange waiting state... We still have some people who have not even got biometric residence permits and we told the Home Office about these people months ago."

What about hardship and compensation payments?

In February 2019, the Home Office admitted that it had set up a hardship plan in December 2018 for victims of the scandal. However, only one person who applied had received any help so far. Also, the compensation plan promised by the Home Office in April 2018 was still not in place in February 2019.

In February 2020, government ministers were told that the number of people wrongly called illegal immigrants could be much higher than thought. As many as 15,000 people could be able to get compensation. Despite this, only 36 people's compensation claims had been settled so far. Only £62,198 had been paid out from a Home Office compensation fund that was expected to give out between £200 million and £570 million.

By April 2020, the Windrush taskforce, which was set up to deal with applications from people wrongly called illegal immigrants, still had 3,720 cases waiting. Of these, 1,111 cases had not yet been looked at. Over 150 cases had waited for more than six months, and 35 had waited for longer than a year for a reply. The Home Office said it had identified 164 people from Caribbean countries whom it had wrongly held or deported. Twenty-four people who had been wrongly deported had died before the UK government could contact them. Fourteen people wrongly deported to the Caribbean had not yet been found. Officials refused to try to find people who had been wrongly deported to other Commonwealth countries outside the Caribbean. Up to that date, 35 people had been given "urgent and exceptional support" payments, totaling £46,795.

By October 2020, nine victims had died without receiving their compensation. Many others had yet to receive compensation.

In November 2021, a report from the cross-party Home Affairs Select Committee found that at least 23 victims had died without receiving compensation. Only about 5% of Windrush victims had received compensation. The Home Office first thought about 15,000 people would be eligible. But by the end of September 2021, only 864 people had received any compensation. The Home Affairs Committee report found "many flaws in the design and operation" of the compensation plan. These included making claimants provide too much proof of their losses. There were also long delays in processing applications and making payments. The plan did not have enough staff, and it failed to provide urgent payments to those in desperate need. The report noted it was "staggering" that the Home Office had not prepared, funded, and staffed the Windrush compensation plan before it started.

Other reports in 2021 from the National Audit Office, the Public Accounts Committee, and the legal charity JUSTICE all criticized how slow and ineffective the compensation plan was. They recommended that the plan be taken away from the Home Office.

In June 2022, Home Office figures showed that 7% of its original expected 15,000 claimants, and 25% of actual claimants, had received any compensation by that date. Another 25% of claims had been processed and rejected.

In April 2023, Human Rights Watch reported that the compensation plan was still failing victims. Human Rights Watch said there was a strong agreement among victims that the plan "was designed to fail the people who were supposed to benefit from it."

What happened to landing cards?

The only official records of many "Windrush" immigrants arriving in the 1950s and early 1970s were landing cards. These cards were collected when people got off ships in UK ports. For many years, British immigration officials used these cards to check arrival dates for difficult immigration cases. In 2009, these landing cards were chosen to be destroyed as part of a bigger clean-up of paper records. The decision to destroy them was made under the Labour government at the time. But it was carried out in 2010 under the new coalition government. People who reported problems and retired immigration officers said they had warned managers in 2010 that this would cause problems for some immigrants who had no other record of their arrival. During the scandal, there was discussion about whether destroying the landing cards had a negative effect on Windrush immigrants.

How did Caribbean countries react?

- Antigua and Barbuda: Prime Minister Gaston Browne told Sky News that an apology from the British government about the Windrush issue "would be welcome". He said it had been a big worry, but he was happy the government had stepped in. "We have had at least one Antiguan who also has a British passport. He was apparently identified for deportation because he had no original documents. He came here about 59 years ago as a baby with his parents, and would have been on his parents' passport. Many of these people have no connection with the country where they were born. They would have lived in the UK their entire lives and worked very hard to help the UK."

- Barbados: High Commissioner the Rev. Guy Hewitt said on 16 April that the "Windrush Kids" who went to schools in Britain and paid their taxes were being "treated as illegal immigrants". They were "shut out of the system", with some deported or sent to detention centres. Hewitt also advised people not to contact the Home Office unless they first told their representative or lawyer. This was because too many people who did so had been held. During interviews in March 2021, Hewitt talked about the scandal. He said it was time to move away from an "oppressive and racist colonial past". In Hewitt's view, many believe that the "monarchy symbolizes part of that historic oppression". He also said the country was due for "a native born citizen as head of state".

- Grenada: Prime Minister Keith Mitchell said that those affected were owed "serious compensation".

- Jamaica: Prime Minister Andrew Holness said on 18 April: "my interest is to make sure that the Windrush generation and their children get justice. We have to call it out for what it is. But we also have to make sure that those who have been deported get a way to come back. They should get all the benefits that their citizenship will give them. If it was agreed that a wrong was done, then there should be a process of putting things right. I am sure that the strong civil society and democracy you have will come up with a process of compensation."

- Saint Kitts and Nevis: High Commissioner Kevin Isaac helped Caribbean high commissioners work together to speak with one voice on the Windrush issue from 2014.

What did the Windrush Lessons Learned Review say?

On 19 March 2020, the Home Office released the Windrush Lessons Learned Review. This study, which the Home Secretary called "long-awaited", was an independent investigation. It was managed and carried out by Wendy Williams, an inspector. The report concluded that the Home Office showed "inexcusable ignorance and thoughtlessness". It also said that what happened "could have been seen coming and avoided". It further found that immigration rules were made stricter "with complete disregard for the Windrush generation". Officials had also made "irrational" demands for many documents to prove people's right to live in the UK. The study suggested a full review of the "hostile environment" immigration policy.

In March 2022, a progress report on the Learned Review said that the Home Office had broken promises to change its culture after the Windrush inquiry. It warned that the scandal could happen again. The report also criticized the failure to check how effective the hostile environment policies were (now called "compliant environment" policies). It also criticized how slow the compensation plan was. A small survey of people who applied for compensation found that 97% did not trust the Home Office to keep its promises.

Sitting in Limbo

In June 2020, BBC Television showed an 85-minute TV drama called Sitting in Limbo. It starred Patrick Robinson as Anthony Bryan, who was affected by the hostile environment policy.

See also

- Dexter Bristol, a man from Grenada who died in poverty after losing his job because of the Home Office hostile environment policy.

- Paulette Wilson, one of the first cases covered in British media. She later became an activist helping other victims of the scandal.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |