HMT Empire Windrush facts for kids

class="infobox " style="float: right; clear: right; width: 315px; border-spacing: 2px; text-align: left; font-size: 90%;"

| colspan="2" style="text-align: center; font-size: 90%; line-height: 1.5em;" |

|}

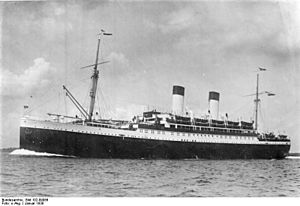

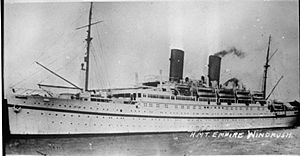

The HMT Empire Windrush, originally named MV Monte Rosa, was a large passenger ship. She was built in Germany in 1930. "MV" means "Motor Vessel" and "HMT" means "His Majesty's Transport".

First, the German company Hamburg Süd owned and operated her as the Monte Rosa. During World War II, the German navy used her as a troopship. After the war, the British Government took her. They renamed her the Empire Windrush.

The ship continued to serve as a troopship for the British until March 1954. Sadly, she caught fire and sank in the Mediterranean Sea. Four crew members lost their lives.

In 1948, the Empire Windrush became famous. She carried a large group of people from the British West Indies (Caribbean islands) to the United Kingdom. There were 1,027 passengers and two stowaways on board. Most of them wanted to settle in the UK.

While other ships also brought Caribbean people to the UK, the Windrush's 1948 journey is very well-known. People who came to the UK from the Caribbean after World War II are often called the Windrush generation.

Contents

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | MV Monte Rosa (1930–1947) |

| Namesake | Monte Rosa |

| Owner |

|

| Operator |

|

| Port of registry | Hamburg (1930–40) |

| Builder | Blohm & Voss, Hamburg |

| Yard number | 492 |

| Launched | 13 December 1930 |

| Maiden voyage | 28 March 1931–30 June 1931, Hamburg – South America – Hamburg |

| Out of service | 1945 |

| Identification | |

| Fate | Seized by the United Kingdom as a war reparation |

| Name | HMT Empire Windrush |

| Namesake | River Windrush |

| Owner |

|

| Operator | New Zealand Shipping Company |

| Port of registry | London |

| Acquired | 1945 |

| In service | 1947 |

| Out of service | 30 March 1954 |

| Fate | Sank after catching fire |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage |

|

| Length | 500 ft 3 in (152.48 m) |

| Beam | 65 ft 7 in (19.99 m) |

| Depth | 37 ft 8 in (11.48 m) |

| Propulsion | 4 SCSA diesel engines (Blohm & Voss, Hamburg), double reduction geared driving two propellers. |

| Speed | 14.5 knots (26.9 km/h) |

Ship's History and Design

The Empire Windrush, originally called MV Monte Rosa, was one of five similar ships. These ships were known as the Monte-class. They were built in Hamburg, Germany, by Blohm & Voss between 1924 and 1931.

In the 1920s, Hamburg Süd hoped to carry many German people moving to South America. The first two ships were built for this purpose. However, fewer people moved than expected. So, the ships were changed into cruise ships. They offered trips in Europe and South America.

This idea was a big success! Before this, only rich people could go on cruises. But Hamburg Süd offered cruises at lower prices. This allowed many more people to enjoy sea holidays. Another ship, the Monte Cervantes, was built because of this success. Sadly, she hit a hidden rock and sank after only two years. Despite this, the company ordered two more ships: the Monte Pascoal and the Monte Rosa.

The Monte Rosa was about 152 meters (500 feet) long. She was about 20 meters (65 feet) wide. Her depth was about 11.5 meters (37 feet).

How the Ship Got Its Name

The Monte-Class ships were named after mountains. Monte Rosa was named after Monte Rosa, a tall mountain on the border of Switzerland and Italy. It is the second-highest mountain in the Alps.

When the ship joined British service, her name changed. Merchant ships used by the United Kingdom Government during and after World War 2 were often called "Empire" ships. There were about 1,300 such ships. The Empire Windrush was one of about sixty "Empire" ships named after British rivers. The River Windrush is a small river that flows into the Thames near Oxford.

The ship's official identification also changed. It went from "MV" (Motor Vessel) to "HMT". This prefix was used for British troopships. It could mean "His Majesty's Troopship" or "His Majesty's Transport".

Final Journey and Sinking

The Empire Windrush began her last trip from Yokohama, Japan, in February 1954. She was heading to the United Kingdom. Along the way, she stopped at places like Hong Kong, Singapore, and Port Said. Her passengers included soldiers who had been hurt in the Korean War.

However, the journey had many problems. The engines often broke down. There was even a fire after leaving Hong Kong. It took 10 weeks to reach Port Said. From there, the ship sailed with 222 crew members and 1,276 passengers. This included soldiers, women, and children. The ship was almost full.

Fire on Board

Early on Sunday, March 28, a sudden explosion happened in the engine room. A fierce fire started. Four crew members in the engine room died. The ship was in the western Mediterranean Sea, near Algeria.

The fire quickly caused the ship to lose all electrical power. The emergency generator started, but its power could not be used for the main systems. It only powered emergency lights and the radio.

The ship did not have a sprinkler system. The firefighting team tried to put out the fire. But they could only work for a few minutes. The loss of electricity stopped the water pumps for their hoses. Attempts to close watertight doors from the bridge also failed.

Amazing Rescue Operations

At 6:23 AM, the ship sent out distress calls. The order was given to wake everyone up. But the ship's public address system was not working. So, the crew had to tell everyone by shouting.

At 6:45 AM, all efforts to fight the fire stopped. The order was given to launch the lifeboats. The first boats carried the women and children, and even the ship's cat!

The ship had 22 lifeboats, enough for everyone. But thick smoke and no electricity made it hard to launch them. Only 12 lifeboats were successfully launched. Many crew and troops climbed down ropes or jumped into the sea. They were picked up by the Windrush's lifeboats or by other rescue ships.

The last person left the Windrush at 7:30 AM. Even though some people were in the sea for two hours, everyone was rescued. The only people who died were the four crew members killed in the engine room.

Several ships came to help, including the Dutch ship Mentor and the British ship Socotra. A Royal Air Force plane also helped. The rescued people were taken to Algiers. From there, they went to Gibraltar and then flew back to the United Kingdom.

Salvage Attempt and Sinking

About 26 hours after the Empire Windrush was abandoned, a Royal Navy ship, HMS Saintes, reached her. The fire was still burning. A team from the Saintes got on board and attached a tow cable.

The Saintes began to tow the burning ship towards Gibraltar. But the Empire Windrush sank in the early hours of Tuesday, March 30, 1954. She had only been towed about 16 kilometers (10 miles). The wreck now lies about 2,600 meters (8,500 feet) deep.

Lasting Impact

In 1954, some military personnel on the Empire Windrush received awards for their bravery during the evacuation. A military nurse was honored for helping patients escape the burning ship.

In 1998, a public space in Brixton, London, was renamed Windrush Square. This was to remember the 50th anniversary of the Caribbean passengers' arrival. In 2008, a plaque was put up at the Port of Tilbury to honor the "Windrush Generation."

The ship's story was also briefly shown in the Opening Ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics. A small model of the ship covered in newspaper was part of the show. In 2020, people started raising money to recover one of the ship's anchors. This anchor would become a monument to the Windrush generation.

Images for kids