Mary Seacole facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mary Jane Seacole

|

|

|---|---|

A portrait of Seacole (c. 1850)

|

|

| Born |

Mary Jane Grant

23 November 1805 Kingston, Colony of Jamaica

|

| Died | 14 May 1881 (aged 75) Paddington, London, United Kingdom

|

| Other names | Mother Seacole |

| Citizenship | British |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Assistance to sick and wounded military personnel during Crimean War |

| Honours | Order of Merit (Jamaica) |

Mary Jane Seacole (born Grant; 23 November 1805 – 14 May 1881) was a brave British-Jamaican nurse and businesswoman. She became famous for helping soldiers during the Crimean War. She set up a place called the "British Hotel" near the battlefield. This hotel was a place where sick and injured officers could rest and eat.

Mary Seacole came from a family of Jamaican and West African "doctresses." These were women healers who used traditional herbal medicines. She showed great kindness, skill, and courage while caring for soldiers. She was given the Jamaican Order of Merit award in 1991, after her death. In 2004, she was voted the greatest black Briton in a public survey.

When the Crimean War started, Mary Seacole wanted to help nurse the wounded. She asked the War Office in Britain if she could join the nurses going to the war. But her offer was turned down. So, she decided to travel on her own and set up her hotel. She became very popular with the soldiers. After the war, when she had money problems, the soldiers even raised money to help her.

For almost 100 years after her death, many people forgot about her. But then, her amazing work started to be recognized. Her book, Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands (1857), is one of the first books written by a black woman from the Caribbean. In 2016, a statue of her was put up at St Thomas' Hospital in London. It calls her a "pioneer," meaning someone who leads the way.

Contents

- Mary Seacole's Early Life and Training

- Adventures in the Caribbean (1826–1851)

- Helping People in Central America (1851–1854)

- Mary Seacole and the Crimean War (1853–1856)

- Life Back in London (1856–1860)

- Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands

- Later Life and Recognition

- How Mary Seacole is Remembered

- See also

Mary Seacole's Early Life and Training

Mary Jane Grant was born on November 23, 1805, in Kingston, Jamaica. Her mother, Mrs. Grant, was a healer known as "The Doctress." She used traditional Caribbean and African herbal medicines. Mary's father, James Grant, was a Scottish Lieutenant in the British Army.

Mary learned her nursing skills at her mother's boarding house, Blundell Hall. This house also served as a place for soldiers to recover from illnesses. Mary learned about cleanliness, fresh air, warmth, good food, and caring for people who were very sick. She started by practicing on her doll and pets. Then she helped her mother treat people.

Because her family was close to the army, she also learned from military doctors. She combined this knowledge with the West African remedies from her mother. Mary was proud of her Jamaican and Scottish background. She called herself a Creole. In her book, she wrote that she had "good Scots blood" and was proud of her "deeper brown" skin.

Mary Seacole also spent some time living with an older woman she called her "kind patroness." She was treated like family and received a good education. As the educated daughter of a Scottish officer and a free black businesswoman, Mary had a respected place in Jamaican society.

Around 1821, Mary visited London for a year. She noticed that her darker-skinned West Indian friend was teased by children. Mary herself was "only a little brown." She returned to London later to sell West Indian foods. Her later travels were done without a chaperone, which was very unusual for women at that time.

Adventures in the Caribbean (1826–1851)

After returning to Jamaica, Mary helped care for her patroness until she passed away. Then, Mary worked with her mother at Blundell Hall. Sometimes, she was called to help at the British Army hospital at Up-Park Camp. She also traveled around the Caribbean. She visited places like The Bahamas, Cuba, and Haiti.

On November 10, 1836, she married Edwin Horatio Hamilton Seacole in Kingston. Edwin was a merchant, but he often got sick. They tried to open a store in Black River, but it didn't do well. They moved back to Blundell Hall in the early 1840s.

In 1843 and 1844, Mary faced tough times. Blundell Hall burned down in a fire, but a new, better one was built. Then, her husband died in October 1844, and her mother passed away soon after. After a time of sadness, Mary took over running her mother's hotel. She said her "hot Creole blood" helped her recover quickly.

Mary focused on her work and turned down many marriage offers. She became well-known to European military visitors who stayed at Blundell Hall. In 1850, she helped treat people during a serious cholera outbreak in Jamaica.

Helping People in Central America (1851–1854)

In 1850, Mary's half-brother Edward moved to Cruces, Panama. He opened a hotel there for travelers crossing between the east and west coasts of the United States. Many people were traveling because of the 1849 California Gold Rush.

In 1851, Mary visited her brother in Cruces. Soon after she arrived, a cholera outbreak hit the town. Mary was there to treat the first person who got sick, and that person survived. This made Mary famous, and many more patients came to her. She treated the poor for free. She used mustard rubs, poultices, and gave patients boiled water with cinnamon to help them stay hydrated.

Mary even performed an autopsy on a child she had cared for. This helped her learn more about the disease. She herself got cholera but recovered after a few weeks. She wrote that the people of Cruces showed her much sympathy.

Cholera returned in 1852. Even Ulysses S. Grant, who later became a U.S. President, passed through Cruces and lost many men to the disease.

Mary saw a chance to start a business. She opened the British Hotel, which was more of a restaurant. She described it as a "tumble down hut" with two rooms. She also added a barber service.

Mary noticed that escaped African-American slaves held important jobs in Panama. She saw that "freedom and equality elevate men." She also noticed tension between Panamanians and Americans.

In 1853, Mary returned to Jamaica. She faced racism when trying to book a ship to go home. She was asked by Jamaican doctors to help with a severe yellow fever outbreak. She did her best, but the disease was very strong. In Cuba, people remembered her as "the Yellow Woman from Jamaica with the cholera medicine."

In early 1854, Mary went back to Panama to finish her business. She read newspaper reports about the war starting against Russia. This was the Crimean War. She decided to travel to England to volunteer as a nurse. She wanted to use her herbal healing skills to help the soldiers. She knew some of the soldiers who were going to Crimea, as she had cared for them before.

Mary Seacole and the Crimean War (1853–1856)

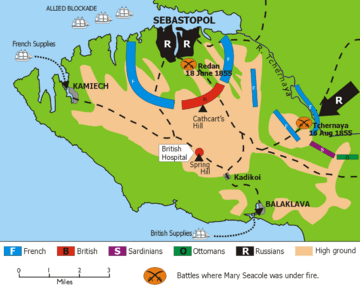

The Crimean War was fought from 1853 to 1856. It was between the Russian Empire and an alliance of Britain, France, Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire. Most of the fighting happened in Crimea, near the Black Sea.

Thousands of soldiers got sick, mostly from cholera. Many died before even reaching the hospitals. The hospitals were crowded and dirty. In Britain, a newspaper article led to Florence Nightingale being asked to lead a group of nurses to Turkey. She left on October 21.

Mary Seacole traveled from Panama to England. She tried to join the nurses going to Crimea, but she was refused by the War Office. She wrote that she had "ample testimony" of her nursing experience. She wondered if racism was why she was turned down. She wrote, "Was it possible that American prejudices against colour had some root here?" She also tried to join Miss Nightingale's group but was told there were no openings.

Mary decided to go to Crimea on her own. She planned to open the British Hotel. Her friend, Thomas Day, joined her. They bought supplies, and Mary sailed to Constantinople in January 1855. In Malta, she met a doctor who gave her a letter to Florence Nightingale.

Mary visited Nightingale at the Barrack Hospital in Scutari. She asked for a bed for the night. Mary said her meeting with Nightingale was friendly. Nightingale asked if she needed anything. Mary explained she was going to Balaclava to join her business partner. She was given a bed for the night.

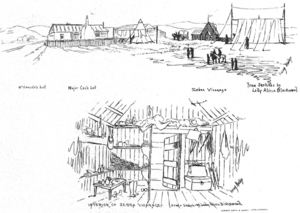

Mary found a spot for her hotel near Balaclava, close to the British headquarters. She built the hotel using salvaged wood, metal, and old windows. The new British Hotel opened in March 1855. Alexis Soyer, a famous French chef, visited her. He described Mary as "an old dame of a jovial appearance." He advised her to focus on food and drinks, not beds.

The hotel was finished in July, costing £800. It had a main room, a kitchen, and two sleeping huts. Mary sold everything from "a needle to an anchor" to officers and visitors. Two black cooks prepared meals.

Mary's business did well, even with constant thefts. She often cooked herself. She also "dispensed medications" when needed. Soyer often visited and praised her food.

Mary often went to the troops as a sutler, selling supplies near the British camp. She also nursed wounded soldiers from the trenches. The British Army knew her as "Mother Seacole."

She also provided food for people watching the battles. She spent time on Cathcart's Hill, observing. Once, while helping wounded troops under fire, she hurt her thumb. William Howard Russell, a reporter for The Times, wrote that she was a "warm and successful physician." He said she was "always in attendance near the battlefield to aid the wounded."

Mary wore bright, noticeable clothes, often blue or yellow. Lady Alicia Blackwood remembered that Mary "personally spared no pains" to help the suffering. She gave freely to those who couldn't pay.

One British medical officer said Mary was "a celebrated person." He noted she supplied hot tea to wounded men waiting for transport. He said she didn't spare herself, working "in rain and snow" to brew tea. Mary also carried bandages, needles, and thread to treat wounds.

In September 1855, Mary was there for the final attack on Sevastopol. After the city fell, she became the first British woman to enter Sevastopol. She toured the damaged town, bringing refreshments and visiting the hospital. She even took some items from the city, like a church bell.

After Sevastopol fell, Mary and Day's business continued to do well. Officers enjoyed themselves with theatrical shows and horse races. Mary provided catering for these events.

Mary was joined by a 14-year-old girl named Sarah, also called Sally. Chef Soyer described her as "the Egyptian beauty, Mrs Seacole's daughter Sarah."

Peace talks began in Paris in early 1856. The Treaty of Paris was signed on March 30, 1856. Soldiers then left Crimea. Mary faced financial problems. She had many unsold supplies and creditors demanding payment. She tried to sell her goods but had to auction them for low prices.

Mary was one of the last to leave Crimea. She returned to England "poorer than [she] left it." But her impact on the soldiers was huge. The Illustrated London News wrote that "Mother Seacole was a household word in the camp."

Some historians, like Lynn McDonald, believe Mary Seacole's role has been exaggerated. McDonald says Mary was kind and generous, but her "tea and lemonade did not save lives." However, other historians argue that Mary's experience was greater than Florence Nightingale's. They point out that Mary prepared medicines, diagnosed illnesses, and performed minor surgery. William Howard Russell praised Mary's skill as a healer.

Life Back in London (1856–1860)

After the war, Mary returned to England with little money and poor health. She tried to open a canteen, but it failed. She attended a celebration for soldiers where Florence Nightingale was the main guest. Mary was also cheered by the crowds.

However, Mary had many debts. She was declared bankrupt on November 7, 1856. Her business partner, Day, may have caused some of her financial problems.

Around this time, Mary started wearing military medals. A sculpture of her from 1871 shows her wearing four medals. These included the British Crimea Medal, the French Légion d'honneur, and the Turkish Order of the Medjidie. It's thought she may have bought these medals to show her support for the army.

The British newspapers wrote about Mary's money troubles. People started a fund to help her. Many important people donated. In January 1857, she was cleared of bankruptcy. Day left for other countries, but Mary still had little money. She moved to cheaper rooms in Soho Square.

In May 1857, Mary wanted to go to India to help wounded soldiers there. But she was advised not to because of her money problems. A big fundraising event called the "Seacole Fund Grand Military Festival" was held in July 1857. Many military men supported it. Over 1,000 artists performed, and about 40,000 people attended. However, the company running the event went bankrupt, and Mary only received a small amount of money.

Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands

Mary Seacole's 200-page autobiography was published in July 1857. It was called Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands. This was the first autobiography written by a black woman in Britain. The book cost one shilling and six pence. It had a striking portrait of Mary on the cover.

It is thought that Mary told her story to an editor, who helped her write it down. In the book, she spends a short chapter on her first 39 years. Then she writes six chapters about her time in Panama. The next 12 chapters are about her adventures in Crimea. She doesn't mention her parents' names or her exact birth date. She talks about how she first practiced medicine on animals.

Mary also shares how she was poor after the Crimean War, while others in her position became rich. She describes the respect she gained from the soldiers, who called her "mother." The book ends with her return to England and lists people who supported her. The book was dedicated to Major-General Lord Rokeby. In the introduction, the Times reporter William Howard Russell wrote, "I have witnessed her devotion and her courage... and I trust that England will never forget one who has nursed her sick."

The Illustrated London News praised her book. In 2017, Robert McCrum called it "gloriously entertaining."

Later Life and Recognition

Around 1860, Mary Seacole joined the Roman Catholic Church. She returned to Jamaica, which had changed. By 1867, she needed money again. The Seacole fund was started again in London. New supporters included the Prince of Wales and other important military officers. The fund grew, and Mary was able to buy land in Kingston, Jamaica. She built a new home there and a property to rent out.

By 1870, Mary was back in London. She became a personal masseuse to the Princess of Wales. Prince Victor of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, a nephew of Queen Victoria, carved a marble bust of her in 1871. He had been one of her customers in Crimea.

Mary Seacole died on May 14, 1881, in Paddington, London. She left behind more than £2,500. She was buried in St. Mary's Roman Catholic Cemetery, Kensal Green, London.

How Mary Seacole is Remembered

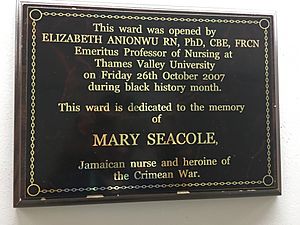

After her death, Mary Seacole was largely forgotten in Britain for almost a century. But she was better remembered in Jamaica. In the 1950s, buildings were named after her, like "Mary Seacole House" for nurses. A hall at the University of the West Indies and a hospital ward were also named in her honor. In 1990, she was given the Jamaican Order of Merit after her death.

Her grave in London was found again in 1973. A service was held, and her gravestone was restored. The Mary Seacole Memorial Association was founded in 1980 to keep her memory alive. An English Heritage blue plaque was put up at one of her former homes in London in 1985. Another blue plaque was placed at 14 Soho Square, where she lived in 1857.

By the 21st century, Mary Seacole became much more famous. Many health care buildings and organizations are now named after her. In 2007, her life story was added to the National Curriculum in UK schools.

In 2004, she was voted first in an online poll of 100 Great Black Britons. Her portrait was used on a first-class stamp in 2005.

The Mary Seacole Centre for Nursing Practice at Thames Valley University is named after her. There is also a Mary Seacole Research Centre at De Montfort University. New buildings at the University of Salford and Birmingham City University also bear her name. There are Mary Seacole wards in hospitals, and a Mary Seacole Nursing Home. The NHS Seacole Centre in Surrey opened in 2020 to help patients recovering from Covid-19.

An annual award for leadership in nursing is named Seacole. The NHS Leadership Academy has a six-month leadership course called the Mary Seacole Programme. An exhibition celebrating her birth opened at the Florence Nightingale Museum in London in 2005 and was very popular.

A campaign to build a statue of Seacole in London started in 2003. The statue, designed by Martin Jennings, was unveiled on June 30, 2016, at St Thomas' Hospital. The words from William Howard Russell's 1857 article are on the statue: "I trust that England will not forget one who nursed her sick, who sought out her wounded to aid and succour them."

A movie about her life was planned in 2019. Mary Seacole is also featured in the BBC show Horrible Histories. In 2016, Google celebrated her with a Google Doodle.

See also

In Spanish: Mary Seacole para niños

In Spanish: Mary Seacole para niños

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |