Iain Macleod facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Iain Macleod

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

| In office 20 June 1970 – 20 July 1970 |

|

| Prime Minister | Edward Heath |

| Preceded by | Roy Jenkins |

| Succeeded by | Anthony Barber |

| Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

| In office 11 November 1965 – 20 June 1970 |

|

| Leader | Edward Heath |

| Preceded by | Edward Heath |

| Succeeded by | Roy Jenkins |

| Leader of the House of Commons | |

| In office 9 October 1961 – 20 October 1963 |

|

| Prime Minister | Harold Macmillan |

| Preceded by | Rab Butler |

| Succeeded by | Selwyn Lloyd |

| Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster | |

| In office 9 October 1961 – 20 October 1963 |

|

| Prime Minister | Harold Macmillan |

| Preceded by | Charles Hill |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Blakenham |

| Chairman of the Conservative Party | |

| In office 9 October 1961 – 20 October 1963 |

|

| Leader | Harold Macmillan |

| Preceded by | Rab Butler |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Blakenham |

| Secretary of State for the Colonies | |

| In office 14 October 1959 – 9 October 1961 |

|

| Prime Minister | Harold Macmillan |

| Preceded by | Alan Lennox-Boyd |

| Succeeded by | Reginald Maudling |

| Minister of Labour and National Service | |

| In office 20 December 1955 – 14 October 1959 |

|

| Prime Minister | Anthony Eden Harold Macmillan |

| Preceded by | Walter Monckton |

| Succeeded by | Edward Heath |

| Minister of Health | |

| In office 7 May 1952 – 20 December 1955 |

|

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill Anthony Eden |

| Preceded by | Harry Crookshank |

| Succeeded by | Robin Turton |

| Member of Parliament for Enfield West |

|

| In office 23 February 1950 – 20 July 1970 |

|

| Preceded by | Ernest Davies (Enfield) |

| Succeeded by | Cecil Parkinson |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Iain Norman Macleod

11 November 1913 Skipton, United Kingdom |

| Died | 20 July 1970 (aged 56) London, United Kingdom |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse |

Evelyn Blois

(m. 1941) |

| Children | 2 |

| Alma mater | Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge |

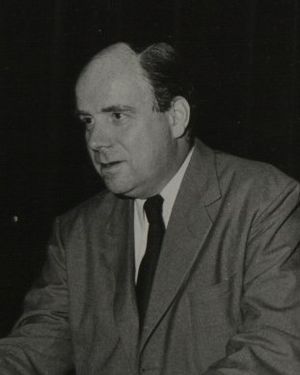

Iain Norman Macleod (born 1913, died 1970) was an important British politician. He was a member of the Conservative Party.

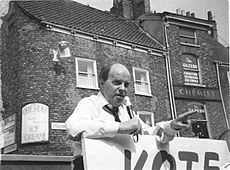

Before becoming a politician, he was a skilled bridge player. After serving in World War II, he worked for the Conservative Party's research team. He became a Member of Parliament (MP) in 1950. He was known for being a very strong speaker in Parliament and at public events.

He quickly became the Minister of Health, and later the Minister of Labour. He then served as Secretary of State for the Colonies under Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. In this role, he helped many African countries gain independence from British rule. This made some people in his own party unhappy.

In 1963, Macleod refused to join the government of the new Prime Minister, Alec Douglas-Home. He felt the way the new leader was chosen was unfair. He then became the editor of The Spectator magazine.

Macleod supported Edward Heath in the 1965 Conservative Party leadership election. When the Conservatives won the election in June 1970, Macleod was made Chancellor of the Exchequer. This is the minister in charge of the country's money. Sadly, he died suddenly just one month later.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Iain Macleod was born in Skipton, Yorkshire, on 11 November 1913. His father, Dr. Norman Alexander Macleod, was a respected doctor. Iain often went with his father on his rounds to visit patients. His parents were from the Isle of Lewis in Scotland. They moved to Skipton in 1907. Macleod felt a strong connection to Scotland. His parents bought land on the Isle of Lewis in 1917, where they spent family holidays.

He went to Ermysted's Grammar School in Skipton. Then he attended St Ninian's Dumfriesshire and Fettes College in Edinburgh. He wasn't a top student, but he loved literature, especially poetry. He read and memorized many poems.

Cambridge University and Bridge Playing

In 1932, Macleod went to Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. He studied History there. He didn't get involved much in student politics. Instead, he spent a lot of time reading poetry and playing bridge. He even helped start the Cambridge University Bridge Society. He finished his degree in 1935.

After university, he got a job offer at a printing company called De La Rue. But he spent most of his energy on bridge. By 1936, he was an international bridge player. He was one of Britain's best bridge players. He won the Gold Cup in 1937 with his team.

He sometimes won a lot of money playing cards at night. This meant he was often tired for work in the mornings. After a few years, De La Rue let him go in 1938. To please his father, he started studying to become a barrister (a type of lawyer). But in the late 1930s, he mostly earned money from playing bridge. He could earn a lot, tax-free.

In 1952, he published a book about bridge called Bridge is an Easy Game. He continued to earn money from playing and writing about bridge until his political career became his main focus.

War Service in World War II

Joining the Army

In September 1939, when World War II began, Macleod joined the British Army. He started as a private soldier. In April 1940, he became an officer in the Duke of Wellington's Regiment. His battalion was sent to France. He was injured in the leg during the Battle of France in May. He had a slight limp for the rest of his life. He also suffered from a painful spinal condition.

After recovering, he worked as a staff captain. In 1941, he had a strange incident with a fellow officer, Captain Dawtry. Macleod shot at Dawtry's door after Dawtry refused to play cards with him. He later passed out. The two men remained friends.

D-Day and European Campaign

Macleod attended Staff College, Camberley, in 1943. He graduated early in February 1944. This experience helped him find a purpose in life.

As a major, he landed in France on Gold Beach on D-Day, 6 June 1944. He was part of the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division. This division was very experienced. Their job was to capture Arromanches, where an artificial harbor would be built. Macleod spent much of D-Day checking on progress across the beachhead. He later said he had "a patchwork of memories" from that day. He remembered that his batman had filled his ammunition pouch with boiled sweets instead of bullets. British planners expected many casualties on D-Day. Macleod thought he would be killed. But when he survived, he decided he would live through the war.

By that autumn, he was telling people he planned to enter politics and become Prime Minister. He served in France and the Low Countries until November 1944. He ended the war as a major.

Post-War and First Election

Macleod ran for Parliament in the 1945 United Kingdom general election in the Western Isles. He came last in the vote. His father, who was a Liberal, supported him.

After the war, in May 1945, Macleod's division was sent to Norway. He was in charge of setting prices for wine and spirits there. In December 1945, he successfully defended a colonel in a military court. He left the army in January 1946.

Starting a Political Career

In 1946, Macleod joined the Conservative Parliamentary Secretariat. He wrote reports for Conservative MPs on topics like Scotland, employment, and health.

He was chosen as the Conservative candidate for Enfield in 1946. He faced a tough selection process. He was strongly supported by the local Young Conservatives. One of them was 15-year-old Norman Tebbit.

In 1948, the election boundaries changed. Macleod was chosen for the new, more winnable seat of Enfield West. He won this seat in February 1950 and held it easily throughout his career.

Macleod worked for the Conservative Research Department. He helped write the social services part of the Conservative policy paper The Right Road for Britain (1949). He was seen as a promising young politician, along with Enoch Powell, Angus Maude, and Reginald Maudling. They were all elected to Parliament in 1950. They became part of the "One Nation" group, which believed in a fairer society. Macleod and Angus Maude wrote a pamphlet called One Nation in 1950.

Political Career Highlights

Minister of Health

In October 1951, Winston Churchill became Prime Minister again. Macleod was not given a government job at first. But he became chairman of the backbench Health and Social Services Committee.

He gave a brilliant speech in Parliament on 27 March 1952. He spoke after Aneurin Bevan, a former Health Minister. Macleod strongly criticized Bevan's speech. Churchill, who was about to leave, stayed to listen. He asked who the promising young MP was. On 7 May, Macleod was appointed Minister of Health. This was not a Cabinet position at the time.

In 1952, Macleod announced that smoking was linked to lung cancer. He did this at a press conference while chain-smoking himself. Macleod managed the NHS well and protected its budget.

Minister of Labour

In December 1955, Prime Minister Anthony Eden promoted Macleod to the Cabinet. He became the Minister of Labour and National Service. Eden saw Macleod as a possible future Prime Minister. He thought this job would give him good experience dealing with trade unions.

Suez Crisis

Macleod was not directly involved in the secret plans for the Suez Crisis in 1956. He was unhappy with how things turned out but did not resign. He never publicly spoke against the Suez actions. He was part of Cabinet decisions that led to the crisis. For example, he agreed that Nasser's nationalization of the Suez Canal should be opposed, even with force if needed.

Some Cabinet members, including Macleod, wanted to delay military action. They wanted to try all other options first. On 25 October, Eden told the Cabinet about secret talks with Israel. On 30 October, Macleod and others were upset that ministers had not been fully informed. At one point, when Eden said they were "at war," Macleod famously snapped, "I was not aware that we were at war, Prime Minister!"

1958 Bus Strike

When Eden resigned in January 1957, Harold Macmillan became Prime Minister. Macleod, like most of his colleagues, supported Macmillan.

Macleod wanted to be a reforming Minister of Labour. He tried to create a Workers' Charter. He also wanted to be tougher on strikes than his predecessor. The unions were becoming more active under Frank Cousins, the head of the Transport and General Workers' Union.

Macleod's time as Minister of Labour included the 1958 London bus strike. Macmillan and the Cabinet decided to settle a separate railway strike. But on the bus strike, Macleod was told to fight Frank Cousins. The strike ended after seven weeks. Macleod gained a reputation as a tough figure.

Colonial Secretary

Macleod became Secretary of State for the Colonies in October 1959. He had never visited any of Britain's colonies before. He believed that the British Empire would soon end. He said he wanted to be the last Colonial Secretary. He oversaw the independence of many countries, including Nigeria, British Somaliland, Tanganyika, Sierra Leone, Kuwait, and British Cameroon. He toured Sub-Saharan Africa in 1960.

He often disagreed with Duncan Sandys, the Commonwealth Secretary, who was more conservative. Macmillan sometimes found Macleod too fast in his actions.

The state of emergency in Kenya ended in January 1960. The Lancaster House Conference agreed to a constitution for Kenya. This led to eventual black majority rule. Jomo Kenyatta was freed in August 1961. Kenya became fully independent in December 1963.

Macleod also attended the Ugandan Constitutional Conference in 1961. This conference created the first Ugandan Constitution. It took effect in October 1962.

In Nyasaland (now Malawi), Macleod pushed for the release of Hastings Banda. He even threatened to resign to get his way. Banda was released in April 1960. He was invited to London for talks about independence. Nyasaland became independent in 1963.

Macleod's policy for Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) was very complex. He wanted a Legislative Council with an African majority. This was strongly opposed by Roy Welensky, the Prime Minister of the Central African Federation. After much debate, a new constitution was agreed. This constitution helped to weaken the Central African Federation.

Macleod was keen to see colonies become independent peacefully. He helped achieve a deal with Julius Nyerere, the Prime Minister of self-governing Tanganyika. Tanganyika became fully independent in December 1961.

Historians have praised Macleod's work as Colonial Secretary. However, during his time, he ordered the destruction of some colonial papers. These documents detailed criminal acts from the 1940s and 1950s. This was done to avoid embarrassment for Britain and to protect people who had helped the British. Many documents were about the harsh actions during the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya.

Leader of the House and Party Chairman (1961–63)

In October 1961, Macmillan moved Macleod to new roles. He became Leader of the House of Commons and Chairman of the Conservative Party. He was also given the job of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster.

Macleod's time as Party Chairman saw poor election results for the Conservatives. This was partly due to tight economic policies. He told Macmillan that a big government reshuffle was needed in 1962. He suggested removing Selwyn Lloyd from the Exchequer. Macmillan then sacked many Cabinet members in what was called the "Night of the Long Knives".

Conservative Leadership Contest (1963)

Harold Macmillan resigned as Prime Minister in October 1963. Macleod was not a likely candidate to replace him. This was due to his difficult time as Party Chairman and his work as Colonial Secretary.

Macleod believed that Alec Douglas-Home (who later became Sir Alec) had not been honest about wanting to be leader. Macleod did not take Home's candidacy seriously at first. He didn't realize how much Macmillan was supporting Home. Macleod gave a great speech at the party conference. But Home's support grew.

When Home was chosen as the new leader, Macleod and Enoch Powell were very angry. They felt the choice was unfair. They tried to convince Rab Butler, Macmillan's deputy, not to serve in Home's government. They hoped this would stop Home from forming a government. Macleod and Powell eventually refused to serve under Home.

Some people believed Macleod's actions were tactical. They thought he might have hoped for a deadlock that would make him Prime Minister. But others, including his wife, disagreed.

Editor of The Spectator

Ian Gilmour appointed Macleod as editor of The Spectator magazine. He wrote a weekly column using the name "Quoodle." He also wrote articles complaining about things he disliked, such as Harold Wilson or the BBC.

On 17 January 1964, Macleod published an article about the 1963 leadership contest. He claimed it was a conspiracy by an "Etonian magic circle." This article caused a lot of controversy. Some colleagues avoided him in Parliament. The affair damaged his chances of ever becoming leader.

Macleod also became a director at Lombards Bank. This gave him a car and driver. He needed this because his spinal condition made it hard for him to drive.

Shadow Chancellor

Macleod returned to the shadow cabinet after the 1964 United Kingdom general election. He became the Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer. He focused on tax reform. He planned to abolish the Selective Employment Tax and cut income tax. He believed economic growth would make up for lost revenue.

In 1965, Macleod is credited with inventing the word "stagflation." He used it to describe a situation where there was both high inflation (rising prices) and high unemployment.

Macleod opposed the death penalty. He had good relationships with some Labour politicians, like James Callaghan. However, he often clashed with Callaghan in Parliament. He did not get along with Roy Jenkins, who later became Chancellor.

As Shadow Chancellor, Macleod helped found the homeless charity Crisis in 1967. In 1968, he voted against the Labour Government's Commonwealth Immigration Bill. He believed it broke promises made to Kenyan Asians. He also fell out with his former friend Enoch Powell over Powell's controversial "Rivers of Blood speech" in 1968. Macleod was horrified by the racism he saw in some public reactions to Powell's speech.

In the late 1960s, Macleod often attacked Prime Minister Harold Wilson. He called Wilson "an illusionist without ideals."

Chancellor of the Exchequer and Death

On 20 June 1970, two days after the Conservative Party's unexpected election win, Macleod was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer. This is one of the most important jobs in government.

Despite being in pain, he gave his only major speech on the economy as Chancellor on 7 July 1970. He spoke about high inflation and high unemployment. Later that day, he was rushed to hospital. He was discharged 11 days later. But on 20 July, while at 11 Downing Street, he suffered a heart attack and died.

It is believed that his wartime injury, smoking, and overwork contributed to his early death. His doctor said there was no evidence he had cancer.

Macleod left behind a detailed plan for tax reform. Much of it was later put into action. He also had plans to control public spending. One proposal was to stop providing free school milk in primary schools. The new Education Secretary, Margaret Thatcher, later made a compromise on this.

His death was a big loss for the Heath government. His successor, Anthony Barber, was less experienced. This allowed Heath to have more control over economic policy.

Oratory and Personality

Many politicians who came after Macleod remembered him as a very effective speaker. His bald head and sharp gaze made him stand out. He was one of the most powerful public speakers of his time. He was also a great negotiator and paid close attention to details.

He was known for being impatient with people he thought were foolish. As he got older, his disability made him more short-tempered.

His political opponent, Roy Jenkins, said Macleod had "a darting crossword-puzzle mind fortified by a phenomenal memory." Jenkins also said Macleod was "not convinced that he was a particularly nice man, but he had insight and insolence."

Macleod believed his political views were a mix of his Liberal father and Conservative mother. He often called himself a "Tory." He believed in equality of opportunity. He said his ideal was "to see that men had an equal chance to make themselves unequal."

He is credited with inventing the term "the nanny state."

Family Life

Macleod met Evelyn Hester Mason (born 1915, died 1999) in September 1939. She interviewed him for a job as an ambulance driver. Her first husband died in the war. Iain and Evelyn married on 25 January 1941. They had a son, Torquil, and a daughter, Diana.

In June 1952, Evelyn Macleod became very ill with meningitis and polio. She later learned to walk again with sticks. She worked hard to support her husband's career. After his death, she became a peer in 1971. She took her seat in the House of Lords as Baroness Macleod of Borve. Macleod's daughter, Diana Heimann, later became a political candidate.

Iain Macleod is buried in the churchyard of Gargrave Church in North Yorkshire. His mother had died seven weeks before him.

|

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |