Jomo Kenyatta facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Right Honourable

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta

CGH

|

|

|---|---|

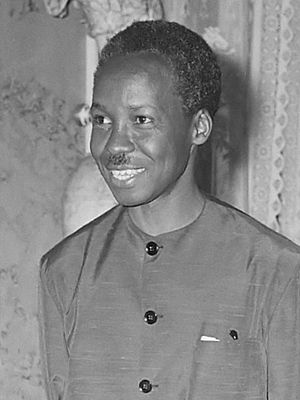

President Kenyatta in 1966

|

|

| 1st President of Kenya | |

| In office 12 December 1964 – 22 August 1978 |

|

| Vice President | Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Joseph Murumbi Daniel arap Moi |

| Preceded by | Elizabeth II as Queen of Kenya |

| Succeeded by | Daniel arap Moi |

| 1st Prime Minister of Kenya | |

| In office 1 June 1963 – 12 December 1964 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Succeeded by | Raila Odinga (2008) |

| Chairman of the Kenya African National Union (KANU) | |

| In office 1961–1978 |

|

| Preceded by | James Gichuru |

| Succeeded by | Daniel arap Moi |

| Member of Parliament for the Gatundu Constituency | |

| In office 1963–1978 |

|

| Preceded by | established |

| Succeeded by | Ngengi Wa Muigai |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Kamau wa Muigai

c. 1897 Ngenda, British East Africa |

| Died | 22 August 1978 (aged 80–81) Mombasa, Coast Province, Kenya |

| Resting place | Parliament Buildings, Nairobi, Kenya |

| Nationality | Kenyan |

| Political party | KANU |

| Spouses | Grace Wahu (m. 1919) Edna Clarke (1942–1946) Grace Wanjiku (d. 1950) Ngina Kenyatta

(m. 1951) |

| Children | 8 (including Margaret, Uhuru, Nyokabi and Muhoho) |

| Alma mater | University College London, London School of Economics |

| Notable work(s) | Facing Mount Kenya |

| Signature | |

Jomo Kenyatta (around 1897 – 22 August 1978) was a Kenyan leader who fought against colonialism. He served as Kenya's Prime Minister from 1963 to 1964. Then, he became Kenya's first President from 1964 until he passed away in 1978.

Kenyatta played a huge part in changing Kenya from a British colony into an independent country. He was a strong African nationalist and led the Kenya African National Union (KANU) party from 1961 until his death.

He was born to Kikuyu farmers in Kiambu, British East Africa. He went to a mission school and worked different jobs. Later, he became involved in politics through the Kikuyu Central Association. In the 1930s, he studied in Moscow and London. He wrote a book about Kikuyu life called Facing Mount Kenya in 1938.

After returning to Kenya in 1946, he became a school principal. In 1947, he was chosen to lead the Kenya African Union. He worked hard for Kenya's independence from British rule. He gained a lot of support from local people but faced opposition from white settlers. In 1952, he was arrested and accused of being involved in the Mau Mau Uprising. He said he was innocent, and many historians agree. He was imprisoned until 1959 and then sent away to Lodwar until 1961.

After his release, Kenyatta became the leader of KANU. He led the party to win the 1963 election. As Prime Minister, he guided Kenya to become an independent republic. He became president in 1964. He wanted Kenya to be a one-party state. He made the central government stronger and limited political opposition.

Kenyatta worked to bring together Kenya's different ethnic groups and the European minority. His government focused on capitalist economic policies. They also worked on "Africanisation" to give more control of the economy to Kenyans. Education and healthcare improved under his leadership. Kenya joined the Organisation of African Unity and the Commonwealth of Nations. He supported Western countries during the Cold War. Kenyatta died while still in office, and Daniel arap Moi took over. His son, Uhuru, later also became president of Kenya.

Kenyatta was a complex figure. During his time as president, he was called Mzee, meaning "grand old man," and seen as the Father of the Nation. He was praised for bringing people together. However, some people criticized his rule as being too strict. They also said he favored his own ethnic group and that there was a lot of corruption in his government.

Contents

Jomo Kenyatta's Early Life

Growing Up in Kenya

Jomo Kenyatta was born Kamau in the village of Ngenda. He was a member of the Kikuyu people. We don't know his exact birth date because records were not kept then. Some historians think he was born around 1897 or 1898. His father was Muigai, and his mother was Wambui. They lived on a farm near River Thiririka, where they grew crops and raised animals.

Kenyatta grew up following traditional Kikuyu customs. He learned how to herd the family's sheep and goats. When he was about ten, his earlobes were pierced, which was a sign of growing up. After his father died, his mother married his uncle, Ngengi. Kenyatta then took the name Kamau wa Ngengi, meaning "Kamau, son of Ngengi."

School Days and New Name

In November 1909, Kenyatta left home to go to school at the Church of Scotland Mission (CSM) in Thogoto. The missionaries wanted to teach Christianity to the local people. Kenyatta lived at the school and learned to read and write in English. He also helped with chores around the mission.

His school progress was not outstanding. In 1912, he became a carpenter's apprentice. In 1914, he was baptized as Johnstone Kamau. He chose the name Johnstone because he liked the sound of it. After his apprenticeship, he wanted to learn to be a stonemason, but the mission said no.

Working in Nairobi

Kenyatta moved to Thika and worked for an engineering company. He had to travel to Nairobi to get the company's wages. He later got sick and recovered at a friend's house. During World War I, many Kikuyu joined the British Army, but Kenyatta did not. He moved to live among the Maasai, who also refused to fight for the British. He adopted some Maasai customs and wore a beaded belt called kinyata. This is how he started calling himself "Kenyatta."

In 1917, he worked in Narok transporting livestock. Then he moved to Nairobi to work in a store. He also took evening classes at a church school. In 1919, he married Grace Wahu. Their son, Peter Muigui, was born in 1920. In 1922, Kenyatta started working for Nairobi's city council as a clerk. He earned a good salary, which gave him financial freedom. He lived in the Kilimani area of Nairobi and built another home in Dagoretti.

Becoming a Political Voice

Joining the Kikuyu Central Association

After World War I, many people in Kenya were unhappy with British rule. They disliked carrying identity cards and paying taxes without having a say in government. Kenyatta became interested in politics through his friend James Beauttah, who was a leader in the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA).

In 1925 or 1926, Beauttah suggested Kenyatta go to London to represent the KCA. Kenyatta agreed and became the group's secretary. He traveled around Kikuyuland and nearby areas to help set up new KCA branches. In 1928, he spoke to government groups about land issues. He also started using the name "Kenyatta" more often.

In May 1928, the KCA started a Kikuyu-language magazine called Muĩgwithania (meaning "The Reconciler"). Kenyatta was listed as the editor. The magazine aimed to unite the Kikuyu people and raise money for the KCA. In the magazine, Kenyatta spoke carefully, even praising the British Empire at times.

Journey to Europe

First Trip to London

In February 1929, Kenyatta sailed to Britain. The British government in Kenya tried to stop him from meeting with officials in London. He stayed at the West African Students' Union and met with people who opposed British rule. He also met with Edward Grigg, the Governor of Kenya, to discuss land issues.

Kenyatta also met with some communists and traveled to Moscow in the summer of 1929. He wrote articles for communist newspapers, criticizing British imperialism more strongly than before. These links worried some of his supporters. After 18 months, he ran out of money and returned to Kenya in September 1930. His time in Europe made him more respected among the Kikuyu.

Studying in Europe Again

In May 1931, Kenyatta returned to Britain to represent the KCA. He would stay in Europe for 15 years. He attended summer schools and conferences. In November, he met Mohandas Gandhi, a leader for India's independence. He also studied at Woodbrooke Quaker College in Birmingham.

Kenyatta became friends with George Padmore, an Afro-Caribbean Marxist. In late 1932, they went to Moscow, where Kenyatta studied at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East. He learned about Marxist-Leninist ideas. Many Africans went to this school because it offered free education and treated them with respect.

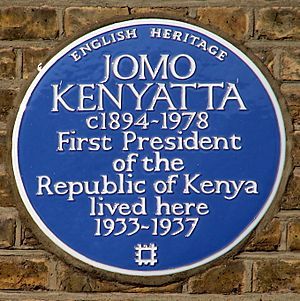

When the Nazis rose to power in Germany, the Soviet Union changed its focus. Padmore and Kenyatta left the Soviet Union, and Kenyatta returned to London in August 1933. British intelligence, MI5, watched him closely, thinking he might be a Marxist-Leninist.

Kenyatta continued to write articles, calling for Kenya to rule itself completely. This was a more radical idea than what other Kenyan politicians were saying at the time.

University and Facing Mount Kenya

Between 1935 and 1937, Kenyatta worked at University College London (UCL), helping with Kikuyu language recordings. He also studied social anthropology at the London School of Economics (LSE) under Bronisław Malinowski. Kenyatta wanted a degree to show he was as smart as white Europeans. He and Malinowski became good friends.

Kenyatta lived in London and became friends with other Africans. He appeared as an extra in a film called Sanders of the River. In 1935, when Italy invaded Ethiopia, Kenyatta became involved in groups supporting Ethiopia. He became a vice-chair of the International African Service Bureau (IASB). He gave talks across Britain, criticizing British colonial rule.

In 1938, Kenyatta published his book, Facing Mount Kenya. It was based on his studies of Kikuyu society. The book used anthropology to argue against colonialism. It showed Kikuyu society as organized and good, challenging the European idea that Africans were primitive. The book was published under the name "Jomo Kenyatta" for the first time.

During World War II

When World War II started in 1939, Kenyatta moved to Storrington, Sussex. He rented a flat and grew vegetables. He worked on a farm, which helped him avoid joining the military. In May 1942, he married an English woman named Edna Grace Clarke. Their son, Peter Magana, was born in August 1943.

Kenyatta was mostly quiet politically during the war. He wrote an essay calling for Kenya's political independence. He also helped plan the fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester in October 1945. At the conference, he supported the idea that Africans might need to use force to gain freedom if peaceful ways failed.

Return to Kenya and Fight for Independence

Leading the Kenya African Union

Kenyatta returned to Kenya in September 1946. He did not bring Edna and their son because of Kenya's strict racial laws. In Kenya, he was greeted by his first wife, Grace Wahu. He built a home in Gatundu and started farming. He also became the principal of the Koinange Independent Teachers' College.

In June 1947, Kenyatta was elected president of the Kenya African Union (KAU). KAU was the main political group for Africans in the colony. Kenyatta became very popular, and the Kikuyu press called him the "Saviour" and "Hero of Our Race." He worked to get support from other ethnic groups in Kenya. He made sure KAU meetings were in Swahili, which most Kenyans understood.

He also reached out to India's Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, for support. Relations with white settlers were difficult. They saw Kenyatta as their main enemy. White settlers wanted more control for themselves and closer ties with white-minority governments in other parts of Africa.

By 1952, Kenyatta was seen as a national leader. He publicly spoke against violence and illegal activities, including the Mau Mau Uprising. He urged people to work hard and get independence peacefully. Even though he spoke against the Mau Mau, some of its members saw him as a hero. They used his name in their oaths of loyalty.

Arrest and Imprisonment

In October 1952, Kenyatta was arrested and sent to Lokitaung, a very remote place in Kenya. The British authorities believed arresting him would stop unrest. They wanted him imprisoned, even though they had little evidence against him. He and five other KAU leaders, known as the "Kapenguria Six," were accused of leading the Mau Mau. Many historians now believe Kenyatta was a "scapegoat" and that the authorities knew he wasn't directly involved.

The trial took place in Kapenguria, a remote area. The defense team included lawyers from different countries. The judge, Ransley Thacker, was chosen by the government and was known to be sympathetic to their side. The main witness for the prosecution later admitted he had lied.

In April 1953, Judge Thacker found Kenyatta and the others guilty. They were sentenced to seven years of hard labor. Kenyatta said they did not accept the verdict, claiming the government used them to shut down KAU. The government then banned KAU and closed many independent schools, including Kenyatta's. They also took his land and destroyed his house in Gatundu.

Kenyatta and the others appealed their case many times, but their convictions were upheld. He remained imprisoned at Lokitaung. Because of his age, he was made the cook for the other inmates. His health suffered in prison.

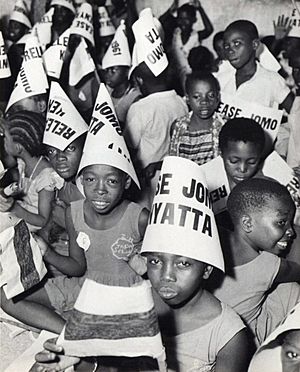

Calls for Release

Kenyatta's imprisonment made him a symbol for many Kenyans fighting for freedom. People like Jaramogi Oginga Odinga started calling for his release. The British writer Montagu Slater wrote a book about his trial, bringing more attention to the case. In 1958, the main witness against Kenyatta admitted he had lied, which was widely reported. By the late 1950s, Kenyatta was a symbol of African nationalism across the continent.

In April 1959, Kenyatta was released from Lokitaung but was forced to live in Lodwar, a remote area. His wife Ngina joined him there, and they had more children. The Governor of Kenya, Patrick Muir Renison, said Kenyatta was dangerous and should not be fully released.

However, many people around the world called for his freedom, including the Chinese government, India's Nehru, and leaders from other African countries like Julius Nyerere of Tanganyika and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. It became clear that Kenya would soon be independent. In January 1960, the British government began talks about Kenya's future.

The anti-colonial movement split into two parties: KANU (Kenya African National Union) and KADU (Kenya African Democratic Union). KANU nominated Kenyatta as its president, but the government refused. KANU then said it would not join any government until Kenyatta was freed.

Preparing for Independence

Governor Renison decided to release Kenyatta before independence. He thought people would be less likely to vote for him if they saw him first. In April 1961, Kenyatta was flown to Maralal. He maintained his innocence and said he held no grudges. He stated he was an "African Nationalist" and never supported violence.

In August, he moved to Gatundu, where a crowd of 10,000 people greeted him. The colonial government had built him a new house. Now free, he traveled to cities like Nairobi. In October 1961, Kenyatta officially joined KANU and became its president.

Kenyatta also traveled to other African countries. He faced a border dispute with Somalia over the Northern Frontier District. Kenyatta insisted the land belonged to Kenya.

He worked to gain the trust of white settlers, who were important for Kenya's economy. He promised them they would be safe in an independent Kenya. He also made it clear that white civil servants would not be fired unless skilled Kenyans could replace them. Many white Kenyans began to support KANU.

In 1962, Kenyatta went to London for talks about Kenya's new constitution. KANU and KADU had different ideas. KADU wanted a federal system with strong regional governments, while KANU wanted a strong central government. Kenyatta agreed to some of KADU's demands, knowing he could change the constitution later. A temporary government was formed, and Kenyatta became Minister of State for Constitutional Affairs.

The British government replaced Governor Renison with Malcolm MacDonald, who became good friends with Kenyatta. MacDonald sped up plans for Kenya's independence. An election was set for May, with self-government in June and full independence in December.

Leading Kenya

Prime Minister of Kenya

In the May 1963 election, Kenyatta's KANU party won most of the seats. On 1 June 1963, Kenyatta became the prime minister of Kenya's self-governing government. Kenya was still a monarchy, with Queen Elizabeth II as its head of state.

Kenyatta's image became central to the new nation. Nairobi's Delamere Avenue was renamed Kenyatta Avenue, and a statue of him was put up. His face appeared on the new currency. In 1964, a collection of his speeches was published called Harambee!.

Kenya's first cabinet included people from different ethnic groups. In June 1963, Kenyatta met with leaders from Tanganyika and Uganda to discuss forming an East African Federation. They agreed to do this by the end of the year, but Kenyatta was privately hesitant, and the federation did not happen.

Kenyatta continued to build good relations with white farmers, assuring them they were welcome. However, he did not do the same for the Indian minority. He also encouraged former Mau Mau fighters to leave the forests and rejoin society.

On 12 December 1963, Kenya celebrated its independence. Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, handed over control to Kenyatta. Kenyatta called it "the greatest day in Kenya's history."

Disputes with Somalia over the Northern Frontier District continued. Kenyatta sent soldiers to the region to deal with Somali shifta guerrillas. In January 1964, parts of the Kenyan army rebelled, and Kenyatta asked the British Army to help stop it. He then increased pay for the army and police to prevent future unrest. To limit political opposition, KADU dissolved in November 1964, and its members joined KANU. This made Kenya a one-party state in practice.

President of Kenya

In December 1964, Kenya became a republic, and Kenyatta became its first executive president. This meant he was both the head of state and head of government. Over the next two years, his powers as president grew. He appointed Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, a Luo, as his vice president. However, most important government jobs were held by Kikuyu people, which led to some feeling that one elite group had replaced another.

Kenyatta's government focused on forgiving past conflicts. He kept some parts of the old colonial system, especially in law and order. White Kenyans remained in important positions in the government and courts. His government did not allow dual citizenship, expecting everyone to be fully loyal to Kenya. Schools and social clubs that were once only for Europeans were opened to Africans and Asians.

The government worked to create a united Kenyan culture. They promoted African cultures that had been seen as "primitive" by missionaries. They supported African writers, artists, and musicians. Street names from colonial times were changed, and symbols of colonialism were removed. The government encouraged Swahili as a national language, but English remained important in parliament and schools.

Economic Policies

Kenya's economy was shaped by colonial rule, relying heavily on farming and exporting raw materials. Under Kenyatta, the economy remained capitalist. The government encouraged foreign investment, and foreign companies saw Kenya as a good place to invest.

Kenyatta's government aimed to bring the economy under Kenyan control. They wanted to replace Asian-owned businesses with African-owned ones. Laws were passed to help black-owned businesses and give Kenyans more control over trade. Many Asians who had British citizenship were affected by these laws, and some moved to Britain.

Some people criticized Kenyatta's government for corruption. Kenyatta and his family were said to have gained a lot of land and wealth after 1963. They invested in hotels, mining, and other businesses. The Kenyan press did not report much on this at the time.

Land, Health, and Education

Land ownership was a big issue in Kenya. The British government gave Kenya money to buy land from white farmers and give it to Kenyans. Kenyatta's government encouraged private companies, often led by politicians, to buy and divide this land. This meant that land often went to people connected to the ruling party.

Many people moved from rural areas to cities, leading to unemployment and housing shortages in cities. Kenyatta's government tried to control trade unions to prevent economic disruption. They also worked to have more Africans in civil service jobs.

Education greatly expanded under Kenyatta. The government aimed for universal free primary education. They focused on secondary and higher education to train Kenyans for important jobs. The number of primary and secondary schools grew a lot. By the time Kenyatta died, Kenya had its first universities, the University of Nairobi and Kenyatta University.

Healthcare also improved. The government aimed for free, universal medical care. They increased the number of doctors and nurses. By Kenyatta's death, most Kenyans had much better healthcare than before independence. Life expectancy increased from 45 to 55 years. However, the population grew very quickly, putting a strain on services.

Foreign Relations

Kenyatta rarely traveled outside East Africa. Kenya did not get deeply involved in other countries' affairs. In 1967, Kenya signed a treaty for East African Co-operation. Kenyatta also helped mediate during the Congo Crisis.

Kenya officially followed a policy of "positive non-alignment" during the Cold War. But in reality, its foreign policy was pro-Western, especially pro-British. Kenya joined the British Commonwealth. Britain was a major trading partner and provided a lot of aid.

Kenyatta had good relations with the United States and Israel. He allowed Israeli jets to refuel in Kenya during the Entebbe raid. In turn, Israel warned him about a plot to assassinate him.

Kenyatta and his government were against communism. In 1965, he warned against "imperialism from the East." His government was often criticized by communists. Relations with China and the Soviet Union were sometimes strained.

Political Dissent

Kenyatta wanted Kenya to be a one-party state, believing it would show national unity. He made the central government stronger, reducing the power of Kenya's provinces.

Divisions within KANU grew. In 1966, the power of Vice President Odinga was reduced. In 1966, Odinga stepped down and formed a new party, the Kenya Peoples Union (KPU). The KPU wanted more socialist policies and criticized Kenyatta's government for being too capitalist. The KPU became the official opposition party.

To weaken the KPU, the government changed the constitution. This meant KPU members had to run for re-election. The KPU faced difficulties campaigning, and KANU controlled the national media. Only a few KPU members were re-elected.

In July 1969, a popular Luo politician, Thomas Mboya, was killed. This caused tension between ethnic groups. In October 1969, Kenyatta visited Kisumu, a Luo area, and his bodyguards opened fire on a crowd, killing and wounding people. Kenyatta also introduced a Kikuyu tradition of oathing, where people swore loyalty to him. This was criticized and later stopped.

Kenyatta's government used strict laws to limit opposition. In 1966, a law allowed authorities to detain people without trial if they threatened state security. In October 1969, the KPU was banned, and Odinga was arrested. Kenya became a one-party state again. Many other political figures who criticized Kenyatta were detained or imprisoned. Some critics were killed in incidents that many believed were government assassinations.

Illness and Death

Kenyatta had health problems for many years, including strokes and heart issues. By the 1970s, his health was declining. A small group of Kikuyu politicians became his closest advisors. In March 1975, a politician named Josiah Mwangi Kariuki was murdered. This led to less public support for Kenyatta's government.

On 22 August 1978, Kenyatta died of a heart attack in Mombasa. The Kenyan government had planned for his death for years, even asking Britain for help with his state funeral. The funeral was held six days later at St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church. Charles, Prince of Wales, attended, showing the importance of Kenya to Britain. Many African leaders also attended. Kenyatta was buried in a mausoleum at the Parliament Buildings in Nairobi.

After Kenyatta's death, the transfer of power was smooth. Vice President Daniel arap Moi became acting president. Moi was later elected president. Moi emphasized his loyalty to Kenyatta but also criticized the corruption and land issues from Kenyatta's time. In 1982, Moi would make Kenya officially a one-party state.

Kenyatta's Ideas and Personality

Political Beliefs

Kenyatta was an African nationalist. He believed that European colonial rule in Africa had to end. He thought Africa's resources were used for Europe's benefit, not for Africans. For him, independence meant not just self-rule, but also an end to racial discrimination. He believed all people should be free to develop peacefully.

Historians have described Kenyatta as politically conservative and a pragmatist. He focused on practical solutions. He believed in the importance of authority and tradition. He also encouraged self-help and hard work. Kenyatta wanted an elite class to emerge in Kenya. He tried to balance traditional Kikuyu customs with modern Western ideas.

Views on Pan-Africanism and Socialism

While in Britain, Kenyatta worked with people who believed in Marxism and Pan-Africanism, the idea that African countries should unite. Some people see him as a Pan-Africanist. However, as Kenya's leader, he became more conservative.

Kenyatta had learned about Marxist ideas but did not use them to guide Kenya's economy. He disagreed with the Marxist idea that tribalism was bad. He believed in individual and land rights, which was different from socialist ideas of collective ownership. His government promoted capitalism as an African idea and saw communism as foreign.

Personality and Private Life

Kenyatta was a lively and outgoing person. He enjoyed being at the center of things. He liked to dress well, often wearing rings and a fez. He adopted the name "Kenyatta" from a beaded belt he wore. As president, he collected expensive cars.

He was good at hiding his true intentions, especially his past links with communists. He could appear different to different people. He was described as shrewd and subtle. He had a strong temper but was not physically cruel. Kenyatta did not have racist feelings towards white Europeans, as shown by his marriage to an English woman. He wanted a Kenya where all races could live peacefully. However, he generally disliked Indians, believing they exploited Africans.

Kenyatta had two children with his first wife, Grace Wahu: Peter Muigai Kenyatta (born 1920) and Margaret Kenyatta (born 1928). Margaret later became mayor of Nairobi and an ambassador. She was his closest confidante.

Kenyatta said he was a Christian but did not follow one specific church. He was interested in different religions. He found the attitudes of some European missionaries difficult, especially their view that African traditions were evil. In his book, he defended African customs like ancestor veneration.

Kenyatta's Legacy

In Kenya, Kenyatta became known as the "Father of the Nation" and was called Mzee. A strong cult of personality grew around him, linking Kenyan nationalism with his image. He was seen as a father figure by many in Kenya and across Africa.

After 1963, Kenyatta was admired on the world stage, especially by Western countries. He was seen as a wise leader. His anti-communist views made him popular in the West, and he received awards from different governments.

Historians say that Kenya made great progress in health and education under Kenyatta. Life expectancy increased, and more children went to school. His government also peacefully ended racial segregation in schools and public places.

While many white settlers initially feared Kenyatta, by 1964, many called him "Good Old Mzee." His message of reconciliation, "to forgive and forget," was seen as a major contribution to his country.

However, some younger Kenyans and left-wing critics saw Kenyatta as too conservative. They compared Kenya unfavorably to Tanzania, which pursued more socialist policies. Some critics said Kenyatta's government did not treat Mau Mau veterans well, leaving many poor. His government also made little progress in women's rights.

Some scholars argue that Kenyatta, like other African leaders, helped achieve independence but also set up authoritarian rule. They point to his role in creating a one-party state and limiting political freedom.

In 2013, Kenya's Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission said that Kenyatta used his power to gain large amounts of land for himself and his family. The Kenyatta family is still among Kenya's biggest landowners. In the 1990s, there was frustration among some ethnic groups who felt they had not gotten back land taken by European settlers. This led to violence in some areas.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Jomo Kenyatta para niños

In Spanish: Jomo Kenyatta para niños