Kwame Nkrumah facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kwame Nwai Nkrumah

|

|

|---|---|

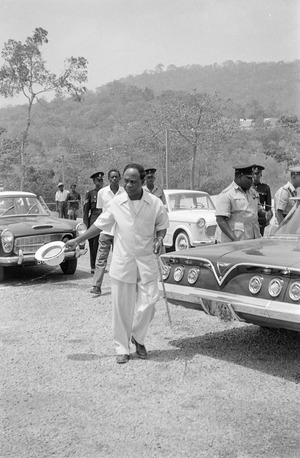

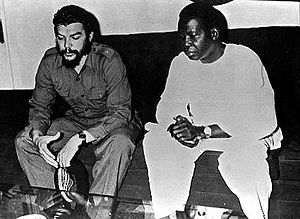

Nkrumah in 1961

|

|

| President of Ghana |

|

| In office 1 July 1960 – 24 February 1966 |

|

| Preceded by | Elizabeth II as Queen of Ghana |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Arthur Ankrah as Chairman of the NLC |

| 3rd Chairperson of the Organisation of African Unity | |

| In office 21 October 1965 – 24 February 1966 |

|

| Preceded by | Gamal Abdel Nasser |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Arthur Ankrah |

| 1st Prime Minister of Ghana | |

| In office 6 March 1957 – 1 July 1960 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governor-General | Charles Arden-Clarke The Lord Listowel |

| Preceded by | Himself as Prime Minister of the Gold Coast |

| Succeeded by | Himself as President |

| 1st Prime Minister of the Gold Coast | |

| In office 21 March 1952 – 6 March 1957 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governor-General | Charles Arden-Clarke |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Himself as Prime Minister of Ghana |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 21 September 1909 Nkroful, Gold Coast (now Ghana) |

| Died | 27 April 1972 (aged 62) Bucharest, Romania |

| Political party | United Gold Coast Convention (1947–1949) Convention People's Party (1949–1966) |

| Spouse |

Fathia Rizk

(m. 1957) |

| Children | Gamal Samia Francis Sekou |

| Education | Lincoln University (BA, (BTh)) University of Pennsylvania (MA, MS) London School of Economics University College London Gray's Inn |

| Awards | Lenin Peace Prize (1962) |

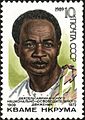

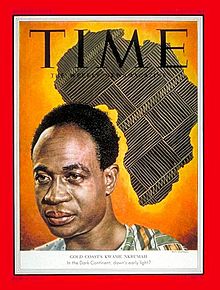

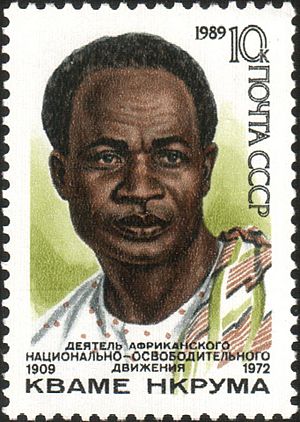

Dr. Francis Kwame Nkrumah (21 September 1909 – 27 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician and revolutionary. He became the first Prime Minister and President of Ghana. He led the Gold Coast to become independent from Britain in 1957. Nkrumah was a strong supporter of Pan-Africanism. This idea promotes the unity of all African people. He helped create the Organization of African Unity. In 1962, he won the Lenin Peace Prize from the Soviet Union.

Nkrumah spent twelve years studying and developing his political ideas abroad. He also worked with other Pan-Africanists. When he returned to the Gold Coast, he started his political career. He wanted his country to be independent. He formed the Convention People's Party, which quickly became popular. He became Prime Minister in 1952. Ghana gained independence in 1957, and he kept his position. In 1960, Ghanaians voted for a new constitution and elected Nkrumah as President.

His government focused on socialist and nationalist ideas. It funded big projects for industry and energy. He also built a strong national education system. Nkrumah promoted a culture that celebrated African unity. Ghana played a key role in African international relations during the time when many African countries became independent.

Nkrumah's rule in Ghana became more controlling. He limited political opposition and held elections that were not truly fair. In 1964, a change to the constitution made Ghana a one-party state. Nkrumah became president for life. In 1966, the National Liberation Council removed Nkrumah from power. After this, many state-owned businesses were sold to private companies. Nkrumah lived the rest of his life in Guinea. He was named an honorary co-president there.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Return to the Gold Coast

- Leading Ghana to Independence

- Ghanaian Independence

- Ghana's Leader (1957–1966)

- Overthrow from Power

- Exile, Death, and Legacy

- Personal Life

- Cultural Depictions

- Works by Kwame Nkrumah

- Festival

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Education

Growing Up in the Gold Coast

Kwame Nkrumah was born on 21 September 1909 in Nkroful, a small village in the Gold Coast. This area is now part of Ghana. His father worked as a goldsmith and did not live with the family. Kwame was raised by his mother and other relatives. He had a happy childhood, spending time in the village and by the sea.

According to local customs, he was named Kwame because he was born on a Saturday. Later, he changed his name to Kwame Nkrumah in 1945. His mother, Elizabeth Nyanibah, sent him to a Catholic elementary school. He was a very good student. A German priest, George Fischer, greatly influenced his early education.

Around 1925, he became a student-teacher at the school. He was also baptized as a Catholic. A school principal named Alec Garden Fraser noticed Nkrumah's talent. Fraser arranged for Nkrumah to train as a teacher at Achimota School in Accra. There, he learned about the ideas of Marcus Garvey and W. E. B. Du Bois. These thinkers believed in black self-rule. Nkrumah soon felt that African people needed to govern themselves for true harmony.

After getting his teaching certificate in 1930, Nkrumah taught in Elmina and then became a headmaster in Axim. In Axim, he started getting involved in politics. He also considered becoming a priest. He met Nnamdi Azikiwe, a journalist who later became Nigeria's president. Azikiwe's ideas increased Nkrumah's interest in black nationalism. Nkrumah decided to continue his education. Azikiwe suggested Lincoln University (Pennsylvania) in the United States. Nkrumah got money from relatives and traveled to the US in October 1935. On his way, he was upset to learn about Italy's invasion of Ethiopia.

Studies in the United States

Nkrumah spent ten important years in the United States. He arrived in New York in October 1935 and went to Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. He didn't have much money, so he worked jobs like washing dishes. He also visited black churches in Philadelphia and New York on Sundays.

He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics and sociology in 1939. Lincoln University then made him an assistant philosophy lecturer. He also started preaching in churches. In 1939, Nkrumah began studying at Lincoln's seminary and the University of Pennsylvania. He earned a Bachelor of Theology degree in 1942. The next year, he earned a Master of Arts in philosophy and a Master of Science in education from Penn.

During summers, Nkrumah spent time in Harlem, New York City. This was a lively center of black culture. He listened to street speakers and learned a lot from them. These discussions were a big part of his education.

Nkrumah was an active student leader. He organized African students in Pennsylvania. This group grew into the African Students Association of America and Canada, and he became its president. He pushed for a Pan-African approach, meaning all African colonies should work together for independence. He played a big role in a Pan-African conference in New York in 1944. This conference asked the United States to help Africa become developed and free after World War II.

Learning in London

Nkrumah moved to London in May 1945. He first enrolled at the London School of Economics to study anthropology. He later went to University College London to write a philosophy paper. He also started studying law at Gray's Inn, but he didn't finish.

He spent most of his time organizing political activities. He and George Padmore helped organize the Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester in October 1945. This meeting created a plan to replace colonialism with African socialism. They wanted a united Africa with different regions working together. They aimed for a new African culture that mixed old traditions with modern ideas. They hoped to achieve this peacefully. Important future leaders like Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya also attended.

Nkrumah became the secretary of the West African National Secretariat (WANS). This group worked for the independence of West African nations. Nkrumah also helped many West African sailors who were stranded in London after the war. He created the Coloured Workers Association to support them. British and US intelligence agencies watched Nkrumah because they worried about his links to Communism. Nkrumah and Padmore formed a group called The Circle. This group aimed to create a Union of African Socialist Republics. A document from The Circle was found when Nkrumah was arrested in 1948. British authorities used it against him.

Return to the Gold Coast

Joining the United Gold Coast Convention

In 1946, the Gold Coast constitution gave Africans more power in the government. This led to the creation of the first political party, the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), in August 1947. The UGCC wanted self-government quickly. They hired Nkrumah as their general secretary. Nkrumah was unsure at first because the UGCC was led by more traditional politicians. But he saw it as a great chance to get involved in politics. After British officials questioned him about his communist ties, Nkrumah sailed home in November 1947.

He arrived in the Gold Coast and started working at the UGCC headquarters in Saltpond in December 1947. Nkrumah quickly suggested plans for UGCC branches across the colony. He also proposed strikes to achieve political goals. This active approach caused disagreements within the party, led by J. B. Danquah. Nkrumah traveled around to raise money and open new UGCC branches.

Even though the Gold Coast was more politically advanced, there was a lot of unhappiness. Prices were high after the war, leading to a boycott of Arab-run stores in January 1948. Cocoa farmers were also angry because the government was destroying diseased cocoa trees. Many former soldiers couldn't find jobs and felt ignored by the government. Nkrumah and Danquah spoke at a meeting of ex-servicemen in Accra in February 1948. This meeting prepared for a march to the governor. On 28 February, during the march, British forces fired shots. This led to the 1948 Accra riots across the country.

The government believed the UGCC caused the unrest. They arrested six leaders, including Nkrumah and Danquah. These "Big Six" were held together in Kumasi. This increased the tension between Nkrumah and the others, who blamed him for the riots. They were freed in April 1948. Many students and teachers who protested for their release were suspended. Nkrumah used his own money to start the Ghana National College for them. This made UGCC members accuse him of acting without party permission. To keep him from causing more trouble outside the party, they made him honorary treasurer. Nkrumah's popularity grew even more. He started the Accra Evening News, which he owned with others. He also founded the Committee on Youth Organization (CYO) as a youth group for the UGCC. It soon broke away, calling for "Self-Government Now." The CYO brought together students, ex-soldiers, and market women. Nkrumah knew he would eventually leave the UGCC. He wanted the support of the people when that happened. His calls for "Free-Dom" attracted many young, unemployed people from villages to towns. People sang new liberation songs, welcoming Nkrumah to rallies across the Gold Coast.

Forming the Convention People's Party

By April 1949, many of Nkrumah's supporters wanted him to leave the UGCC and start his own party. On 12 June 1949, he announced the creation of the Convention People's Party (CPP). He chose "convention" to show he wanted to include everyone. There were attempts to fix the split with the UGCC. At one meeting, it was agreed to make Nkrumah secretary again and close the CPP. But Nkrumah's supporters convinced him to refuse and stay their leader.

The CPP chose the red cockerel as its symbol. This was a familiar sign for local groups. It represented leadership, alertness, and strength. Party symbols and colors (red, white, and green) appeared on clothes, flags, and vehicles. CPP workers drove red-white-and-green vans across the country. They played music and gathered support for the party and Nkrumah. These efforts were very successful. Earlier political groups had only focused on educated city people.

The British government formed a group of educated Africans to write a new constitution. This group included all the Big Six except Nkrumah. Nkrumah saw that their ideas would not lead to full independence. He began to plan a "Positive Action" campaign. Nkrumah demanded a special assembly to write a constitution. When the governor, Charles Arden-Clarke, didn't agree, Nkrumah called for Positive Action. Unions started a general strike on 8 January 1950. The strike quickly turned violent. Nkrumah and other CPP leaders were arrested on 22 January. The Evening News newspaper was banned. Nkrumah was sentenced to three years in prison. He was held with other prisoners in Accra's Fort James.

Nkrumah's assistant, Komla Agbeli Gbedemah, led the CPP while Nkrumah was in prison. Nkrumah still influenced events by sending notes written on toilet paper. The British prepared for an election under their new constitution. Nkrumah insisted that the CPP run for all seats. The situation became calmer after Nkrumah's arrest. The CPP and the British worked together to prepare voter lists. Nkrumah ran for an Accra seat from prison. Gbedemah set up a national campaign, using vans with loudspeakers. The UGCC failed to organize across the country. They couldn't take advantage of the fact that many opponents were in prison.

In the February 1951 election, the CPP won by a landslide. This was the first general election in colonial Africa where everyone could vote. The CPP won 34 out of 38 seats. Nkrumah was elected for his Accra area. The UGCC won three seats. Governor Arden-Clarke realized that the only choice was to free Nkrumah. Nkrumah was released from prison on 12 February. His supporters gave him a huge welcome. The next day, Arden-Clarke asked him to form a government.

Leading Ghana to Independence

Leader of Government and Prime Minister

When Nkrumah took office, he faced challenges. He had never been in government before. The Gold Coast was made of four different regions. Nkrumah wanted to unite them into one nation and gain full independence. He needed to convince the British that the CPP's plans were good and necessary. Nkrumah and Governor Arden-Clarke worked closely. The governor told government workers to fully support the new government. The three British members of the cabinet did not vote against the African majority.

Before the CPP took office, British officials had a ten-year development plan. Nkrumah approved it but wanted to finish it in five years. The colony had good finances from cocoa profits saved in London. Nkrumah could spend a lot of money. New main roads were built along the coast and inland. The train system was updated and expanded. Modern water and sewer systems were put in most towns. New housing projects also began. Construction started on a new harbor at Tema, near Accra. The existing port at Takoradi was also expanded. An urgent program began to build and expand schools, from primary to teacher training. From 1951 to 1956, the number of students in schools grew from 200,000 to 500,000. However, there weren't enough graduates for the growing government jobs. In 1953, Nkrumah said that while Africans would be preferred, the country would still need European civil servants for several years.

Nkrumah's title was Leader of Government Business. The cabinet was led by Arden-Clarke. Progress was fast. In 1952, the governor stepped back from the cabinet. Nkrumah became Prime Minister. The jobs that were for British officials now went to Africans. There were some accusations of corruption. Some officials were accused of favoring their families or tribes, following old African customs. After the 1948 riots, it was suggested that local governments should be elected, not controlled by chiefs. This idea became controversial when the CPP started to put it into action. The CPP's majority in the Legislative Assembly passed a law in late 1951. This law shifted power from chiefs to council leaders. There were some local riots when new taxes were put in place.

Nkrumah becoming Prime Minister didn't give him more power. He wanted changes to the constitution that would lead to independence. In 1952, he talked with the British Colonial Secretary, Oliver Lyttelton. Lyttelton said Britain would support more progress if chiefs and others agreed. Nkrumah then asked for opinions on reform from councils and political parties. He talked to many groups across the country, including opposition groups. In June 1953, a plan for a new constitution was published. This was seen as the last step before independence. Both the assembly and the British accepted the plan. It came into effect in April 1954. The new document created an assembly of 104 members, all elected directly. It also had an all-African cabinet in charge of governing the colony. In the election on 15 June 1954, the CPP won 71 seats. The regional Northern People's Party became the main opposition.

Several opposition groups formed the National Liberation Movement (NLM). They wanted a federal government for an independent Gold Coast, not a single, central government. They also wanted an upper house of parliament where chiefs could balance the CPP's power. They had strong support in the Northern Territory and among chiefs in Ashanti. They asked the British queen, Elizabeth II, to investigate the best government for the Gold Coast. Her government refused, saying the people of the Gold Coast should decide. Amidst political violence, the two sides tried to agree. But the NLM refused to join any committee with a CPP majority. The chiefs were also angry about a new law. This law allowed minor chiefs to ask the government in Accra for help, bypassing traditional chief authority. The British wanted to settle how an independent Gold Coast would be governed. In June 1956, the Colonial Secretary, Alan Lennox-Boyd, announced another election. If a "reasonable majority" supported the CPP's plan, Britain would set an independence date. The results of the July 1956 election were almost the same as four years before. On 3 August, the assembly voted for independence. They chose the name Nkrumah suggested in April, Ghana. In September, the British announced independence day would be 6 March 1957.

On 21 February 1957, the British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, announced that Ghana would be a full member of the Commonwealth of Nations from 6 March. The opposition was not happy and wanted power to be given to the regions. Discussions continued into 1957. Nkrumah insisted on a single, unified state. However, the nation was divided into five regions. Some power was given from Accra to these regions. Chiefs also had a role in their governments.

Ghanaian Independence

Ghana became independent on 6 March 1957. It was the first British colony in Africa to gain independence with majority rule. The celebrations in Accra attracted worldwide attention. Over 100 reporters and photographers covered the events. US President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent his vice president, Richard Nixon. The Soviet Union invited Nkrumah to visit Moscow. Ralph Bunche, an African American political scientist, was there for the United Nations. The Duchess of Kent represented Queen Elizabeth. Offers of help came from all over the world. Ghana seemed rich, with high cocoa prices and new resources.

As March 5th turned into March 6th, Nkrumah stood before thousands of supporters. He declared, "Ghana will be free forever." On Independence Day, he spoke at the first session of the Ghana Parliament. He told citizens, "we have a duty to prove to the world that Africans can conduct their own affairs with efficiency and tolerance and through the exercise of democracy. We must set an example to all Africa."

Nkrumah was called the Osagyefo. This means "redeemer" in the Akan language. The independence ceremony included the Duchess of Kent and Governor General Charles Arden-Clarke. With over 600 reporters, Ghana's independence became a major international news story.

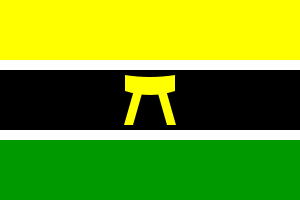

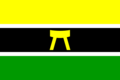

Theodosia Okoh designed the flag of Ghana. It uses green, yellow, and red, like Ethiopia's flag. It has a black star instead of a lion. Red stands for bloodshed, green for beauty and agriculture, yellow for mineral wealth. The Black Star represents African freedom. Amon Kotei designed the new coat of arms. It includes eagles, a lion, a St. George's Cross, and a Black Star. Philip Gbeho composed the new national anthem, "God Bless Our Homeland Ghana".

To celebrate the new nation, Nkrumah opened Black Star Square in Osu, Accra. This square was used for national events and large patriotic rallies.

Under Nkrumah, Ghana adopted some social democratic policies. He created a welfare system and started community programs. He also established schools.

Ghana's Leader (1957–1966)

Political Changes and Presidential Election

Nkrumah faced challenges soon after independence. Troops were sent to Togo-land to stop unrest after a vote about joining Ghana. A serious bus strike in Accra happened because the Ga people felt other tribes were getting better government jobs. This led to riots in August. Nkrumah responded by passing the Avoidance of Discrimination Act in December 1957. This law banned political parties based on region or tribe. He also removed many local chiefs in Ashanti who didn't support his party. These actions worried opposition parties. They formed the United Party led by Kofi Abrefa Busia.

In 1958, an opposition member of parliament was arrested. He was accused of trying to get weapons abroad for a plot against the Ghana Army. Nkrumah believed there was a plan to assassinate him. He responded by having parliament pass the Preventive Detention Act. This law allowed people to be jailed for up to five years without charges or a trial. Only Nkrumah could release them early. This law greatly damaged Nkrumah's reputation. Nkrumah wanted to bypass the British-trained judges. He felt they were against his plans.

Another issue was the regional assemblies. These were set up temporarily for constitutional talks. The opposition, strong in Ashanti and the north, wanted the assemblies to have significant powers. The CPP wanted them to be mostly advisory. In 1959, Nkrumah used his majority in parliament to pass the Constitutional Amendment Act. This law ended the assemblies. It also allowed parliament to change the constitution with a simple majority vote.

Queen Elizabeth II remained Ghana's Queen from 1957 to 1960. William Hare, 5th Earl of Listowel was the Governor-General, and Nkrumah was Prime Minister. On 6 March 1960, Nkrumah announced plans for a new constitution. This constitution would make Ghana a republic with a president who had strong powers. The plan also included giving up Ghanaian independence to a Union of African States. On 19, 23, and 27 April 1960, a presidential election and a vote on the constitution were held. The constitution was approved. Nkrumah was elected president over J. B. Danquah, the opposition candidate. Nkrumah won with 1,016,076 votes to Danquah's 124,623. Ghana remained part of the British-led Commonwealth of Nations.

Controlling Tribalism

Nkrumah also wanted to reduce "tribalism". He felt that loyalty to tribes was stronger than loyalty to the nation. He wrote that Ghana was fighting "a war against poverty and disease, against ignorance, against tribalism and disunity." To achieve this, in 1958, his government passed a law. This law banned groups that used racial or religious ideas to harm others. It also banned groups that tried to elect people based on their race or religion. Nkrumah tried to spread national flags everywhere. He also banned tribal flags, though this ban was often ignored.

Kofi Abrefa Busia of the United Party (Ghana) became a leading opposition figure. He criticized the ban on tribal politics as unfair. Soon after, he left the country. Nkrumah was also a very showy leader. The New York Times wrote in 1972 that Nkrumah was a "flamboyant spellbinder." He created a "cult of personality" and loved the title 'Osagyefo' (Redeemer). He met with world leaders as the first person to lead an African colony to independence after World War II.

During his time as Prime Minister and President, Nkrumah reduced the power of local chiefs. These chiefs had kept their authority by working with the British. The CPP had a difficult relationship with the chiefs. This relationship became worse as the CPP encouraged opposition to chiefs. They criticized the chief system as undemocratic. Laws passed in 1958 and 1959 gave the government more power to remove chiefs directly. These laws also gave the government control over land owned by chiefs and its income. These policies made the chiefs unhappy. They started to support the idea of overthrowing Nkrumah and his party.

More Power for the Convention People's Party

In 1962, three younger members of the CPP were accused of plotting to blow up Nkrumah's car. The only evidence was that they were in cars behind Nkrumah's. When they were found not guilty, Nkrumah fired the chief judge. Then, he had the CPP-controlled parliament pass a law allowing a new trial. At this second trial, all three men were found guilty and sentenced to death. Their sentences were later changed to life in prison. Soon after, the constitution was changed. This gave the president the power to remove judges at any time.

In 1964, Nkrumah proposed a constitutional change. This change would make the CPP the only legal party. It would also make Nkrumah president for life of both the nation and the party. The change passed with 99.91 percent of the vote. This very high number made observers believe the vote was "obviously rigged." Ghana had already been a one-party state since independence. This change made Nkrumah's presidency a legal dictatorship in practice.

Government Services

Between 1952 and 1960, many Ghanaians took over jobs in the civil service. However, from 1960 to 1965, the number of foreign workers increased again. Many of these new workers came from the Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Italy.

Education for All

In 1951, the CPP created the Accelerated Development Plan for Education. This plan set up a six-year primary school course. The goal was for almost all children to attend. Children would learn math and get a "sound foundation for citizenship with permanent literacy in both English and the vernacular." Primary education became required in 1962. The plan also said that religious schools would no longer get government money. Some missionary schools would be taken over by the government.

In 1961, Nkrumah started building the Kwame Nkrumah Ideological Institute. This institute trained Ghanaian government workers. It also promoted Pan-Africanism. In 1964, all students entering college in Ghana had to attend a two-week "ideological orientation" at the institute. Nkrumah said that students should see the party's ideas as a religion. They should practice it faithfully.

In 1964, Nkrumah introduced the Seven Year Development Plan. This plan focused on rebuilding and developing the nation. It said education was key for development. It called for more technical secondary schools. Secondary education would also include "in-service training programs." Nkrumah told Parliament that employers should contribute more to training workers. This would be done through factory schools, training schemes, and paying for short courses. This training would get indirect help from tax credits.

In 1952, the Artisan Trading Scheme was set up with the British Colonial Office. It allowed a few experts in each field to travel to Britain for technical training. The Kumasi Technical Institute was founded in 1956. In September 1960, it added a Technical Teacher Training Centre. In 1961, the CPP passed the Apprentice Act. This law created a general Apprenticeship Board and committees for each industry.

Promoting Ghanaian Culture

Nkrumah strongly supported pan-Africanism. He saw it as a way to unite the entire African continent. His time in politics was called the "golden age of high pan-African ambitions." Many African countries were gaining independence. There was a strong feeling of rebirth and unity in the Pan-African movement. Nkrumah often wore traditional Ghanaian clothes, like a fugu made with Kente cloth. This showed his identity as a leader for the whole country. He opened the Ghana Museum in 1957. He also opened the Arts Council of Ghana in 1958. In 1961, the Research Library on African Affairs opened. The Ghana Film Corporation started in 1964. In 1962, Nkrumah opened the Institute of African Studies.

Laws passed in 1959 and 1960 created special positions for women in parliament. Some women were promoted to the CPP Central Committee. More women attended universities and became doctors and lawyers. They also traveled to Israel, the Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe for professional trips. Women even joined the army and air force. Most women still worked in farming and trade. Some received help from the Co-operative Movement.

Nkrumah's image was widely used on stamps and money, like monarchs. This led to accusations that he was creating a personality cult.

Media and Information

In 1957, Nkrumah created the well-funded Ghana News Agency. This agency produced local news and sent it abroad. Within ten years, it had many telegraph lines across Ghana. It also had offices in Lagos, Nairobi, London, and New York City.

Nkrumah gained control over newspapers. He started the Ghanaian Times in 1958. In 1962, he bought its competitor, the Daily Graphic. He believed that in a capitalist system, the press could not be truly factual. He felt the press should not be privately owned. Starting in 1960, he used his power to check all news before it was published.

The Gold Coast Broadcasting Service started in 1954. It was later renamed the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC). Many TV shows featured Nkrumah. He would comment on issues like the "insolence and laziness of boys and girls." Before May Day celebrations in 1963, Nkrumah announced on TV that Ghana's Young Pioneers would expand. He also introduced a National Pledge and a National Flag salute in schools. He created a National Training program to teach good values to Ghanaian youth. Nkrumah told Parliament in 1963 that Ghana's television would not be for cheap entertainment. Its main goal would be education in its purest sense.

According to a 1965 law, the Minister of Information and Broadcasting had control over the media. The President could also take over the GBC's operations at any time if he felt it was in the national interest. He could hire, fire, and reorganize staff as he wished.

Radio programs were a big focus for the GBC. They were designed to reach people who couldn't read. In 1961, the GBC started an international service. It broadcast in English, French, Arabic, Swahili, Portuguese, and Hausa. Using powerful transmitters, the GBC External Service broadcast 110 hours of Pan-Africanist programs to Africa and Europe each week.

Nkrumah refused advertising in all media, starting with the Evening News in 1948.

Economic Plans

The Gold Coast was one of the richest and most developed areas in Africa. It had schools, railways, hospitals, social security, and a modern economy.

Nkrumah tried to quickly make Ghana's economy industrial. He believed that if Ghana became less dependent on foreign money, technology, and goods, it could be truly independent.

After the Ten Year Development Plan, Nkrumah introduced the Second Development Plan in 1959. This plan aimed to develop manufacturing. It called for 600 factories making 100 different products.

The Statutory Corporations Act, passed in 1959 and updated later, created rules for public companies. This law put the country's main companies under the control of government ministers. The State Enterprises Secretariat was located in Flagstaff House. It was directly controlled by the president.

After visiting the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and China in 1961, Nkrumah became even more convinced that the government should control the economy.

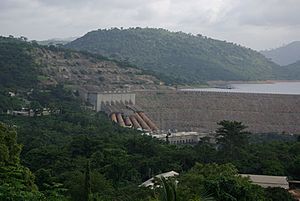

Nkrumah's early time in office was successful. Forestry, fishing, and cattle farming grew. Cocoa production, Ghana's main export, doubled. Small amounts of bauxite and gold were mined more effectively. The construction of a dam on the Volta River began in 1961. This dam provided water for farming and hydroelectric power. It produced enough electricity for towns and a new aluminum plant. Government money also went to village projects where local people built schools and roads. Free health care and education were introduced.

A Seven-Year Plan started in 1964. It focused on more industrialization. It aimed to produce goods in Ghana that were usually imported. It also focused on modernizing the building materials industry, machine making, and electronics.

Big Energy Projects

Nkrumah wanted industrial development. With help from his friend and Finance Minister, Komla Agbeli Gbedema, he started the Volta River Project. This project involved building a hydroelectric power plant, the Akosombo Dam, on the Volta River. The Volta River Project was the most important part of Nkrumah's economic plan. In 1958, he told the National Assembly that he strongly believed this project was the fastest way to economic independence. Ghana got help from the United States, Israel, and the World Bank to build the dam.

Kaiser Aluminum agreed to build the dam for Nkrumah. However, they limited what could be produced using the power. Nkrumah borrowed money to build the dam, putting Ghana in debt. To pay for this, he raised taxes on cocoa farmers in the south. This made regional differences and jealousies worse. The dam was finished and opened by Nkrumah in January 1966. This event received global attention.

Nkrumah also started the Ghana Nuclear Reactor Project in 1961. He created the Ghana Atomic Energy Commission in 1963. In 1964, he laid the first stone for an atomic energy facility.

Cocoa Farming

In 1954, the world price of cocoa rose sharply. Instead of letting cocoa farmers keep all the extra money, Nkrumah took a large part of it through government taxes. He then invested this money into various national development projects. This policy made many of his original supporters, the cocoa farmers, unhappy.

Prices continued to change. In 1960, one ton of cocoa sold for £250 in London. By August 1965, this price had dropped to £91. This was only one-fifth of its value ten years before. The quick drop in price made the government rely on its savings. It also forced farmers to take part of their earnings in government bonds.

Foreign Relations and Military

From the start of his presidency, Nkrumah actively promoted Pan-Africanism. This meant creating new international organizations. Their first meetings were held in Accra. These included:

- The First Conference of Independent States, in April 1958.

- The All-African Peoples' Conference, with representatives from 62 nationalist groups, in December 1958.

- The All-African Trade Union Federation, in November 1959, to coordinate African workers.

- The Positive Action and Security in Africa conference, in April 1960, discussing Algeria, South Africa, and French nuclear tests.

- The Conference of African Women, on 18 July 1960.

Ghana also left colonial organizations. These included West Africa Airways Corporation and the West African Currency Board.

In 1960, the "Year of Africa," Nkrumah worked to create a Union of African States. This was a political alliance between Ghana, Guinea, and Mali. A women's group called Women of the Union of African States formed immediately.

Nkrumah was a key figure in the short-lived Casablanca Group of African leaders. This group wanted to achieve African unity through strong political, economic, and military integration. This was before the Organization of African Unity (OAU) was formed.

Nkrumah was very important in creating the OAU in Addis Ababa in 1963. He wanted to create a united military force, the African High Command. Ghana would lead this force. He committed to this idea in Ghana's 1960 constitution.

He also supported the United Nations. However, he was critical of how powerful countries could control it. Nkrumah was against African states joining the Common Market of the European Economic Community. Many former French colonies and Nigeria were considering this.

Ghana's Armed Forces

In 1956, Ghana took control of the Royal West African Frontier Force (RWAFF), Gold Coast Regiment, from Britain. This force had been used to stop internal unrest and fight in wars. Most senior officers were British. Although training for African officers began in 1947, only 28 out of 212 officers were African in December 1956. British officers still received much higher salaries than their Ghanaian counterparts. Nkrumah worried about a possible military takeover. He delayed putting African officers in top leadership roles.

Nkrumah quickly set up the Ghanaian Air Force. He bought 14 Beaver airplanes from Canada. He also started a flight school with British instructors. Other planes like Otters and Caribou followed. Ghana also got four Ilyushin-18 aircraft from the Soviet Union. Training began in April 1959 with help from India and Israel.

The Ghanaian Navy received two small minesweepers from Britain in December 1959. It later received other patrol boats. The Navy's main training ship was the Achimota, a British yacht. In 1961, the Navy ordered two larger ships, the Keta and Kromantse. They received them in 1967. They also got four Soviet patrol boats. Naval officers were trained in Britain. Ghana's military budget increased every year, from $9.35 million in 1958 to $47 million in 1965.

The first time Ghanaian armed forces were sent abroad was to Congo. In 1960, Ghanaian troops were flown there at the start of the Congo crisis. One week after Belgian troops took over the rich mining province of Katanga, Ghana sent over a thousand troops to join a United Nations force. Using British officers in this situation was not acceptable. This led to a quick transfer of officer positions to Ghanaians. The Congo war was long and difficult. In January 1961, the Third Infantry Battalion rebelled. In April 1961, 43 men were killed in a surprise attack by the Congolese army.

Ghana also gave military support to rebels fighting against Ian Smith's white-minority government in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Rhodesia had declared independence from Britain in 1965.

Connections with Communist Countries

In 1961, Nkrumah toured Eastern Europe. He declared solidarity with the Soviet Union and China. Nkrumah even started wearing Chinese-supplied Mao suits.

In 1962, Kwame Nkrumah received the Lenin Peace Prize from the Soviet Union.

Overthrow from Power

In February 1966, Nkrumah was on a state visit to North Vietnam and China. While he was away, his government was overthrown. The national military and police forces led a coup d'état. The new leaders, led by Joseph Arthur Ankrah, called themselves the National Liberation Council. They ruled as a military government for three years. Nkrumah learned about the coup when he arrived in China. He stayed in Beijing for four days, and Premier Zhou Enlai treated him with respect.

After the coup, Ghana changed its international relations. It cut close ties with Guinea and Eastern European countries. It built new friendships with Western countries. The International Monetary Fund and World Bank took a leading role in managing Ghana's economy. Ghana also expelled immigrants and showed a willingness to talk with apartheid South Africa. These changes made Ghana lose some of its standing among African nationalists.

Exile, Death, and Legacy

Nkrumah never returned to Ghana. However, he continued to promote his idea of African unity. He lived in exile in Conakry, Guinea. He was a guest of President Ahmed Sékou Touré, who made him an honorary co-president. Nkrumah spent his time reading, writing, gardening, and meeting guests. Even though he was no longer in public office, he was concerned about his safety. He became ill and flew to Bucharest, Romania, for medical treatment in August 1971. He died of prostate cancer in April 1972, at the age of 62, while in Romania.

Nkrumah was first buried in his birth village, Nkroful, Ghana. Later, his remains were moved to a large national memorial tomb and park in Accra, Ghana.

Many universities gave Nkrumah honorary doctorates during his lifetime. These included Lincoln University (Pennsylvania), Moscow State University, and Cairo University.

In 2000, listeners of the BBC World Service voted him African Man of the Millennium. The BBC called him a "Hero of Independence" and an "International symbol of freedom." He was the leader of the first black African country to gain independence after World War II.

In September 2009, President John Atta Mills declared 21 September (Nkrumah's 100th birthday) as Founders' Day. This was a public holiday in Ghana to celebrate Nkrumah's legacy. In April 2019, President Akufo-Addo changed 21 September from Founders' Day to Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Day.

Nkrumah generally followed a non-aligned Marxist view on economics. He believed that capitalism had negative effects that would stay with Africa for a long time. He argued that socialism was the best system for Africa. It could handle the changes brought by capitalism while still respecting African values.

Nkrumah was also known for his strong support of pan-Africanism. He was inspired by the writings of black thinkers like Marcus Garvey, W. E. B. Du Bois, and George Padmore. He wanted to find a solution for Africa's problems. He became a passionate supporter of the "African Personality," meaning "Africa for the Africans." He believed that political independence was needed for economic independence. Nkrumah's dedication to Pan-Africanism attracted these thinkers to his projects in Ghana. Many Americans, like Du Bois and Kwame Ture, moved to Ghana to join him. His biggest success in this area was his important role in founding the Organisation of African Unity.

Nkrumah also became a symbol for black liberation in the United States.

In 1961, Nkrumah gave a speech called "I Speak Of Freedom." In this speech, he talked about how "Africa could become one of the greatest forces for good in the world." He mentioned that Africa has "vast riches" and mineral resources like gold, diamonds, uranium, and petroleum. Nkrumah said Africa was not thriving because European powers had taken its wealth. He believed that if Africa was independent, it could flourish and help the world. At the end of his speech, Nkrumah called his people to action: "This is our chance. We must act now. Tomorrow may be too late and the opportunity will have passed, and with it the hope of free Africa's survival." This speech inspired a nationalistic movement.

Personal Life

Kwame Nkrumah married Fathia Ritzk, an Egyptian Coptic bank worker and former teacher. They married on New Year's Eve, 1957–1958, the evening she arrived in Ghana. Fathia's mother did not approve of the marriage.

Kwame and Fathia Nkrumah had three children: Gamal (born 1959), Samia (born 1960), and Sekou (born 1963). Gamal is a journalist. Samia and Sekou are politicians. Nkrumah also has another son, Francis, who is a pediatrician (born 1962).

Cultural Depictions

In the 2010 book The Other Wes Moore, Nkrumah is mentioned as a mentor to the author's grandfather. This happened for several months when the author's family first moved to the United States.

Danny Sapani plays Nkrumah in the Netflix TV series The Crown (season 2, episode 8 "Dear Mrs Kennedy"). The show's depiction of the Queen's visit to Ghana and her dance with Nkrumah has been described as exaggerated by some.

African's Black Star: The Legacy of Kwame Nkrumah is a 2011 film. It tells the story of this leader who fought against colonial rule.

A golden statue of Nkrumah is featured in Ghanaian rapper Serious Klein's 2021 music video "Straight Outta Pandemic."

Works by Kwame Nkrumah

- "Negro History: European Government in Africa", The Lincolnian, 12 April 1938, p. 2 (Lincoln University, Pennsylvania)

- Ghana: The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah (1957)

- Africa Must Unite (1963)

- African Personality (1963)

- Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism (1965)

- Axioms of Kwame Nkrumah (1967)

- African Socialism Revisited (1967)

- Challenge of the Congo (1967)

- Voice From Conakry (1967)

- Dark Days in Ghana (1968)

- Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare (1968)

- Consciencism: Philosophy and Ideology for De-Colonisation (1970)

- Class Struggle in Africa (1970)

- The Struggle Continues (1973)

- I Speak of Freedom (1973)

- Revolutionary Path (1973)

Festival

For details see Kwame Nkrumah Festival

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Kwame Nkrumah para niños

In Spanish: Kwame Nkrumah para niños