British contribution to the Manhattan Project facts for kids

Britain started its own research project to build an atomic bomb in 1941. This work helped the United States understand how important this research was. Because of this, the US started its own huge project, called the Manhattan Project, in 1942. Britain played a key role by providing important scientific knowledge and help, which led to the successful completion of the project in August 1945.

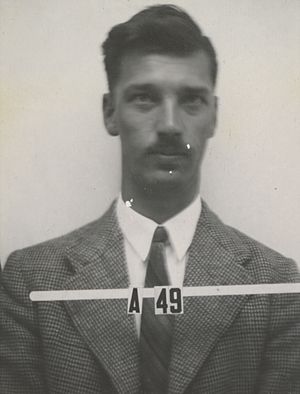

After scientists discovered something called nuclear fission in uranium, two scientists named Rudolf Peierls and Otto Frisch at the University of Birmingham figured out something amazing in March 1940. They calculated that a very small amount of pure uranium-235 (only about 1 to 10 kilograms) could explode with the power of thousands of tons of dynamite. This discovery, known as the Frisch–Peierls memorandum, pushed Britain to start its own atomic bomb project, called Tube Alloys.

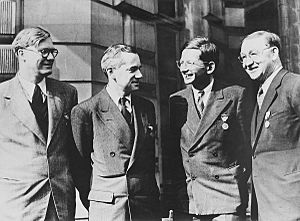

An Australian physicist working in Britain, Mark Oliphant, was very important in sharing these findings with the United States in 1941. He visited the US in person and explained the results of the British MAUD Report. At first, the British project was bigger and more advanced. However, after the United States joined World War II, the American project grew much faster and became much larger than Britain's. The British government then decided to stop its own nuclear bomb plans and join the American project instead.

In August 1943, the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, and the US President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, signed an agreement called the Quebec Agreement. This agreement allowed the two countries to work together. At this time, Britain's research into the physics needed for a bomb was more advanced. The Quebec Agreement created a Combined Policy Committee and a Combined Development Trust to help the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada work together. Another agreement, the Hyde Park Agreement in September 1944, extended this teamwork even after the war.

A British team, led by Wallace Akers, helped develop a special technology called gaseous diffusion in New York. Britain also supplied the special powdered nickel needed for this process. Another team, led by Oliphant, helped with the electromagnetic separation process at the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory. James Chadwick led the British team at the Los Alamos Laboratory. This team included many famous scientists like Sir Geoffrey Taylor, James Tuck, Niels Bohr, Peierls, Frisch, and Klaus Fuchs, who was later found to be a Soviet atomic spy. Four members of the British team became leaders of groups at Los Alamos. William Penney watched the bombing of Nagasaki and took part in the Operation Crossroads nuclear tests in 1946.

This cooperation ended with the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, also known as the McMahon Act. Ernest Titterton, the last British government employee, left Los Alamos on April 12, 1947. Britain then started its own nuclear weapons program, called High Explosive Research. In October 1952, Britain became the third country to test its own nuclear weapon.

Contents

How It Started

In 1938, scientists like Otto Robert Frisch, Fritz Strassmann, Lise Meitner, and Otto Hahn discovered nuclear fission in uranium. This discovery made people think that an incredibly powerful atomic bomb could be made. Many scientists who had fled from Nazi Germany and other fascist countries were especially worried about Germany developing such a weapon.

In the United States, three of these scientists, Leo Szilard, Eugene Wigner, and Albert Einstein, wrote a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt warning him of the danger. This led to the President creating the Advisory Committee on Uranium. In Britain, two Nobel Prize winners, George Paget Thomson and William Lawrence Bragg, were also very concerned. Their worries reached Major General Hastings Ismay, who talked to Sir Henry Tizard. Like many scientists, Tizard doubted that an atomic bomb could be built, thinking the chances were 100,000 to 1 against it.

Even with such low odds, the danger was serious enough to be taken seriously. Thomson, at Imperial College London, and Mark Oliphant, an Australian physicist at the University of Birmingham, were asked to do experiments on uranium. By February 1940, Thomson's team hadn't been able to create a chain reaction in natural uranium, and he thought it wasn't worth continuing.

But at Birmingham, Oliphant's team reached a very different conclusion. Oliphant had given the task to two German refugee scientists, Rudolf Peierls and Otto Frisch. They couldn't work on the University's radar project because they were considered "enemy aliens" and didn't have the necessary security clearance. They calculated the critical mass of pure uranium-235, which is the only type of uranium that easily splits apart. They found that instead of tons, as everyone had thought, as little as 1 to 10 kilograms would be enough. This small amount could explode with the power of thousands of tons of dynamite.

Oliphant took this Frisch–Peierls memorandum to Tizard, and the MAUD Committee was set up to investigate further. This committee started intense research. In July 1941, they produced two detailed reports. These reports concluded that an atomic bomb was not only possible to build, but it could also be ready before the war ended, possibly in as little as two years. The committee strongly recommended developing an atomic bomb quickly, even though they knew Britain might not have enough resources. A new group called Tube Alloys was created to manage this effort. Sir John Anderson, a government minister, became responsible for it, and Wallace Akers from Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) was chosen to lead Tube Alloys.

Working Together

Early Cooperation

In July 1940, Britain offered to share its scientific research with the United States. John Cockcroft of the Tizard Mission told American scientists about Britain's progress. He found that the American project was smaller and less advanced than Britain's. The findings of the Maud Committee were shared with the US. Oliphant, a member of the Maud Committee, flew to the United States in August 1941. He found that important information hadn't reached key American physicists. He met with the Uranium Committee and visited Berkeley, California. There, he spoke convincingly to Ernest O. Lawrence, who was so impressed that he started his own uranium research at the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory.

Oliphant's trip was a success. Important American physicists learned about the atomic bomb's potential power. With the British data, Vannevar Bush, who led the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), informed President Roosevelt and Vice President Henry A. Wallace in a meeting on October 9, 1941.

Britain and America exchanged nuclear information, but they didn't immediately combine their efforts. British officials didn't respond to an offer in August 1941 to create a joint project. In November 1941, Frederick L. Hovde, from the OSRD's London office, brought up the idea of cooperation. Anderson and Lord Cherwell hesitated, saying they were worried about American security. Ironically, the British project had already been secretly infiltrated by atomic spies working for the Soviet Union.

However, the United Kingdom didn't have as many people or resources as the United States. Despite its strong start, Tube Alloys fell behind the American project and was dwarfed by it. Britain was spending about £430,000 per year on research. The Manhattan Project, however, was spending £8,750,000 on research and had construction contracts worth £100,000,000. On July 30, 1942, Anderson told Prime Minister Winston Churchill that Britain's early work was becoming less important. He said that unless they used it quickly, they would be left behind.

By then, the roles of the two countries had switched. The Americans became suspicious that the British wanted commercial benefits after the war. Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves Jr., who took over the Manhattan Project in September 1942, wanted to keep information very secret. American officials decided they no longer needed outside help. The Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, felt that since the US was doing "ninety percent of the work," it was "better for us to go along for the present without sharing anything more than we could help." In December 1942, Roosevelt agreed to limit information sharing to only what Britain could use during the war, even if it slowed down the American project. In response, the British stopped sending information and scientists to America, and the Americans then stopped all information sharing.

The British thought about how they would build a bomb without American help. Building a plant to produce 1 kilogram of weapons-grade uranium per day was estimated to cost up to £50,000,000. A nuclear reactor to produce 1 kilogram of plutonium per day would have to be built in Canada. It would take up to five years and cost £5,000,000. This huge project would need 20,000 workers, 500,000 tons of steel, and a lot of electricity. It would disrupt other wartime projects and likely wouldn't be ready in time to affect the war in Europe. Everyone agreed that before starting this, they should try one more time to get American cooperation.

Cooperation Starts Again

By March 1943, Conant decided that British help would be useful for some parts of the project. The Manhattan Project could especially benefit from the help of James Chadwick, who discovered the neutron, and other British scientists. Bush, Conant, and Groves wanted Chadwick and Peierls to discuss bomb design with Robert Oppenheimer.

Churchill discussed the matter with Roosevelt at the Washington Conference on May 25, 1943. Churchill thought Roosevelt gave him the assurances he wanted, but nothing happened afterward. Bush, Stimson, and William Bundy met Churchill, Cherwell, and Anderson in London. None of them knew that Roosevelt had already made his decision. Roosevelt had written to Bush on July 20, 1943, instructing him to "renew, in an inclusive manner, the full exchange with the British Government regarding Tube Alloys."

Stimson, who had just argued with the British about the need for an invasion of France, didn't want to disagree with them on everything. He spoke kindly about the need for good post-war relations. Churchill, for his part, said he wasn't interested in making money from nuclear technology after the war. Cherwell explained that Britain's concern about post-war cooperation was not about money, but about having nuclear weapons after the war. Anderson then wrote an agreement for full exchange, which Churchill rephrased in "more majestic language." News of Roosevelt's decision arrived in London on July 27, and Anderson was sent to Washington with the draft agreement. Churchill and Roosevelt signed the Quebec Agreement at the Quebec Conference on August 19, 1943.

The Quebec Agreement created the Combined Policy Committee to coordinate the efforts of the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada. Stimson, Bush, and Conant were the American members. Sir John Dill and Colonel John Jestyn Llewellin were the British members, and C. D. Howe was the Canadian member.

Even before the Quebec Agreement was signed, Akers had already told London that Chadwick, Peierls, Oliphant, and Francis Simon should leave immediately for North America. They arrived on August 19, the day the agreement was signed. They expected to talk to American scientists, but couldn't. It took two weeks for American officials to learn about the Quebec Agreement's contents. Over the next two years, the Combined Policy Committee met only eight times.

The first meeting was on September 8, 1943. It set up a Technical Subcommittee led by Major General Wilhelm D. Styer. Because the Americans didn't want Akers on this committee, Llewellin nominated Chadwick, who also became the Head of the British Mission to the Manhattan Project. It was agreed that the Technical Committee could make decisions without asking the Combined Policy Committee if everyone agreed.

Chadwick fully supported British involvement in the Manhattan Project, giving up any hopes of a separate British project during the war. With Churchill's support, he tried to make sure that every request from Groves for help was met.

The Hyde Park Agreement in September 1944 extended cooperation for both commercial and military purposes into the post-war period. The Quebec Agreement stated that nuclear weapons would not be used against another country without both sides agreeing. On July 4, 1945, Wilson agreed that the use of nuclear weapons against Japan would be recorded as a decision of the Combined Policy Committee.

Gaseous Diffusion Project

Tube Alloys made its biggest progress in gaseous diffusion technology. Chadwick had hoped that at least a small pilot plant would be built in Britain. This technology was developed by Simon and three other scientists in 1940. Prototype equipment was made by Metropolitan-Vickers.

The Quebec Agreement allowed Simon and Peierls to meet with the American companies designing and building the US gaseous diffusion plant. The loss of cooperation for a year cost the Manhattan Project a lot. The companies were working on tight schedules, and engineers couldn't easily add British ideas that would require big changes. Still, the Americans were eager for British help, and Groves asked for a British team to assist the gaseous diffusion project. Simon and Peierls worked with the American company, Kellex.

A British team of fifteen experts arrived in December 1943. This was a critical time. There were serious problems with a part called the Norris-Adler barrier. A decision had to be made whether to keep working on it or switch to a new barrier based on British technology. The British experts reviewed everything and agreed that the new Kellex barrier was better, but they thought it wouldn't be ready in time. Kellex's technical director disagreed, saying his company could get it ready faster. Groves listened to the British experts before officially choosing the Kellex barrier on January 5, 1944.

The US Army was in charge of getting enough of the right type of powdered nickel. Here, the British were able to help. The only company that made it was the Mond Nickel Company in Clydach, Wales. By the end of June 1945, it had supplied the Manhattan Project with 5,000 long tons of nickel powder. This was paid for by the British government and given to the United States as part of a wartime aid program.

The Americans planned to have their K-25 plant fully working by June or July 1945. The British experts thought this was very optimistic, as it had taken two years to get the prototype stages working. They felt it wouldn't be ready before the end of 1946. This opinion upset their American colleagues and reduced the desire for cooperation. The British team returned to the United Kingdom in January 1944. Despite the British team's pessimistic predictions, K-25 was producing enriched uranium in June 1945.

After the rest of the team left, Peierls, Kurti, and Fuchs stayed in New York and worked with Kellex. They were joined by Tony Skyrme and Frank Kearton. Peierls later moved to the Los Alamos Laboratory in February 1944, followed by Skyrme and Fuchs.

Electromagnetic Project

In May 1943, Oliphant thought he had found a better way for electromagnetic isotope separation than Lawrence's method. His idea was reviewed and found to be good. While most scientists in Britain preferred the gaseous diffusion method, electromagnetic separation might still be useful as a final step to make uranium even purer. So, Oliphant was allowed to leave the radar project to work on Tube Alloys, doing experiments at the University of Birmingham.

Oliphant met Groves and Oppenheimer in Washington, D.C., in September 1943. They tried to convince him to join the Los Alamos Laboratory, but Oliphant felt he would be more useful helping Lawrence with the electromagnetic project. So, Oliphant and six assistants went to Berkeley. Oliphant found that he and Lawrence had different designs, and the American one was already set. But Lawrence was eager for Oliphant's help. Oliphant brought in other scientists, and the British team at Berkeley grew to 35 people.

Members of the British team held important positions in the electromagnetic project. Oliphant became Lawrence's unofficial second-in-command and was in charge of the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory when Lawrence was away. His excitement for the project was almost as great as Lawrence's. British chemists also made important contributions. The British team had full access to the electromagnetic project, both in Berkeley and at the Y-12 plant in Oak Ridge. Most of the British team stayed until the end of the war. Oliphant returned to Britain in March 1945, and Harrie Massey replaced him as head of the British team in Berkeley.

Los Alamos Laboratory

When cooperation restarted in September 1943, Groves and Oppenheimer told Chadwick, Peierls, and Oliphant about the Los Alamos Laboratory. Oppenheimer wanted all three to go to Los Alamos as soon as possible. However, it was decided that Oliphant would go to Berkeley for the electromagnetic process, and Peierls would go to New York for the gaseous diffusion process. So, the task fell to Chadwick. The original idea was for British scientists to work as a group under Chadwick, but this was changed. Instead, the British team was fully integrated into the laboratory. They worked in most of its divisions, only being excluded from plutonium chemistry and metallurgy.

The first to arrive were Otto Frisch and Ernest Titterton with his wife Peggy, who reached Los Alamos on December 13, 1943. Frisch continued his work on critical mass studies, and Titterton developed electronic circuits for the bomb. Peggy Titterton, a skilled physics and metallurgy lab assistant, was one of the few women in a technical role at Los Alamos. Chadwick arrived on January 12, 1944, but only stayed a few months before returning to Washington, D.C.

When Oppenheimer appointed Hans Bethe to lead the laboratory's Theoretical (T) Division, Edward Teller was upset. Teller was given his own group to research the "Super" bomb. Oppenheimer then asked Groves to send Peierls to take Teller's place in T Division. Peierls arrived from New York on February 8, 1944, and later took over from Chadwick as head of the British Mission at Los Alamos. Four members of the British team became group leaders: Bretscher, Frisch, Peierls, and George Placzek.

Niels Bohr and his son Aage arrived on December 30 for the first of several visits as consultants. Bohr and his family had escaped from occupied Denmark to Sweden. He was flown to England where he joined Tube Alloys. In America, he visited Oak Ridge and Los Alamos, where he found many of his former students. Bohr helped by offering ideas, making things easier, and being a role model for younger scientists. He arrived at a crucial time, and many nuclear fission studies were done because of his suggestions. He played an important part in developing the uranium tamper and in designing the modulated neutron initiator. His presence boosted morale and helped improve how the laboratory was run.

Nuclear physicists knew about fission, but not much about how regular explosions worked. So, two people joined the team who greatly helped in this area. First was James L. Tuck, an expert in shaped charges used in anti-tank weapons. Scientists at Los Alamos were struggling with the idea of implosion for the plutonium bomb. Tuck was sent to Los Alamos in April 1944 and introduced a new idea called explosive lensing, which was then used. Tuck also designed the Urchin initiator for the bomb. This work was vital for the success of the plutonium atomic bomb. The other expert was Sir Geoffrey Taylor, who arrived a month later to also work on this issue. Taylor's help was so desired that Chadwick said "anything short of kidnapping would be justified" to get him there. He was sent and provided important insights into how explosions behave. The great need for scientists who understood explosives also led Chadwick to get William Penney from the Admiralty. Peierls and Fuchs worked on the hydrodynamics of the explosive lenses. Bethe considered Fuchs "one of the most valuable men in my division."

William Penney worked on how to figure out the effects of a nuclear explosion. He wrote a paper on what height the bombs should explode for the greatest effect on Germany and Japan. He was part of the committee that chose Japanese cities for atomic bombing. He also served as a special consultant on Tinian with Project Alberta. Along with Group Captain Leonard Cheshire, he watched the bombing of Nagasaki from an observation plane. He also joined the Manhattan Project's post-war scientific team that went to Hiroshima and Nagasaki to see the damage caused by the bombs.

Bethe said that the help from the British Mission was "absolutely essential" for the work of the theoretical division at Los Alamos. He believed that without them, the work would have been much harder and less effective, and the final weapon might have been less efficient.

From December 1945, members of the British Mission started returning home. Peierls left in January 1946. At the request of Norris Bradbury, who replaced Oppenheimer as laboratory director, Fuchs stayed until June 15, 1946. Eight British scientists participated in Operation Crossroads, the nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific. With the passing of the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, all British government employees had to leave. Titterton was given special permission and stayed until April 12, 1947. The British Mission ended when he left. Carson Mark, a Canadian government employee, remained at Los Alamos and became head of its Theoretical Division in 1947.

Raw Materials

The Combined Development Trust was suggested in February 1944. The agreement was signed by Churchill and Roosevelt on June 13, 1944. Its purpose was to buy or control the mineral resources needed by the Manhattan Project and prevent the three countries from competing against each other. Britain didn't need much uranium ore during the war, but it wanted to secure enough supplies for its own nuclear weapons program after the war. Half the funding came from the United States and half from Britain and Canada.

Britain took the lead in talks to reopen the Shinkolobwe mine in the Belgian Congo. This was the world's richest source of uranium ore. The mine had been flooded and closed, but 30 percent of the company that owned it was controlled by British interests. Sir John Anderson and Ambassador John Winant made a deal in May 1944 with the mine's director and the Belgian government. The mine was reopened, and 1,720 long tons of ore were bought. The Combined Development Trust also made deals with Swedish companies to get ore from there. Oliphant also talked to the Australian High Commissioner in London about uranium supplies from Australia. Anderson directly asked the Prime Minister of Australia, John Curtin, in May 1944 to start looking for uranium deposits in Australia. Besides uranium, the Trust also secured supplies of thorium from other countries. At the time, uranium was thought to be rare, and thorium was seen as a possible alternative because it could be used to produce uranium-233, another type of uranium suitable for making atomic bombs.

Intelligence

In December 1943, Groves sent Robert R. Furman to Britain to set up a London office for the Manhattan Project. This office would coordinate scientific intelligence with the British government. An Anglo-American intelligence committee was formed by Groves and Anderson in November 1944.

At the urging of Groves and Furman, the Alsos Mission was created in April 1944. This mission, led by Lieutenant Colonel Boris Pash, was to gather intelligence about the German nuclear energy project. The more experienced British thought about creating their own mission, but eventually agreed to join the Alsos Mission as a junior partner. In June 1945, Eric Welsh reported that the German nuclear physicists captured by the Alsos Mission were in danger. So, they were moved to Farm Hall, a country house in England used for training. The house was secretly bugged, and the scientists' conversations were recorded.

What Happened Next

Groves appreciated the early British atomic research and the British scientists' help. However, he stated that the United States would have succeeded without them. He thought British assistance was "helpful but not vital." Still, he admitted that "without active and continuing British interest, there probably would have been no atomic bomb to drop on Hiroshima." He believed Britain's main contributions were encouragement, scientific help, the production of powdered nickel in Wales, and early studies.

Cooperation didn't last long after the war. Roosevelt died in April 1945, and the Hyde Park Agreement was not legally binding on future governments. In fact, the physical copy of the agreement was lost. When Wilson brought it up in a meeting in June, the American copy couldn't be found. The British sent Stimson a photocopy in July 1945. Even then, Groves doubted the document's authenticity until the American copy was found years later.

Harry S. Truman (who became President after Roosevelt), Clement Attlee (who replaced Churchill as prime minister in July 1945), Anderson, and United States Secretary of State James F. Byrnes met on a boat. They agreed to change the Quebec Agreement. On November 15, 1945, they agreed to keep the Combined Policy Committee and the Combined Development Trust. The Quebec Agreement's rule that nuclear weapons couldn't be used without "mutual consent" was changed to "prior consultation." There was supposed to be "full and effective cooperation in the field of atomic energy," but in a longer document, this was only "in the field of basic scientific research." Truman and Attlee signed it on November 16, 1945.

The next meeting of the Combined Policy Committee in April 1946 didn't lead to an agreement on working together. Truman cabled on April 20 that he didn't see the agreement he signed as forcing the US to help Britain build and operate an atomic energy plant. Attlee's response in June 1946 was very clear about his displeasure. The issue wasn't just technical cooperation, which was quickly disappearing, but also the sharing of uranium ore. During the war, this wasn't a concern because Britain didn't need any ore. All the ore from the Congo mines went to the United States. But now, the British atomic project also needed it. Chadwick and Groves reached an agreement to share the ore equally.

The McMahon Act, signed by Truman on August 1, 1946, and effective on January 1, 1947, ended technical cooperation. This law prevented the United States' allies from receiving any information. The remaining scientists were denied access to papers they had written just days before. The terms of the Quebec Agreement remained secret, but members of Congress were shocked when they found out it gave the British a veto over the use of nuclear weapons. The McMahon Act caused anger among British scientists and officials. This directly led to Britain's decision in January 1947 to develop its own nuclear weapons. In January 1948, an agreement called the modus vivendi allowed for limited sharing of technical information between the United States, Britain, and Canada.

As the Cold War began, enthusiasm in the United States for an alliance with Britain also cooled. A poll in September 1949 found that 72 percent of Americans agreed that the United States should not "share our atomic energy secrets with England." The reputation of the British Mission to Los Alamos was damaged in 1950 when it was revealed that Fuchs was a Soviet atomic spy. This hurt the relationship between the United States and Britain.

Britain's participation in the Manhattan Project during the war provided a lot of knowledge that was crucial for the success of High Explosive Research, the United Kingdom's post-war nuclear weapons program. However, there were some gaps in their knowledge. The development of Britain's own nuclear deterrent led to the Atomic Energy Act being changed in 1958. This also led to a return of the nuclear Special Relationship between America and Britain under the 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement.

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |