Leo Szilard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Leo Szilard

|

|

|---|---|

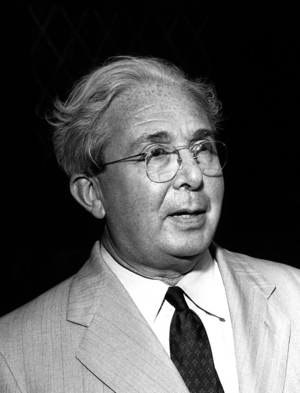

Szilard, c. 1960

|

|

| Born |

Leó Spitz

February 11, 1898 |

| Died | May 30, 1964 (aged 66) San Diego, California, U.S.

|

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics, biology |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Über die thermodynamischen Schwankungserscheinungen (1923) |

| Doctoral advisor | Max von Laue |

| Other academic advisors | Albert Einstein |

| Signature | |

Leo Szilard (born Leó Spitz; February 11, 1898 – May 30, 1964) was a brilliant scientist and inventor. He was Hungarian, German, and later American. He is famous for coming up with the idea of a nuclear chain reaction in 1933. This idea was key to developing nuclear reactors and atomic bombs. In 1939, he helped write a letter for Albert Einstein to sign. This letter led to the Manhattan Project, which built the first atomic bombs. Szilard was also one of the group of smart Hungarian scientists known as "The Martians."

Contents

Early Life and Education

Leo Szilard was born in Budapest, Hungary, on February 11, 1898. His family changed their last name from Spitz to Szilárd, which means "solid" in Hungarian. From a young age, he loved physics and was very good at math. In 1916, he won a national math prize.

He started studying engineering in Budapest. But his studies were stopped by World War I, when he joined the Austro-Hungarian Army. He got sick with the Spanish Flu, which probably saved his life, as his army unit was almost destroyed in battle.

After the war, Hungary was in a difficult political situation. Szilard felt there was no future for him there. So, in 1919, he moved to Berlin, Germany. He first studied engineering but soon became more interested in physics. He transferred to Friedrich Wilhelm University to study physics. There, he attended lectures by famous scientists like Albert Einstein and Max Planck.

In 1922, Szilard earned his doctorate. His thesis was about thermodynamics, a field of physics that deals with heat and energy. Einstein praised his work. Szilard was one of the first to see a link between thermodynamics and information theory.

Inventions and Discoveries

While in Berlin, Szilard worked on many inventions. In 1928, he applied for a patent for the linear accelerator. He also came up with the idea for the electron microscope and applied for its first patent in 1928. In 1929, he applied for a patent for the cyclotron.

Between 1926 and 1930, he worked with Albert Einstein to create the Einstein refrigerator. This refrigerator was special because it had no moving parts. Szilard didn't always build these devices or publish his ideas in science papers. Because of this, other scientists often got credit for these inventions later on. For example, Ernest Lawrence won a Nobel Prize for the cyclotron, and Ernst Ruska for the electron microscope.

In 1933, Adolf Hitler became the leader of Germany. Szilard was worried about the future in Europe. He told his family and friends to leave if they could. He moved to England and helped start the Council for Assisting Refugee Academics. This group helped scientists who had to flee their homes find new jobs.

While in England, Szilard made a very important discovery. He read a newspaper article where a famous scientist, Ernest Rutherford, said that using atomic energy for practical things was impossible. Szilard disagreed. On September 12, 1933, he had an amazing idea: the nuclear chain reaction. He realized that if a nuclear reaction could produce energy and also create more neutrons (tiny particles), then the reaction could keep going by itself. This would release a huge amount of energy.

He filed a patent for this idea in 1933. To keep it secret, he assigned the patent to the British government. He had read a book by H. G. Wells called The World Set Free, which described "atomic bombs." Szilard knew how powerful his idea could be and wanted to keep it from falling into the wrong hands.

He also discovered a way to separate different types of isotopes (versions of an element) for medical uses. This method is called the Szilard–Chalmers effect.

The Manhattan Project

Moving to the United States

Szilard believed another war in Europe was coming. So, in 1938, he moved to the United States. He worked with other scientists like Enrico Fermi and Walter Zinn to figure out how to create a nuclear chain reaction.

In January 1939, news arrived in New York about the discovery of nuclear fission in Germany. This meant that splitting a uranium atom could release energy. Szilard immediately realized that uranium could be the element to sustain a chain reaction.

He and Walter Zinn did a simple experiment at Columbia University. They bombarded uranium with neutrons and saw that the uranium produced more neutrons than it absorbed. This showed that a chain reaction was possible! Szilard later said, "That night, there was very little doubt in my mind that the world was headed for grief." He understood the huge power this discovery could unleash.

Szilard then suggested using carbon (in the form of graphite) to slow down the neutrons, which would help the chain reaction. He also made a crucial discovery: he found that normal graphite contained boron, which absorbs neutrons. He made sure to get special boron-free graphite. If he hadn't, the project might have failed, just like similar efforts in Germany.

The Einstein–Szilárd Letter

Szilard was worried that Nazi Germany might develop nuclear weapons first. He drafted a secret letter to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The letter explained the possibility of nuclear weapons and urged the U.S. to start its own research program. With the help of other scientists, he convinced his old friend Albert Einstein to sign the letter in August 1939. Einstein's fame gave the letter more weight.

This letter, known as the Einstein–Szilárd letter, led to the U.S. government starting research into nuclear fission. This research eventually became the top-secret Manhattan Project, which built the first atomic bombs during World War II.

Working on the Atomic Bomb

In 1942, Szilard joined the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago. This was a key part of the Manhattan Project. He was a chief physicist and often asked important questions that helped the project. He helped improve how uranium was processed and how nuclear reactors should be cooled.

On December 2, 1942, Szilard was present when the first human-made, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was achieved. This happened in the Chicago Pile-1, the first nuclear reactor, built under a stadium at the University of Chicago. He shook Enrico Fermi's hand, marking a historic moment.

Szilard became a U.S. citizen in 1943. He and Fermi held the patent for the nuclear reactor. He sold his patent to the government for a small fee, wanting to help the war effort.

Szilard deeply cared about human life and freedom. He hoped that the atomic bomb would not be used, but that its threat would make Germany and Japan surrender. He also worried about the long-term dangers of nuclear weapons, predicting a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union. He wrote the Szilárd petition, asking for a demonstration of the atomic bomb before using it on cities. However, the U.S. government decided to use the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki without warning. After the war, he worked to put nuclear energy under civilian control.

Life After the War

Shift to Biology

After World War II, Szilard changed his focus from physics to biology. He became a research professor at the University of Chicago in 1946. He believed biology was a field ready for big discoveries.

He and his colleague Aaron Novick made important advances. They invented the chemostat, a device to control how microorganisms grow. They also discovered feedback inhibition, a key process in how living things grow and use energy. Szilard also gave important advice for the first successful cloning of a human cell in 1955.

Advocacy for Peace

Szilard was very concerned about the dangers of nuclear weapons. He publicly warned about the possibility of "salted thermonuclear bombs," a new type of nuclear weapon that could potentially wipe out humanity. He wrote a book of short stories called The Voice of the Dolphins (1961). In this book, he explored the moral questions raised by the Cold War and his own role in creating atomic weapons.

In 1962, Szilard founded the Council for a Livable World. This group aimed to speak "the sweet voice of reason" about nuclear weapons to leaders in government and the public. He wanted to prevent a nuclear war.

Later Years and Legacy

In 1960, Szilard was diagnosed with bladder cancer. He helped design his own cobalt therapy treatment, which successfully cured him.

He spent his last years as a fellow at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego, California, which he helped create. Leo Szilard died in his sleep from a heart attack on May 30, 1964.

Szilard received many honors for his work, including the Atoms for Peace Award in 1959. A crater on the Moon and an asteroid are named after him. The Leo Szilard Lectureship Award is given in his honor by the American Physical Society. His ideas and warnings about nuclear weapons continue to be important today.

Patents

- , GB 630726—Improvements in or relating to the transmutation of chemical elements—L. Szilard, filed June 28, 1934

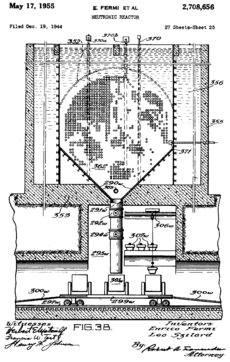

- U.S. Patent 2,708,656—Neutronic reactor—E. Fermi, L. Szilard, filed December 19, 1944, issued May 17, 1955

- U.S. Patent 1,781,541—Einstein Refrigerator—co-developed with Albert Einstein filed in 1926, issued November 11, 1930

Recognition and Remembrance

- Atoms for Peace Award, 1959

- Albert Einstein Award, 1960

- American Humanist Association's Humanist of the Year, 1960

- Szilard (crater) on the far side of the Moon, named in 1970

- Leo Szilard Lectureship Award, since 1974

- Asteroid 38442 Szilárd discovered in 1999

- Leószilárdite, mineral, reported in 2016

See also

In Spanish: Leó Szilárd para niños

In Spanish: Leó Szilárd para niños

- The Martians (scientists)

Images for kids

-

Szilard and Norman Hilberry at the site of CP-1, at the University of Chicago, some years after the war. It was demolished in 1957.

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |