Mark Oliphant facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mark Oliphant

|

|

|---|---|

Oliphant in 1939

|

|

| Born |

Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant

8 October 1901 Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

|

| Died | 14 July 2000 (aged 98) Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia

|

| Alma mater | |

| Known for |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | The Neutralization of Positive Ions at Metal Surfaces, and the Emission of Secondary Electrons (1929) |

| Doctoral advisor | Ernest Rutherford |

| Doctoral students |

|

| 27th Governor of South Australia | |

| In office 1 December 1971 – 30 November 1976 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Premier | Don Dunstan |

| Lieutenant Governor |

|

| Preceded by | Sir James Harrison |

| Succeeded by | Sir Douglas Nicholls |

Sir Mark Oliphant (born October 8, 1901 – died July 14, 2000) was an amazing Australian scientist and a kind person. He was very important in showing how nuclear fusion works and in creating nuclear weapons.

Mark was born and grew up in Adelaide, South Australia. He finished his studies at the University of Adelaide in 1922. Later, he went to England to study under Sir Ernest Rutherford at the University of Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory. There, he used a special machine called a particle accelerator to shoot tiny particles at different targets. He discovered the nuclei of helium-3 and tritium. He also found that when these particles reacted, they released a lot more energy than they started with. This was a big discovery: energy was coming from inside the atom's core, which he called nuclear fusion.

In 1937, Oliphant moved to the University of Birmingham. He started building a huge cyclotron (another type of particle accelerator), but World War II began in 1939, delaying its completion. During the war, he helped develop radar. His team created a new device called the cavity magnetron, which made microwave radar possible. This was a huge help in the war. Oliphant also played a key role in starting what became the Manhattan Project in the United States, which built the first atomic bomb. He worked on separating special materials needed for the bomb.

After the war, Oliphant returned to Australia. He became the first director of the Research School of Physical Sciences and Engineering at the new Australian National University (ANU). He also helped design and build the world's largest homopolar generator, a massive machine that creates huge amounts of electrical current. He retired in 1967 but then became the Governor of South Australia from 1971 to 1976. He was the first governor born in South Australia. He also helped start the Australian Democrats political party. Mark Oliphant passed away in Canberra in 2000.

Contents

Early life and education

Marcus "Mark" Laurence Elwin Oliphant was born on October 8, 1901, in Kent Town, South Australia, a suburb of Adelaide. His father, Harold George Olifent, worked for the water department and taught economics part-time. His mother, Beatrice Edith Fanny Oliphant, was an artist. Mark was named after famous authors. Most people called him Mark, and this became his official name later. He had four younger brothers.

Mark became a vegetarian when he was a boy after seeing pigs being slaughtered on a farm. He was also completely deaf in one ear and needed glasses because he was very short-sighted.

He went to primary schools in Goodwood and Mylor. For high school, he attended Unley High School and then Adelaide High School. After finishing school, he couldn't get a scholarship for university. So, he worked for a jewelry company and then got a job at the State Library of South Australia. This job allowed him to take classes at the University of Adelaide at night.

In 1919, Mark started studying at the University of Adelaide. He was first interested in medicine but then switched to physics. He got his Bachelor of Science degree in 1921. He continued his studies, working with Professor Roy Burdon on the properties of mercury. Mark later said that Burdon taught him how exciting it was to make even small discoveries in physics.

On May 23, 1925, Mark married Rosa Louise Wilbraham, who he had known since they were teenagers. He even made Rosa's wedding ring himself in the laboratory from a gold nugget.

Discoveries at Cavendish Laboratory

In 1925, Mark Oliphant heard a speech by the famous physicist Sir Ernest Rutherford. Mark decided he wanted to work for Rutherford, and he achieved this goal in 1927 when he joined the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge. He received a special scholarship that helped him live and study there.

Rutherford's Cavendish Laboratory was a leading place for nuclear physics research. Mark met many other brilliant scientists there, including James Chadwick and John Cockcroft. The lab didn't have a lot of money, so scientists often had to be creative with their equipment. Mark even bought his own vacuum pump.

In 1929, Oliphant finished his PhD. He then received another scholarship, which allowed him to continue his research for three more years.

Mark and Rosa had a son, Geoffrey, in 1930, but he sadly died of meningitis in 1933. Later, they adopted a son, Michael, in 1936, and a daughter, Vivian, in 1938.

In the early 1930s, scientists at the Cavendish Laboratory made huge breakthroughs. Cockcroft and Walton changed lithium into helium using high-energy particles. This was one of the first times an element's core was changed artificially. Chadwick then discovered the neutron, a new particle with no charge.

Oliphant built a particle accelerator that could shoot protons with very high energy. He confirmed the results of Cockcroft and Walton. In 1933, he received some heavy water from an American chemist. Using his accelerator, he shot heavy hydrogen nuclei (called deuterons) at different targets. Working with Rutherford, Oliphant discovered the nuclei of helium-3 and tritium.

Mark Oliphant was the first to show nuclear fusion in an experiment. He found that when deuterons reacted with helium-3, tritium, or other deuterons, the particles released had much more energy than they started with. This energy came from inside the atom's core. Following a prediction by Arthur Eddington in 1920, Oliphant thought that nuclear fusion might be the process that powers the sun. The fusion reaction he studied later became the basis for the hydrogen bomb.

In 1937, Oliphant was elected to the Royal Society, a very important scientific group. He was its longest-serving member when he passed away.

University of Birmingham and World War II

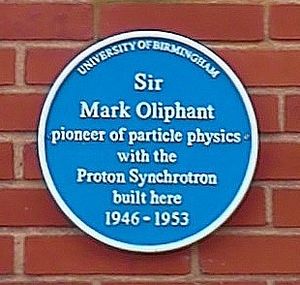

In 1937, Mark Oliphant became the Poynting Professor of Physics at the University of Birmingham. The university wanted to become a leader in nuclear physics and was willing to spend a lot of money to attract top scientists like Oliphant. He asked for a good salary and significant funds to improve the laboratory.

Oliphant wanted to build a large 60-inch (150 cm) cyclotron. He wrote to the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, who helped him get £60,000 from Lord Nuffield for the project. This money covered the cyclotron, a new building, and a trip to California for Oliphant to meet Ernest Lawrence, who invented the cyclotron. Lawrence shared his plans and invited Oliphant to visit. Oliphant hoped the cyclotron would be ready by Christmas 1939, but World War II stopped these plans. The Nuffield Cyclotron was only finished after the war.

Radar development

In 1938, Oliphant started working on radar, which was a secret project at the time. He realized that radar needed shorter radio waves to be small enough for aircraft. He got money from the British Navy to develop radar systems with very short wavelengths.

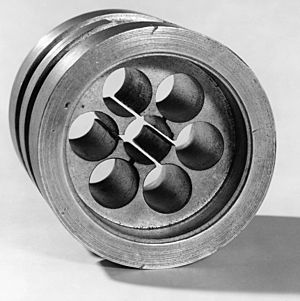

Oliphant's team at Birmingham worked on two devices: the klystron and the magnetron. Two members of his team, John Randall and Harry Boot, created a new design called the cavity magnetron. By February 1940, they had a powerful magnetron that produced the short waves needed for good airborne radars. This invention was a major scientific breakthrough during the war. It helped defeat German U-boats, intercept enemy bombers, and guide Allied bombers.

In 1940, with the war getting worse, Oliphant sent his wife and children to Australia for safety. In 1942, he also went to Australia to help develop radar there. He worked with other Australian scientists to build cavity magnetrons. Over 2,000 radar sets were made in Australia during the war.

Role in the Manhattan Project

In March 1940, two scientists, Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls, wrote a paper about building an atomic bomb. They calculated that a small amount of a special type of uranium could create a huge explosion. They showed their paper to Oliphant, who immediately took it to a government committee. This led to the creation of the MAUD Committee, which included Oliphant. In July 1941, the committee reported that an atomic bomb was possible and could be built by 1943.

Britain was at war and saw the atomic bomb as urgent, but the United States was less concerned. Oliphant was crucial in getting the American project started. In August 1941, he flew to the United States. He found that the American committee had put the MAUD report in a safe and hadn't shared it.

Oliphant met with the American Uranium Committee. He told them clearly that they must focus all their efforts on building the bomb. He explained that Britain didn't have enough money or people, so it was up to the US. He then visited his friend Lawrence in California and gave him a copy of the Frisch–Peierls memorandum. Lawrence then brought Robert Oppenheimer into the project. Oliphant convinced Lawrence and Oppenheimer that an atomic bomb was possible. He also inspired Lawrence to turn his cyclotron into a giant machine for separating uranium, a technique Oliphant had developed earlier.

Leo Szilard, another scientist, later said that Oliphant deserved a special medal for his important role in starting the atomic energy project in the US.

In 1943, Oliphant returned to the US as part of the British team working on the Manhattan Project. He worked with Lawrence at the Radiation Laboratory in Berkeley, California. He helped develop the method for separating uranium, which was a key part of the atomic bomb used in Hiroshima.

Oliphant also tried to involve other Australian scientists in the project. He briefed the Australian High Commissioner in the UK about the project and urged the Australian government to secure uranium deposits in Australia.

In September 1944, Oliphant met with Leslie Groves, the director of the Manhattan Project. He realized that the Americans planned to control nuclear weapons after the war and wouldn't share the technology with Britain or Australia. Oliphant returned to England in March 1945.

He was on holiday when he heard about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He later said he felt "proud that the bomb had worked, and absolutely appalled at what it had done to human beings." Oliphant became a strong critic of nuclear weapons and worked to control them.

Later years in Australia

In April 1946, the Australian Prime Minister, Ben Chifley, asked Oliphant to be an advisor to the Australian team at the new United Nations Atomic Energy Commission. This group was discussing how to control nuclear weapons internationally, but they couldn't reach an agreement.

Chifley also asked Oliphant to help create a new research institute in Australia to attract top scientists and improve university education. Oliphant accepted and returned to Australia in 1950. He became the first Director of the Research School of Physical Sciences and Engineering at the Australian National University (ANU).

Within the school, he created several departments, including Particle Physics, Nuclear Physics, and Astronomy.

Oliphant believed that Britain needed to develop its own nuclear weapons to remain a strong country. He also hoped that Britain would help Australia with its nuclear program, especially since Australia had uranium. However, close cooperation was difficult due to security concerns with the United States.

Oliphant imagined Canberra becoming a "university town" like Oxford or Cambridge. However, after the 1949 election, the new government led by Robert Menzies was less supportive of the university. In 1959, the ANU was combined with another college, which meant it would also teach undergraduate students, not just focus on research. Despite these challenges, the ANU remained a university where research was very important.

In 1951, Oliphant applied for a visa to visit the United States for a science conference, but it was delayed. This was during a time called the Red Scare in the US, where there was a fear of communism. He was later refused permission to travel through the US in 1954. Because of this, the Australian government also limited his access to secret nuclear information.

In 1955, Oliphant started the design and building of a 500 megajoule homopolar generator (HPG), the largest in the world. This huge machine had three discs, each 3.5 metres (11 ft) wide and weighing 38 tonnes (37 long tons). It was finished in 1963 and was used to power experiments in plasma physics. It was stopped in 1985.

Oliphant helped found the Australian Academy of Science in 1954 and was its president until 1956. He raised money to build a special building for the Academy, which became one of Canberra's most unique buildings.

Oliphant retired as a professor in 1967. He was then invited by the Premier of South Australia, Don Dunstan, to become the Governor of South Australia. He served from 1971 to 1976. He also helped establish the Australian Democrats political party in 1977.

Oliphant was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) in 1959. In 1977, he was appointed a Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) for his great achievements in public service.

Death

Mark Oliphant passed away in Canberra on July 14, 2000, at the age of 98.

Legacy

Many places and things are named after Mark Oliphant to honor him. These include the Oliphant Building at the Australian National University, the Mark Oliphant Conservation Park, a science competition for high school students in South Australia, a wing of the Physics Building at the University of Adelaide, a school in Adelaide called Mark Oliphant College, and a bridge in Canberra.

His scientific papers are kept in libraries at the Australian Academy of Science and the University of Adelaide. Mark Oliphant's nephew, Pat Oliphant, is a famous cartoonist who won a Pulitzer Prize. His daughter-in-law, Monica Oliphant, is also a distinguished Australian physicist who works on renewable energy.

Honours and awards

- 1937 Elected Fellow of the Royal Society

- 1943 Awarded Hughes Medal by the Royal Society

- 1946 Awarded Silvanius Thomson Medal, Institute of Radiology

- 1948 Awarded Faraday Medal by the Institution of Engineers

- 1954 Elected (Foundation) Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science

- 1954 Elected (Foundation) President of the Australian Academy of Science

- 1955 Invited to deliver the Bakerian Lecture by the Royal Society

- 1955 Invited to deliver the Rutherford Memorial Lecture by the Royal Society

- 1956 Awarded Galathea Medal by King Frederick IX of Denmark

- 1959 Created Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- 1961 Awarded Matthew Flinders Medal and Lecture

- 1976 Inducted as first Honorary Fellow and a Foundation Fellow of the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering

- 1977 Appointed Companion of the Order of Australia

- Memorials to Mark Oliphant

-

Plaque on the Jubilee 150 Walkway

See also

In Spanish: Mark Oliphant para niños

In Spanish: Mark Oliphant para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |