Don Dunstan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Don Dunstan

|

|

|---|---|

Dunstan in 1968

|

|

| 35th Premier of South Australia Elections: 1968, 1970, 1973, 1975, 1977 |

|

| In office 2 June 1970 – 15 February 1979 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governor |

|

| Deputy | Des Corcoran |

| Preceded by | Steele Hall |

| Succeeded by | Des Corcoran |

| In office 1 June 1967 – 17 April 1968 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governor | Sir Edric Bastyan |

| Deputy | Des Corcoran |

| Preceded by | Frank Walsh |

| Succeeded by | Steele Hall |

| Leader of the Opposition in South Australia | |

| In office 17 April 1968 – 2 June 1970 |

|

| Deputy | Des Corcoran |

| Preceded by | Steele Hall |

| Succeeded by | Steele Hall |

| Leader of the South Australian Labor Party | |

| In office 1 June 1967 – 15 February 1979 |

|

| Preceded by | Frank Walsh |

| Succeeded by | Des Corcoran |

| Treasurer of South Australia | |

| In office 2 June 1970 – 15 February 1975 |

|

| Premier | Don Dunstan |

| Preceded by | Steele Hall |

| Succeeded by | Des Corcoran |

| In office 1 June 1967 – 16 April 1968 |

|

| Premier | Don Dunstan |

| Preceded by | Frank Walsh |

| Succeeded by | Steele Hall |

| 38th Attorney-General of South Australia | |

| In office 20 June 1975 – 9 October 1975 |

|

| Premier | Don Dunstan |

| Preceded by | Len King |

| Succeeded by | Peter Duncan |

| In office 10 March 1965 – 16 April 1968 |

|

| Premier | Frank Walsh |

| Preceded by | Colin Rowe |

| Succeeded by | Robin Millhouse |

| Member of the South Australian Parliament for Norwood |

|

| In office 7 March 1953 – 10 March 1979 |

|

| Preceded by | Roy Moir |

| Succeeded by | Greg Crafter |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 21 September 1926 Suva, Colony of Fiji |

| Died | 6 February 1999 (aged 72) Norwood, South Australia |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Political party | Labor |

| Spouses |

Gretel Elsasser

(m. 1949; div. 1974)Adele Koh

(m. 1976; died 1978) |

| Domestic partners | Stephen Cheng (1986–1999) |

| Children | 3 |

Donald Allan Dunstan (21 September 1926 – 6 February 1999) was an Australian politician. He served as the 35th Premier of South Australia from 1967 to 1968, and again from 1970 to 1979. He was a member of the House of Assembly for the area of Norwood from 1953 to 1979. Dunstan also led the Labor Party in South Australia from 1967 to 1979. Before becoming premier, he was the Attorney-General (chief legal advisor) and Treasurer of South Australia (in charge of state money). He is the fourth longest-serving premier in South Australian history.

In the late 1950s, Dunstan became known for fighting against the death penalty. While his party was not in power, he helped bring about changes for Aboriginal rights. He also helped the Labor Party stop supporting the White Australia policy, which limited non-European immigration. Dunstan became Attorney-General after the 1965 election. He then took over from Frank Walsh as premier in 1967.

Even though his party had more votes, Labor lost two seats in the 1968 election. The Liberal and Country League (LCL) formed the government with help from an independent politician. Dunstan then strongly criticised the "Playmander", an unfair voting system. He convinced the LCL to make the voting system fairer. After these changes, Labor won 27 out of 47 seats in the 1970 election. They also won elections in 1973, 1975, and 1977.

Dunstan's government made many modern changes. They recognised Aboriginal land rights. They also appointed the first female judge, Dame Roma Mitchell, and the first non-British governor, Sir Mark Oliphant. Later, the first Indigenous governor, Sir Douglas Nicholls, was appointed. His government also created laws to protect consumers, improved public education and health, and ended the death penalty. They relaxed censorship and drinking laws. Dunstan also created a ministry for the environment and introduced anti-discrimination law. He made voting fairer by lowering the voting age to 18 and giving everyone the right to vote. He also completely removed the unfair voting system. Dunstan helped create Rundle Mall, protected historic buildings, and supported arts by backing the Adelaide Festival Centre and the South Australian Film Corporation.

However, there were also challenges. The economy started to slow down. A plan to build a new city called Monarto was stopped when the economy and population growth stalled. This happened after a lot of money had already been spent. After winning four elections in a row, Dunstan's government faced problems in 1978. This was after he removed Police Commissioner Harold Salisbury, which caused a debate about whether he had interfered with an investigation. Economic problems and unemployment also grew. Dunstan resigned from being premier and from politics in 1979 due to health issues. He lived for another 20 years, continuing to speak out for modern social policies.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Dunstan was born on 21 September 1926 in Suva, Colony of Fiji. His parents, Francis and Ida Dunstan, were Australians of Cornish background. They had moved to Fiji in 1916 because his father managed the Adelaide Steamship Company. Don spent his first seven years in Fiji and started school there. He was often sick, so his parents sent him to South Australia, hoping the drier weather would help him get better. He lived in Murray Bridge for three years with his mother's parents. While in Fiji, Dunstan easily mixed with Indian settlers and local people. This was not common among many white people on the islands at the time.

He won a scholarship to study classical studies at St Peter's College. This was a private school for the sons of wealthy families in Adelaide. He became good at public speaking and acting, winning the school's public speaking prize twice. In 1943, he played the main character in a play called Abraham Lincoln. The school magazine said he was the "chief contributor to the success of the occasion". He was strong in classical history and languages but disliked mathematics. He was known for being a bit rebellious. Dunstan finished school in 1943, ranking in the top 30 in the state exams.

When he was young, Dunstan supported the conservative Liberal and Country League (LCL) party. His uncle, Sir Jonathan Robert Cain, who was a former Lord Mayor of Adelaide, influenced him. Dunstan even handed out voting cards for the LCL in state elections. He later said he was a "refugee" from the traditional Adelaide establishment.

His political views changed during his university years. He studied law and arts at the University of Adelaide. He became very active, joining the University Socialist Club, the Fabian Society, and the Student Representative Council. After a short time with the Communist Party, he joined the Australian Labor Party.

Dunstan was different from most Labor Party members at the time. He had an upper-class accent, which some working-class Labor members made fun of. He paid for his education by working in theatre and radio. He earned two degrees, with majors in Latin, history, and politics. He came first in political science.

After graduating, Dunstan moved to Fiji with his wife, Gretel. He became a lawyer there. They returned to Adelaide in 1951 and lived in Norwood. They took in boarders to earn extra money.

Starting in Politics

Dunstan became the Labor candidate for the electoral district of Norwood in the 1953 election. His campaign was colourful. Posters of his face were put on every power pole in the area. Labor supporters walked the streets to promote him. He especially targeted the large Italian immigrant population. He gave out translated copies of a statement the sitting LCL member, Roy Moir, had made about immigrants. Moir had said that "these immigrants are of no use to us... most of them have no skills at all." Dunstan won the seat and became a member of the South Australian House of Assembly.

Dunstan became the strongest critic of the LCL Government led by Sir Thomas Playford. He strongly criticised the unfair voting system, known as the "Playmander". This system gave more voting power to rural areas, where the LCL had strong support. Votes in rural areas could be worth ten times more than votes in city areas. For example, in the 1968 election, a rural seat had 4,500 votes, while a city seat had 42,000 votes. Dunstan brought a new, more direct style to South Australian politics. He was not afraid to challenge the government strongly. Most of his Labor colleagues had become used to the LCL's power and tried to work with them.

In 1954, the LCL introduced a bill to make the rural voting advantage even stronger. Dunstan called this bill "immoral". His strong language led to him being removed from the parliament chambers. He was the first politician to be expelled in years and made newspaper headlines. However, he did not gain much public attention at first. The main newspaper, The Advertiser, had a policy of ignoring his activities.

Rise to Power

At the national level, Dunstan worked with fellow Labor member Gough Whitlam to remove the White Australia policy from the Labor Party's platform. This policy limited non-European immigration. Older Labor members, especially from trade unions, strongly opposed changing it. But the "New Guard" of the party, including Dunstan, wanted to end it. After several attempts, the policy was removed from Labor's platform in 1965. Dunstan took credit for this change. Whitlam later fully ended the White Australia policy in 1973 when he became Prime Minister of Australia.

Dunstan also pushed for similar changes for Indigenous Australians. In 1962, a bill was introduced to loosen rules that had limited Indigenous Australians' rights and led to segregation. The first plan still had some restrictions, especially for full-blooded Aboriginal people. Dunstan was a key voice in Labor's opposition to these double standards. He called for all race-based restrictions to be removed. He succeeded in getting changes to loosen controls on property and the rules that confined Indigenous Australians to Aboriginal reserves. However, his attempts to remove different rules for people of mixed and full Aboriginal heritage failed. His idea to have at least half of the Aboriginal Affairs Board members be Indigenous Australians also failed. Even with the bill passed, some restrictions remained. Dunstan questioned the policy of assimilation, which he felt diluted Indigenous cultures.

Labor won the 1965 election, forming a government for the first time in 32 years. Frank Walsh became Premier of South Australia. Even though Labor won 55 percent of the votes, the "Playmander" system meant they only won 21 out of 39 seats, a small majority. Dunstan became Attorney-General and Minister of Community Welfare and Aboriginal Affairs. He was the youngest minister in the cabinet. Dunstan had a big impact on government policy as Attorney-General. He was the clear choice to replace the 67-year-old Walsh, who was set to retire in 1967.

The Walsh Government made many important changes. They updated and relaxed laws about alcohol, gambling, and entertainment. Social welfare was slowly expanded, and Aboriginal reserves were created. Strict rules on Aboriginal access to alcohol were lifted. Women were granted "equal pay for work of equal value," and laws against racial discrimination were passed. Town planning became law, and a State Planning Authority was created. Workers gained more rights, and the education department became more flexible. Many of these changes were not radical; they mostly filled gaps left by the previous LCL government. However, Labor was consistently outnumbered in the Legislative Council, the upper house, so some desired laws did not pass.

An economic downturn began in South Australia after Labor took office in 1965. Unemployment rose from the lowest in the country to the second highest, and immigration dropped. The Liberals blamed Labor for this, calling it the "Dunstan Depression."

In the 1966 Australian federal election, Labor lost a lot of support in South Australia. The Liberals replaced Playford with the younger, more modern Steele Hall. Facing a difficult situation, Labor changed leaders in May 1967. Walsh stepped down, and Dunstan won the leadership over Des Corcoran.

Dunstan's first time as Premier was busy, with many reforms and efforts to end the economic downturn. By late 1967, the economy started to recover slightly. The 1967–68 budget had a deficit, with money spent to boost the economy. Dunstan criticised the national government for not helping South Australia's economy enough.

Elections: 1968–1970

For the 1968 election, Labor focused its campaign on Dunstan. Voters liked him; surveys showed 84% of people in city areas approved of him. In a campaign focused on the leaders, Hall and Dunstan travelled the state. The main issues were the leaders, the unfair voting system, and the economy. Television was used a lot for the first time in this election, and Dunstan, a good speaker, used it well. Even though Labor won 52% of the main votes, they lost two seats. This resulted in a hung parliament, with the LCL and Labor each having 19 seats. The independent politician, Tom Stott, held the deciding vote. Stott, a conservative, agreed to support the LCL.

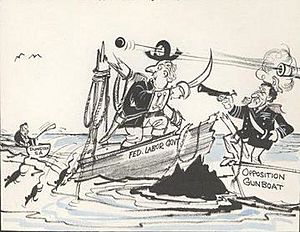

There was talk that Dunstan would call a new election, but he knew it would not help. Instead, he wanted to force the LCL to end the unfair voting system. Even though Stott's decision meant Dunstan could not stay premier, Dunstan did not resign right away. He used the six weeks before the new parliament met to highlight the unfair voting system. Protests were held on 15 March, where Dunstan spoke to over ten thousand people. He said, "We need to show that the people of SA feel that at last the watershed has been reached... they will not continue to put up with a system which is as undemocratic as the present one." On 16 April, Dunstan lost a vote of confidence. He then resigned, and Hall became premier. However, the six weeks of protests brought national attention to the unfair voting system. This put more pressure on the LCL to agree to reforms. This period is seen as a very important political event.

After Playford left, the LCL brought in younger, more modern members. Hall's government continued many social reforms started by the Walsh/Dunstan governments. The LCL started to split into different groups. South Australia's economy began to improve under Hall, with full employment returning. While in opposition, Des Corcoran became Dunstan's deputy, and they worked well together.

Hall was embarrassed that the LCL could form a government despite losing the popular vote. He was committed to a fairer voting system. Soon after taking office, he completely changed the electoral system. The lower house was expanded from 39 to 47 seats, with more seats in Adelaide. While rural areas still had a slight advantage, Adelaide now elected a majority of the parliament. This made a Labor win in the next election likely. It was widely believed that Hall knew he was effectively handing the premiership to Dunstan by reforming the voting system.

Stott withdrew his support in 1970 over a dispute about the Chowilla Dam. South Australia then went to an election. The dam issue was not a major election topic. Attempts by the Democratic Labor Party to label Dunstan as a communist had little effect. The LCL campaigned heavily on Hall, while Dunstan promised big social changes and more community services. He said, "We'll set a new standard of social advancement that the whole of Australia will envy." Dunstan won the 1970 South Australian state election easily, taking 27 seats to the LCL's 20. The fairer voting system meant that Labor won more seats even with a similar share of votes as in 1968. Political experts said, "A Dunstan decade seems assured."

The Dunstan Decade

Dunstan quickly organised his new team of ministers. He served as his own Treasurer and took on several other roles. Deputy Premier Des Corcoran handled most of the infrastructure roles, like Marine and Harbours. Corcoran helped manage relationships with other Labor politicians. Bert Shard became Health Minister, overseeing new public hospitals. Hugh Hudson took on Education, a key role for a government wanting to change the education system. Geoff Virgo, the new Transport Minister, dealt with transport plans for Adelaide. Len King became Attorney-General and Aboriginal Affairs Minister, even though he was new to parliament. Dunstan built a strong group of loyal ministers around him, a very different style from past premiers.

Soon after the election, Dunstan went to Canberra for the annual Premiers' Conference. He was the only Labor premier there. His government wanted to greatly increase funding in key areas and sought more money from the national government. This led to disagreements with Prime Minister John Gorton. National funding to South Australia was not increased. Dunstan appealed to the Federal Grants Commission and received more money than he expected. This money, along with funds from other sources, was used for health, education, and arts programs.

When Governor Sir James Harrison died in 1971, Dunstan had the chance to choose a new governor. He nominated Sir Mark Oliphant, a physicist who had worked on the Manhattan Project. Dunstan wanted an active and notable South Australian to take on the role, rather than British ex-servicemen. Sir Mark Oliphant was sworn in without problems. Although the governor's role is mostly ceremonial, Oliphant brought energy to it. He used his position to speak out against environmental damage. Oliphant's time as governor was successful, though he sometimes disagreed with Dunstan.

In 1972, major plans for the state's population growth began. Adelaide's population was expected to reach 1.3 million. The Dunstan Government rejected earlier transport and water plans. Instead, they planned to build a new city called Monarto, 83 kilometres from Adelaide. Dunstan did not want Adelaide's suburbs to spread too much. He argued that Monarto would be close to Adelaide by freeway and have enough water. The government hoped to prevent Adelaide from sprawling into the Mount Lofty Ranges. Critics called the project "Dunstan's Versailles in the bush." Environmental groups worried about Monarto's effect on the River Murray. Later, it was found that hard rock under the ground would cause drainage problems.

From 1970 to 1973, many laws were passed in South Australia. Workers received more welfare benefits. Drinking laws were further relaxed. An Ombudsman (a public official who investigates complaints) was created. Censorship was loosened, and seat belts became mandatory. The education system was updated, and the public service grew. Adelaide's water supply was fluoridated in 1971, and the age of adulthood was lowered from 21 to 18. A Commissioner of Consumer Affairs was created. A demerit point system was introduced for bad driving to reduce road accidents. Workers' compensation was improved. Police powers were limited after a protest against the Vietnam War was broken up by police. A special investigation was held into the police commissioner's actions, leading to laws giving the government more control over the police. The dress code for the Parliament was relaxed. Dunstan himself caused a stir in 1972 by wearing pink shorts to Parliament House. This image remains famous.

Dunstan strongly promoted multiculturalism. He was known for attending Cornish, Italian, and Greek Australian cultural festivals. He also appreciated Asian art and wanted to build trade links with Asia. His involvement in these cultural exchanges helped Labor gain strong support from immigrant communities. Dunstan later recalled, "When I proposed the establishment of a Cornish Festival... people of Cornish descent came flocking."

Dunstan had criticised past governments for destroying historic buildings. He worked to protect them from being replaced by new high-rise buildings. In 1972, the government bought Edmund Wright House to save it. In 1975, the Customs House at Semaphore was saved from demolition. He also helped save Ayers House by having it turned into a restaurant. However, some controversial developments also happened. Parts of Hallett Cove and vineyards in several suburbs were developed for housing. This drew criticism, as Dunstan also promoted South Australian wine.

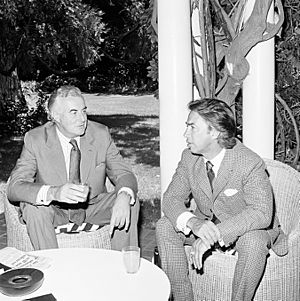

To build economic ties with South-East Asia, Dunstan met leaders from the Malaysian state of Penang in 1973. He connected with Chong Eu Lim, the Chief Minister of Penang. Dunstan then organised cultural and economic exchanges between the two states. "Penang Week" was held in Adelaide, and "South Australia Week" was held in Penang. In the same year, the Adelaide Festival Centre opened. It was Australia's first multi-purpose performing arts complex.

Over six years, government funding for the arts increased sevenfold. In 1978, the South Australian Film Corporation began its work. During Dunstan's time, famous films like Breaker Morant, Picnic at Hanging Rock, and Storm Boy were made in South Australia. Commentators said Dunstan's support for the arts and fine dining attracted artists and writers to the state, changing its atmosphere.

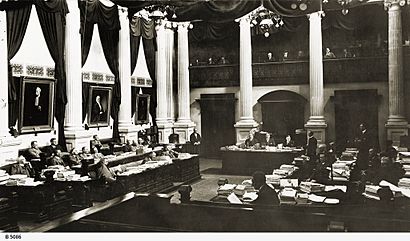

The Legislative Council, the upper house of Parliament, was mostly non-Labor. This was because only voters who met certain property and wealth rules could vote for its members. This, combined with the remaining "Playmander" unfairness, made it hard for Labor to get the representation it wanted. The Legislative Council often weakened or rejected Labor laws. Bills to legalise homosexuality, abolish corporal (physical) and capital punishment (death penalty), and allow gambling were rejected. A public vote showed support for Friday night shopping, but Labor's law was blocked by the LCL in the upper house.

Dunstan called an election for March 1973, hoping to gain support for changes to the Legislative Council. The LCL was very divided. The more liberal part of the party, led by Hall, wanted to introduce universal voting rights for the upper house, like Dunstan. But the more conservative members did not. The conservatives then limited Hall's powers, causing him to resign and form a new group called the Liberal Movement (LM). Labor took advantage of these divisions and won easily. They campaigned with the slogan "South Australia's Doing Well with Labor." Labor won 51.5% of the main votes and secured a second majority government with 26 seats. This was only the second time a Labor government in South Australia had been re-elected for a second term. They also gained two more seats in the Legislative Council, giving them six out of twenty members. Labor gained momentum when the LCL removed LM members from its ranks, forcing them to either leave the LM or leave the LCL and join the LM as a separate party.

Dunstan saw reforming the Legislative Council as an important goal and a major achievement of his government. Labor wanted to abolish the Legislative Council, but Dunstan knew this was not possible during his term. Instead, he worked to reform it. Two bills were prepared for Legislative Council reform. One was to lower the voting age to 18 and introduce universal suffrage (everyone having the right to vote). The other was to have councillors elected from a single statewide area using a system of proportional representation (where parties get seats in proportion to their votes). The LCL initially blocked both bills. They said they would only accept them if changes were made to the second one. Dunstan's government agreed to some changes, and the legislation passed.

During his second term, Dunstan started efforts to build a petrochemical complex at Redcliff, near Port Augusta. Negotiations were held with several large companies, but nothing happened. Laws were passed to create a Land Commission and control urban land prices. However, a bill to create "a right to privacy" was defeated after protests from journalists. A law to require refunds for returning beverage containers to promote recycling also failed.

Before the 1975 national and state elections, Australia faced economic problems. The 1973 oil crisis greatly increased living costs. Local industries struggled, and government funds were low. In response, Dunstan's government sold railways that were losing money to the national government and introduced new taxes to allow wage increases. These changes had unexpected results: inflation increased, and workers were still unhappy with wages. The LCL, now called the Liberal Party, had reorganised and become more appealing. Dunstan called an early election and blamed the national government for South Australia's problems. In a TV speech before the election, he said, "My Government is being smeared and it hurts. They want you to think we are to blame for Canberra's mistakes. The vote on Saturday is not for Canberra, not for Australia, but for South Australia."

Labor remained the largest party in Parliament, but lost the two-party preferred vote and saw its number of seats decrease from 26 to 23. The Liberals held 20 seats, the Liberal Movement two, the Country Party one, and an independent held the last seat. Dunstan appealed to the independent and offered him the role of Speaker. However, the reforms to the Legislative Council's election worked well. Of the 11 seats up for election, Labor won six, and the LM won two. This gave Labor a total of 10 seats in the upper house. With the help of the LM, they could now pass reforms that the Liberals opposed.

Dunstan continued to push for more laws. He wanted to expand on the Hall Government's electoral boundary reforms to make voting districts more equal in size. The law aimed to create 47 voting districts with roughly equal numbers of voters. An independent commission would oversee these changes. The bill passed with the support of the breakaway LM in the upper house.

One famous example of Dunstan's style and media skill happened in January 1976. A psychic predicted that God would destroy Adelaide with a tsunami due to Dunstan and the state's social changes. This was widely reported, causing some residents to sell their homes and leave. Dunstan promised to stand on the seashore at Glenelg and wait for the predicted disaster. He did so on 20 January, and nothing happened. He made headlines in the United Kingdom for his defiance.

In 1976, the Dunstan Government increased its law-making efforts. The bill to abolish the capital punishment passed easily. Laws reforming homosexuality eventually passed in September. Shopping hours, which used to be very strict, became the most open in the nation. Friday night shopping was introduced for the city, and Thursday night shopping for the suburbs. The law requiring deposits on beverage containers was finally passed. The first signs of Monarto's failure began to appear. Birth rates dropped, immigration slowed, and the economy was stagnant. South Australia's strong population growth stopped. However, state money continued to be poured into the Monarto project. By the time Monarto was stopped after Dunstan left office, over $20 million had been spent. This failed project is often seen as Dunstan's biggest failure. Also, the national government removed funding for shipbuilding at Whyalla, forcing operations to be reduced.

After Oliphant's term ended, Dunstan appointed the first Indigenous Australian Governor, Sir Douglas Nicholls, a former football player and clergyman. After Nicholls resigned due to health issues in 1977, a second clergyman, Methodist Keith Seaman, took the post. However, this appointment was not successful. Seaman became involved in an unspecified issue and admitted to a "grave impropriety." He did not resign but kept a low profile. Dunstan also appointed Dame Roma Mitchell as Australia's first female Supreme Court judge.

Dunstan broke new ground in Australian politics with his policies on native title for Aboriginal people. The North West Aboriginal Reserve (NWAR) covered over 7% of the state's land and was home to the Pitjantjatjara people. In 1977, a tribal group asked for the lands to be given to the traditional owners. Dunstan agreed to an investigation and then introduced the Pitjantjatjara Land Rights Bill. This bill proposed that a tribal body, the Anangu Pitjantjatjaraku, would control the NWAR and other lands. It also proposed allowing this body to decide on mining proposals and receive royalties. This caused concern among mining companies. However, a committee of politicians from both parties supported the bill. Labor lost power before the bill passed. The new Liberal government initially said they would remove the mining restrictions, but large public protests forced them to change their minds. A bill similar to Dunstan's was passed. This legislation, largely started by Dunstan, was the most progressive in Australia. In the 1980s, over 20% of the land was returned to its traditional owners.

Dunstan called another quick election in September for the 1977 election. He hoped to recover from the previous election, which had been affected by the removal of the national Labor Government. With the unfair "Playmander" system gone, conditions were better for Labor. The campaign went smoothly and used the unpopularity of the national Liberal government. Labor won a clear majority with 51.6% of the main votes and 27 seats.

Departure from Office

Since 1949, there had been a "Special Branch" within the South Australian Police. This branch collected information on thousands of people and organisations. Dunstan and his government were concerned about this, especially because the branch seemed to have a political bias. It held files on Labor politicians, communists, church leaders, and trade unionists. It also had "pink files" on gay community activists from before homosexuality was legalised. While only two Labor politicians did not have files, the branch had far fewer files on Liberal Party figures. Dunstan had known about the branch since 1970 but said the police commissioner had assured him the files were not focused on left-wing political figures.

However, Peter Ward, a journalist, published a story about the files. An investigation was conducted by Justice White of the Supreme Court of South Australia. His report, given to Dunstan on 21 December 1977, stated that the files were "scandalously inaccurate, irrelevant to security purposes and outrageously unfair to hundreds, perhaps thousands, of loyal and worthy citizens." The report also noted that the files mostly focused on left-wing politicians and activists, and that Dunstan had been misled by Police Commissioner Harold Salisbury. After reviewing the findings, Dunstan removed Salisbury from his position in January and threatened to make the report public.

However, a debate started about the inquiry and Dunstan's actions. Salisbury had a reputation for integrity. A Royal Commission (a major public inquiry) investigated the matter. It cleared Dunstan's government of any wrongdoing and found that it had not known about the Special Branch's activities earlier. Dunstan had removed Salisbury for misleading Parliament about the "pink files." Many of the Special Branch files were burned. Salisbury retired to the United Kingdom.

Initially, there were no other major issues for Dunstan. However, the economy remained weak. Financial difficulties forced a freeze on public sector growth and hospital developments. There were also claims of theft and mismanagement in the health system. But the Liberal opposition was disorganised and unpopular, so they could not effectively pressure Dunstan.

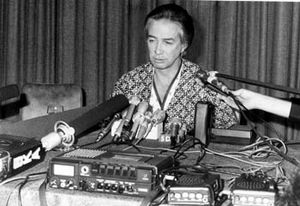

Towards the end of the year, politicians and the media started to scrutinise Dunstan more closely. He became uncomfortable dealing with the press. He angrily denied claims that he was using government money to build a lavish home in Malaysia. He held a press conference to denounce rumours and claimed that "reactionary forces" and "right-wing journalists" were trying to harm his government.

Dunstan also faced difficulties with policy. Divisions began to appear in the Labor Party. The discovery of uranium deposits near Roxby Downs created a problem for the premier. Mining the uranium promised a valuable economic boost, but the government had a ban on its mining for safety reasons. Dunstan was against uranium mining but was seen as not strong enough by environmentalists. He was also criticised by business leaders. By May, his approval rating had fallen, and unemployment was rising.

Dunstan became very ill. When Parliament resumed, he collapsed and had to use a walking stick. His doctor advised him to rest for six months. The Liberal Opposition criticised the Labor Party, saying it was "as ailing as the man who led it." In a televised press conference on 15 February 1979, Dunstan announced his retirement as premier from his hospital room. He was visibly shaking and wearing a dressing gown.

Political expert Andrew Parkin said one of Dunstan's main achievements was showing that state governments could make big changes with major impacts. He pointed to Dunstan's wide-ranging social reforms, and how many other state governments later followed South Australia's lead.

Life After Politics

After Dunstan resigned from Parliament, his deputy Des Corcoran became party leader and Premier. In the election that followed, Labor lost power. The Tonkin Liberal Government took over and officially stopped the Monarto project. Dunstan travelled to Europe after leaving the hospital, staying in Perugia for five months to study Italian. He then returned to Adelaide and lived quietly for three years, not finding work that interested him.

During this time, he became less interested in South Australian politics. A book by two Adelaide journalists was released, making allegations about Dunstan's private life. Dunstan dismissed the book as "a farrago of lies" in his 1981 memoirs, titled Felicia.

From May 1980 to early 1981, he worked as editor for POL. In 1982, he moved to Victoria and was appointed the Director of Tourism. This caused an outcry in South Australia due to the two states' rivalry. Dunstan said he had wanted a role in shaping his home state's future but had been ignored for three years. He felt that public figures in South Australia thought his high profile might overshadow them. Dunstan stayed in the Director of Tourism role until 1986. He returned to Adelaide after disagreements with the Victorian government.

He was the national president of the Freedom from Hunger Campaign (1982–87). He also led the Movement for Democracy in Fiji (from 1987) and was national chairman of Community Aid Abroad (1992–93). Dunstan was a professor at the University of Adelaide from 1997 to 1999. He also played himself in the 1989 Australian film Against the Innocent.

In his retirement, Dunstan continued to strongly criticise economic rationalism (a focus on free markets) and privatisation (selling government-owned services to private companies). He often wrote about the dangers of racism. A year before his death, the unwell Dunstan spoke out against Labor's economic policies. Despite his achievements, Dunstan was largely overlooked for official honours after leaving office. The Dunstan Playhouse was later named to honour his contribution to the performing arts.

Personal Life

While living in Norwood and studying at university, Dunstan met his first wife, Gretel Elsasser. Her Jewish family had fled Nazi Germany to Australia. They married in 1949 and moved to Fiji. They returned to Adelaide in 1951 and settled in Norwood with their young daughter, Bronwen. The family lived simply for several years while Dunstan started his law practice. They took in boarders to earn extra income. Gretel later gave birth to two sons, Andrew and Paul.

In 1972, Dunstan separated from his wife and moved into a small apartment in Kent Town. The family home was sold as two of the children were already at university. In 1974, the couple divorced. Dunstan described this period as "very bleak and lonely" at first. He made new friends, and cooking became his hobby. In 1974, Dunstan bought another house, partly funded by a cookbook he was writing. In 1976, Don Dunstan's Cookbook was published. It was the first cookbook released by a serving Australian leader. More generally, Dunstan encouraged a revolution in fine dining in the state. Many new restaurants opened, and the variety of food increased. He also promoted the viticulture (wine-making) industry.

In 1973, Adele Koh, a Malaysian journalist, began working for Dunstan. She had been expelled by the Singaporean Government for criticising its policies. The two began a relationship in 1974 and married in 1976. Adele was diagnosed with advanced lung cancer in May 1978 and died in October. Her death deeply affected Dunstan, and his own health began to suffer.

In 1986, Dunstan met Stephen Cheng, a science student. Together, they opened a restaurant called "Don's Table" in 1994. Dunstan lived with Cheng in their Norwood home for the rest of his life. Cheng cared for Dunstan through his illness.

Death

In 1993, Dunstan was diagnosed with an aggressive throat cancer and later an inoperable lung cancer. He died on 6 February 1999. Dunstan was not a smoker but had been exposed to passive smoking for a long time. A public memorial service was held on 9 February at the Adelaide Festival Centre to honour his love of the arts. Many important figures attended, including former Prime Ministers Gough Whitlam and Bob Hawke. Thousands more gathered outside the centre. State flags were flown at half-mast, and the service was televised live.

Legacy

A theatre in the Festival Centre was renamed the Dunstan Playhouse.

In 2012, the voting district of Norwood was renamed Dunstan for the 2014 election. In 2014, a biography titled Don Dunstan Intimacy & Liberty by Dino Hodge was published.

In 1988, Dunstan donated a collection of his political, professional, and personal files, photographs, speeches, and other items to Flinders University Library. These can be viewed for research.

Don Dunstan Foundation

The Don Dunstan Foundation was started by Dunstan at the University of Adelaide in 1999, shortly before his death. It aims to promote progressive change and honour Dunstan's memory. Dunstan spent his last months helping to set up the foundation. At its launch, Dunstan said, "What we need is a concentration on the kind of agenda which I followed and I hope that my death will be useful in this."

The Foundation works to represent and advocate for Dunstan's values, such as cultural diversity, fair distribution of wealth, human rights, and Indigenous rights in Australia. It holds annual events, including a conference on homelessness and various lectures.

Don Dunstan Award

Since 2003, the Adelaide Film Festival has given out The Don Dunstan Award. This award recognises individuals who have made an outstanding contribution to the Australian film industry. Recipients are chosen for enriching Australian screen culture through their work. Past winners include David Gulpilil and Scott Hicks. In 2013, after receiving the award, Hicks said that Dunstan's vision for creating a film industry in South Australia was key to his own career development.

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |