William Sterling Parsons facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Sterling Parsons

|

|

|---|---|

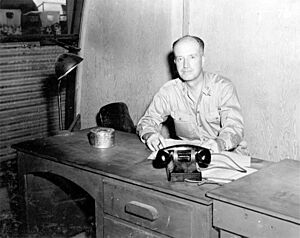

Parsons c. 1946–1953

|

|

| Nickname(s) | Deak |

| Born | 26 November 1901 Chicago, Illinois, US |

| Died | 5 December 1953 (aged 52) Bethesda, Maryland, US |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ |

United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1922–1953 |

| Rank | Rear admiral (upper half) |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

|

| Alma mater | United States Naval Academy (BS) |

William Sterling Parsons (born November 26, 1901 – died December 5, 1953) was an American naval officer. He was an expert in ordnance, which is the study of weapons and ammunition. During World War II, he worked on the top-secret Manhattan Project. This project created the first atomic bombs.

Parsons is most famous for being the "weaponeer" on the Enola Gay aircraft. This plane dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945. To make sure the bomb wouldn't accidentally explode if the plane crashed during takeoff, Parsons decided to arm it while the plane was flying. He climbed into the bomb bay and carefully put the parts together. He received the Silver Star medal for his important role in this mission.

Parsons graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1922. He served on many warships, including the battleship USS Idaho. He became very skilled in ordnance and studied how projectiles fly (called ballistics).

He was one of the first people to see how useful radar could be. Radar uses radio waves to find ships and planes. In 1940, Parsons helped develop the proximity fuze. This was a special fuse that could make a shell explode when it got close to its target, without needing a direct hit. This invention was very important for shooting down enemy aircraft.

In 1943, Parsons joined the Manhattan Project. He was in charge of designing and testing the non-nuclear parts of the atomic bombs. He also led the program to deliver the bombs by plane. After the war, he became a rear admiral. He helped with nuclear weapon tests and worked on developing a nuclear-powered navy.

Contents

Early Life and Education

William Sterling Parsons was born in Chicago, Illinois, on November 26, 1901. He was the oldest of three children. When he was eight, his family moved to Fort Sumner, New Mexico. There, he learned to speak Spanish very well.

He went to high school in Santa Rosa and Fort Sumner, New Mexico. In 1917, he took the entrance exam for the United States Naval Academy. Even though he was only 16 and younger than most students, he passed and was accepted. He started at Annapolis, Maryland, in 1918 and graduated in 1922. At the Naval Academy, he got the nickname "Deak," which stuck with him.

After graduating in 1922, Parsons became an ensign. He was put in charge of a large gun on the battleship USS Idaho. In 1927, he went back to Annapolis to study ordnance. He became very knowledgeable about weapons and how they work.

In 1933, Parsons started working with the United States Naval Research Laboratory. Here, he learned about early experiments with radar. He quickly realized that radar could be used to find ships and aircraft, and even track shells. He pushed for more research into this new technology, even when others thought it wasn't important.

Parsons married Martha Cluverius in 1929. They had three daughters. In 1936, he became an executive officer on the destroyer USS Aylwin. He was promoted to lieutenant commander in 1937. He was known for being very dedicated to his naval duties.

The Proximity Fuze

In 1939, Parsons returned to Dahlgren, Virginia, to work on experiments. By this time, World War II had started, and there was a greater need for new weapons. In 1940, Parsons and scientist Merle Tuve began working on a new idea: the proximity fuze.

Shooting down an airplane with an anti-aircraft gun was very hard. Gunners used time fuzes to make shells explode at a certain time, hoping to hit the plane. Parsons and Tuve wanted to use radar to make a shell explode when it got close to an enemy aircraft. This would greatly increase the chances of hitting it.

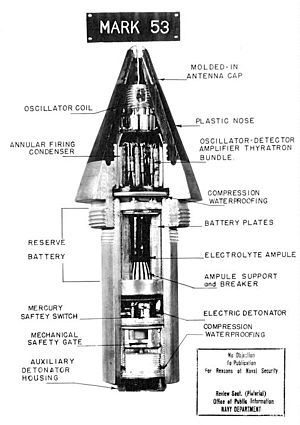

Making a radar small enough to fit inside a shell was a huge challenge. The tiny vacuum tubes inside had to survive the force of being fired from a gun and spinning very fast. But they succeeded! In 1942, the first proximity fuzes were tested and worked.

Parsons personally took these new fuzes, called VT (variable time) fuze, Mark 32, to the South Pacific. On January 6, 1943, he was on the cruiser USS Helena. During a battle, Helena fired a shell with a VT fuze at an enemy plane. The shell exploded near the plane, and it crashed. This was the first time an enemy aircraft was shot down with a VT fuze.

At first, these fuzes were only used over water to keep them secret. Later, they were used over land and were very effective against German V-1 flying bombs and ground targets. By the end of 1944, 40,000 VT fuzes were being made every day.

The Manhattan Project

Developing the Atomic Bomb

In June 1943, Parsons joined the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, New Mexico. This was a top-secret project to build the atomic bomb. He became the Associate Director under J. Robert Oppenheimer. Parsons was responsible for all the non-nuclear parts of the bombs, including their design and testing.

Parsons and his family moved to Los Alamos. He helped set up the local school for the children of the scientists and workers. He also brought many skilled naval officers to work on the project.

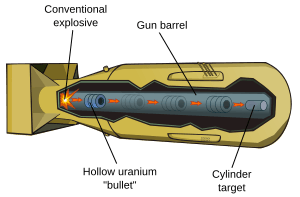

His team designed the "gun-type" plutonium weapon, called "Thin Man." They also worked on a similar design for a uranium-235 weapon. Parsons oversaw tests of these designs.

Later, scientists discovered that the "Thin Man" design wouldn't work for plutonium. This meant they had to quickly develop a new type of bomb called the "implosion-type" weapon, codenamed "Fat Man." Parsons was put in charge of the "O" (ordnance) Division, responsible for both the gun-type bomb (which became "Little Boy") and the delivery of the bombs.

The "Little Boy" uranium bomb was simpler to build. Its design allowed it to be a more normal bomb shape, which made it fly more predictably. Parsons was very focused on making sure the bomb was safe and reliable.

Delivering the Bomb

The plan to deliver the bombs was called Project Alberta. Parsons helped test how the bombs would fly when dropped from B-29 planes. He made sure that the planes were ready to carry these new, heavy weapons. Oppenheimer said that Parsons was almost alone in understanding the real military and engineering problems they would face, and he insisted on solving them early.

In July 1944, Parsons witnessed the Trinity nuclear test, the first explosion of an atomic bomb, from a B-29 plane. Afterward, he flew to Tinian island, where the B-29s of the 509th Composite Group were getting ready for their mission.

On Tinian, Parsons was in charge of the scientists and technicians who handled the nuclear weapons. He, along with Rear Admiral William R. Purnell and Brigadier General Thomas F. Farrell, became known as the "Tinian Joint Chiefs." They made the final decisions for the atomic bomb mission.

Parsons became worried because several B-29s had crashed and burned on the runway. He feared that if a B-29 crashed with the "Little Boy" bomb, the fire could cause a nuclear explosion. He decided that the bomb should be armed after the plane was in the air. The night before the mission, he practiced putting the bomb's parts together in the dark, cramped bomb bay.

On August 6, 1945, Parsons flew on the Enola Gay to Hiroshima. Shortly after takeoff, he climbed into the bomb bay and carefully armed the "Little Boy" bomb. He was in charge of the mission and gave the final approval for the bomb to be released. For his bravery and skill, he received the Silver Star medal and was promoted to commodore. He also received the Navy Distinguished Service Medal for his work on the Manhattan Project.

After the War

After World War II, Parsons continued to play a key role in the Navy's nuclear programs. He was promoted to rear admiral in 1946. He became Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Special Weapons. He strongly supported using nuclear power for warships. He helped set up training for Navy officers, including his former classmate Hyman G. Rickover, who later became known as the "Father of the Nuclear Navy."

In 1946, Parsons was Deputy Commander for Operation Crossroads. This was a series of nuclear weapon tests at Bikini Atoll to see how atomic bombs affected warships. The first test, "Able," was an airburst and didn't sink the main target ship. The second test, "Baker," was an underwater explosion and looked much more dramatic. However, it caused a lot of radioactive fallout, making the target ships unsafe. Parsons received the Legion of Merit for his work on Operation Crossroads.

He continued to work on nuclear weapons development. He served as deputy commander for the Operation Sandstone tests in 1948. In 1951, he finally commanded a group of cruisers, even though he had never commanded a single ship before. He then became Deputy Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance in 1952.

Death and Legacy

William Sterling Parsons died of a heart attack on December 5, 1953, at the age of 52. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery next to his daughter Hannah.

In his memory, the Navy created the Rear Admiral William S. Parsons Award. This award honors Navy or Marine Corps personnel who make outstanding contributions in science and technology. The destroyer USS Parsons was also named in his honor. His wife, Martha, launched the ship in 1958. Later, his daughter Clare, who became a naval officer herself, represented the family when the ship was renamed a guided missile destroyer. The Deak Parsons Center in Norfolk, Virginia, is also named after him.

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |