Guadalcanal campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Guadalcanal campaign |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Solomon Islands campaign of the Pacific Theater of World War II | |||||||

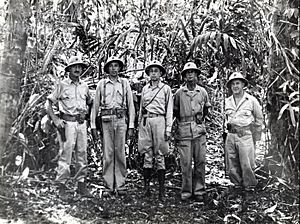

United States Marines rest in the field during the Guadalcanal campaign. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

• • • |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

Robert L. Ghormley William F. Halsey Jr. Richmond K. Turner Frank J. Fletcher Alexander A. Vandegrift William H. Rupertus Merritt A. Edson Alexander M. Patch Russell R. Waesche |

Isoroku Yamamoto Hiroaki Abe Nobutake Kondō Nishizo Tsukahara Takeo Kurita Jinichi Kusaka Shōji Nishimura Gunichi Mikawa Raizō Tanaka Hitoshi Imamura Harukichi Hyakutake |

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| See order of battle | See order of battle | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 60,000+ men (ground forces) | 36,200 men (ground forces) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 7,100 dead 7,789+ wounded 4 captured 29 ships lost including 2 fleet carriers, 6 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers and 17 destroyers. 615 aircraft lost |

Army: 19,200 dead, of whom 8,500 were killed in combat 1,000 captured38 ships lost including 1 light carrier, 2 battleships, 3 heavy cruisers, 1 light cruiser and 11 destroyers. 683 aircraft lost 10,652 evacuated |

||||||

The Guadalcanal campaign, also known as the Battle of Guadalcanal, was a major military fight during World War II. It took place from August 7, 1942, to February 9, 1943, on and around the island of Guadalcanal in the Pacific Ocean. This was the first time Allied forces, mainly from the United States, launched a big land attack against the Empire of Japan.

On August 7, 1942, Allied troops, mostly U.S. Marines, landed on Guadalcanal and nearby islands like Tulagi. Their goal was to use these islands as bases. This would help them eventually capture or weaken the main Japanese base at Rabaul. The Japanese soldiers already on these islands were surprised. The Allies quickly took Tulagi and a new airfield on Guadalcanal. This airfield was later named Henderson Field.

The Japanese tried many times to take back Henderson Field from August to November. There were three big land battles, seven large naval battles, and almost daily air fights. A key moment was the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal in November. The Japanese failed to bomb Henderson Field from the sea or land enough troops to recapture it. In December, Japan decided to give up trying to retake Guadalcanal. They secretly pulled out their remaining forces by February 7, 1943. This happened as the U.S. Army's XIV Corps attacked. The Battle of Rennell Island helped protect the Japanese troops as they left.

The Guadalcanal campaign was a turning point. It showed that the Allies could switch from defending to attacking. It also allowed them to take control of the war in the Pacific from Japan. After this, the Allies launched more attacks in the Pacific. These included campaigns in the Solomon Islands campaign, New Guinea campaign, and the Philippines campaign (1944–1945).

Contents

- Why Guadalcanal Was Important

- Key Events of the Campaign

- Surprise Landings on Guadalcanal

- Naval Battle of Savo Island

- Early Ground Fights

- Battle of the Tenaru River

- Battle of the Eastern Solomons

- The "Tokyo Express" Supply Runs

- Battle of Edson's Ridge

- Allied Reinforcements Arrive

- Fights Along the Matanikau River

- Naval Battle of Cape Esperance

- The Battle for Henderson Field

- Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands

- November Land Actions

- Naval Battle of Guadalcanal

- Japan Decides to Withdraw

- What Happened After

- Guadalcanal Memorials

- Unexploded Bombs on the Island

- Reporting the News

- See also

Why Guadalcanal Was Important

Starting the Pacific War Offensive

On December 7, 1941, Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. This attack killed many people and damaged a large part of the U.S. Navy. The next day, the U.S. declared war on Japan. Japan's main goals were to weaken the U.S. Navy, take control of areas rich in natural resources, and set up military bases. These bases would help defend their empire in the Pacific.

Japan tried to expand its control further south. But two major naval battles stopped them. The first was the Battle of the Coral Sea. This battle was a draw in terms of ships lost, but it was a big win for the Allies. It greatly reduced Japan's ability to use its aircraft carriers. The second was the Battle of Midway. These victories allowed the Allies to start planning their own attacks.

The Allies chose the southern Solomon Islands, including Guadalcanal, as their first target. Japan had taken over Tulagi in May 1942. They were building a seaplane base there. Later, they started building a large airfield on Guadalcanal. This airfield was at Lunga Point. If completed, Japanese bombers from this base could threaten important shipping routes. These routes connected the U.S. to Australia.

The Japanese had about 900 naval troops on Tulagi and nearby islands. On Guadalcanal, they had about 2,800 people. Most of these were Korean forced laborers and Japanese construction workers. These bases would protect Japan's main base at Rabaul. They would also threaten Allied supply lines. Japan planned to send many fighter planes and bombers to Guadalcanal. These planes would help Japan move further into the South Pacific.

Planning the Allied Attack

U.S. Admiral Ernest J. King came up with the plan to invade the southern Solomons. He wanted to stop Japan from using the islands to threaten supply routes. He also wanted to use them as starting points for Allied attacks. The U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt agreed.

The Allies decided that Guadalcanal would be taken. This would happen along with an Allied attack in New Guinea. The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff created the South Pacific theater. Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley took command on June 19. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz was the overall Allied commander.

In May 1942, U.S. Marine Major General Alexander Vandegrift was told to move his 1st Marine Division to New Zealand. Other Allied forces went to bases in Fiji, Samoa, and New Caledonia. Espiritu Santo was chosen as the main base for the attack. The attack was called Operation Watchtower. It was set for August 7.

The Watchtower force had 75 warships and transport ships. These ships were from the U.S. and Australia. They gathered near Fiji on July 26. They practiced landing once before heading to Guadalcanal on July 31. U.S. Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher led the Allied force. Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner commanded the landing forces. Vandegrift led the 16,000 Allied infantry troops. These troops were mostly U.S. Marines. They were new to battle and had limited supplies. They called the operation "Operation Shoestring."

Key Events of the Campaign

Surprise Landings on Guadalcanal

Bad weather helped the Allied forces arrive without being seen by the Japanese. This happened on the night of August 6 and the next morning. The Japanese were completely surprised. The landing force split into two groups. One group attacked Guadalcanal. The other attacked Tulagi, Florida, and nearby islands. Allied warships bombed the beaches. U.S. aircraft bombed Japanese positions and destroyed 15 Japanese seaplanes.

About 3,000 U.S. Marines attacked Tulagi and two small islands, Gavutu and Tanambogo. The Japanese defenders fought fiercely. But the Marines took all three islands by August 9. Almost all the Japanese defenders were killed. The Marines had 248 casualties.

On Guadalcanal, the landings faced much less resistance. On August 7, Vandegrift and 11,000 U.S. Marines landed. They moved towards Lunga Point and met little resistance. They secured the airfield by August 8. The Japanese workers and soldiers had panicked and fled. They left behind food, supplies, and equipment.

On August 7 and 8, Japanese planes from Rabaul attacked the Allied ships. They sank one transport ship and damaged a destroyer. Japan lost 36 aircraft, while the U.S. lost 19. After these attacks, Admiral Fletcher worried about his carrier planes and fuel. He pulled his carrier forces out of the area on the evening of August 8. Because of this, Admiral Turner decided to withdraw his ships too. He left the Marines ashore with many supplies still on the ships.

As the transport ships unloaded on the night of August 8–9, Japanese warships attacked. A force of seven cruisers and one destroyer, led by Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, surprised the Allied ships. They sank one Australian and three American cruisers. One American cruiser and two destroyers were damaged. The Japanese had only minor damage to one cruiser. Mikawa then returned to Rabaul. He worried about U.S. carrier air attacks if he stayed.

Mikawa's choice not to attack the Allied transport ships was a big mistake. If he had, the Marines on Guadalcanal would have been in much worse trouble.

Early Ground Fights

The 11,000 Marines on Guadalcanal focused on building defenses around Lunga Point and the airfield. They moved supplies and finished the airfield. On August 12, the airfield was named Henderson Field. By August 18, it was ready for planes. The Marines had about 14 days of food. They ate two meals a day to save supplies.

Many Marines got dysentery soon after landing. Most of the Japanese and Korean workers who had fled gathered west of the Marine defenses. On August 12, a small U.S. Marine patrol was almost wiped out by Japanese troops. In response, on August 19, the Marines attacked Japanese forces west of the Matanikau River. They killed about 65 Japanese soldiers. This was the first of several fights around the Matanikau River.

On August 20, U.S. planes arrived at Henderson Field. These planes became known as the "Cactus Air Force". They started fighting Japanese air raids the next day.

Battle of the Tenaru River

Japan's Imperial General Headquarters ordered the 17th Army to retake Guadalcanal. Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake led this army. The 17th Army was busy fighting in New Guinea. So, only a few units were available. Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki's regiment was the closest. About 917 of his soldiers landed east of the Marine defenses on August 19. They marched west towards the Marines.

Ichiki's unit attacked Marine positions at Alligator Creek on August 21. They attacked at night, thinking the Allied forces were weaker. A local scout, Jacob C. Vouza, warned the Americans just before the attack. The Marines defeated the Japanese with heavy losses. After sunrise, the Marines counterattacked. Many more Japanese were killed, including Ichiki. About 789 of Ichiki's 917 soldiers died. This battle showed the Japanese that the Americans were stronger than they thought.

Battle of the Eastern Solomons

Japan sent more reinforcements. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto put together a strong force. Their goal was to destroy American ships and Henderson Field. This force left Truk on August 23. Three transport ships carried 1,400 soldiers and 500 naval marines. These ships were guarded by 13 warships led by Rear Admiral Raizō Tanaka. Tanaka planned to land the troops on Guadalcanal on August 24.

To support the landings, Admiral Chūichi Nagumo sent a carrier force from Truk. Nagumo's force had three carriers and 30 other warships. The light carrier Ryūjō was sent ahead to draw American attention.

At the same time, U.S. carrier forces under Admiral Fletcher approached Guadalcanal. On August 24, the two carrier forces fought. Japan had three carriers, while the U.S. had two. The Ryūjō was hit by bombs and a torpedo and sank. The American carrier Enterprise was damaged. Both fleets then pulled back. Japan lost the Ryūjō and many aircraft and aircrew. The U.S. lost fewer planes, and Enterprise needed repairs.

On August 25, Tanaka's convoy was attacked by planes from Henderson Field. One transport ship was sunk, and a destroyer was badly damaged. Tanaka had to turn back. This battle made it impossible for Japan to send supplies to Guadalcanal during the day. They now had to make supply runs only at night. These runs became known as the "Tokyo Express."

The "Tokyo Express" Supply Runs

After the Battle of Savo Island, U.S. Navy ships were ordered not to go to Guadalcanal at night. This was to avoid another big defeat. So, the Japanese controlled the seas around the Solomon Islands at night. They used destroyers to bring troops and some supplies. These runs were called the "Tokyo Express" by the Allies. The Japanese called them "rat transportation."

While troops could be moved this way, heavy equipment, food, and ammunition could not. Any Japanese ship within range of Henderson Field during the day was at high risk of air attack. This situation lasted for several months.

Between August 29 and September 4, Japanese ships landed almost 5,000 troops at Taivu Point. General Kiyotake Kawaguchi took command of all Japanese forces on Guadalcanal.

Battle of Edson's Ridge

On September 7, Kawaguchi planned to attack the American defenses around Henderson Field. His plan was to attack from the south, through the jungle, at night. Meanwhile, local scouts told the U.S. Marines about Japanese troops at Taivu Point. On September 8, Marine forces, led by Merritt A. Edson (Edson's Raiders), raided Taivu. They found Kawaguchi's main supply base. They destroyed it and found documents that showed a large Japanese attack was coming.

Edson believed the Japanese would attack at Lunga Ridge. This was a narrow, grassy ridge south of Henderson Field. It was a good path to the airfield and was not well defended. On September 11, Edson's 840 men were placed on the ridge.

On the night of September 12, Kawaguchi's troops attacked the ridge. The Marines fought back hard. The next night, Kawaguchi attacked again with 3,000 troops. The Japanese charged up the ridge many times. Marines, supported by artillery, fought them off in fierce hand-to-hand combat. Japanese units that got past the ridge were also stopped. By September 14, Kawaguchi's forces were defeated. They lost about 850 men, while the Marines lost 104.

This defeat was a big blow to Japan. The Japanese realized that Guadalcanal was becoming a very important battle. They even pulled back troops from their attack in New Guinea to focus on Guadalcanal.

Allied Reinforcements Arrive

After the battle, the U.S. forces strengthened their defenses. On September 18, an Allied convoy brought 4,157 more Marines and supplies to Guadalcanal. These reinforcements helped Vandegrift create a strong defense line around the Lunga perimeter. During this time, the U.S. aircraft carrier USS Wasp was sunk by a Japanese submarine. This left only one Allied aircraft carrier in the South Pacific.

The air war over Guadalcanal slowed down for a while due to bad weather. Both sides used this time to send more planes. When the air battles started again, the Japanese slowly began to lose more planes and pilots than the Allies.

Fights Along the Matanikau River

The Marines knew that Kawaguchi's troops had retreated west of the Matanikau River. So, they launched more attacks in that area. These attacks aimed to clear out Japanese troops and keep them from getting stronger near the Marine defenses.

From September 23 to 27, U.S. Marines attacked Japanese forces west of the Matanikau. The Japanese fought back, and three Marine companies were surrounded. They suffered heavy losses but managed to escape with help from a destroyer and Coast Guard landing craft. A Coast Guardsman named Douglas Albert Munro was killed while protecting the escaping Marines. He was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Between October 6 and 9, a larger Marine force crossed the Matanikau River. They attacked newly arrived Japanese troops and caused heavy losses. This forced the Japanese to retreat and slowed their plans for another big attack.

Japan continued to send troops to Guadalcanal using the Tokyo Express. The Japanese Navy also promised to support the Army's attack by bombing Henderson Field. Meanwhile, U.S. Army forces were sent to Guadalcanal as reinforcements. To protect these troops, Admiral William Halsey Jr. ordered Task Force 64, led by Rear Admiral Norman Scott, to stop any Japanese ships approaching Guadalcanal.

On the night of October 11, Scott's warships detected a Japanese force. This Japanese force, led by Rear Admiral Aritomo Gotō, was planning to bombard Henderson Field. Scott's ships surprised Gotō's force. They sank one cruiser and one destroyer. Another cruiser was badly damaged, and Gotō was killed. The rest of Gotō's ships retreated. During the fight, one U.S. destroyer was sunk, and two other ships were damaged. The Japanese supply convoy, however, managed to unload its cargo without being found by Scott's force.

The Battle for Henderson Field

Battleship Bombardment

Even after the U.S. victory at Cape Esperance, Japan continued its plans for a big attack. On October 13, a convoy of six cargo ships carrying 4,500 troops and supplies left for Guadalcanal. To protect this convoy, Admiral Yamamoto sent two battleships, Kongō and Haruna, to bomb Henderson Field.

At 1:33 AM on October 14, the battleships opened fire on Henderson Field. For over an hour, they fired nearly 1,000 shells. The bombardment heavily damaged the runways. It also burned almost all the aviation fuel and destroyed 48 of the 90 Allied aircraft. Forty-one men were killed.

Despite the damage, the airfield crew quickly repaired one runway. More U.S. planes were flown in, and fuel was brought from other bases. The Cactus Air Force attacked the Japanese convoy but caused no damage.

The Japanese convoy reached Guadalcanal at midnight on October 14 and began unloading. Throughout October 15, Allied planes from Henderson Field bombed the convoy. They destroyed three cargo ships. The remaining ships left that night. They had unloaded all the troops but only about two-thirds of the supplies. Japanese cruisers also bombed Henderson Field on October 14 and 15, but they did not cause much more damage.

Japanese Ground Attack

Between October 1 and 17, Japan sent 15,000 more troops to Guadalcanal. This gave Hyakutake 20,000 troops for his attack. The Japanese decided to attack Henderson Field from the south, through the jungle. This main attack would be led by General Masao Maruyama with 7,000 soldiers. A smaller force would attack from the west to distract the Americans.

On October 12, Japanese engineers began building a trail through the jungle. This trail, called the "Maruyama Road," was 15 miles long. It went through very difficult terrain. Maruyama's forces began their march on October 16.

By October 23, Maruyama's troops were still struggling through the jungle. Hyakutake had to delay the attack. Meanwhile, the Japanese force in the west attacked the U.S. Marine defenses. But the Marines, with artillery and machine guns, easily stopped them. All the Japanese tanks were destroyed.

Finally, on October 24, Maruyama's forces reached the Lunga perimeter. For two nights, they launched many attacks on the American lines. U.S. Marines and Army troops, using rifles, machine guns, and artillery, caused huge losses to the Japanese. A few small Japanese groups broke through but were quickly killed. More than 1,500 of Maruyama's troops were killed. The Americans lost about 60 men.

On October 26, Hyakutake called off the attacks. He ordered his forces to retreat. The Japanese lost 2,200–3,000 troops in this battle. The Americans lost around 80. This defeat meant the Japanese 2nd Division could no longer launch major attacks.

Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands

While the ground battle was happening, Japanese aircraft carriers and warships moved into position. They hoped to destroy any Allied naval forces, especially carriers. Allied naval forces, now under Admiral William Halsey Jr., also wanted to fight the Japanese.

On October 26, the two carrier forces met in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands. After many air attacks, Allied ships had to retreat. The U.S. lost one carrier, Hornet, and another, Enterprise, was badly damaged. The Japanese carriers also pulled back. They had lost many irreplaceable, experienced aircrews. This was a big long-term advantage for the Allies. After this battle, Japanese carriers did not play a major role in the rest of the campaign.

November Land Actions

After their victory at Henderson Field, the Americans attacked Japanese positions west of the Matanikau River. Their goal was to capture Kokumbona, the Japanese 17th Army headquarters. The Japanese defenders were weak from battle, disease, and lack of food. The American attack began on November 1. They destroyed Japanese forces in the Point Cruz area by November 3. But then, new Japanese troops landed near Koli Point, east of the American defenses. The Americans paused their Matanikau attack to deal with this new threat.

At Koli Point, Japanese destroyers landed 300 soldiers on November 3. These soldiers were to support Colonel Toshinari Shōji's troops. Shōji's unit was heading to Koli Point after the Battle for Henderson Field. The Americans tried to surround Shōji's forces at Gavaga Creek. But Shōji and 2,000 to 3,000 of his men escaped into the jungle through a swampy area. The Americans killed the remaining Japanese soldiers in the pocket. The Americans lost 40 killed, while the Japanese lost 450–475.

Meanwhile, on November 4, U.S. Marine Raiders landed at Aola Bay, east of Lunga Point. They were to protect Seabees building an airfield. This airfield project was later abandoned. The Raiders then marched overland, fighting many of Shōji's retreating forces. They killed almost 500 Japanese. Many more Japanese died from disease and lack of food. By the time Shōji's force reached the Matanikau area, only 700 to 800 survivors remained.

More Japanese troops arrived in November. They helped resist further American attacks near Point Cruz. The two sides faced each other along this line for the next six weeks.

After failing to retake Henderson Field, the Japanese Army planned another attempt in November 1942. They asked Admiral Yamamoto for help. Yamamoto provided 11 large transport ships to carry 7,000 troops and supplies to Guadalcanal. He also sent two battleships, Hiei and Kirishima, to bombard Henderson Field. This was to destroy the airfield and its planes so the transports could unload safely. Vice Admiral Hiroaki Abe commanded this force.

In early November, Allied intelligence learned of Japan's plans. The U.S. sent a large convoy with troops and supplies to Guadalcanal. This convoy was protected by two groups of warships, led by Rear Admirals Daniel J. Callaghan and Norman Scott.

Around 1:30 AM on November 13, Callaghan's force met Abe's bombardment group. The two forces fought at very close range in the dark. Abe's warships sank or badly damaged most of Callaghan's ships. Both Callaghan and Scott were killed. Two Japanese destroyers were sunk, and the Hiei was badly damaged. Despite his victory, Abe ordered his ships to retreat without bombing Henderson Field. The Hiei sank later that day after air attacks. Because Henderson Field was not destroyed, Yamamoto ordered the Japanese troop convoy to wait.

Around 2:00 AM on November 14, a Japanese force from Rabaul bombed Henderson Field. It caused some damage but did not stop the airfield from working. Then, Tanaka's transport convoy headed for Guadalcanal. Throughout November 14, planes from Henderson Field and the Enterprise attacked Tanaka's ships. They sank one heavy cruiser and seven transports. Most of the troops were rescued.

To stop the Japanese, Admiral Halsey sent two battleships, the Washington and South Dakota, led by Admiral Willis Augustus Lee. They reached Guadalcanal just before midnight on November 14. They met a Japanese force led by Admiral Nobutake Kondō. Kondo's force quickly sank three U.S. destroyers and damaged the South Dakota. While the Japanese focused on the South Dakota, the Washington attacked the Kirishima. It hit the Japanese battleship many times, causing fatal damage. Kondo then ordered his ships to retreat without bombing Henderson Field.

As Kondo's ships left, the four remaining Japanese transports beached near Tassafaronga Point at 4:00 AM. U.S. aircraft and artillery attacked them, destroying all four ships and most of their supplies. Only 2,000–3,000 Japanese troops reached shore. Because most of the troops and supplies were lost, Japan had to cancel its November attack on Henderson Field. This was a huge victory for the Allies. It marked the beginning of the end for Japan's attempts to retake Henderson Field.

Japan Decides to Withdraw

Battle of Tassafaronga

The Japanese troops on Guadalcanal were running out of supplies. They were losing about 50 men each day from hunger, disease, and attacks. Japan tried to use submarines to bring supplies, but it wasn't enough. So, they had to go back to using destroyers.

The Japanese came up with a new way to deliver supplies. They would clean oil drums, fill them with food and medicine, and float them to shore. On November 30, Admiral Tanaka's destroyers tried this method. Allied intelligence knew about the supply attempt. Admiral Halsey ordered Task Force 67, led by Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright, to stop Tanaka.

At 10:40 PM on November 30, Tanaka's force arrived off Guadalcanal. Wright's destroyers detected them on radar. Wright's cruisers opened fire, sinking one Japanese destroyer. The rest of Tanaka's ships launched 44 torpedoes at Wright's cruisers. The Japanese torpedoes sank the U.S. cruiser Northampton and heavily damaged three other cruisers. Tanaka's destroyers escaped without damage, but they failed to deliver any supplies.

By December 7, 1942, Japanese forces were in a crisis. More attempts to deliver supplies in December also failed.

Japan's Decision to Leave

On December 12, the Japanese Navy suggested giving up on Guadalcanal. Army officers also agreed that retaking the island was impossible. On December 26, Japan's top leaders decided to withdraw. They started planning a secret evacuation called Operation Ke. On December 31, Emperor Hirohito formally approved the decision.

Final Ground Battles

By December, the tired 1st Marine Division was pulled out. The U.S. XIV Corps took over. This corps included the 2nd Marine Division and two U.S. Army divisions. U.S. Army Major General Alexander Patch replaced Vandegrift as commander. By January, he had over 50,000 men.

On December 18, Allied forces attacked Japanese positions on Mount Austen. A strong Japanese defense called the Gifu stopped them. The Americans paused their attack on January 4. They renewed it on January 10, attacking Mount Austen and two nearby ridges. By January 23, the Allies captured all three. U.S. Marines also advanced along the north coast. The Americans lost about 250 killed, while the Japanese lost around 3,000.

The Ke Evacuation

On January 14, a Tokyo Express run delivered troops to act as a rear guard for the evacuation. Japanese warships and aircraft moved into position. Allied intelligence saw these movements but thought Japan was preparing another attack.

Patch, thinking a big Japanese attack was coming, only sent a small part of his troops to continue attacking. On January 29, Admiral Halsey sent a supply convoy to Guadalcanal. Japanese torpedo bombers attacked that evening and heavily damaged the cruiser Chicago. The next day, more torpedo planes sank the Chicago.

On the night of February 1, 20 Japanese destroyers successfully evacuated 4,935 soldiers from the island. Both sides lost a destroyer during this mission. On the nights of February 4 and 7, the remaining Japanese forces were evacuated. Allied forces were still expecting a big Japanese attack and did not try to stop the evacuation. In total, Japan successfully evacuated 10,652 men. Their last troops left on February 7. Two days later, on February 9, Patch realized the Japanese were gone and declared Guadalcanal secure.

What Happened After

After the Japanese left, Guadalcanal and Tulagi became major Allied bases. They built more runways and naval facilities. These bases helped the Allies move further up the Solomon Islands.

After Guadalcanal, Japan was clearly on the defensive. The constant need to send troops to Guadalcanal weakened Japan's efforts elsewhere. This helped the Allies win battles in New Guinea. The Allies gained a strategic advantage that they never lost. The Guadalcanal campaign ended all Japanese expansion in the Pacific. It put the Allies in a position of clear control. This victory was the first step in a long series of successes that led to Japan's surrender.

The "Europe first" policy meant that the Allies would focus on defeating Germany first. But the success at Guadalcanal convinced President Roosevelt that the Pacific War could also be fought offensively. By the end of 1942, it was clear Japan had lost Guadalcanal. This was a big blow to Japan's plans and an unexpected defeat.

The victory also gave the Allies a huge psychological boost. They had beaten Japan's best forces. After Guadalcanal, Allied soldiers had less fear of the Japanese military. They felt much more hopeful about winning the war in the Pacific. Many Japanese leaders later said that Guadalcanal was the turning point of the war.

Guadalcanal Memorials

The Vilu War Museum is on Guadalcanal, west of Honiara. It has military equipment and aircraft remains. There are memorials for American, Australian, Fijian, New Zealand, and Japanese soldiers who died.

The Guadalcanal American Memorial was opened in Honiara on August 7, 1992. This marked 50 years since the first landings.

Unexploded Bombs on the Island

Many unexploded bombs from the battle are still on Guadalcanal. People living on the island have been killed or hurt by these hidden explosives. The Solomon Islands police have removed most discovered bombs. But clearing them is expensive, and the island does not have enough money. The Solomon Islands have asked the U.S. and Japanese governments for help. In 2012, the U.S. provided funds to help find and remove these bombs. Australia and Norway also have programs to help.

Reporting the News

The Guadalcanal campaign was covered by many talented reporters. News agencies sent their best writers because it was the first major American attack of the war. Richard Tregaskis became famous for his book Guadalcanal Diary. Other famous reporters included Hanson Baldwin from The New York Times, John Hersey from Time and Life, and Ira Wolfert from the North American Newspaper Alliance. The military commander, Vandegrift, gave reporters a lot of freedom. They could go almost anywhere and write what they wanted.

See also

In Spanish: Campaña de Guadalcanal para niños

In Spanish: Campaña de Guadalcanal para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |