Hirohito facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Emperor Shōwa昭和天皇 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Official photograph, 1935

|

|||||||||

| Emperor of Japan | |||||||||

| Reign | 25 December 1926 – 7 January 1989 | ||||||||

| Enthronement | 10 November 1928 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Taishō | ||||||||

| Successor | Akihito | ||||||||

| Prime ministers |

Tanaka Giichi

Hamaguchi Osachi Wakatsuki Reijirō Inukai Tsuyoshi Takahashi Korekiyo (acting) Saitō Makoto Keisuke Okada Kōki Hirota Senjūrō Hayashi Fumimaro Konoe Hiranuma Kiichirō Nobuyuki Abe Mitsumasa Yonai Fumimaro Konoe Hideki Tojo Kuniaki Koiso Kantarō Suzuki Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni Postwar period

Kijūrō Shidehara

Tetsu Katayama Hitoshi Ashida Shigeru Yoshida Ichirō Hatoyama Tanzan Ishibashi Nobusuke Kishi Hayato Ikeda Eisaku Satō Kakuei Tanaka Takeo Miki Takeo Fukuda Masayoshi Ōhira Masayoshi Ito (acting) Zenkō Suzuki Yasuhiro Nakasone Noboru Takeshita |

||||||||

| Prince Regent of Japan | |||||||||

| Regency | 25 November 1921 – 25 December 1926 | ||||||||

| Monarch | Taishō | ||||||||

| Born | Hirohito (裕仁) 29 April 1901 Tōgū Palace, Aoyama, Tokyo, Empire of Japan |

||||||||

| Died | 7 January 1989 (aged 87) Fukiage Palace, Tokyo, Japan |

||||||||

| Burial | 24 February 1989 Musashi Imperial Graveyard, Hachiōji, Tokyo |

||||||||

| Spouse |

Nagako Kuni

(m. 1924) |

||||||||

| Issue |

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||

| House | Imperial House of Japan | ||||||||

| Father | Emperor Taishō | ||||||||

| Mother | Sadako Kujō | ||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||

Emperor Shōwa (昭和天皇 (Shōwa-tennō)), also known by his personal name Hirohito (error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help)), was the 124th emperor of Japan. He ruled from December 25, 1926, until his death in 1989.

Hirohito was the head of state during a very important time in Japan's history. This included Japan's expansion across Asia and its involvement in World War II. After Japan surrendered in 1945, he was not put on trial for war crimes. This was because General Douglas MacArthur believed a cooperative emperor would help Japan become peaceful.

In 1946, the Emperor officially gave up the idea that he was a god. The Constitution of Japan in 1947 stated that the Emperor was only a "symbol of the State." He got his power from the people.

In Japan, emperors are not called by their personal names while they are ruling. Hirohito is now known by his posthumous name, Shōwa. This name also refers to the time period he ruled. He was the longest-reigning Japanese emperor ever.

Contents

Early Life of Emperor Shōwa

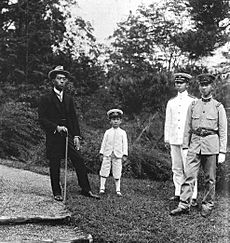

Hirohito was born in Tokyo on April 29, 1901. He was the first son of Crown prince Yoshihito (who became Emperor Taishō) and Crown Princess Sadako (who became Empress Teimei). His childhood name was Prince Michi.

When he was ten weeks old, Hirohito was raised by Count Kawamura Sumiyoshi. At age three, he returned to the imperial court.

In 1908, he started elementary school at the Gakushūin (Peers School). In 1912, at age 11, Hirohito joined the Imperial Japanese Army as a Second Lieutenant. He also joined the Imperial Japanese Navy as an Ensign. When his grandfather, Emperor Meiji, died in 1912, his father, Yoshihito, became emperor.

Crown Prince Era

On November 2, 1916, Hirohito was officially named Crown Prince. This meant he was next in line to become emperor.

Travels Abroad

From March to September 1921, the Crown Prince visited several countries in Western Europe. These included the United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Italy. This was the first time a Japanese Crown Prince had traveled to Western Europe.

He was welcomed in the UK as a friend of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. He met with King George V and Prime Minister David Lloyd George. He also visited famous places like the British Museum and Oxford University.

In Italy, he met with King Vittorio Emanuele III. He also visited battlefields from World War I.

Becoming Regent

After returning to Japan, Hirohito became the Regent of Japan on November 25, 1921. He took over for his father, who was ill.

During his time as regent, several important things happened. Japan, the United States, Britain, and France signed a treaty to keep peace in the Pacific. Japan also agreed to end its alliance with Britain.

In 1923, a huge earthquake, the Great Kantō earthquake, hit Tokyo. On December 27, 1923, a man named Daisuke Namba tried to assassinate Hirohito. But the attempt failed.

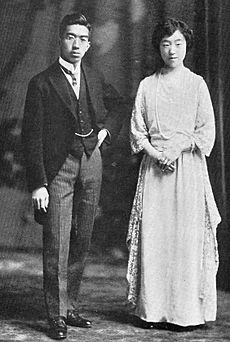

Marriage

Prince Hirohito married his distant cousin Princess Nagako Kuni on January 26, 1924. They had two sons and five daughters.

Their daughters who lived to adulthood left the imperial family. This happened because of changes made to the Japanese imperial household after World War II.

Becoming Emperor

On December 25, 1926, Hirohito became emperor after his father, Yoshihito, died. The era name changed to Shōwa, meaning "Enlightened Peace."

According to Japanese custom, the new Emperor was never called by his personal name. He was simply called "His Majesty the Emperor."

In November 1928, a special ceremony confirmed his role as emperor. This event showed that he had the Imperial Regalia, also known as the Three Sacred Treasures. These treasures had been passed down through centuries.

Early Reign

The first part of Hirohito's reign saw financial problems and the military gaining more power in the government. Between 1921 and 1944, there were 64 separate acts of political violence.

On January 9, 1932, Hirohito narrowly escaped an assassination attempt in Tokyo. A Korean independence activist threw a hand grenade at him.

Another important event was the assassination of Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi in 1932. This marked the end of civilian control over the military. In February 1936, there was an attempted military coup called the February 26 incident. Junior army officers carried it out.

When he heard about the revolt, the Emperor immediately ordered it to be stopped. He called the officers "rebels." The rebellion was stopped on February 29, 1936.

Second Sino-Japanese War

Starting in 1931, Japan began to occupy Chinese territories. This began with the Mukden Incident, where Japan created a false reason to invade Manchuria. The Emperor's military leaders and prime minister, Fumimaro Konoe, recommended this action. Hirohito did not object to the invasion of China.

A diary from a royal attendant suggests that Hirohito was hesitant to start a full war with China in 1937. He worried that Japan had underestimated China's military strength. He said, "once you start (a war), it cannot easily be stopped in the middle."

Some historians say that the Emperor approved the use of chemical weapons against the Chinese. For example, during the Battle of Wuhan in 1938, the use of toxic gas was approved many times. This happened even though the League of Nations had condemned Japan for using toxic gas.

World War II

Getting Ready for War

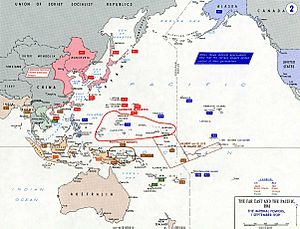

In September 1940, Japan joined the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy. This formed the Axis Powers. The goals were clear: Japan wanted to continue its conquest of China and Southeast Asia. It also wanted to prevent the US or Britain from increasing their military forces in the region.

On September 5, Prime Minister Konoe showed the Emperor a plan for war. The Emperor asked his military leaders about the chances of winning a war against Western countries.

On October 8, the army chief of staff, Sugiyama, gave the Emperor a detailed plan for moving into Southeast Asia. As war preparations continued, Prime Minister Konoe resigned.

The Emperor chose General Hideki Tōjō as the new prime minister. Tojo was known for his loyalty to the Emperor. On November 2, Tojo and other leaders reported to the Emperor that they could not avoid war. Emperor Hirohito then agreed to the war.

On November 3, the plan for the attack on Pearl Harbor was explained to the Emperor. On November 5, Emperor Hirohito approved the war plan against Western countries.

On December 1, an Imperial Conference approved the "War against the United States, United Kingdom and the Kingdom of the Netherlands."

War: Advances and Retreats

On December 8, 1941 (December 7 in Hawaii), Japanese forces attacked Hong Kong, the US Fleet in Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, and began the invasion of Malaya.

The Emperor was very interested in the war's progress. He tried to keep up morale. Some historians say the Emperor was very involved in military operations. For example, he pushed for an early attack on the Philippines. He also ordered new offensives in New Guinea.

As the war turned against Japan in late 1942 and early 1943, the information reaching the palace became less accurate. However, other sources suggest the Emperor was well-informed about Japan's military situation.

The media, which was controlled by the government, always showed the Emperor boosting morale. Even when Japanese cities were heavily bombed, the media reported victories. Slowly, people realized the situation was very bad. There were shortages of food, medicine, and fuel. American air raids on major cities showed that the stories of victory were not true.

Surrender

In early 1945, after losses in the Battle of Leyte, Emperor Hirohito met with officials to discuss the war. Most advised continuing the war. But former Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe urged a surrender. He feared a communist revolution more than defeat.

As weeks passed, victory became less likely. In April, the Soviet Union said it would not renew its neutrality agreement with Japan. Germany, Japan's ally, surrendered in May 1945. In June, the Japanese cabinet decided to fight to the very end.

On June 22, the Emperor told his ministers, "I desire that concrete plans to end the war... be speedily studied." However, attempts to negotiate peace through the Soviet Union failed. On July 26, 1945, the Allies issued the Potsdam Declaration. It demanded Japan's unconditional surrender. The Japanese government considered it but wanted to keep the Emperor's position. The Emperor decided not to surrender.

This changed after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet Union declaring war on Japan. On August 9, Emperor Hirohito was told about the Soviet attack. On August 10, the cabinet drafted an "Imperial Rescript ending the War." It followed the Emperor's wishes to keep his power as a ruler.

On August 12, 1945, the Emperor told his family he would surrender. On August 14, the government told the Allies that it accepted the Potsdam Declaration.

On August 15, a recording of the Emperor's surrender speech was broadcast on the radio. This was the first time the Japanese people heard the Emperor's voice on the radio. He announced Japan's acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration. He said the enemy had used a "new and most cruel bomb." He also stated that continuing to fight would destroy the Japanese nation and human civilization. The speech used formal, old Japanese, so many common people did not fully understand it.

A group in the army tried to stage a coup d'état on August 14. They seized the Imperial Palace. But the recording of the Emperor's speech was hidden and saved. The coup failed, and the speech was broadcast the next morning.

After Japan surrendered, some Allied countries and Japanese leftists wanted the Emperor to be tried as a war criminal. However, General Douglas MacArthur believed that keeping the Emperor on the throne would help Japan accept the Allied occupation. So, evidence that might have blamed the Emperor was kept out of the war crime trials.

Postwar Reign

General Douglas MacArthur insisted that Emperor Hirohito remain on the throne. MacArthur saw the Emperor as a symbol of Japanese unity. Some historians criticize the decision to clear the Emperor and his family members from war crime charges.

Before the war crime trials, Allied and Japanese officials worked to prevent the Imperial family from being charged. They also influenced witnesses' statements to protect the Emperor.

Imperial Status

Hirohito was not put on trial. But he had to officially reject the idea that the Emperor of Japan was a living god. This belief came from Shinto religion, which said the Imperial Family were descendants of the sun goddess Amaterasu.

The 1947 Constitution formally changed the Emperor's role. It defined him as "the symbol of the state and the unity of the people." It took away his power in government matters. His role became limited to state duties, usually following the Cabinet's instructions.

After 1979, Hirohito became the only monarch in the world with the title "emperor."

Public Figure

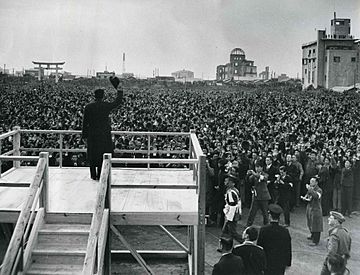

For the rest of his life, Hirohito was an active public figure in Japan. He performed many duties of a constitutional head of state. He and his family often appeared in public. For example, in 1947, the Emperor visited Hiroshima and gave a speech. He encouraged the city's citizens.

He also helped rebuild Japan's image abroad. He traveled to meet many foreign leaders. These included Queen Elizabeth II (1971) and President Gerald Ford (1975). He was the first reigning emperor to travel outside Japan. He was also the first to meet a US President.

| Year | Departure | Return | Visited | Accompany | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 (Shōwa 46) |

27 September | 14 October | Empress Kōjun | International friendship | |

| 1975 (Shōwa 50) |

30 September | 14 October | Empress Kōjun | International friendship |

Visit to Europe

In 1971, the Emperor visited seven European countries. These included the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. He traveled by plane this time, unlike his earlier visit by ship. He also stopped in Anchorage, Alaska, and met with US President Richard Nixon.

The meeting with President Nixon was not originally planned. It was decided quickly at the request of the United States.

In some countries, like Britain and the Netherlands, there were protests. Veterans and victims of the war protested his visit. In the Netherlands, people threw eggs. In the UK, protestors turned their backs as his carriage passed. Despite this, the Emperor said he was not surprised and felt the welcome was still important.

Visit to the United States

In 1975, the Emperor visited the United States for two weeks. This was at the invitation of President Gerald Ford. It was the first time a Japanese Emperor had visited the US.

During his visit, he met President Ford. He also visited Arlington National Cemetery. In a speech at the White House, Hirohito thanked the United States for helping Japan rebuild after the war. He also visited Disneyland in Los Angeles. A photo of him smiling next to Mickey Mouse appeared in newspapers. This was his last visit to the United States.

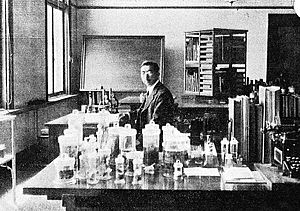

Marine Biology Research

The Emperor was very interested in marine biology. He had a laboratory at the Tokyo Imperial Palace. From there, he published several scientific papers under his personal name, "Hirohito." He described many new species of Hydrozoa.

Yasukuni Shrine

The Emperor stopped visiting the Yasukuni Shrine in 1978. This was because it was revealed that Class-A war criminals had been secretly honored there. He continued this boycott until his death. His successors, Akihito and Naruhito, have also continued it.

A memorandum from 2006 confirmed the reason for the boycott. It showed that the Emperor was very unhappy about the war criminals being enshrined. He said he had not visited the shrine since then.

Death and State Funeral

On September 22, 1987, the Emperor had surgery for duodenal cancer. He seemed to recover well for several months. But on September 19, 1988, he collapsed. His health worsened due to internal bleeding.

The Emperor died on January 7, 1989, at age 87. He was survived by his wife, five children, ten grandchildren, and one great-grandchild.

At the time of his death, he was the longest-lived and longest-reigning Japanese emperor. He was also the longest-reigning monarch in the world.

His eldest son, Akihito, became the new emperor. The Emperor's death also marked the end of the Shōwa era. A new era, the Heisei era, began the next day.

On February 24, 1989, the Emperor's state funeral was held. Many world leaders attended. Hirohito is buried in the Musashi Imperial Graveyard in Hachiōji.

Titles, Styles, Honours and Arms

Military Appointments

- Grand Marshal and Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Empire of Japan, December 25, 1926

Foreign Military Appointments

United Kingdom: Honorary General in the British Army, May 1921

United Kingdom: Honorary General in the British Army, May 1921 United Kingdom: Field-Marshal of the Regular Army in the British Army, June 1930

United Kingdom: Field-Marshal of the Regular Army in the British Army, June 1930

National Honours

- Founder of the Order of Culture, February 11, 1937

Foreign Honours

Germany: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, Special Class (GCBVO)

Germany: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, Special Class (GCBVO) Finland: Grand Cross of the Order of the White Rose of Finland, with Collar, 1942

Finland: Grand Cross of the Order of the White Rose of Finland, with Collar, 1942 Norway: Grand Cross of the Royal Norwegian Order of Saint Olav (StkStOO), with Collar, September 26, 1922

Norway: Grand Cross of the Royal Norwegian Order of Saint Olav (StkStOO), with Collar, September 26, 1922 Sweden: Knight of the Royal Order of the Seraphim (RSerafO), with Collar, May 8, 1919

Sweden: Knight of the Royal Order of the Seraphim (RSerafO), with Collar, May 8, 1919 Denmark: Knight of the Order of the Elephant (RE), January 24, 1923

Denmark: Knight of the Order of the Elephant (RE), January 24, 1923 Poland: Knight of the Order of the White Eagle, 1922

Poland: Knight of the Order of the White Eagle, 1922 Thailand: Knight of the Most Auspicious Order of the Rajamitrabhorn (KRMBh), May 27, 1963

Thailand: Knight of the Most Auspicious Order of the Rajamitrabhorn (KRMBh), May 27, 1963 Thailand: Knight of the Most Illustrious Order of the Royal House of Chakri (KMChk), January 30, 1925

Thailand: Knight of the Most Illustrious Order of the Royal House of Chakri (KMChk), January 30, 1925 Nepal: Member of the Most Glorious Order of Ojaswi Rajanya, April 19, 1960

Nepal: Member of the Most Glorious Order of Ojaswi Rajanya, April 19, 1960 Philippines: Grand Collar of the Order of Sikatuna, September 28, 1966

Philippines: Grand Collar of the Order of Sikatuna, September 28, 1966 Brazil: Grand Cross of the National Order of the Southern Cross, 1955

Brazil: Grand Cross of the National Order of the Southern Cross, 1955 Italian Royal Family: Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, October 31, 1916

Italian Royal Family: Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, October 31, 1916 Italy: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (OMRI), with Collar, March 9, 1982

Italy: Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (OMRI), with Collar, March 9, 1982 Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold Malaysia: Honorary Member of the Order of the Crown of the Realm (DMN), 1964

Malaysia: Honorary Member of the Order of the Crown of the Realm (DMN), 1964 Tonga: Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Pouono (KGCCP), with Collar

Tonga: Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Pouono (KGCCP), with Collar United Kingdom: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (GCVO), May 1921

United Kingdom: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (GCVO), May 1921 United Kingdom: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath (civil division) (GCB), May 1921

United Kingdom: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath (civil division) (GCB), May 1921 United Kingdom: Stranger Knight of the Most Noble Order of the Garter (KG), May 3, 1929; revoked, 1941; restored, May 22, 1971

United Kingdom: Stranger Knight of the Most Noble Order of the Garter (KG), May 3, 1929; revoked, 1941; restored, May 22, 1971 United Kingdom: Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS), 1971

United Kingdom: Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS), 1971 Brunei: Member of the Order of the Crown of Brunei, 1st Class

Brunei: Member of the Order of the Crown of Brunei, 1st Class Spain: Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, October 6, 1928

Spain: Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, October 6, 1928 Spain: Grand Cross of the Royal and Distinguished Order of Charles III, with Collar, June 4, 1923

Spain: Grand Cross of the Royal and Distinguished Order of Charles III, with Collar, June 4, 1923 Greek Royal Family: Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer

Greek Royal Family: Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer Greek Royal Family: Grand Cross of the Royal Family Order of Saints George and Constantine, with Collar

Greek Royal Family: Grand Cross of the Royal Family Order of Saints George and Constantine, with Collar Czechoslovakia: Collar of the Order of the White Lion, 1928

Czechoslovakia: Collar of the Order of the White Lion, 1928 Ethiopian Imperial Family: Collar of the Order of Solomon

Ethiopian Imperial Family: Collar of the Order of Solomon Russian Imperial Family: Knight of the Order of Saint Andrew the Apostle the First-called, September 1916

Russian Imperial Family: Knight of the Order of Saint Andrew the Apostle the First-called, September 1916

Issue

Emperor Shōwa and Empress Kōjun had seven children, two sons and five daughters.

| Name | Birth | Death | Marriage | Children | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Spouse | ||||

| Shigeko Higashikuni (Shigeko, Princess Teru) |

9 December 1925 | 23 July 1961 | 10 October 1943 | Prince Morihiro Higashikuni |

|

| Sachiko, Princess Hisa | 10 September 1927 | 8 March 1928 | None | ||

| Kazuko Takatsukasa (Kazuko, Princess Taka) |

30 September 1929 | 26 May 1989 | 20 May 1950 | Toshimichi Takatsukasa | Naotake Takatsukasa (adopted) |

| Atsuko Ikeda (Atsuko, Princess Yori) |

7 March 1931 | 10 October 1952 | Takamasa Ikeda | None | |

| Akihito, Emperor Emeritus of Japan (Akihito, Prince Tsugu) |

23 December 1933 | 10 April 1959 | Michiko Shōda |

|

|

| Masahito, Prince Hitachi (Masahito, Prince Yoshi) |

28 November 1935 | 30 September 1964 | Hanako Tsugaru | None | |

| Takako Shimazu (Takako, Princess Suga) |

2 March 1939 | 10 March 1960 | Hisanaga Shimazu | Yoshihisa Shimazu | |

Scientific Publications

- (1967) A review of the hydroids of the family Clathrozonidae with description of a new genus and species from Japan.

- (1969) Some hydroids from the Amakusa Islands.

- (1971) Additional notes on Clathrozoon wilsoni Spencer.

- (1974) Some hydrozoans of the Bonin Islands.

- (1977) Five hydroid species from the Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea.

- (1983) Hydroids from Izu Oshima and Nijima.

- (1984) A new hydroid Hydractinia bayeri n. sp. (family Hydractiniidae) from the Bay of Panama.

- (1988) The hydroids of Sagami Bay collected by His Majesty the Emperor of Japan.

- (1995) The hydroids of Sagami Bay II. (posthumous)

See also

In Spanish: Hirohito para niños

In Spanish: Hirohito para niños

- Japanese nationalism

- Otoya Yamaguchi

- The Sun – a biographical film about the Emperor

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |