February 26 incident facts for kids

Quick facts for kids February 26 incident |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

1st Lt. Nibu Masatada and his company

on February 26, 1936 |

|||

| Date | 26–28 February 1936 | ||

| Location | |||

| Goals |

|

||

| Resulted in | Uprising suppressed

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Number | |||

|

|||

The February 26 Incident (also known as the 2–26 Incident) was an attempted coup d'état in Japan on February 26, 1936. A group of young officers from the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) organized it. Their goal was to remove certain leaders from the government and military. They wanted to get rid of people who disagreed with their ideas.

The rebels managed to kill several important officials. These included two former prime ministers. They also took control of the government area in Tokyo. However, they failed to kill Prime Minister Keisuke Okada. They also could not take control of the Imperial Palace. Some people in the army tried to support the rebels. But there were disagreements within the military. The Emperor was also very angry about the coup. This meant the rebels could not change the government.

The army moved against them, and the rebels faced strong opposition. They surrendered on February 29. This coup attempt had serious results. After secret trials, nineteen leaders of the uprising were executed. They were found guilty of mutiny, which means rebelling against authority. Forty others were sent to prison. The radical Kōdō-ha group lost its power in the army. The military then gained more control over the civilian government. This government was already weak because key moderate leaders had been killed.

Contents

Why the Uprising Happened

Army Groups and Rivalries

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) had a long history of groups disagreeing. By the early 1930s, high-ranking officers were split into two main informal groups. One was the Kōdō-ha (meaning "Imperial Way") led by General Sadao Araki. The other was the Tōsei-ha (meaning "Control") group.

The Kōdō-ha believed in the importance of Japanese culture. They thought spiritual purity was more important than material things. They wanted to attack the Soviet Union. The Tōsei-ha officers were influenced by Nazi Germany's military ideas. They supported central planning for the economy and military. They also wanted to modernize the army with new technology. They aimed to expand Japan's influence in China. The Kōdō-ha group was powerful in the army when Araki was Minister of War from 1931 to 1934. But many of its members were replaced by Tōsei-ha officers after Araki resigned.

The "Young Officers"

The IJA officers were divided by their education. Some went to the Imperial Japanese Army Academy (an undergraduate school). Others went to the more advanced Army War College. The War College graduates became the elite officers. Those from the Army Academy usually could not reach higher positions. Many of these less privileged officers became part of a political group. They were called the "young officers."

These young officers believed Japan had lost its way. They thought "privileged classes" were exploiting people. This led to poverty in rural areas. They also believed these classes were tricking the Emperor. They thought this weakened Japan. Their solution was a "Shōwa Restoration." This was like the Meiji Restoration from 70 years before. They believed that by rising up, they could remove "evil advisers" around the Emperor. This would allow the Emperor to regain his power. Then, the Emperor would remove those who exploited the people. This would bring back prosperity to the nation. These ideas were influenced by nationalism. Many of the young officers' soldiers came from poor families. They felt the young officers understood their problems.

This group of young officers had about 100 regular members. Most were officers in the Tokyo area. Their informal leader was Mitsugi Nishida. He was a former army lieutenant. Nishida was a key member of nationalist groups in Japan. This group was called the Kokutai Genri-ha. They were involved in much of the political violence of that time. After incidents in 1931, the army and navy members of the group mostly stopped working with civilian nationalists.

Even though it was small, the Kokutai Genri-ha group was influential. They had supporters among high-ranking army officers. They also had support from the Imperial Family. Prince Chichibu, the Emperor's brother, was friends with their leaders. The group was against capitalism. But they still got money from rich business leaders (zaibatsu). These businesses hoped to protect themselves.

The Kōdō-ha and Kokutai Genri-ha were different groups. But they worked together. The Kōdō-ha protected the Kokutai Genri-ha. In return, the Kōdō-ha benefited from being seen as able to control the radical young officers.

Planning the Uprising

Why They Decided to Act

The Kokutai Genri-ha had long wanted a violent uprising. They decided to act in February 1936 for two main reasons. First, the 1st Division, where most of their officers served, was going to move to Manchuria. This meant they had to act soon or wait years. Second, a trial for an officer named Aizawa was happening. The young officers felt public opinion was on their side. They thought acting during his trial would help them.

Nishida and Kita first opposed the plan. Their connection with the officers had weakened. But once it was clear the officers would act, they supported them. Another challenge was getting troops. Teruzō Andō had promised his commander not to involve his men. But Muranaka and Nonaka talked to him repeatedly. They eventually convinced him. Andō's position was key because his regiment had the most troops.

February 26 was chosen because the officers could arrange to be on duty that day. This made it easier to get weapons and ammunition. The date also allowed Mazaki to testify at Aizawa's trial on February 25.

The Plan and Manifesto

The uprising was planned in meetings from February 18 to 22. The plan was simple. The officers would kill the main enemies of the kokutai. They would take control of the capital's government center and the Imperial Palace. Then, they would present their demands. These included removing certain officers and appointing a new government led by Mazaki. They had no long-term goals. They believed the Emperor should decide those. Some think they were ready to replace Hirohito with Prince Chichibu if needed.

The young officers believed they had quiet approval from important army officers. These included Araki, Minister of War Yoshiyuki Kawashima, and General Jinzaburō Mazaki. Kawashima's successor later said that if all supporting officers had resigned, there would not have been enough high-ranking officers left.

The young officers wrote a document explaining their goals. It was called the "Manifesto of the Uprising." They wanted it given to the Emperor. The document blamed older statesmen (genrō), political leaders, and military groups. It also blamed big businesses (zaibatsu) and political parties. It said they were selfish and disrespected the Emperor. This was endangering the kokutai. The manifesto called for direct action:

Now, as we are faced with great emergencies both foreign and domestic, if we do not execute the disloyal and unrighteous who threaten the kokutai, if we do not cut away the villains who obstruct the Emperor's authority, who block the Restoration, the Imperial plan for our nation will come to nothing [...] To cut away the evil ministers and military factions near the Emperor and destroy their heart: that is our duty and we will complete it.

They chose seven targets to kill. They believed these people were "threatening the kokutai":

| Name | Position | Reasons for Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Keisuke Okada | Prime Minister | Supported the London Naval Treaty, supported the "organ theory" of the kokutai. |

| Saionji Kinmochi | Genrō, former Prime Minister | Supported the London Naval Treaty, caused the Emperor to form improper cabinets. |

| Makino Nobuaki | former Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal | Supported the London Naval Treaty, prevented Prince Fushimi from protesting to the Emperor. |

| Kantarō Suzuki | Grand Chamberlain | Supported the London Naval Treaty, "obstructing the Imperial virtue." |

| Saitō Makoto | Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, former Prime Minister | Supported the London Naval Treaty, involved in Mazaki's dismissal. |

| Takahashi Korekiyo | Finance Minister, former Prime Minister | Involved in party politics, tried to weaken the military, kept the old economic system. |

| Jōtarō Watanabe | Inspector General of Military Education | Supported the "organ theory" of the kokutai, refused to resign. |

The first four people on the list survived the attacks. Saionji, Saitō, Suzuki, and Makino were targeted because they were important Imperial advisers. Okada and Takahashi were moderate political leaders. They had tried to limit the military's power. Watanabe was targeted because he was part of the Tōsei-ha group. He was also involved in Mazaki's removal.

Saionji's name was later removed from the list. Some thought he should be kept alive to help convince the Emperor to appoint Mazaki as prime minister.

The Righteous Army

From February 22, seven leaders convinced eighteen other officers to join. Non-commissioned officers (NCOs) were told on the night of February 25, just hours before the attacks. The officers said all NCOs joined willingly. But many NCOs later said they felt they had no choice. The soldiers themselves, many new from basic training, were not told anything until the coup began.

Most of the Righteous Army came from the 1st Division's 1st Infantry Regiment (456 men) and 3rd Infantry Regiment (937 men). Another 138 men came from the 3rd Imperial Guard Regiment. Including officers, civilians, and others, the Righteous Army had 1,558 men.

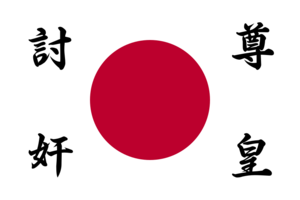

The coup leaders called their force the "Righteous Army." Their password was "Revere the Emperor, Destroy the Traitors." This was similar to a slogan from the Meiji Restoration.

The Uprising Begins

On the night of February 25, heavy snow fell in Tokyo. This made the rebel officers feel hopeful. It reminded them of an event in 1860. In that event, political activists (shishi) killed a chief adviser to the Shōgun in the Emperor's name.

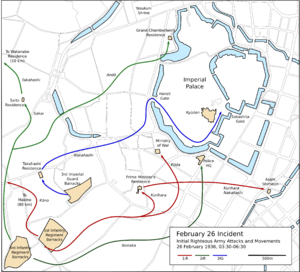

The rebel troops, split into six groups, left their barracks between 3:30 AM and 4:00 AM. The attacks on Okada, Takahashi, Suzuki, Saitō, the Ministry of War, and the Tokyo Metropolitan Police headquarters all happened at 5:00 AM.

Attacks by the 1st Infantry Regiment

Prime Minister Okada's Residence

About 280 men from the 1st Infantry Regiment attacked Prime Minister Okada's residence. They surrounded the building and forced the guards to open the gates. Inside, four policemen fired at them. The police were killed, but they wounded six rebel soldiers. This gunfire warned Okada. His brother-in-law, Colonel Denzō Matsuo, hid him. Matsuo looked like Okada. The soldiers found and killed Matsuo. They thought he was Okada. Okada escaped the next day, but this was kept secret. After Matsuo's death, the rebels guarded the compound.

Seizing the Ministry of War

Captain Kiyosada Kōda led 160 men to take control of the Minister of War's residence, the Ministry of War, and the General Staff Office. They entered the residence and met Minister Kawashima. They read their manifesto and gave him a list of demands. These included preventing force against them and arresting certain officers. They also demanded Araki be made the new commander of the Kwantung Army.

During this time, several officers who supported the rebels arrived. These included General Mazaki and General Tomoyuki Yamashita. Minister Kawashima said he needed to speak with the Emperor. He left for the Imperial Palace.

Attack on Makino Nobuaki

Captain Hisashi Kōno led a team to attack Makino. Makino was staying at an inn in Yugawara. The team arrived at 5:45 AM. Police inside the inn opened fire, starting a gunfight. A policeman warned Makino and helped him escape through a back entrance. The attackers fired but did not realize Makino had gotten away. Kōno was wounded. The attackers then set the building on fire. The men took Kōno to a military hospital, where they were all arrested.

Attack on the Asahi Shimbun Newspaper

Around 10:00 AM, Kurihara and Nakahashi took sixty men to the offices of the Asahi Shimbun. This was a major liberal newspaper. The officers forced the employees out. They yelled that the attack was "divine retribution" for being an "un-Japanese newspaper." They then scattered the newspaper's metal type pieces on the floor. This stopped the newspaper from publishing for a time. After the attack, the men gave copies of their manifesto to other newspapers. Then they returned to the Prime Minister's Residence.

Attacks by the 3rd Imperial Guard

Takahashi Korekiyo

1st Lieutenant Motoaki Nakahashi led 135 men from the 3rd Imperial Guard. He told his commanders they were going to a shrine. Instead, they marched to Takahashi's home. Nakahashi and another lieutenant found Takahashi sleeping in his bedroom. Nakahashi shot Takahashi with his pistol. The other lieutenant slashed him with his sword. Takahashi died without waking.

After Takahashi was dead, Nakahashi sent some men to join the troops at the Prime Minister's Residence. He then took the remaining men to the Imperial Palace.

Attempt to Secure the Imperial Palace

Nakahashi and his 75 men entered the palace grounds at 6:00 AM. Nakahashi told the palace guard commander that he was sent to reinforce the gates. The commander knew about the attacks, so he was not surprised. Nakahashi was assigned to guard the main entrance to the Emperor's residence.

Nakahashi planned to secure the gate and signal nearby rebel troops. This would give them control over who saw the Emperor. But Nakahashi had trouble contacting his allies. By 8:00 AM, the commander learned of Nakahashi's involvement. Nakahashi was ordered to leave the palace grounds. He did so, joining Kurihara at the Prime Minister's Residence. His soldiers stayed at the gate until 1:00 PM. Then they returned to their barracks.

Attacks by the 3rd Infantry Regiment

Saitō Makoto

1st Lieutenant Naoshi Sakai led 120 men from the 3rd Infantry Regiment to Saitō's home. Soldiers surrounded the police guards, who surrendered. Five men entered the house and found Saitō and his wife. They shot Saitō, who died. His wife tried to protect him and was wounded. After Saitō's death, some officers went to attack General Watanabe. The rest took a position near the Ministry of War.

Kantarō Suzuki

Captain Teruzō Andō led 200 men from the 3rd Infantry Regiment to Suzuki's home. They disarmed the police guards. A group entered the building and found Suzuki in his bedroom. He was shot twice. Andō then moved to kill him with his sword. But Suzuki's wife asked to do it herself. Believing Suzuki was dying, Andō agreed. He apologized to her, saying it was for the nation. He then ordered his men to salute Suzuki. They left to guard a junction north of the Ministry of War. Suzuki, though badly wounded, survived.

Andō had visited Suzuki in 1934. He had suggested Araki be made prime minister. Suzuki rejected the idea, but Andō had a good impression of him.

Watanabe Jōtarō

After the attack on Saitō, twenty men went to Watanabe's home. They arrived shortly after 7:00 AM. No one had warned Watanabe.

As the men tried to enter the front, military police inside fired at them. Two soldiers were wounded. The soldiers then forced their way in through the back. They found Watanabe's wife. Pushing her aside, they found Watanabe using a futon for cover. Watanabe fired his pistol. One soldier fired a machine gun at him. Another soldier then killed Watanabe with his sword. The soldiers left, taking their wounded to a hospital. They then took a position in northern Nagatachō.

Tokyo Metropolitan Police Headquarters

Captain Shirō Nonaka took about 500 men from the 3rd Infantry Regiment. They attacked the Tokyo Metropolitan Police headquarters. Their goal was to secure its communication equipment. They also wanted to stop the police's Emergency Service Unit. They met no resistance and quickly took the building. This was likely because the police decided to let the army handle the situation. Nonaka's group was large because they were meant to move on to the palace.

After taking the police headquarters, a small group attacked the home of Fumio Gotō, the Home Minister. Gotō was not home and escaped. This attack seems to have been a separate decision by the officer leading it.

After the Uprising

Trials and Consequences

On March 4, 1936, the Emperor approved a Special Court Martial. This court would try those involved in the uprising. All 1,483 members of the Righteous Army were questioned. But only 124 were charged. These included nineteen officers, 73 NCOs, nineteen soldiers, and ten civilians. All officers, 43 NCOs, three soldiers, and all civilians were found guilty. The trials took almost eighteen months.

The main trial for the rebellion's leaders began on April 28. This trial was held in secret. The defendants could not have lawyers, call witnesses, or appeal. The judges did not want to hear about the defendants' reasons. They made them focus only on their actions. The rebels were charged with rebellion. The officers argued their actions were approved by the Minister of War. They also said they were part of the martial law forces. They claimed they were never formally given the Emperor's command to stop. The verdicts were given on June 4. The sentences were given on July 5. All were found guilty, and seventeen were sentenced to death.

More trials were held for those directly involved in the attacks. Trials were also held for 37 men who supported the rebellion indirectly. Twenty-four were found guilty. Their punishments ranged from life imprisonment to fines.

Kita and Nishida were also charged as leaders of the rebellion. They were tried separately. Their actions during the uprising were mostly indirect, like phone calls. So, they did not actually meet the requirements for the charge. However, the Tōsei-ha generals, who now controlled the army, decided these two men's influence had to be removed. They were sentenced to death on August 14, 1937.

The only important military figure tried for involvement was Mazaki. He was charged with working with the rebel officers. Even though his own testimony showed he was guilty, he was found not guilty on September 25, 1937. This may have been due to the influence of Fumimaro Konoe, who became prime minister in June.

Fifteen officers were executed by firing squad on July 15 at a military prison. The executions of Muranaka and Isobe were delayed. This was so they could testify at Kita and Nishida's trial. Muranaka, Isobe, Kita, and Nishida were executed by firing squad on August 14, 1937.

Changes in Government and Army Leadership

Even though the coup failed, the February 26 Incident greatly increased the military's power over the civilian government. The Okada government resigned on March 9. A new government was formed by Kōki Hirota. General Hisaichi Terauchi, the new Minister of War, showed he was unhappy with some of Hirota's choices for the government. Hirota gave in to Terauchi's demands and changed his selections.

This interference led to a new rule. Only active-duty officers could serve as Minister of War and Minister of the Navy. Before this, retired officers could hold these positions. This rule was accepted on May 18. This change had big effects on the Japanese government. It gave the military services power over government policies. If a minister resigned, and the military refused to appoint a new officer, the government could fall. This happened to Hirota less than a year later.

Under Terauchi, "reform staff officers" began to remove people from the military. Nine of the twelve full generals in the army were removed by the end of April. These included Kōdō-ha members like Araki and Mazaki. Other Kōdō-ha officers were also removed or sent away from Tokyo. This made it harder for them to influence policy. The goal was clearly to remove the Kōdō-ha's influence. Almost every high-ranking officer who had supported the Righteous Army was affected.

Remembering the Incident

The families of the executed rebels were not allowed to remember them until after World War II. They formed a group called the Busshinkai. They have set up two sites in Tokyo to remember the officers of the February 26 Incident. In 1952, they placed a gravestone called "Grave of the Twenty-two Samurai" in a temple. This is where the ashes of the executed men were placed. The "twenty-two" refers to the nineteen executed men, the two who died by their own hand, and Aizawa. Then, in 1965, they placed a statue of Kannon, the Buddhist goddess of mercy. This statue is dedicated to the rebel officers and their victims.[[[Category:Democratic backsliding in the interwar period]]

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |