Tomoyuki Yamashita facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Tomoyuki Yamashita

|

|

|---|---|

|

山下 奉文

|

|

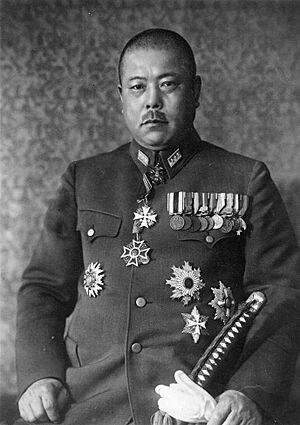

Yamashita in the 1940s

|

|

| Military Governor of Japan to the Philippines | |

| In office 26 September 1944 – 2 September 1945 |

|

| Monarch | Emperor Shōwa |

| Preceded by | Shigenori Kuroda |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 8 November 1885 Ōtoyo, Kōchi, Empire of Japan |

| Died | 23 February 1946 (aged 60) Los Baños, Laguna, Commonwealth of the Philippines |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Resting place | Tama Reien Cemetery, Fuchū, Tokyo, Japan |

| Alma mater | Imperial Japanese Army Academy |

| Awards | Order of the Golden Kite Order of the Rising Sun Order of the Sacred Treasure Order of the German Eagle |

| Nicknames | Tiger of Malaya The Beast of Bataan |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1905–1945 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | 25th Army 1st Area Army 14th Area Army |

| Battles/wars | World War I Second Sino-Japanese War Pacific War |

Tomoyuki Yamashita (山下 奉文, Yamashita Tomoyuki, 8 November 1885 – 23 February 1946; also called Tomobumi Yamashita) was a Japanese general during World War II. He led Japanese forces during the quick invasion of Malaya and the Battle of Singapore. His success in capturing Malaya and Singapore in just 70 days earned him the nickname "The Tiger of Malaya." The British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, called the fall of Singapore the "worst disaster" in British military history.

Later in the war, Yamashita was sent to defend the Philippines from the advancing Allied forces. Even though his supplies were low and Allied guerrillas were active, he held onto parts of Luzon until Japan officially surrendered in August 1945.

After the war, Yamashita was put on trial for war crimes. These crimes were committed by troops under his command in the Philippines in 1944. Yamashita said he did not order these crimes and did not know they were happening. However, the court found him guilty. He was executed in February 1946. The court's decision, which held a commander responsible for crimes committed by their soldiers even if they didn't order them, became known as the Yamashita standard.

Contents

Tomoyuki Yamashita's Life

Yamashita was born in 1885 in a village in Kōchi Prefecture, Japan. He was the second son of a local doctor. From a young age, he attended military schools to prepare for a career in the army.

Starting His Military Career

In November 1905, Yamashita finished his studies at the Imperial Japanese Army Academy. He was one of the top students in his class. He became a lieutenant in December 1908. He fought against the German Empire in World War I in China in 1914. By May 1916, he was promoted to captain.

Yamashita continued his military education at the Army War College. He graduated in 1916. He became an expert on Germany, working as a military helper in Bern and Berlin from 1919 to 1922. In February 1922, he became a major.

Yamashita worked in the War Ministry, trying to make the Japanese army more efficient. He wanted to make the army smaller and better organized. In August 1925, he became a lieutenant-colonel. He tried to reduce the military's size, but his ideas were not always popular.

Yamashita was part of a group in the military called the "Imperial Way" faction. This group had different ideas from another group called the "Control Faction," led by Hideki Tojo. In 1927, Yamashita worked in Vienna, Austria, as a military helper until 1930. He was then promoted to colonel. In 1930, he took command of the 3rd Imperial Infantry Regiment. He became a major-general in August 1934.

After an attempted coup in 1936, Yamashita asked for leniency for the rebel officers. This made Emperor Hirohito unhappy with him. Yamashita thought about leaving the army, but his superiors convinced him to stay. He was then sent to a less important post in Korea. Some say this time helped him reflect and study Zen Buddhism, which made him calmer.

In November 1937, Yamashita became a lieutenant-general. He believed Japan should end its conflict with China and have peaceful relations with the United States and Great Britain. However, his advice was not followed. He was then given a less important role in the Kwantung Army.

From 1938 to 1940, he commanded the IJA 4th Division in northern China. In December 1940, Yamashita went on a secret military trip to Germany and Italy. He met with Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. Yamashita always pushed for his ideas, like making the air force stronger and making the army more modern. These ideas often caused disagreements between him and General Hideki Tojo, who was the war minister.

World War II

Malaya and Singapore Campaigns

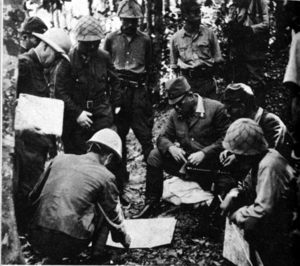

On November 6, 1941, Lieutenant General Yamashita was put in charge of the Twenty-Fifth Army. He believed that to win in Malaya, his troops needed a good landing spot from the sea, with strong air and naval support.

On December 8, he launched an invasion of Malaya. Yamashita knew his forces were much smaller than the British forces. So, he planned to conquer Malaya and Singapore very quickly. This would help overcome the numbers disadvantage and avoid a long, costly battle.

The Malayan campaign ended with the fall of Singapore on February 15, 1942. Yamashita's 30,000 soldiers captured 80,000 British, Indian, and Australian troops. This was the largest surrender of British-led forces in history. This victory earned him the nickname "Tiger of Malaya."

During this campaign and the later Japanese occupation of Singapore, terrible actions were committed against Allied soldiers and civilians. These included massacres at places like the Alexandra Hospital. There is debate about how much Yamashita was responsible for these events. Some argue he failed to stop them. Yamashita later apologized to the few survivors of the Alexandra Hospital massacre. He also reportedly had some soldiers executed for looting after the slaughter.

Some historians argue that Yamashita was a good leader and tactician. However, his personal beliefs often clashed with the military's General Staff. He treated prisoners of war and British leaders humanely, which other officers found difficult to accept. While he was blamed for some massacres, some studies suggest he had no direct part in them. Instead, his subordinates were behind these incidents.

Manchukuo Assignment

On July 17, 1942, Yamashita was moved from Singapore to Manchukuo, a far-off region. He was given command of the First Area Army. This effectively kept him out of the main fighting for a large part of the Pacific War. Many believe that Hideki Tojo, who was then the Prime Minister, was responsible for this. Tojo may have been upset by a speech Yamashita gave in Singapore. In that speech, Yamashita called the local people "citizens of the Empire of Japan." This was embarrassing for the Japanese government, as they did not officially give occupied people the same rights as Japanese citizens. Yamashita was promoted to full general in February 1943.

Philippines Campaign

On September 26, 1944, the war was going badly for Japan. Yamashita was called back from his distant post by the new Japanese government. He took command of the Fourteenth Area Army to defend the occupied Philippines. Ten days later, U.S. forces landed on Leyte. On January 6, 1945, the Sixth U.S. Army, with 200,000 soldiers, landed in Luzon.

Yamashita commanded about 262,000 troops. He tried to rebuild his army but was forced to retreat from Manila. He moved his forces into the mountains of northern Luzon. Yamashita ordered most of his troops out of Manila. He did not declare Manila an open city. An "open city" means a city will not be defended in battle to protect civilians and buildings. Because Yamashita did not do this, Japanese Navy Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi re-occupied Manila with 16,000 sailors. Against Yamashita's specific orders, Iwabuchi turned the city into a battlefield. The fighting and terrible actions by Japanese forces led to the deaths of over 100,000 Filipino civilians. This event is known as the Manila massacre.

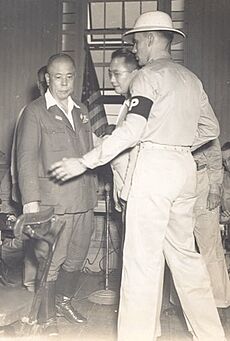

Yamashita continued to fight in the mountains until September 2, 1945. This was the day Japan formally surrendered to General Douglas MacArthur. By the time he surrendered, Yamashita's forces had been reduced to fewer than 50,000 soldiers. This was due to a lack of supplies and tough fighting by American and Filipino soldiers, including guerrillas.

His Trial

From October 29 to December 7, 1945, an American military tribunal (a special court) in Manila tried General Yamashita. He was charged with war crimes related to the Manila massacre and other terrible actions against civilians and prisoners of war in the Philippines. The court sentenced him to death.

Yamashita was held responsible for many war crimes. These included the killing of U.S. prisoners of war and the execution of civilians without proper trials. The prosecution argued that Yamashita was in overall command of the Japanese Army's secret military police, the Kempeitai. This group committed many war crimes. It was argued that Yamashita allowed these actions to happen.

Yamashita said he did not know about the crimes committed by his men. He claimed he would have punished them harshly if he had known. He also argued that with such a large army, it was impossible for him to control every action of all his soldiers.

The court found Yamashita guilty and sentenced him to death. His lawyers appealed the decision, but it was upheld by General MacArthur and later by the U.S. Supreme Court. President Truman also refused to stop the execution.

Some people questioned if the trial was fair. Justice Frank Murphy of the Supreme Court, for example, pointed out problems with the trial process. He mentioned that some evidence was based on rumors and that the trial was not always professional. Evidence that Yamashita might not have had full control over all military units in the Philippines was not allowed in court.

Former war crimes prosecutor Allan A. Ryan has stated that Yamashita was executed for what his soldiers did, even without his approval or knowledge. Two Supreme Court Justices who disagreed with the verdict called the trial a denial of human rights.

Execution

After the Supreme Court's decision, an appeal was made to U.S. President Harry S. Truman to spare Yamashita's life. However, President Truman decided not to interfere. General MacArthur then confirmed the sentence.

On February 23, 1946, Yamashita was hanged at Los Baños, Laguna Prison Camp, about 30 miles (48 km) south of Manila. His remains were later moved to Tama Cemetery in Fuchū, Tokyo, Japan. On December 23, 1948, Akira Mutō, who was Yamashita's chief of staff in the Philippines, was also executed after being found guilty of war crimes.

Lasting Legal Impact

The U.S. Supreme Court's decision in the Yamashita case in 1946 created an important legal rule. This rule is called command responsibility or the Yamashita standard. It means that a military commander can be held legally responsible for crimes committed by their troops. This can be true even if the commander did not order the crimes, did not allow them to happen, or perhaps did not even know about them or have a way to stop them. This idea of a commander's responsibility has since been added to the Geneva Conventions. It has also been used in many trials by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and the International Criminal Court, which was created in 2002.

See also

- Yamashita's gold