Nobusuke Kishi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nobusuke Kishi

|

|

|---|---|

|

岸 信介

|

|

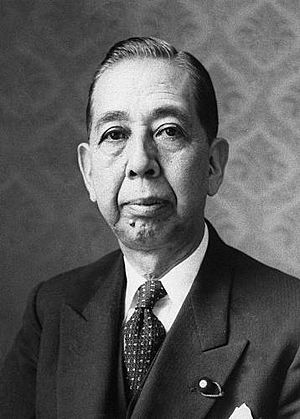

Official portrait, 1957

|

|

| Prime Minister of Japan | |

| In office 31 January 1957 – 19 July 1960 |

|

| Monarch | Hirohito |

| Deputy | Mitsujirō Ishii Shūji Masutani |

| Preceded by | Tanzan Ishibashi |

| Succeeded by | Hayato Ikeda |

| Director-General of the Japan Defense Agency | |

| In office 31 January 1957 – 2 February 1957 |

|

| Prime Minister | Tanzan Ishibashi |

| Preceded by | Tanzan Ishibashi |

| Succeeded by | Akira Kodaki |

| Minister for Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 23 December 1956 – 10 July 1957 |

|

| Prime Minister | Tanzan Ishibashi Himself |

| Preceded by | Mamoru Shigemitsu |

| Succeeded by | Aiichirō Fujiyama |

| Minister of State without Portfolio | |

| In office 8 October 1943 – 22 July 1944 |

|

| Prime Minister | Hideki Tōjō |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Minister of Commerce and Industry | |

| In office 18 October 1941 – 8 October 1943 |

|

| Prime Minister | Hideki Tōjō |

| Preceded by | Seizō Sakonji |

| Succeeded by | Hideki Tōjō |

| Member of the House of Representatives for Yamaguchi 1st District |

|

| In office 1 May 1942 – 8 October 1943 |

|

| In office 20 April 1953 – 7 September 1979 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 November 1896 Tabuse, Yamaguchi Prefecture, Empire of Japan |

| Died | 7 August 1987 (aged 90) Tokyo, Japan |

| Political party | Liberal Democratic Party (1955–1987) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouse |

Yoshiko Kishi

(m. 1919; died 1980) |

| Children |

|

| Parents | Hidesuke Satō Moyo Satō |

| Relatives | Ichirō Satō (brother) Eisaku Satō (brother) Hironobu Abe (grandson) Shinzo Abe (grandson) Nobuo Kishi (grandson) |

| Alma mater | Tokyo Imperial University |

| Signature |  |

Nobusuke Kishi (born Nobusuke Satō, 13 November 1896 – 7 August 1987) was an important Japanese politician. He served as the Prime Minister of Japan from 1957 to 1960.

Kishi was known for his role in managing the economy of Manchukuo, a state in Northeast China that was controlled by Japan in the 1930s. Because of his strong leadership style, he was sometimes called the "Monster of the Shōwa era." During World War II, Kishi was a minister in the government of Prime Minister Hideki Tōjō. He even signed the declaration of war against the United States in 1941.

After the war, Kishi was held in prison for three years because he was suspected of being a war criminal. However, the U.S. government decided not to charge or try him. They believed Kishi was the best person to help lead Japan in a pro-American direction after the war. With support from the U.S., he helped unite conservative political groups in Japan. He played a key role in forming the powerful Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in 1955. This party became very dominant in Japanese politics for a long time.

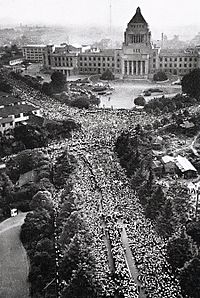

As prime minister, Kishi tried to change the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty in 1960. This led to huge protests, the biggest in Japan's modern history. These protests forced him to resign from his position.

Nobusuke Kishi's younger brother, Eisaku Satō, also became a prime minister. Kishi was also the grandfather of Shinzo Abe, who served as prime minister twice, and Nobuo Kishi, who became a defense minister.

Contents

Early Life and Career

Kishi was born Nobusuke Satō in Tabuse, Yamaguchi Prefecture. His family had a history as samurai but had faced tough times. His older brother, Ichirō Satō, became a Vice Admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy. His younger brother, Eisaku Satō, later became a prime minister.

Nobusuke went to elementary and middle school in Okayama and Yamaguchi. Before finishing middle school, he was adopted by his father's older brother, Nobumasa Kishi. He took their family name to continue their family line, as they had no male heir.

Kishi passed a very difficult exam to enter First High School in Tokyo, which was the most respected high school in Japan. He then went to Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo). He graduated from the law school in 1920 with the highest grades in the university's history. At the university, Kishi was mentored by Shinkichi Uesugi, a legal scholar. Kishi's studies led him to favor a strong government role in the economy.

After graduating, Kishi joined the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. This was an unusual choice for top students, who usually aimed for administrative roles. However, Kishi wanted to be directly involved in Japan's economic growth.

From 1926 to 1927, Kishi traveled the world to study industry and economic policies. He visited countries like the United States, Germany, and the Soviet Union. He was very impressed by the Soviet Union's Five-Year Plan, which focused on economic planning. He also liked American ideas about managing workers and German industrial policies. Kishi became known as a "reform bureaucrat" who believed the state should guide and direct the economy.

Economic Manager of Manchukuo

In 1931, the Japanese Kwantung Army took control of Manchuria in China. They created a puppet state called "Manchukuo." Even though Puyi, the last emperor of China, was the official ruler, Japan truly controlled Manchukuo. Japanese officials held all the real power. The Japanese Army wanted to make Manchukuo an industrial center to support the Japanese Empire. They focused on heavy industries like steel production for military use.

Kishi is often called the "mastermind" behind Manchukuo's industrial growth. He was seen as a rising star in the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. He supported ideas similar to those in Nazi Germany, which called for the state to guide the economy. In 1935, Kishi was made Deputy Minister of Industrial Development for Manchukuo. He was given full control over Manchukuo's economy, with the goal of increasing industrial output.

In 1936, Kishi helped create Manchukuo's first Five-Year Plan. This plan was inspired by the Soviet Union's economic plans. It aimed to greatly increase the production of coal, steel, electricity, and weapons for military purposes. Kishi convinced the military to allow private companies to invest in Manchukuo. He argued that state-owned companies were costing too much money.

One new company created for the Five-Year Plan was the Manchurian Industrial Development Company (MIDC) in 1937. It attracted a huge amount of private investment. Kishi chose Ayukawa Yoshisuke, the founder of Nissan Group, to lead the MIDC. The Nissan Group's operations were moved to Manchuria to form the basis of this new company. The economic system Kishi created in Manchuria, where the government guided investments, later became a model for Japan's economic development after 1945. It also influenced South Korea and China.

To make it profitable for large Japanese companies (zaibatsu) to invest, Kishi kept workers' wages very low. Manchukuo's purpose was to support Japan's military. Historian Mark Driscoll noted that Kishi's plan focused on production and profit, not competition. Profits came from keeping labor costs as low as possible. This included using forced labor. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese people were forced to work in Manchukuo's heavy industries. In 1937, Kishi signed a decree allowing the use of forced labor in Manchukuo and northern China. He stated that during wartime, industry needed to grow at any cost, ensuring profits for investors. From 1938 to 1944, about 1.5 million Chinese people were forced to work as laborers in Manchukuo each year. Conditions were very harsh. For example, at the Fushun coal mine, about 25,000 out of 40,000 miners had to be replaced every year because they died from poor working and living conditions.

Kishi did not seem to care much about following laws in Manchukuo. He often spoke negatively about the Chinese people, calling them "lawless" and "incapable of governing themselves." His staff said he believed the Chinese would only understand force, not legal procedures. Kishi always referred to Manchukuo as "Manshū," meaning just a region, not a real state. This showed his view that it was simply a resource-rich area for Japan's benefit.

Minister in Wartime Governments

In 1939, Kishi became Vice Minister of Commerce in Prince Fumimaro Konoe's government. Kishi wanted to create a similar "national defense state" in Japan as he had in Manchuria. However, large Japanese companies strongly opposed his plans, calling him a communist. Kishi was fired in December 1940.

Less than a year later, in October 1941, Kishi joined the cabinet as Minister of Commerce under the new prime minister, Hideki Tōjō. Kishi and General Tōjō had worked closely in Manchuria, and Tōjō saw Kishi as his protégé.

On 1 December 1941, Kishi voted with the cabinet for war against the United States and Britain. He also co-signed the declaration of war issued on 7 December 1941. In April 1942, Kishi was elected to the Lower House of the Japanese Diet. His connections in the business world and his organizational skills helped Japan's war efforts.

In 1943, the Ministry of Commerce was replaced by the new Ministry of Munitions. Kishi was demoted to Vice Minister of Munitions. Tōjō wanted to hold more power himself, serving as Prime Minister, Minister of War, and Minister of Munitions. This demotion strained Kishi's relationship with Tōjō.

Kishi became increasingly convinced that Japan could not win the war. He believed Japan should seek peace with the Americans. In July 1944, after Japan's defeat at the Battle of Saipan, Tōjō tried to save his government by changing his cabinet. Kishi refused to resign, telling Tōjō he would only leave if the prime minister and the entire cabinet resigned. Kishi's actions helped bring down the Tōjō government. This led to General Kuniaki Koiso replacing Tōjō as prime minister.

In March 1945, Kishi started a new political party called the National Salvation Society. This party opposed the Imperial Rule Assistance Association. Kishi brought 32 members of the Diet into his new party. Most of its members were small and medium-sized business owners who had invested in Manchukuo or benefited from state contracts.

Prisoner in Sugamo

After Japan surrendered to the Allies in August 1945, Kishi was held at Sugamo Prison. He was suspected of being a "Class A" war criminal by the Allied powers. Kishi, along with influential friends like Yoshio Kodama and Ryōichi Sasakawa, were imprisoned together. They were never formally charged or tried. Their bond formed in prison lasted throughout their lives.

During this time, a group of influential Americans, called the "American Council on Japan," supported Kishi. They asked the American government to release him. They believed Kishi was the best person to lead Japan in a pro-American direction after the war. Unlike Hideki Tōjō and other cabinet members who were put on trial, Kishi was released in 1948. He was never indicted or tried by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. However, he was legally banned from public life due to the Allied occupation's purge of former regime members.

While in prison, Kishi began planning his return to politics. He thought about creating a large party, a "popular movement of national salvation." This party would unite moderate socialists and conservatives. It would use government-guided economic methods to encourage growth and unite all Japanese citizens behind nationalist policies.

Return to Politics

When the ban on former government members was lifted in 1952, Kishi returned to politics. He was key in forming the "Japan Reconstruction Federation." Kishi's main goal in politics was to change the American-imposed constitution, especially Article 9. He believed that for Japan to be a "respectable member" of the world, it needed to change its constitution and rearm. He argued that if Japan could defend itself, there would be no need for U.S. troops in Japan.

Kishi's Japan Reconstruction Federation did not do well in the 1952 elections, and Kishi failed to be elected. After this defeat, he disbanded his party. He tried to join the Socialists but was rejected. He then reluctantly joined the Liberal Party. After being elected to the Diet as a Liberal in 1953, Kishi worked to undermine the Liberal Party leader, Shigeru Yoshida. Kishi criticized Yoshida for being too close to the Americans and for not changing Article 9. In April 1954, Yoshida expelled Kishi from the party.

Kishi had prepared for this. He had already found over 200 Diet members willing to join him in a new party to challenge Yoshida. Kishi attracted these politicians with money from his powerful business supporters. In November 1954, Kishi co-founded the new Democratic Party with Ichirō Hatoyama. Hatoyama was the party leader, but Kishi was the party secretary and controlled the party's money. This made him very powerful within the Democrats. Elections in Japan were expensive, so candidates needed money from the party to run successful campaigns. Kishi decided which candidates received money, making him very influential.

In February 1955, the Democrats won the general elections. The day after Hatoyama became prime minister, Kishi began talks with the Liberals. He wanted to merge the two parties now that his rival Yoshida had stepped down. In November 1955, the Democratic Party and Liberal Party merged to form the new Liberal Democratic Party. Ichirō Hatoyama became its head. Within the new party, Kishi again became the party secretary, controlling its finances. Kishi assured the American ambassador that Japan would work closely with the United States for the next 25 years. The Americans wanted Kishi to become Prime Minister. They were disappointed when Tanzan Ishibashi, who was less pro-American, won the party's leadership. However, just 65 days later, in February 1957, Ishibashi resigned due to illness. Kishi was then elected to lead his party and the nation as prime minister.

Prime Minister of Japan

Key Goals

In February 1957, Kishi became Prime Minister. His main focus was foreign policy. He especially wanted to revise the 1952 U.S-Japan Security Treaty. He felt this treaty made Japan too dependent on America. Changing the treaty was the first step towards his ultimate goal: getting rid of Article 9 of the constitution. Besides wanting a more independent foreign policy, Kishi aimed to build strong economic ties with countries in South-East Asia. He also wanted the Allies to release remaining war criminals, arguing it would help Japan play its role as a Western ally in the Cold War.

Asian Development Fund

In his first year, Japan joined the United Nations Security Council. It also paid war reparations to Indonesia and signed new treaties with Australia, Czechoslovakia, and Poland. In 1957, Kishi proposed a plan for a Japanese-led Asian Development Fund (ADF). Its slogan was "Economic Development for Asia by Asia." Japan would invest millions of yen in Southeast Asia. With markets in China and North Korea closed due to the Cold War, Japan and the U.S. looked to Southeast Asia for trade and resources. The U.S. wanted more aid to Asia to prevent the spread of Communism. Kishi hoped that Japan spending $500 million in loans and aid would improve his standing with Washington. This would give him more power in talks to revise the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty.

Kishi visited India, Pakistan, Burma, Thailand, Ceylon, and Taiwan in May 1957 to promote the ADF. Only Taiwan agreed to join. Other nations gave unclear answers. In November, Kishi toured Southeast Asia again, visiting South Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Australia, and New Zealand. These countries, many of which Japan had attacked or occupied during World War II, were hesitant. Only Laos, which needed foreign aid, showed interest. Even countries not occupied by Japan, like India, Ceylon, and Pakistan, had concerns. Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru told Kishi that India wanted to be neutral in the Cold War. Joining the ADF would align India with the U.S. The Pakistani Prime Minister preferred direct aid over a multi-country fund.

Overall, bad memories of Japan's wartime actions, suspicion of Japan's motives, and a desire to avoid new colonial relationships contributed to the failure of Kishi's plan. Even the United States was not fully supportive. The project was put aside, though parts of it later inspired the Asian Development Bank.

Treaty Revision Efforts

Kishi's next foreign policy goal was even harder: changing Japan's security relationship with the United States. Kishi always saw the American-created system as temporary. He believed Japan would one day become a great power again. In June 1957, Kishi visited the United States. He was given great honors, including speaking to Congress and throwing the first pitch at a New York Yankees game. Vice President Richard Nixon introduced Kishi to Congress as a "great leader of the free world" and a "loyal friend of the United States."

In November 1957, Kishi proposed changes to the US–Japan Mutual Security Treaty. The Eisenhower administration finally agreed to negotiations. The American ambassador, Douglas MacArthur II, reported to Washington that Kishi was the most pro-American Japanese politician. He warned that if the U.S. refused to revise the treaty, a less friendly leader might replace Kishi. U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles wrote that the U.S. had to "make a Big Bet" on Japan, and Kishi was their "only bet." Kishi also used growing anti-U.S. military base sentiment in Japan to suggest that if the treaty wasn't revised, U.S. bases might become unwelcome.

Kishi expected public opposition to his treaty plans. He proposed a strict "Police Duties Bill" to the Diet. This bill would give police much more power to stop protests and search homes without warrants. In response, a national group of left-leaning organizations, led by the Japan Socialist Party, launched protests in late 1958. These protests successfully angered the public, and Kishi was forced to withdraw the bill.

The 1960 Anpo Protests

In late 1959, Kishi made it clear he wanted to stay prime minister for more than two terms, breaking tradition. He hoped that successfully revising the Security Treaty would give him enough political power to do this. His opponents within his own Liberal Democratic Party, who felt it was their turn for power, vowed to end his time as prime minister. Meanwhile, negotiations for the new treaty finished in 1959. In January 1960, Kishi went to Washington, D.C., and signed the new treaty with President Eisenhower on January 19. During his visit, Kishi appeared on the cover of Time magazine, which praised Japan's recovery.

Even though the new treaty improved Japan's position and made the U.S.-Japan alliance more equal, many Japanese people disliked having any security treaty with the U.S. They worried it would involve Japan in another war. In 1959, the group that defeated Kishi's Police Duties Bill started protesting the revised Security Treaty. Radical student activists from the Zengakuren student group and labor union members invaded the National Diet building in November 1959. In January, Zengakuren activists tried to stop Kishi from flying to Washington by holding a sit-in at Tokyo's Haneda Airport, but police cleared them away.

Kishi expected the new treaty to be approved quickly. He invited President Eisenhower to visit Japan starting on June 19, 1960, to celebrate the treaty. If the visit happened, Eisenhower would be the first U.S. president to visit Japan while in office. However, when the Diet began debating the treaty, the opposition Japan Socialist Party and Kishi's rivals used tactics to delay the vote. They hoped to prevent approval before Eisenhower's visit and give protesters more time.

As Eisenhower's visit approached, Kishi became desperate to ratify the treaty. On May 19, 1960, Kishi suddenly called for a quick vote. When Socialist Diet members tried to block the vote, Kishi brought 500 police officers into the Diet. They physically removed his political opponents. Kishi then passed the revised treaty with only members of his own party present. Kishi's actions during this "May 19 Incident" angered many people. Even conservative newspapers called for his resignation. After this, the anti-treaty protests grew much larger. Labor unions held nationwide strikes, and large crowds gathered around the National Diet almost daily.

On June 10, White House Press Secretary James Hagerty arrived in Tokyo to prepare for Eisenhower's visit. Hagerty was picked up by U.S. Ambassador to Japan Douglas MacArthur II. MacArthur intentionally drove the car into a large crowd of protesters. He believed it was better to see if the demonstrators would use violence before the President arrived. In the "Hagerty Incident", protesters surrounded the car, rocking it for over an hour. They chanted anti-American slogans. MacArthur and Hagerty had to be rescued by a US Marines military helicopter.

On 15 June 1960, Zengakuren student activists tried to storm the Diet building again. This led to a fierce fight with police, and a female Tokyo University student named Michiko Kanba was killed. Kanba's death caused the largest protests in Japanese history, against both police brutality and the treaty. By this point, Kishi was so unpopular that all LDP groups demanded his resignation. In April 1960, South Korean president Syngman Rhee had been overthrown by student protests. There were fears in Japan that similar protests might lead to a revolution, making it urgent to remove Kishi.

Kishi wanted to stay in office long enough to host Eisenhower's visit. He hoped to clear the streets by calling out the Japan Self Defense Forces and thousands of right-wing supporters provided by his friend, Yoshio Kodama. However, his cabinet convinced him not to take these extreme steps. He then had no choice but to cancel Eisenhower's visit. On June 16, he announced he would resign within a month, taking responsibility for the chaos.

Despite Kishi's announcement, the anti-treaty protests grew even larger. The biggest protest of the entire movement happened on June 18. However, on June 19, the revised Security Treaty automatically took effect under Japanese law, 30 days after passing the lower house. On July 15, 1960, Kishi officially resigned. Hayato Ikeda became prime minister. Ikeda soon made it clear that the LDP would not try to revise Article 9 of the Constitution for a long time. From Kishi's point of view, this meant his efforts had been in vain.

Later Years

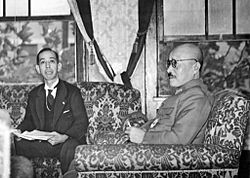

After taking power in a coup d'état in May 1961, South Korean dictator General Park Chung Hee visited Japan in November 1961. He discussed establishing diplomatic relations between Japan and South Korea, which happened in 1965. Park had been a Japanese military officer in the Manchukuo Army. During his visit to Japan, Park met with Kishi. Speaking fluent Japanese, Park praised Japan's "efficiency" and said he wanted to learn "good plans" for South Korea. Park was very interested in Kishi's economic policies in Manchuria as a model for South Korea. Kishi told the Japanese press he was "a little embarrassed" by Park's words, which sounded like wartime Japanese officers. During his time as president of South Korea, Park launched Five-Year Plans for economic development. These plans used government-guided economic policies very similar to the Five-Year Plan Kishi had managed in Manchukuo.

For the rest of his life, Kishi remained dedicated to changing the Japanese Constitution to remove Article 9 and rearm Japan. In 1965, Kishi gave a speech calling for Japanese rearmament. He saw it as a way to fully overcome the effects of Japan's defeat and the American occupation. He believed it would help Japan move past the post-war era and regain its pride. In his later years, Kishi became frustrated that constitutional revision had not happened. In his memoirs, he wrote that the idea of changing the constitution was always on his mind. He blamed Hayato Ikeda and his brother, Eisaku Satō, for ensuring the constitution remained unchanged while they were in power.

Kishi remained in the Diet until he retired from politics in 1979. Even after retiring, he remained a strong influence behind the scenes in LDP politics. After several months of illness, Kishi died on August 7, 1987, at the age of 90.

Personal Life and Descendants

In 1919, Kishi married his cousin Yoshiko Kishi. He was then adopted by her parents. Their son Nobukazu was born in 1921, and their daughter Yōko was born in 1928.

Kishi's daughter Yōko Kishi married politician Shintarō Abe. Their second son, Shinzō Abe, served as prime minister of Japan from 2006 to 2007 and again from 2012 to 2020. Their third son, Nobuo Kishi, was adopted by Kishi's son Nobukazu shortly after birth. Nobuo lived with Kishi in his later years. He won Kishi's historical Diet seat in 2012 and became Minister of Defense in 2020.

Honors

- Coronation Medal (10 November 1928)

- Order of the Sacred Treasure, 5th Class (April 1934)

- Military Medal of Honor (April 1934)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers (29 April 1967)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (7 August 1987; posthumous)

Foreign Honors

Mexico: Sash of the Order of the Aztec Eagle (5 August 1959)

Mexico: Sash of the Order of the Aztec Eagle (5 August 1959) West Germany: Grand Cross 1st Class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (1960)

West Germany: Grand Cross 1st Class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (1960) Republic of China: Grand Cordon of the Order of Propitious Clouds (19 November 1969)

Republic of China: Grand Cordon of the Order of Propitious Clouds (19 November 1969) United Nations: Peace Medal (28 August 1979)

United Nations: Peace Medal (28 August 1979)

See also

In Spanish: Nobusuke Kishi para niños

In Spanish: Nobusuke Kishi para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |