Clinton Engineer Works facts for kids

The Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) was a secret factory built during World War II. It was part of the Manhattan Project, which was a huge effort to create the first atomic bombs. The CEW made the special enriched uranium used in the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima. It also produced the first plutonium from nuclear reactors.

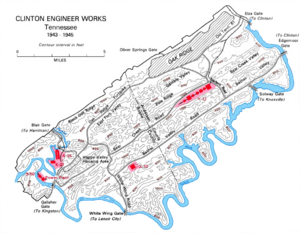

The CEW had three main production areas, a power plant, and a whole town called Oak Ridge. It was located in East Tennessee, about 18 miles (29 km) west of Knoxville. The project was named after the nearby town of Clinton.

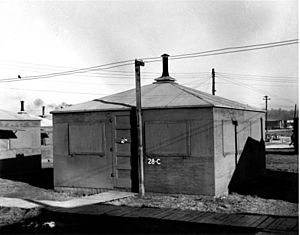

Thousands of construction workers lived in a temporary community called Happy Valley. It was built by the Army Corps of Engineers in 1943 and housed 15,000 people. The town of Oak Ridge was created for the factory workers. At its busiest, after the war, 50,000 people worked there. The construction team peaked at 75,000 workers. The town was also set up with segregated areas; for example, Black residents lived in "hutments" (small shacks) in an area called Gamble Valley.

Contents

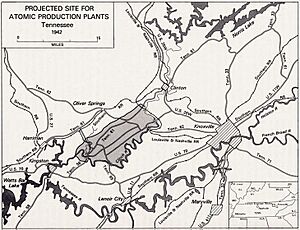

Choosing the Secret Location

In 1942, the Manhattan Project needed a place to build its huge factories for making atomic bombs. The project leaders decided that all the different factories should be built in one place. This would make security and construction easier.

The chosen site needed a lot of land for both the factories and homes for thousands of workers. It also had to be far from other towns, especially the plutonium plant, in case of accidents with radioactive materials. But it also needed to be close to workers and easy to reach by roads and trains. A mild climate was good for year-round building. Hills and valleys would help contain any accidental explosions. The ground needed to be firm for foundations but not too rocky for digging.

The factories would need a huge amount of electricity (150,000 kW) and a lot of water (370,000 US gallons or 1.4 million liters per minute). The War Department also had rules about where military factories could be built, generally avoiding coastal areas or borders.

Many places were considered, including sites in the Tennessee Valley, near Chicago, California, and Washington state (where the Hanford Site was later built). The Knoxville area in Tennessee was chosen in April 1942. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) promised to provide enough electricity.

On July 1, 1942, Army officers and contractors looked at sites near Knoxville. No perfect spot was found. The plans for the different nuclear technologies were still being developed. But they could start building homes and offices. The most promising site was about 12 miles (19 km) west of Knoxville. It was a quiet, rural area with oak and pine-covered ridges around the Clinch River. It was a beautiful countryside with rolling hills.

This site was in Roane County and Anderson County. A main road, Tennessee State Route 61, ran through it, but they planned to reroute it. Buying the 83,000-acre (34,000 ha) site was estimated to cost $4.25 million.

Leslie R. Groves Jr. became the director of the Manhattan Project on September 23. He visited the site and thought it was an excellent choice. He ordered the land to be bought. The site was first called the Kingston Demolition Range. In January 1943, it officially became the Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) and was given the secret name Site X. Later, the town built there was named Oak Ridge. This name sounded rural and helped keep the project secret. Oak Ridge became the site's postal address, but the entire site wasn't officially renamed Oak Ridge until 1947.

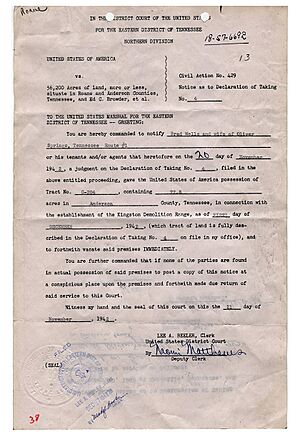

Getting the Land

The War Department usually bought land directly. But because time was short, they decided to use condemnation. This meant the government could take the land quickly, pay the owners, and start building right away. On September 28, 1942, an office opened in Harriman to handle the land purchases.

On September 29, the Under Secretary of War approved buying 56,000 acres (23,000 ha) for about $3.5 million. On October 6, a court order allowed the government to take possession of the land the next day. They tried to be fair to landowners, only taking land needed for immediate construction at first.

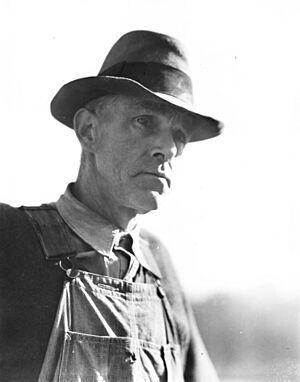

Over 1,000 families lived on the site, on farms or in small villages. Most found out their land was being taken when a government representative visited or an eviction notice was nailed to their door. Many were given only six weeks to leave, some just two. By May 1943, the government had taken 53,334 acres (21,580 ha). Most residents were told to leave between December 1 and January 15. The Army sometimes allowed people to stay longer if it caused too much hardship.

For some, this was not the first time the government had moved them. They had been moved before for the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in the 1920s and the TVA's Norris Dam in the 1930s. Many expected the Army to help them move, like the TVA did. But the Army had no funds for this. It was wartime, so tires and moving vehicles were hard to find. Some people had to leave their belongings behind.

Landowners protested and hired lawyers. Local newspapers and politicians supported them. By May 1943, agreements were reached for many properties, but some landowners rejected the government's offers. The Army tried using a jury to decide fair prices, but landowners still rejected them.

Congressman John Jennings, Jr. from Tennessee complained about the land acquisition. He also said that buildings were being torn down by the Army. A committee investigated in August 1943. Their report made recommendations, but Congress and the War Department did not give more money to the landowners.

In July 1943, General Groves tried to declare the site a military exclusion area. The Governor of Tennessee, Prentice Cooper, was upset because he hadn't been told about the project. He also said the Army had kicked farmers off their land and hadn't paid the counties for roads and bridges that would be closed. He called it "an experiment in socialism." He tore up the proclamation.

Kenneth Nichols, the new chief engineer for the Manhattan District, met with Governor Cooper. Nichols offered money for road improvements. Cooper agreed to visit the CEW. They also made a deal about the Solway Bridge, which was now only used by CEW workers. Knox County received $25,000 a year for the bridge. Anderson County received $10,000 for the Edgemoor Bridge.

More land was bought in 1943 and 1944 for roads, a railway, and security. The total land acquired was about 58,900 acres (23,800 ha). The final cost was around $2.6 million, which was about $47 per acre.

Secret Factories at CEW

X-10 Graphite Reactor: Making Plutonium

On February 2, 1943, DuPont started building a special plant to make plutonium. This was a test plant for much larger factories that would be built later. It included the X-10 Graphite Reactor, which was cooled by air. There was also a chemical plant to separate plutonium, research labs, and other support buildings. This facility was called the Clinton Laboratories. The University of Chicago ran it.

The X-10 Graphite Reactor was the second nuclear reactor ever built. It was the first one designed to run continuously. It was a huge block of graphite cubes, 24 feet (7.3 m) long on each side, weighing about 1,500 short tons (1,400 t). It was surrounded by thick concrete to protect against radiation. It had holes for uranium fuel. Big electric fans cooled the reactor.

Building the reactor was delayed by design issues, wartime material shortages, and a lack of workers. The town of Oak Ridge was still being built, so barracks were set up for workers. Heavy rainfall also caused delays.

Workers started stacking the graphite blocks in September 1943. Uranium fuel came from different suppliers. The reactor started working on November 4, 1943. A week later, it was producing 500 kW of power. By the end of the month, the first 500 milligrams of plutonium were created. The reactor's power was later increased to 4,000 kW.

The chemical plant to separate plutonium was finished on November 26. It started working when the reactor produced irradiated uranium. The first plutonium was made in early 1944. By February, the reactor was irradiating a ton of uranium every three days. The process became more efficient, recovering 90 percent of the plutonium. X-10 made plutonium until January 1945, then it was used for research.

By March 1944, 1,500 people worked at X-10. The total cost for X-10's construction was over $13 million.

Y-12: Separating Uranium with Magnets

The electromagnetic separation method used machines called calutrons. These machines used strong magnetic fields to separate uranium particles based on their weight. Lighter uranium-235 particles would go one way, and heavier uranium-238 particles another. This method wasn't the most efficient, but it was based on proven technology, so it was less risky.

Stone & Webster was in charge of designing and building the electromagnetic separation plant, called Y-12. The plan included five large processing units, called Alpha racetracks, and two smaller units for final processing, called Beta racetracks. Four more Alpha II racetracks were added later. Construction began in February 1943.

When the plant started testing in November, there were problems. The huge 14-ton vacuum tanks moved out of alignment because of the powerful magnets. Also, the magnetic coils started shorting out. Rust was found inside the magnets. General Groves ordered the racetracks to be taken apart and the magnets cleaned. A special plant was set up on-site to clean the pipes. The Alpha I units were working by April 1944. The Alpha II racetracks were finished between July and October 1944.

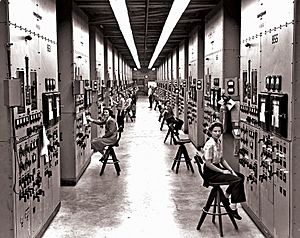

Tennessee Eastman managed Y-12. At first, scientists from Berkeley operated the calutrons. Then, trained operators with only a high school education took over. General Nichols noticed that the young "hillbilly" girl operators were doing better than the PhD scientists. They had a production race, and the girls won! This boosted morale. The girls were "trained like soldiers not to reason why," while the scientists would spend time investigating every small problem.

Y-12 first enriched uranium-235 to 13-15 percent. The first few hundred grams were sent to the Los Alamos Laboratory in March 1944. Only a tiny fraction of the uranium feed became the final product. The rest was splattered on the equipment. By January 1945, they improved recovery to 10 percent. Later, Y-12 started using slightly enriched uranium from other plants, like S-50 and K-25.

The Alpha tracks stopped working in September 1945. By December 1946, most of Y-12 was shut down because the gaseous diffusion plants could do the job alone. Y-12 continued to be used for nuclear weapons work and storing materials.

K-25: Gaseous Diffusion Plant

Gaseous diffusion was a very promising but difficult way to separate isotopes. It uses the idea that lighter gas molecules pass through a special membrane faster than heavier ones. So, if you have a mixture of gases, the gas that comes through the membrane will have more of the lighter molecules. By repeating this process many times, you can get a highly enriched mixture. Scientists at Columbia University worked on this.

In November 1942, the Army approved building a 600-stage gaseous diffusion plant, called K-25. M. W. Kellogg was hired to build it. The project faced huge technical challenges. They had to use a very corrosive gas called uranium hexafluoride. The motors and pumps had to be completely sealed. The biggest problem was designing the "barrier," a special membrane that had to be strong, porous, and resistant to the gas. A new barrier made from powdered nickel was developed.

The K-25 design was a huge U-shaped building, half a mile (0.8 km) long and four stories tall. It had 54 connected buildings, divided into sections. Each section had cells of six stages. Construction began in May 1943. The first pilot plant was ready in April 1944. General Groves later changed the plans, adding a 540-stage unit called K-27. The total cost for K-25 and K-27 was $480 million.

The K-25 plant started working in February 1945. As more sections came online, the quality of the enriched uranium improved. By April, K-25 was enriching uranium to 1.1 percent. By August, all 2,892 stages were working. K-25 and K-27 became very important after the war. Uranium was enriched by the K-25 process until 1985. The plants were then taken apart and cleaned up. A large coal-fired power station was built at K-25 to provide electricity.

S-50: Liquid Thermal Diffusion Plant

Thermal diffusion is another way to separate isotopes. When a mixed gas passes through a temperature difference, the heavier molecules tend to go to the cold end, and the lighter ones go to the warm end. This process was developed by US Navy scientists. It wasn't originally chosen for the Manhattan Project because of doubts about how well it would work.

However, in April 1944, J. Robert Oppenheimer, the director of the Los Alamos lab, heard about good progress in the Navy's experiments. He suggested that a thermal diffusion plant could help Y-12. Groves approved building the S-50 plant on June 24, 1944.

The H. K. Ferguson Company was hired to build S-50. Groves gave them only four months. The plant had 2,142 tall diffusion columns, arranged in 21 racks. Inside each column were three tubes. Hot steam flowed down the inner tube, and cool water flowed up the outer tube. The uranium hexafluoride gas was between the tubes, and the temperature difference helped separate the isotopes.

Work began on July 9, 1944. S-50 started working partially in September. It produced a small amount of enriched uranium in October. Leaks caused problems and shutdowns. But by June 1945, it was producing much more. By March 1945, all 21 production racks were operating.

Initially, S-50's output went to Y-12. But starting in March, all three enrichment processes (S-50, K-25, and Y-12) worked together. S-50 was the first step, enriching uranium from 0.71 percent to 0.89 percent. This was then fed into the K-25 gaseous diffusion plant, which enriched it to about 23 percent. Finally, this went to Y-12 for further enrichment.

After Japan surrendered in August 1945, S-50 was shut down. The plant stopped working by September 9 and was completely torn down in 1946.

Electric Power for the Project

The Manhattan District built a large coal-fired power plant at K-25, even though the TVA said it wasn't needed. This plant had eight 25,000 KW generators. Steam from this plant was also used by S-50. New power lines were added from TVA hydroelectric dams.

By 1945, Oak Ridge could get up to 310,000 KW of power. Most of this was for Y-12 (200,000 KW) and K-25 (80,000 KW). The town itself used 23,000 KW. The peak power use was in August 1945, when all the facilities were running. The steam plant was important for reliability. It was the largest single steam power plant built at one time and was finished very quickly.

Building the Town of Oak Ridge

Planning for a "Government village" to house the workers began in June 1942. Since the site was remote, it was safer and more convenient for workers to live there. The gentle slopes of Black Oak Ridge were chosen for the new town of Oak Ridge. General Groves wanted small, simple houses, but others argued that skilled workers wouldn't live in poor housing. The houses at CEW were basic but better than those at Los Alamos.

The first plan was for a community of 13,000 people. The Army hired Skidmore, Owings & Merrill to design and build the town. This first phase was called the East Town. It included about 3,000 family homes, shopping centers, schools, recreation buildings, dormitories, cafeterias, and a hospital. Speed was important, and they used materials like fiberboard and gypsum board instead of wood. This work was finished in early 1944.

A separate community, the East Village, was built for Black people. But by the time it was finished, white people needed it. Black people were housed in "hutments" (one-room shacks) in segregated areas.

In August 1943, the Army moved its Manhattan District headquarters to Oak Ridge. In September 1943, a company called Roane-Anderson took over running the town's facilities, like laundry, transportation, garbage collection, water, and electricity. At its peak, Roane-Anderson had about 10,500 workers.

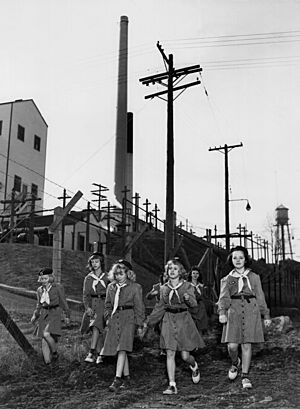

By mid-1943, it was clear the town needed to be much bigger. Plans called for a town of 42,000 people. Construction continued into late 1944. Hospitals were expanded, as were police and fire services. More family houses, dormitories, trailers, and hutments were built. Schools were expanded to hold 7,000 students.

By late 1944, the population was expected to reach 62,000. This led to another round of construction, adding more homes, dorms, shopping, and recreation. Schools were expanded for 9,000 students. The number of school children reached 8,223 in 1945. The quality of education was very important to the scientists. Teachers in Oak Ridge were paid much more than in surrounding areas, which caused some resentment.

The population of Oak Ridge peaked at 75,000 in May 1945. At that time, 82,000 people worked at the Clinton Engineer Works.

Besides the town, there were temporary camps for construction workers. The largest, at Gamble Valley, had four thousand trailers. Another, at Happy Valley, held 15,000 people.

The main shopping area was Jackson Square, with about 20 shops. The Army tried to keep prices low. By 1945, the town had many amenities, including recreation halls, bowling alleys, tennis courts, ball parks, playgrounds, a swimming pool, a library, and a newspaper.

People and Security

From April 1, 1943, access to the Clinton Engineer Works was very strict. There were fences, guarded gates, and patrols. All employees had to sign a security declaration. Mail was censored, and lie detectors were used for security checks. Everyone had a color-coded badge that limited where they could go. Despite this, some atomic spies managed to get secrets to the Soviet Union.

Worker safety was a big concern because people were handling dangerous chemicals, gases, high voltages, and unknown dangers from radioactivity. A strong safety program was put in place. This included safety at home and in schools. Safety training was given, and posters, manuals, and films were used. The Manhattan Project received an award for its safety record.

The people of Oak Ridge were not allowed to have their own local government. However, Tennessee still had control over the land, so residents could vote in state and county elections. There were some disagreements between Oak Ridge residents and the rest of Anderson County. Oak Ridge residents were generally highly educated and demanded excellent schools.

The Army made sure that wages and salaries were high enough to attract and keep good workers. The War Production Board kept stores in Oak Ridge well-stocked. When shortages happened, the well-paid Oak Ridge residents bought scarce goods in nearby areas, which upset local residents.

The War Ends

On May 10, 1945, press kits about the Manhattan Project were prepared for when an atomic bomb was dropped. The last wartime shipment of uranium-235 left the Clinton Engineer Works on July 25. This uranium was used in the Little Boy bomb, which was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6.

News of the bombing was met with huge celebrations in Oak Ridge. The Under Secretary of War, Robert P. Patterson, sent a letter to the workers, thanking them for their secret work. He told them to keep the secrets, as the need for security was still great.

After the War

After the war, Roane-Anderson started handing over many of its tasks. Other companies took over transportation, telephone services, and housing management. In 1946, tenants were allowed to paint their houses in different colors instead of the wartime olive drab. Health care, which had been provided by the Army, was gradually transferred to civilian doctors and private practices.

Monsanto took over the Clinton Laboratories on July 1, 1945. Control of the entire site passed to the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) on January 1, 1947. The Clinton Laboratories became the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in January 1948.

During the war, labor unions were not allowed. But in 1946, they were permitted at the Clinton Engineer Works. Elections were held, and unions became representatives for the workers.

At its peak in May 1945, 82,000 people worked at CEW, and 75,000 lived in the town. By January 1946, these numbers had fallen to 43,000 workers and 48,000 residents. Many construction workers left.

After the war, there was bad publicity about the poor living conditions for Black residents. A new village called Scarboro was built for them, starting in 1948. It housed the entire Black community of Oak Ridge until the early 1960s.

In 1947, Oak Ridge was still like "an island of socialism" because the government ran everything. The AEC wanted to stop running the community, but residents liked the low rents, no property taxes, and excellent services. A survey showed that residents were strongly against opening the gates to the public.

However, on March 19, 1949, the residential and commercial parts of Oak Ridge were officially opened to the public. Important people like Vice President Alben W. Barkley were there to watch the guards take down the barriers. Access to the nuclear facilities was still controlled by three gatehouses. In 1951, the Senate pushed the AEC to stop running the community, encouraging Oak Ridge residents to create their own democratic government.

Images for kids

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |