Soviet atomic bomb project facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Soviet atomic bomb project |

|

|---|---|

| Operational scope | Science and Technology |

| Location | Atomgrad, Semipalatinsk, Chagan |

| Planned by | |

| Date | 1942–1949 |

| Executed by | |

| Outcome |

|

The Soviet atomic bomb project was a top-secret program in the Soviet Union. Its goal was to create nuclear weapons during and after World War II. Joseph Stalin, the Soviet leader, approved this important project.

Even though Soviet scientists talked about an atomic bomb in the 1930s, the full project didn't start until Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941. A Russian physicist named Georgy Flyorov noticed that scientists in other countries had stopped publishing papers on nuclear fission. He suspected they were secretly building a "superweapon." In 1942, Flyorov wrote to Stalin, urging him to start a Soviet bomb program.

At first, the project was slow because of the war. It mostly relied on information gathered by Soviet spies working on the Manhattan Project in the United States. After Stalin learned about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, the Soviet program sped up. They used information from spies and even brought in captured German scientists to help.

On August 29, 1949, the Soviet Union successfully tested its first nuclear weapon. It was called First Lightning and was similar to the American "Fat Man" bomb. This test happened at the Semipalatinsk Test Site in Kazakhstan. A nuclear-armed Soviet Union made its rivals, especially the United States, very worried. From 1949 onwards, the Soviet Union made and tested many nuclear weapons. These tests helped the Soviet Union become a global power. They also made the Cold War with the United States much more serious, leading to the idea of mutually assured destruction, where both sides could destroy each other.

Contents

- Early Discoveries in Nuclear Science

- How the Project Was Organized

- Secret Information and Spies

- Designing Thermonuclear Weapons

- Challenges in Getting Materials

- Key Nuclear Tests

- RDS-1: The First Lightning

- RDS-2: The Second Test

- RDS-3: The Air-Dropped Bomb

- RDS-4: Tactical Weapons Research

- RDS-5: Small Plutonium Device

- RDS-6: The First Hydrogen Bomb Test

- RDS-9: For Nuclear Torpedoes

- RDS-37: The True Hydrogen Bomb

- Tsar Bomba (RDS-220): The Biggest Bomb Ever

- Chagan: Peaceful Nuclear Explosions

- Secret Cities of the Soviet Union

- Impact on Environment and Health

- See also

- Images for kids

Early Discoveries in Nuclear Science

How Russian Scientists Began Studying Atoms

As early as 1910, Russian scientists were already studying radioactive elements. Even with the difficulties of the Russian Revolution in 1917 and the Russian Civil War in 1922, Russian physicists made great progress in physics by the 1930s.

Before the 1905 revolution, a scientist named Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadsky asked for surveys of Russia's uranium deposits, but his requests were not followed. In 1922, the V. G. Khlopin Radium Institute opened in Saint Petersburg. This institute helped make the research more organized and industrial.

From the 1920s to the late 1930s, Russian physicists worked with European scientists to advance atomic physics. Some Russian scientists, like George Gamow and Pyotr Kapitsa, studied at the famous Cavendish Laboratory in England.

Abram Ioffe, who led the Leningrad Physical-Technical Institute (LPTI), guided much of this important research. He supported many research programs across the Soviet Union. When the British physicist James Chadwick discovered the neutron, it opened new possibilities for LPTI's work. Scientists also learned how to "split" the atom's nucleus.

Russian physicists then pushed their government to support science more. Early research focused on radium, which was used in medicine and science. They found radium in water from the Ukhta oilfields.

In 1939, German chemist Otto Hahn discovered nuclear fission. This meant splitting uranium with neutrons to create lighter elements like barium. Russian scientists, like their American counterparts, quickly realized this could have military importance. At first, many were doubtful about making an atomic bomb soon. They focused on using nuclear fission for power.

Yakov Frenkel was one of the first to do calculations on how energy is released during fission in 1940. Georgy Flyorov and Lev Rusinov also found that 3-1 neutrons were released per fission, just days after similar findings by a French team.

World War II and the Push for a Bomb

After strong urging from Russian scientists, the Soviet government created a special group to look into the "uranium problem." This group was supposed to study chain reactions and isotope separation. However, this "Uranium Problem Commission" didn't achieve much. The German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 shifted the country's focus to the war.

During 1940–42, Joseph Stalin, the Soviet leader, didn't pay much attention to the idea of atomic weapons. Most scientists in other fields and military branches also didn't see it as important.

But Georgy Flyorov, a Russian physicist serving in the Soviet Air Force, noticed something strange. German, British, and American scientists had stopped publishing papers on nuclear science. He realized they must have secret research programs.

In April 1942, Flyorov wrote two secret letters to Stalin. He warned Stalin about the huge impact of atomic weapons. He stressed that it was "essential to manufacture a uranium bomb without a delay."

After reading Flyorov's letters, Stalin immediately brought Russian physicists back from their military duties. He approved an atomic bomb project. He put Anatoly Alexandrov and Igor V. Kurchatov in charge. In late 1942, Kurchatov became the technical director of the Soviet bomb program. He was chosen because Abram Ioffe, who was older, recommended him.

A special place called Laboratory No. 2 was set up near Moscow under Kurchatov. Flyorov moved to Dubna to work on synthetic elements. In late 1942, the State Defense Committee put the Soviet Army in charge of the program. Later, Lavrentiy Beria, the head of the NKVD (secret police), oversaw the project's logistics.

In 1945, the Arzamas 16 site was created near Moscow. Scientists like Yakov Borisovich Zel'dovich and Yuli Khariton worked there on nuclear combustion theory. At first, building a bomb with weapon-grade uranium seemed impossible to Russian scientists. But Igor Kurchatov made progress on a bomb using weapon-grade plutonium after the NKVD provided secret information from Britain.

The situation changed dramatically when the Soviet Union learned about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. The Soviet Politburo (the main policy-making committee) immediately took control of the project. They wanted to develop nuclear weapons as fast as possible.

On April 9, 1946, the Council of Ministers created KB–11 ('Design Bureau-11'). This group worked on designing the first nuclear weapon, mostly based on the American design. This bomb would use weapon-grade plutonium.

Work on the program sped up with the building of a nuclear research reactor near Moscow. It started working for the first time on October 25, 1946. Even while this reactor was being planned, the government approved a location east of the Urals for a plutonium production facility. This facility would be like the American Hanford Site. It included a much larger nuclear production reactor and a factory to extract radioactive materials. This complex, built near Kyshtym, became known as Chelyabinsk-40 and later Mayak.

The area was chosen partly because it was close to the Chelyabinsk Tractor Plant, which had become a major tank production center during the war. A huge new power station built in 1942 could supply electricity. Chelyabinsk province, especially around Kyshtym, also had many gulag stations, which were forced labor camps. Tens of thousands of prisoners were used for work in the mines, processing plants, and construction.

How the Project Was Organized

Help from German Scientists

From 1941 to 1946, the Soviet Union's Ministry of Foreign Affairs managed the atomic bomb project. Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov was in charge. However, Molotov wasn't a strong leader, and the program didn't move quickly. Unlike the American Manhattan Project, which was run by the military, the Soviet program was led by political figures like Molotov, Lavrentiy Beria, Georgii Malenkov, and Mikhail Pervukhin. There were no military members involved.

After the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Stalin changed the project's leadership. On August 22, 1945, he appointed Lavrentiy Beria. Beria's strong leadership helped the program succeed.

A scientist named Yulii Khariton said that Beria "understood the necessary scope and dynamics of research." He added that Beria "possessed the great energy and capacity to work." Scientists found him to be a "first-class administrator who could carry a job through to completion."

The new committee under Beria included Georgii Malenkov, Nikolai Voznesensky, and Boris Vannikov. Under Beria, the NKVD used atomic spies from the Soviet Atomic Spy Ring to get information from the American program. They also got information from the German nuclear program. German nuclear scientists later played a key role in helping the Soviets develop their nuclear weapons.

Secret Information and Spies

The Soviet Spy Network

Spies in the United States greatly helped speed up the Soviet nuclear program from 1942 to 1954. These spies were American supporters of communism, controlled by Russian officials in North America. They were more willing to share secret information with the Soviet Union when the USSR faced possible defeat during the German invasion in World War II.

The Russian intelligence network in the United Kingdom also helped set up spy rings in the United States. This happened after the State Defense Committee approved a plan in September 1942. This plan told the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR to restart research on nuclear energy and uranium fission. It also asked for a report on the possibility of a bomb or fuel source by April 1 of the next year.

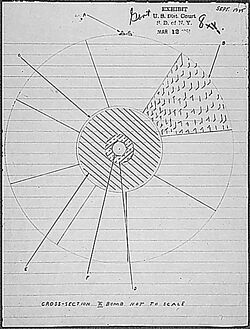

For this mission, a spy named Harry Gold, controlled by Semyon Semyonov, gathered a lot of secret information. This included industrial secrets from the American chemical industry and sensitive atomic information given to him by British physicist Klaus Fuchs. The knowledge and technical details shared by American theoretical physicist Theodore Hall and Klaus Fuchs greatly influenced the direction of Russian nuclear weapon development.

Leonid Kvasnikov, a Russian engineer who became a KGB officer, moved to New York City to manage these spy activities. Anatoli Yatzkov, another NKVD official in New York, also helped get sensitive information.

The existence of these Russian spies was revealed by the U.S. Army's secret Venona project in 1943.

In 1943, Molotov shared the secret intelligence data with Kurchatov. Kurchatov said, "The materials are magnificent. They add exactly what we have been missing." According to historian Richard Rhodes, this information "would accelerate the Soviet program by a full two years." It included a new way to make a bomb without needing to separate uranium isotopes. Instead, Plutonium-239 could be used. This plutonium could be made in a uranium-graphite pile by absorbing neutrons from Uranium-238. Kurchatov also said the spy material made them "include diffusion experiments in our plans along with centrifuge."

Soviet Intelligence and the Manhattan Project

In 1945, Soviet intelligence got rough blueprints of the first U.S. atomic device. Some historians believe that this spying helped the Soviet project by allowing their scientists to avoid dangerous tests. These tests, known as "tickling the dragon's tail," took a lot of time and caused at least two deaths in the U.S.

The Smyth Report of 1945, which was about the Manhattan Project, was translated into Russian. The translators noticed that a sentence about the "poisoning" effect of Plutonium-239 was removed from a later edition of the report. This change alerted the Soviet Union to a problem: reactor-made plutonium couldn't be used in a simple gun-type bomb.

One important piece of information Klaus Fuchs gave to the Soviets was data for D-T fusion. This data was available to top Soviet officials about three years before it was publicly released in 1949. However, this data didn't reach Soviet scientists Vitaly Ginzburg or Andrei Sakharov until much later, just months before it was published. Once they knew the correct data, the "Sloika" (layered cake) bomb design became a priority, leading to a successful test in 1953.

Designing Thermonuclear Weapons

Early ideas for the fusion bomb came from both spying and Soviet research. While spying did help, the first American H-bomb ideas had major flaws. This might have confused the Soviet efforts more than helped them. Early designers thought they could use an atomic bomb as a trigger. This would create the heat and pressure needed to start a fusion reaction in a layer of liquid deuterium. But they realized that without enough heat and compression, the fusion wouldn't work well.

In 1948, Andrei Sakharov's study group came up with a new idea. They suggested adding a shell of natural uranium around the deuterium. This would increase the deuterium concentration and the bomb's overall power. This is because the natural uranium would capture neutrons and also undergo fission as part of the reaction. Sakharov called this layered fission-fusion-fission bomb the "sloika," or "layered cake." It was also known as the RDS-6S, or "Second Idea Bomb." This wasn't a fully developed thermonuclear bomb, but it was a key step between simple fission bombs and the powerful "supers."

Because the U.S. made a key breakthrough in "radiation compression" three years earlier, the Soviet Union's development took a different path. The U.S. decided to skip the single-stage fusion bomb and focus on a two-stage fusion bomb. The Soviets, however, focused on the single-stage 400-kiloton RDS-6S.

The RDS-6S "Layer Cake" bomb was tested on August 12, 1953. The test was code-named "Joe 4" by the Allies. It produced an explosion equal to 400 kilotons of TNT, which was about ten times more powerful than any previous Soviet test. Around this time, the United States tested its first "super" bomb using radiation compression on November 1, 1952, code-named "Mike." Although the Mike bomb was about twenty times more powerful than the RDS-6S, it wasn't practical to use, unlike the RDS-6S.

After the successful RDS-6S test, Sakharov suggested an improved version called RDS-6SD. But this bomb had problems and was never built or tested. The Soviet team also worked on the RDS-6T concept, but it also led to a dead end.

In 1954, Sakharov worked on a third idea: a two-stage thermonuclear bomb. This "third idea" used the radiation wave from a fission bomb to ignite the fusion reaction, not just heat and compression. This was similar to the discovery made by Ulam and Teller in the U.S. Unlike the RDS-6S, which put the fusion fuel inside the first atomic bomb trigger, the new "super" bomb placed the fusion fuel in a separate part. This part was then compressed and ignited by the A-bomb's X-ray radiation. The KB-11 Scientific-Technical Council approved this design on December 24, 1954. The new bomb's details were finished on February 3, 1955, and it was named the RDS-37.

The RDS-37 was successfully tested on November 22, 1955. It had a yield of 1.6 megatons. This was almost a hundred times more powerful than the first Soviet atomic bomb tested six years earlier. This showed that the Soviet Union could compete with the United States in nuclear power.

Challenges in Getting Materials

first air-dropped bomb test in 1951.

This picture is sometimes confused with RDS-27 and RDS-37 tests.

The biggest challenge for the early Soviet program was getting enough raw uranium ore. The Soviet Union had very few uranium sources when their nuclear program began. Domestic uranium mining officially started on November 27, 1942, by order of the powerful wartime State Defense Committee. The first Soviet uranium mine was in Taboshar, Tajikistan. By May 1943, it was producing a few tons of uranium concentrate each year. Taboshar was one of many secret Soviet closed cities linked to uranium mining and production.

However, the experimental bomb project needed much more uranium. The Americans had already secured access to known uranium sources in Congo, South Africa, and Canada with the help of a Belgian businessman in 1940. In December 1944, Stalin took the uranium project away from Vyacheslav Molotov and gave it to Lavrentiy Beria. The first Soviet uranium processing plant was set up as the Leninabad Mining and Chemical Combine in Chkalovsk (now Buston, Ghafurov District), Tajikistan. New production sites were also found nearby.

This created a huge need for workers. Beria filled this need with forced labor. Tens of thousands of Gulag prisoners were brought to work in the mines, processing plants, and construction sites.

Even with these efforts, domestic production wasn't enough. The Soviet F-1 reactor, which started in December 1946, was fueled with uranium taken from the remains of the German atomic bomb project. This uranium had been mined in the Belgian Congo and fell into German hands after their invasion of Belgium in 1940. In 1945, efforts to enrich uranium using the electromagnetic method under Lev Artsimovich also failed. This was because the USSR couldn't build a large facility like the American Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and their power grid couldn't provide enough electricity.

Other sources of uranium in the early years came from mines in East Germany (through SAG Wismut), Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Poland. Boris Pregel also sold 0.23 tons of uranium oxide to the Soviet Union during the war, with U.S. government approval.

Eventually, large uranium sources were discovered within the Soviet Union, including areas now in Kazakhstan.

Here's a table showing uranium production from different countries for the Soviet nuclear weapons program:

| Year | USSR | Germany | Czechoslovakia | Bulgaria | Poland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1945 | 14.6 t | ||||

| 1946 | 50.0 t | 15 t | 18 t | 26.6 t | |

| 1947 | 129.3 t | 150 t | 49.1 t | 7.6 t | 2.3 t |

| 1948 | 182.5 t | 321.2 t | 103.2 t | 18.2 t | 9.3 t |

| 1949 | 278.6 t | 767.8 t | 147.3 t | 30.3 t | 43.3 t |

| 1950 | 416.9 t | 1,224 t | 281.4 t | 70.9 t | 63.6 t |

Key Nuclear Tests

RDS-1: The First Lightning

The RDS-1 was the first Soviet nuclear device. It was tested in Semipalatinsk, Kazakhstan, on August 29, 1949. This first atomic test proved that Russia could build nuclear weapons. It had many internal code-names, including First Lightning (Pervaya Molniya).

However, the test became widely known as "RDS-1" (Rossiya Delayet Sama), which means "Russia Does it Herself." This name was suggested by Igor Kurchatov. All future Russian nuclear tests followed the RDS naming system. The Americans code-named this test Joe 1. Its power and design were mostly based on the American "Fat Man" bomb.

RDS-2: The Second Test

The RDS-2 was the second important nuclear test. It happened on September 24, 1951. Soviet physicists measured its power at 38.3 kilotons. This device was a "boosted" uranium implosion device with a floating core. The U.S. called this test "Joe-2."

RDS-3: The Air-Dropped Bomb

The RDS-3 was the third nuclear explosive device. It was tested on October 18, 1951, also in Semipalatinsk. Known as Joe 3 in America, this was a boosted fission device. It used a mix of a floating plutonium core and a uranium-235 shell. Its estimated blast yield was 41.2 kilotons. The RDS-3 was also special because it was the first Russian bomb dropped from an airplane. It was released from 10 km high and exploded 400 meters above the ground.

RDS-4: Tactical Weapons Research

RDS-4 was part of research into smaller, tactical weapons. It was a boosted fission weapon using plutonium in a "floating" core design. The first test was an air drop on August 23, 1953, with a yield of 28 kilotons. In 1954, this bomb was also used during the Snowball exercise at the Totskoye range. It was dropped by a Tu-4 bomber onto a simulated battlefield, with 40,000 soldiers, tanks, and jet fighters present. The RDS-4 was the warhead for the R-5M, the world's first medium-range ballistic missile. It was tested with a live warhead only once, on February 5, 1956.

RDS-5: Small Plutonium Device

RDS-5 was a small plutonium-based device, likely using a hollow core. Two different versions were made and tested.

RDS-6: The First Hydrogen Bomb Test

RDS-6, the first Soviet test of a hydrogen bomb, took place on August 12, 1953. Americans nicknamed it Joe 4. It used a "layer-cake" design of fission and fusion fuels (uranium 235 and lithium-6 deuteride). It produced a yield of 400 kilotons. This was about ten times more powerful than any previous Soviet test. When developing more powerful bombs, the Soviets focused on the RDS-6 as their main effort. This led to the "third idea" bomb, the RDS-37.

RDS-9: For Nuclear Torpedoes

A much less powerful version of the RDS-4, with a 3-10 kiloton yield, the RDS-9 was made for the T-5 nuclear torpedo. A 3.5 kiloton underwater test was done with the torpedo on September 21, 1955.

RDS-37: The True Hydrogen Bomb

The first Soviet test of a "true" hydrogen bomb in the megaton range happened on November 22, 1955. The Soviets called it RDS-37. It was a multi-staged, radiation implosion thermonuclear design. In the USSR, it was called Sakharov's "Third Idea", and in the U.S., it was the Teller–Ulam design.

The Joe 1, Joe 4, and RDS-37 tests all took place at the Semipalatinsk Test Site in Kazakhstan.

Tsar Bomba (RDS-220): The Biggest Bomb Ever

The Tsar Bomba (Царь-бомба) was the largest and most powerful thermonuclear weapon ever exploded. It was a three-stage hydrogen bomb with a yield of about 50 megatons. This is equal to ten times the power of all the explosives used in World War II combined! It was detonated on October 30, 1961, in the Novaya Zemlya archipelago. It was designed to be about 100 megatons, but its power was purposely reduced just before launch. Even though it was a weapon, it was never used in service. It was simply a demonstration of the Soviet Union's military technology at that time. The heat from the explosion was so intense that it could cause third degree burns from 100 km away in clear air.

Chagan: Peaceful Nuclear Explosions

Chagan was a test in the Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy program (also known as Project 7). This was the Soviet version of the U.S. Operation Plowshare, which explored peaceful uses of nuclear weapons. Chagan was an underground explosion. It happened on January 15, 1965. The site was a dry riverbed of the Chagan River at the edge of the Semipalatinsk Test Site. It was chosen so that the crater's edge would dam the river during its high spring flow. The explosion created a crater 408 meters wide and 100 meters deep. A large lake (10,000 m3) soon formed behind the 20–35 m high raised rim. This lake is known as Chagan Lake or Balapan Lake.

Secret Cities of the Soviet Union

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union created at least nine secret cities. These were called Atomgrads, and they were where nuclear weapons research and development took place. After the Soviet Union broke apart, all these cities changed their names. Most of their original code-names were simply the region (oblast) and a number. All of them are still legally "closed," but some parts can be visited by foreigners with special permits (like Sarov, Snezhinsk, and Zheleznogorsk).

| Cold War name | Current name | Established | Main purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arzamas-16 | Sarov | 1946 | Weapons design and research, warhead assembly |

| Sverdlovsk-44 | Novouralsk | 1946 | Uranium enrichment |

| Chelyabinsk-40 and later 65 | Ozyorsk | 1947 | Plutonium production, making bomb parts |

| Sverdlovsk-45 | Lesnoy | 1947 | Uranium enrichment, warhead assembly |

| Tomsk-7 | Seversk | 1949 | Uranium enrichment, making bomb parts |

| Krasnoyarsk-26 | Zheleznogorsk | 1950 | Plutonium production |

| Zlatoust-36 | Tryokhgorny | 1952 | Warhead assembly |

| Penza-19 | Zarechny (Penza oblast) | 1955 | Warhead assembly |

| Krasnoyarsk-45 | Zelenogorsk | 1956 | Uranium enrichment |

| Chelyabinsk-70 | Snezhinsk | 1957 | Weapons design and research |

Impact on Environment and Health

The Soviets started experimenting with nuclear technology in 1943. They paid very little attention to nuclear safety. No reports of accidents were made public, so people couldn't learn from them. The public was kept unaware of the dangers of radiation. Many of the nuclear devices left behind radioactive materials. These materials contaminated the air, water, and soil in the areas around the blast sites, as well as downwind and downstream.

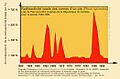

According to records released by the Russian government in 1991, the Soviet Union tested 969 nuclear devices between 1949 and 1990. This was more nuclear testing than any other country. Soviet scientists conducted these tests with little concern for the environment or people's health. The harmful effects of the toxic waste from weapons testing and processing radioactive materials are still felt today. Even decades later, the risk of developing various types of cancer, especially thyroid and lung cancer, is much higher than average for people in affected areas. Iodine-131, a radioactive isotope from fission weapons, stays in the thyroid gland. So, this type of poisoning is common in affected populations.

The Soviets set off 214 nuclear devices in the open atmosphere between 1949 and 1963. This was the year the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty came into effect. The billions of radioactive particles released into the air exposed countless people to very harmful materials. This led to many genetic problems and deformities. Most of these tests happened at the Semipalatinsk Test Site, or the Polygon, in northeast Kazakhstan. The testing at Semipalatinsk alone exposed hundreds of thousands of Kazakh citizens to harmful effects. The site remains one of the most highly radioactive places on Earth.

When the earliest tests were done, even the scientists didn't fully understand the long-term effects of radiation exposure. Many didn't tell each other about serious accidents or radiation exposure. In fact, Semipalatinsk was chosen as the main site for open-air testing because the Soviets wanted to learn about the lasting harm their weapons could cause.

Contamination of air and soil from atmospheric testing is only part of a bigger problem. Water contamination from improperly disposing of spent uranium and decaying sunken nuclear-powered submarines is a major issue in the Kola Peninsula in northwest Russia. The Russian government says the radioactive power cores are stable. However, many scientists are very worried about the 32,000 spent nuclear fuel elements still in the sunken vessels. There haven't been any major incidents other than the explosion and sinking of a nuclear-powered submarine in August 2000. But many international scientists are still concerned that the hulls could erode, releasing uranium into the sea and causing significant contamination.

While the submarines pose an environmental risk, they haven't caused serious harm to public health yet. However, water contamination near the Mayak test site, especially at Lake Karachay, is extreme. Radioactive byproducts have even found their way into drinking water supplies. This has been a concern since the early 1950s, when the Soviets started pumping tens of millions of cubic meters of radioactive waste into the small lake. Half a century later, in the 1990s, there were still hundreds of millions of curies of waste in the lake. At times, the contamination was so severe that just half an hour of exposure to certain areas could deliver enough radiation to kill 50% of humans.

Although the area around the lake has no people, the lake can dry up during droughts. Most importantly, in 1967, it dried up, and winds carried radioactive dust over thousands of square kilometers. This exposed at least 500,000 citizens to many health risks. To control the dust, Soviet scientists piled concrete on top of the lake. This helped reduce the dust, but the weight of the concrete pushed radioactive materials closer to underground groundwater. It's hard to measure the full health and environmental effects of the water contamination at Lake Karachay. This is because figures on civilian exposure are not available. This makes it difficult to directly link higher cancer rates to radioactive pollution specifically from the lake.

Today, efforts to manage radioactive contamination in the former Soviet Union are few. Public awareness of past and present dangers, and the Russian government's investment in cleanup, are likely low. This is because these sites haven't received as much media attention as isolated nuclear incidents like Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Chernobyl, and Three-Mile Island. The Russian government's focus on cleanup seems to be more about money than public health. The most important law in this area allows the already contaminated former weapons complex Mayak to become an international radioactive waste dump. It accepts money from other countries in exchange for taking their radioactive waste from nuclear industries. Although the law says the money should go towards cleaning up other test sites like Semipalatinsk and the Kola Peninsula, experts doubt this will actually happen given Russia's current political and economic situation.

See also

- History of nuclear weapons

- History of the Soviet Union (1927–1953)

- Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

- Military history of the Soviet Union

- Pavel Sudoplatov

- Sino-Soviet split

- Soviet space program

Images for kids

-

The mushroom cloud from the

first air-dropped bomb test in 1951.

This picture is sometimes confused with RDS-27 and RDS-37 tests. -

Former Soviet nuclear devices left behind a lot of radioactive materials. These materials contaminated the air, water, and soil in nearby areas. This even doubled the normal amount of 14C in the atmosphere.

-

This map shows the level of Cesium-137 contamination over Ukraine in 1996. This was after an unsafe operation led to the serious accident in 1986.

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |