Vyacheslav Molotov facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Vyacheslav Molotov

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Вячеслав Молотов

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

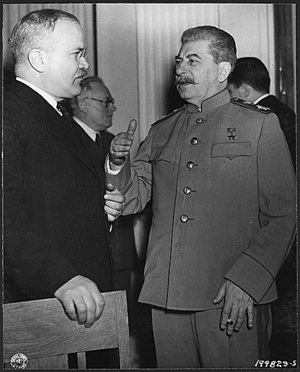

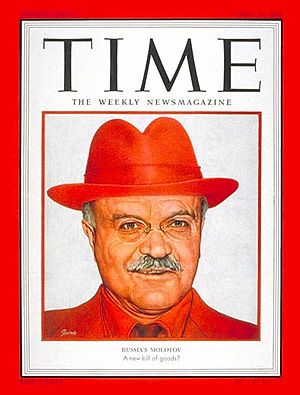

Molotov in 1945

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier of the Soviet Union | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 19 December 1930 – 6 May 1941 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Alexei Rykov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Joseph Stalin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 16 August 1942 – 29 June 1957 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Nikolai Voznesensky | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Nikolai Bulganin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 3 May 1939 – 4 March 1949 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Joseph Stalin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Maxim Litvinov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Andrey Vyshinsky | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 5 March 1953 – 1 June 1956 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Andrey Vyshinsky | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Dmitri Shepilov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Skryabin

9 March 1890 Kukarka, Russian Empire (present day Sovetsk, Kirov Oblast, Russia) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 8 November 1986 (aged 96) Moscow, RSFSR, USSR |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Citizenship | Soviet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Russian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Polina Zhemchuzhina

(m. 1920; died 1970) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Vyacheslav Nikonov (grandson) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Awards | Order of the Badge of Honour | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

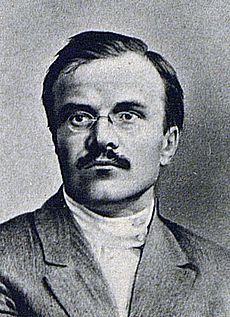

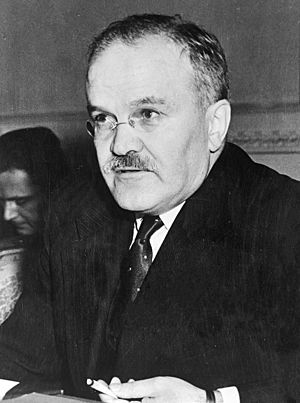

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov (born Skryabin; 9 March 1890 – 8 November 1986) was a very important Russian and later Soviet politician. He was a key leader in the Soviet government for many years. He served as the Premier of the Soviet Union (like a prime minister) from 1930 to 1941. He was also the Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1939 to 1949 and again from 1953 to 1956.

In the 1930s, Molotov was the second most powerful person in the Soviet Union, right after Joseph Stalin. He was very loyal to Stalin for over 30 years. He even continued to defend Stalin's actions after Stalin passed away. In August 1939, Molotov signed a famous agreement with Germany called the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. This was a non-aggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union.

Molotov remained a top Soviet diplomat until March 1949. At that time, he lost favor with Stalin and was replaced as Foreign Minister. After Stalin's death in 1953, Molotov became Foreign Minister again. However, he strongly disagreed with Nikita Khrushchev's plan to move away from Stalin's policies. This disagreement led to Molotov being removed from all his jobs and kicked out of the Communist Party in 1961. He was allowed back into the party in 1984. Molotov continued to defend Stalin's policies until he died in 1986.

The famous homemade firebomb, the Molotov cocktail, is named after him.

Contents

Early Life and Political Start

Vyacheslav Molotov was born Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Skryabin in a village called Kukarka in 1890. His father was a merchant. It's a common mistake, but he was not related to the famous composer Alexander Scriabin.

As a teenager, people described him as "shy" and "quiet." He often helped his father with his business. He went to school in Kazan, where he met a friend who was also a revolutionary, Aleksandr Arosev. In 1906, Molotov joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). He soon became part of the radical group within it called the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin.

Skryabin chose the new name "Molotov." This name came from the Russian word molot, which means "sledge hammer." He thought it sounded "industrial" and "proletarian." He was arrested in 1909 and spent two years exiled in Vologda.

In 1911, he started studying at the St. Petersburg Polytechnic Institute. Molotov joined the team that wrote for a secret Bolshevik newspaper called Pravda. This is where he first met Joseph Stalin. Their first meeting was short and didn't lead to a close friendship right away.

Molotov worked as a "professional revolutionary" for several years. He wrote for the party's newspapers and tried to make the secret party organization better. In 1914, when World War I started, he moved from St. Petersburg to Moscow. The next year, he was arrested again for his party work and sent to Irkutsk in eastern Siberia. In 1916, he escaped from Siberia and returned to the capital city, which was now called Petrograd.

In 1916, Molotov became a member of the Bolshevik Party's committee in Petrograd. During the February Revolution in 1917, he was one of the few important Bolsheviks in the capital. He directed the newspaper Pravda to oppose the new government formed after the revolution. When Stalin returned to the capital, he changed Molotov's direction. But then Lenin arrived and changed it back. Molotov became a close follower of Stalin, which helped him become very important later on. Molotov joined the Military Revolutionary Committee, which planned the October Revolution and helped the Bolsheviks take power.

In 1918, Molotov went to Ukraine during the Russian Civil War. He was not a military person, so he didn't fight. In 1919, he traveled on a steamboat along the Volga River and Kama rivers with Lenin's wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya. They were spreading Bolshevik ideas. When he returned, he became the head of the Nizhny Novgorod provincial executive. However, the local party criticized him for being too sneaky. He was then moved to Donetsk. In November 1920, he became secretary of the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Bolshevik Party and married the politician Polina Zhemchuzhina.

In 1921, Lenin called Molotov back to Moscow. He made him a full member of the Central Committee and the Orgburo. He also put him in charge of the party's main office. Molotov became a non-voting member of the Politburo in 1921. He also held the job of Responsible Secretary. A communist official named Alexander Barmine visited Molotov's office. He remembered Molotov as having "a large and calm face, like an ordinary, kind office worker, who paid attention and was humble."

Lenin and Leon Trotsky criticized Molotov. Lenin said he had "shameful bureaucracy" and "stupid behavior." In 1922, Stalin became the General Secretary of the Bolshevik Party. Molotov became the de facto Second Secretary. Molotov admired Stalin but still criticized him sometimes. With Stalin's support, Molotov became a full member of the Politburo in January 1926.

After Lenin's death in 1924, there were power struggles. Molotov remained a loyal supporter of Stalin against his rivals. These rivals included Leon Trotsky, then Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev, and finally Nikolai Bukharin. In January 1926, Molotov led a special group sent to Leningrad to stop Zinoviev from controlling the party there. In 1928, Molotov took over from Nikolai Uglanov as the First Secretary of the Moscow Communist Party. He held this job until August 15, 1929.

Molotov's Personality

Many people, including Trotsky, didn't think much of Molotov. Trotsky even called him "mediocrity personified," meaning he seemed very ordinary. However, this calm outside hid a very smart mind and great skills in managing things. He mostly worked behind the scenes and tried to appear like a plain office worker.

An American journalist, John Gunther, said in 1938 that Molotov was a vegetarian. But another politician, Milovan Djilas, said Molotov didn't mention being a vegetarian, even though they ate together many times.

Molotov and his wife had two daughters. Sonia was adopted in 1929, and Svetlana was born in 1930.

Leading the Soviet Government

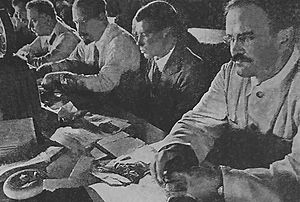

On February 23, 1929, Molotov spoke at a meeting in Moscow. He said that Soviet industry needed to grow as fast as possible. He believed this was important for the economy and because the Soviet Union was always in danger of attack. There was a disagreement between Stalin and other leaders like Bukharin and Rykov about how fast industry should grow. They worried that growing too fast would cause problems. After Stalin won this argument, Molotov became the second most powerful person in the Soviet Union. On December 19, 1930, Molotov took over from Alexey Rykov as the Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars. This job was like being the head of government in Western countries.

In this role, Molotov was in charge of the First Five-Year Plan. This plan aimed to quickly industrialize the Soviet Union. Even though it was very difficult for many people, the Soviet Union made big progress in using new farming and factory technology under Molotov's leadership. Germany secretly bought weapons from the USSR, which helped the Soviet Union build a modern weapons industry. This industry, along with help from America and Britain, later helped the Soviet Union win in World War II.

Farming Changes and Hardships

Molotov also oversaw the forced collectivization of agriculture under Stalin's regime. He was the main speaker at a meeting in November 1929. At this meeting, the decision was made to replace thousands of small farms owned by peasants with large collective farms. This change was expected to face resistance. Molotov insisted it must start the next year. He warned officials to treat the "kulak" (land-owning peasants) as a "cunning and undefeated enemy." Over the next four years, millions of 'kulaks' were forced to move to special settlements to work. In 1931 alone, almost two million people were moved. In that year, Molotov said that using healthy prisoners for road building and other public works was "good for society" and "good for the peasants themselves." The changes in farming and focusing on exporting grain to pay for industry caused a terrible famine. The harsh conditions of forced labor also led to the deaths of an estimated 11 million people.

Despite the famine, Molotov sent a secret message in September 1931. He told communist leaders in the North Caucasus that collecting grain for export was going "disgustingly slowly." In December, he went to Kharkiv, the capital of Ukraine at the time. He ignored warnings about a grain shortage and told local communist leaders that their failure to meet grain collection goals was due to their own mistakes. He returned to Kharkiv in July 1932 with Lazar Kaganovich. They told the local communists that there would be no "concessions or hesitations" in collecting grain for export. This was one of several actions that led a Kyiv Court of Appeal in 2010 to find Molotov and Kaganovich responsible for causing great suffering to the Ukrainian people.

Molotov's Role in the Great Purge

After returning to favor, Molotov fully supported Stalin during the Great Purge. This was a time when many people were arrested and executed. In 1938 alone, 20 out of 28 government officials in Molotov's administration were executed. There is no record of Molotov trying to stop the purges or save anyone, unlike some other Soviet officials.

During the Great Purge, he approved 372 lists of people to be executed. This was more than any other Soviet official, including Stalin.

Later in his life, Molotov talked about his part in the purges of the 1930s. He said that even though there were mistakes and too many people were affected, the purges were needed. He believed they helped the Soviet Union avoid defeat in World War II. He said, "Socialism needs huge effort. And that includes sacrifices. Mistakes were made. But we could have lost more in the war if the leaders had hesitated and allowed disagreements." He added, "I am responsible for this policy of repression and think it was correct."

Minister of Foreign Affairs

In 1939, Adolf Hitler invaded the rest of Czechoslovakia. This broke the 1938 Munich Agreement. Stalin then believed that Britain and France, who had signed the agreement, would not be good allies against Germany. So, he decided to try to make peace with Nazi Germany. In May 1939, Maxim Litvinov, the Foreign Minister, was removed from his job. Molotov was appointed to take his place.

Molotov and Litvinov did not get along well. Litvinov thought Molotov was a small-minded schemer and involved in terrible acts.

Molotov was replaced as premier by Stalin.

At first, Hitler didn't want to make a treaty with the Soviets. But in August 1939, Hitler allowed his Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop to start serious talks. A trade agreement was made on August 18. On August 22, Ribbentrop flew to Moscow to sign a formal non-aggression treaty. This treaty is known as the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. However, it was Stalin and Hitler, not Molotov and Ribbentrop, who decided what would be in the treaty.

The most important part of the agreement was a secret plan. It divided Poland, Finland, and the Baltic States between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. It also allowed the Soviet Union to take Bessarabia (which is now Moldova). This secret plan gave Hitler permission to invade Poland, which he did on September 1.

The pact allowed Hitler to take two-thirds of Western Poland and all of Lithuania. Molotov was given freedom to act in Finland. In the Winter War, the Finns fought bravely, and the Soviets made mistakes. Finland lost a lot of land but kept its independence. The pact was later changed to give Lithuania to the Soviets. In return, Germany got a better border in Poland. These takeovers caused terrible suffering and many deaths in the countries involved. On March 5, 1940, Lavrentiy Beria gave Molotov, along with Anastas Mikoyan, Kliment Voroshilov, and Stalin, a note. It suggested executing 25,700 Polish officers. This event became known as the Katyn massacre.

In November 1940, Stalin sent Molotov to Berlin to meet Ribbentrop and Hitler. In January 1941, British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden visited Turkey. He tried to get Turkey to join the war on the Allies' side. Eden's visit was against Germany, not the Soviet Union. But Molotov thought otherwise. In talks with the Italian Ambassador, Molotov said the Soviets would soon face an invasion of the Crimea by Britain and Turkey. A British historian, D.C. Watt, said that based on Molotov's statements, it seemed that in early 1941, Stalin and Molotov saw Britain, not Germany, as the main threat.

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact guided Soviet–German relations until June 1941. That's when Hitler turned east and invaded the Soviet Union. Molotov was the one who told the Soviet people about the attack. He announced the war instead of Stalin. His speech, broadcast on radio on June 22, described the Soviet Union's role in a way similar to Winston Churchill's early wartime speeches. The State Defence Committee was formed soon after Molotov's speech. Stalin was chosen as chairman, and Molotov was chosen as deputy chairman.

After the German invasion, Molotov quickly negotiated with the British and then the Americans for wartime alliances. He took a secret flight to Scotland, where Anthony Eden met him. The dangerous flight in a high-altitude Tupolev TB-7 bomber went over German-occupied Denmark and the North Sea. From Scotland, he took a train to London to talk about opening a second front against Germany.

After signing the Anglo–Soviet Treaty of 1942 on May 26, Molotov went to Washington. Molotov met US President Franklin D. Roosevelt and agreed on a lend-lease plan. Both the British and the Americans only vaguely promised to open a second front against Germany. On his flight back to the Soviet Union, his plane was attacked by German fighters and later by Soviet fighters by mistake.

There is no proof that Molotov ever convinced Stalin to follow a different policy than what Stalin had already decided. One historian couldn't find any case where a top government official openly disagreed with Stalin.

There is some evidence that Stalin didn't like Molotov, even though he knew he needed him. Stalin's bodyguard once said, "More general dislike for this statesman robot and for his position in the Kremlin could scarcely be wished and it was apparent that Stalin himself joined in this feeling." At a party, Stalin's assistant whispered something to him. Stalin replied, "Does it have to be right away?" Everyone realized they were talking about Molotov. When Molotov arrived, his conversation with Stalin only lasted five minutes. But the fun of the party disappeared, and everyone spoke quietly. The bodyguard said, "Then the blanket left. Instantly the gaiety returned."

When Lavrenty Beria told Stalin about the Manhattan Project (the US atomic bomb project), Stalin chose Molotov to lead the Soviet atomic bomb project. However, the project developed very slowly under Molotov. So, Beria replaced him in 1944. When US President Harry S. Truman told Stalin that the Americans had created a powerful new bomb, Stalin told Molotov to speed up the Soviet project. Stalin ordered the Soviet government to invest much more money in it. Molotov also helped write the music and words for the 1944 version of the Soviet national anthem. He asked the writers to include lines about peace.

Molotov went with Stalin to the Tehran Conference in 1943, the Yalta Conference in 1945, and the Potsdam Conference after Germany was defeated. He represented the Soviet Union at the meeting in San Francisco that created the United Nations. In April 1945, Molotov talked with the new American President Harry S. Truman. These talks, though not hostile, were later seen as an early sign of the start of the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union. Even during the wartime alliance, Molotov was known as a tough negotiator. He strongly defended Soviet interests. Molotov lost his job as First Deputy Chairman on March 19, 1946.

From 1945 to 1947, Molotov attended all four conferences of foreign ministers from the winning countries of World War II. He was generally uncooperative with the Western powers. Molotov, following Soviet government orders, said the Marshall Plan was an attempt by powerful countries to control others. He claimed it was dividing Europe into two groups: capitalist and communist. In response, the Soviet Union and other Eastern European countries started the Molotov Plan. This plan created agreements between Eastern European states and the Soviet Union. It later became the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA).

After the war, Molotov's power started to decrease. A clear sign of his weakening position was that he couldn't stop his Jewish wife, Polina Zhemchuzhina, from being arrested for "treason" in December 1948. Stalin had not trusted her for a long time. Molotov first protested by not voting to condemn her. But he later changed his mind. He said, "I feel deep regret for not stopping Zhemchuzhina, a person very dear to me, from making her mistakes and from forming ties with anti-Soviet Jewish nationalists." He then divorced Zhemchuzhina.

Polina Zhemchuzhina became friends with Golda Meir, who came to Moscow in November 1948 as the first Israeli representative to the Soviet Union. There are claims that Zhemchuzhina, who spoke Yiddish, translated for a meeting between Meir and her husband, the Soviet foreign minister. However, Meir's own book My Life does not support this claim.

Zhemchuzhina was held in the Lubyanka prison for a year. Then she was sent away for three years to a distant Russian city. She was forced to do hard labor and spent five years exiled in Kazakhstan. Molotov had no contact with her except for small bits of news from Beria, whom he disliked. Zhemchuzhina was freed right after Stalin died.

In 1949, Andrey Vyshinsky replaced Molotov as Foreign Minister. But Molotov kept his job as First Deputy Premier and his membership in the Politburo. Molotov was first made Foreign Minister by Stalin to help with talks with Nazi Germany, replacing a Jewish predecessor. He was later removed from the same position partly because his wife was also of Jewish background.

Molotov never stopped loving his wife. It is said he told his maids to make dinner for two every evening. He said it was to remind him that "she suffered because of me." According to one source, Molotov said about her: "She's not only beautiful and intelligent, the only woman minister in the Soviet Union; she's also a real Bolshevik, a real Soviet person." Stalin's daughter said that Molotov became very obedient to his wife, just as he was to Stalin.

After the War: Later Career

At the 19th Party Congress in 1952, Molotov was chosen for the new group that replaced the Politburo, called the Presidium. But he was not listed among the members of a new secret group within the Presidium. This showed that Stalin no longer favored him. At the 19th Congress, Stalin said that Molotov and Mikoyan had been criticized by the Central Committee for mistakes. These mistakes included publishing a wartime speech by Winston Churchill that was positive about the Soviet Union's war efforts. Both Molotov and Mikoyan were quickly losing favor. Stalin told other leaders that he no longer wanted to see Molotov and Mikoyan around. At his 73rd birthday, Stalin treated both of them with disgust. In his speech at the 20th Party Congress in 1956, Khrushchev said that Stalin had plans to "finish off" Molotov and Mikoyan after the 19th Congress.

After Stalin's death, the leadership changed, and Molotov's position became stronger. Georgy Malenkov, who took over as General Secretary, made Molotov Minister of Foreign Affairs again on March 5, 1953. Right after Stalin died, many thought Molotov might become the new leader. However, he never tried to become the top leader of the Soviet Union. A group of three leaders was formed right after Stalin's death: Malenkov, Beria, and Molotov. This group ended when Malenkov and Molotov tricked Beria. Molotov supported the removal and later the execution of Beria, ordered by Khrushchev. The new Party Secretary, Khrushchev, soon became the new leader of the Soviet Union. He started to make the country more open and improve foreign relations. This included making peace with Josip Broz Tito's government in Yugoslavia, which Stalin had removed from the communist movement. Molotov, who was an old supporter of Stalin, seemed out of place in this new environment. But he still represented the Soviet Union at the Geneva Conference of 1955.

Molotov's position became weaker after February 1956. That's when Khrushchev unexpectedly criticized Stalin at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party. Khrushchev attacked Stalin for the purges of the 1930s and for the early defeats in World War II. He blamed these on Stalin trusting Hitler too much and on the purges of the Red Army's leaders. Molotov was the most senior of Stalin's helpers still in government. He had played a big part in the purges. So, it became clear that Khrushchev's look into the past would likely lead to Molotov losing power. Molotov became the leader of an older group that tried to remove Khrushchev.

In June 1956, Molotov was removed as Foreign Minister. On June 29, 1957, he was kicked out of the Presidium (Politburo). This happened after he tried and failed to remove Khrushchev as First Secretary. Molotov's group first won a vote in the Presidium 7–4 to remove Khrushchev. But Khrushchev refused to resign unless the Central Committee decided so. In the Central Committee meeting, Molotov and his group were defeated. He was then sent away to be ambassador to the Mongolian People's Republic. Molotov and his friends were called the "Anti-Party Group." But it's important to note that they didn't face the harsh punishments that were common for officials who fell out of favor during Stalin's time. In 1960, he was made the Soviet representative to the International Atomic Energy Agency. This was seen as a small step towards him being accepted back. However, after the 22nd Party Congress in 1961, Khrushchev continued his de-Stalinization campaign. This included moving Stalin's body from Lenin's Mausoleum. Molotov, along with Lazar Kaganovich, was removed from all positions and kicked out of the Communist Party. In 1962, all of Molotov's party documents were destroyed by the government.

In retirement, Molotov did not regret his actions under Stalin's rule. He had a heart attack in January 1962. After the Sino-Soviet split (a disagreement between China and the Soviet Union), it was reported that he agreed with Mao Zedong's criticisms of Khrushchev's policies.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1968, it was reported that Molotov had finished writing his memoirs, but they were not published then. The first signs that Molotov was being accepted back into public life appeared during Leonid Brezhnev's time as leader. Information about him was again allowed in Soviet encyclopedias. His connection to the Anti-Party Group was mentioned in encyclopedias published in 1973 and 1974. But this mention disappeared by the mid-to-late 1970s. Later, Soviet leader Konstantin Chernenko further helped Molotov's public image. In 1984, Molotov was even allowed to try to rejoin the Communist Party. A book of interviews with Molotov from 1969 to 1986 was published in 1993. It was called Molotov Remembers: Inside Kremlin Politics.

In June 1986, Molotov was taken to Kuntsevo Hospital in Moscow. He passed away there on November 8, 1986, during the time of Mikhail Gorbachev's rule. During his life, Molotov had seven heart attacks but lived to be 96 years old. When he died, he was the last major person still alive who had been part of the events of 1917. He was buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.

Molotov, like Stalin, was very suspicious of others. Because of this, much important information disappeared. Molotov once said, "One should listen to them, but it is necessary to check up on them. The intelligence officer can lead you to a very dangerous position.... There are many provocateurs here, there, and everywhere." Molotov continued to claim in published interviews that there was never a secret land deal between Stalin and Hitler during the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. Like Stalin, he never saw the Cold War as a global event. He saw it more as the usual conflict between communism and capitalism. He divided capitalist countries into two groups: the "smart and dangerous imperialists" and the "fools." Before he retired, Molotov suggested creating a socialist group with the People's Republic of China. Molotov believed that socialist states were part of a larger, united group. In retirement, Molotov criticized Nikita Khrushchev for being too moderate.

The Molotov cocktail is a name given by the Finns during the Winter War. It's a general name for different homemade fire weapons. During the Winter War, the Soviet air force used many firebombs and cluster bombs against Finnish civilians, soldiers, and defenses. When Molotov said on the radio that they were not bombing but delivering food to the hungry Finns, the Finns started calling the air bombs Molotov bread baskets. Soon, they fought back by attacking tanks with "Molotov cocktails," calling them "a drink to go with the food." According to one historian, the Molotov cocktail was a part of Molotov's public image that he probably didn't like.

Winston Churchill mentioned many meetings with Molotov in his wartime memories. He called Molotov "a man of outstanding ability and cold-blooded ruthlessness." Churchill concluded: "In the conduct of foreign affairs, Mazarin, Talleyrand, Metternich, would welcome him to their company, if there be another world to which Bolsheviks allow themselves to go." The former US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles said: "I have seen in action all the great international statesmen of this century. I have never seen such personal diplomatic skill at so high a degree of perfection as Molotov's."

Molotov was the only person known to have shaken hands with Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Adolf Hitler, Rudolf Hess, Hermann Göring, and Heinrich Himmler. At the end of 1989, the Soviet Union's government officially said that the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was wrong.

In January 2010, a Ukrainian court said that Molotov and other Soviet officials were responsible for causing a terrible famine in Ukraine in 1932–33. The court then stopped the legal process against them because the trial would have been after their deaths.

Molotov in Movies and Games

- Luther Adler played Molotov in the 1958 TV show Playhouse 90 episode The Plot to Kill Stalin.

- Clive Merrison played Molotov in the 1992 drama film Stalin.

- Michael Palin played Molotov in the 2017 comedy film The Death of Stalin.

- Russian actor Sergey Shanin played a character similar to Molotov in the 2023 video game Atomic Heart.

Awards and Honors

- Hero of Socialist Labour (1943)

- Four Orders of Lenin (1940, 1943, 1945, 1950)

- Order of the Badge of Honour

- Medal "For the Defence of Moscow" (1944)

- Medal "For the Victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (1945)

- Medal "For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (1945)

- Medal "In Commemoration of the 800th Anniversary of Moscow" (1947)

- Medal "Veteran of Labour" (1974)

- Jubilee Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin" (1969)

- Jubilee Medal "Forty Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (1985)

- Order of the Red Banner (Mongolia)

More to Explore

In Spanish: Viacheslav Mólotov para niños

In Spanish: Viacheslav Mólotov para niños

- Foreign relations of the Soviet Union

- Molotov Line

- Germany–Soviet Union relations, 1918–1941

- Molotov cocktail