Rudolf Hess facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Rudolf Hess

Reichsleiter

|

|

|---|---|

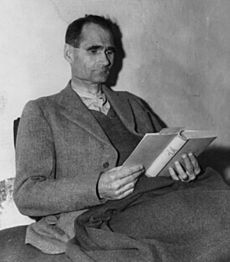

Hess in 1935

|

|

| Deputy Führer of the Nazi Party | |

| In office 21 April 1933 – 12 May 1941 |

|

| Führer | Adolf Hitler |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Martin Bormann (Chief of the Party Chancellery) |

| Reichsminister without portfolio | |

| In office 1 December 1933 – 12 May 1941 |

|

| Chancellor | Adolf Hitler |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess

26 April 1894 Alexandria, Khedivate of Egypt |

| Died | 17 August 1987 (aged 93) Spandau Prison, West Berlin, West Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Political party | Nazi Party (1920–1941) |

| Spouse |

Ilse Pröhl

(m. 1927) |

| Children | Wolf Rüdiger Hess |

| Alma mater | University of Munich |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | German Empire |

| Branch/service | Imperial German Army |

| Years of service | 1914–1918 |

| Rank | Leutnant der Reserve |

| Unit |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards | Iron Cross, 2nd Class |

| Criminal conviction | |

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Conviction(s) | Conspiracy to commit crimes against peace Crimes of aggression |

| Trial | Nuremberg trials |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment |

Rudolf Hess (born 26 April 1894 – died 17 August 1987) was a German politician. He was a very important member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. In 1933, he became the Deputy Führer (leader) to Adolf Hitler.

Hess held this position until 1941. That year, he flew alone to Scotland. He hoped to make a peace deal for the United Kingdom to leave World War II. Instead, he was captured. After the war, he was found guilty of planning aggressive wars. He spent the rest of his life in prison and died in 1987.

Hess joined the Imperial German Army when World War I started in 1914. He was hurt several times and received the Iron Cross. Before the war ended, he trained to be a pilot. He left the army in 1918. In 1919, Hess studied at the University of Munich. There, he learned about geopolitics from Karl Haushofer. Haushofer's ideas about "living space" (Lebensraum) became a key part of Nazi beliefs.

Hess joined the Nazi Party in 1920. He was with Hitler during the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923. This was a failed attempt by the Nazis to take over the government in Bavaria. While in prison for this, Hess helped Hitler write his book, Mein Kampf. This book became the main ideas for the Nazi Party.

After Hitler became Chancellor in 1933, Hess was made Deputy Führer. He was also elected to the German parliament (Reichstag). He became a minister in Hitler's government. Hitler said that Hermann Göring would be his successor, and Hess would be next in line. Hess often spoke for Hitler at events. He also signed many government laws. This included the Nuremberg Laws of 1935. These laws took away rights from Jewish people in Germany.

On 10 May 1941, Hess flew alone to Scotland. He hoped to talk with the Duke of Hamilton. Hess believed the Duke was against the British government's war plans. British authorities arrested Hess when he landed. He was held until the war ended. Then, he was sent back to Germany for the Nuremberg trials in 1946. During his trial, Hess pretended to have lost his memory. He later admitted it was a trick. He was found guilty of planning aggressive wars. He spent his life sentence in Spandau Prison. The Soviet Union stopped all efforts to release him early. He died in 1987 at age 93.

After his death, Spandau Prison was torn down. This was to stop it from becoming a place where neo-Nazis would gather. His grave also became a meeting place for neo-Nazis. In 2011, his family agreed to have his remains dug up and cremated. His ashes were scattered at sea.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Rudolf Hess was born on 26 April 1894. He was the oldest of three children. His family was wealthy and lived in Alexandria, Egypt. At that time, Egypt was under British control. His family was from Germany and owned an import business.

Hess's time in Egypt made him admire the British Empire. He believed that white people, especially from countries like Britain and Germany, should rule the world. He thought they should work together.

From 1900 to 1908, Hess went to a German school in Alexandria. Then, he was sent to a boarding school in Germany. He was good at science and math. But his father wanted him to join the family business. So, in 1911, he studied business in Switzerland. After a year, he started an apprenticeship at a trading company in Hamburg.

Service in World War I

Just weeks after World War I began, Hess joined the army. He fought against the British in France. He was at the First Battle of Ypres. In 1915, he received the Iron Cross. He was promoted several times.

Hess was wounded twice in 1917 while fighting in Romania. He recovered in hospitals in Hungary and Germany. In October, he was promoted to officer.

While still recovering, Hess asked to train as a pilot. He started flight training in March 1918. He finished advanced training in France in October. On 14 October, he joined a fighter squadron. But the war ended on 11 November 1918. So, he did not fight as a pilot.

Hess left the army in December 1918. His family's business in Egypt had been taken by the British. Hess joined the Thule Society, a right-wing group that was against Jewish people. He also joined the Freikorps, which were volunteer military groups.

In 1919, Hess studied history and economics at the University of Munich. His professor, Karl Haushofer, taught about "living space" (Lebensraum). This idea suggested Germany should take more land in Eastern Europe. Hess later shared this idea with Adolf Hitler. It became a main part of Nazi Party beliefs.

Hess met Ilse Pröhl at the university in 1920. They married in 1927. Their only child, Wolf Rüdiger Hess, was born in 1937. His name, Wolf, honored Hitler, who often used it as a code name.

Joining the Nazi Party

In 1920, Hess heard Hitler speak for the first time. He became very loyal to Hitler. They both believed that Germany lost World War I because of a plot by Jewish people and communists. Hess joined the Nazi Party on 1 July. He helped with fundraising and organizing. In 1921, he was hurt protecting Hitler at a party event. By 1922, Hess joined the Sturmabteilung (SA), which was the Nazi Party's private army. He helped organize and recruit its first members.

In 1923, Germany had many economic problems. Hitler decided to try to take over the government. This was called the Beer Hall Putsch. On 8 November 1923, Hess was with Hitler when they stormed a meeting in Munich. Hitler announced a new government. The next day, Hitler and his supporters marched to the Ministry of War. There was a fight with the police. Many people were killed. Hitler was arrested on 11 November.

Hess had taken some important people hostage. He later fled to Austria but was convinced to return. He was arrested and sentenced to 18 months in prison. Hitler was sentenced to five years. Both were held in Landsberg Prison. While there, Hess helped Hitler write his book, Mein Kampf. This book explained the Nazi Party's political ideas.

Hitler was released in December 1924, and Hess ten days later. The Nazi Party was allowed again in 1925. It grew quickly. In April 1925, Hitler made Hess his private secretary. Hess went with Hitler to speeches and became his close friend. Hess was one of the few people who could see Hitler without an appointment. His power in the Party grew. In 1932, Hess became head of the Party Liaison Staff.

Hess loved flying. He got his pilot's license in 1929. He owned several planes and spent many hours flying. When World War II started, Hess asked Hitler to let him join the air force. Hitler said no and told him to stop flying during the war.

Becoming Deputy Führer

On 30 January 1933, Hitler became the leader of Germany. On 21 April, Hess was named Deputy Führer of the Nazi Party. He became one of the 16 most important leaders in the Party. In December, he became a minister in Hitler's government. Hess had offices in Munich and Berlin. He was in charge of many departments, like foreign affairs and education. All new laws had to go through his office for approval. He also helped organize the yearly Nuremberg Rallies and often gave the opening speech.

Hess also spoke on the radio and at rallies across the country. His speeches were even collected into a book. Because Hess was born abroad, Hitler had him oversee Nazi Party groups in other countries. Hess was also allowed to review court decisions about people seen as enemies of the Party. He could increase sentences or even order people to concentration camps or to be killed.

In 1933, Hess started the Volksdeutscher Rat (Council of Ethnic Germans). This group handled the Nazi Party's relations with German people living in other countries. Hess's office also helped write Hitler's Nuremberg Laws of 1935. These laws banned marriage between non-Jewish and Jewish Germans. They also took away German citizenship from non-Aryan people. Hess's friend Karl Haushofer was married to a half-Jewish woman. So, Hess gave them special papers to be exempt from these laws.

Hess was very loyal to Hitler. He did not seek power or wealth for himself. He lived in a simple house. Hess strongly believed in the Nazi ideas. He thought there was a Jewish plot against Germany. In his speeches, he often blamed Jewish people for problems. For example, he blamed them for the Spanish Civil War.

On 30 August 1939, just before World War II started, Hitler made Hess part of his war cabinet. After the Invasion of Poland in September 1939, Hitler named Hess as second in line to succeed him, after Hermann Göring. Around this time, Hitler also made Martin Bormann his personal secretary. Bormann slowly took over many of Hess's duties.

Hess's hatred of Jewish people grew after the war began. He believed Jewish people caused the war. In a speech in 1940, Hess blamed "Jews and their friends" for Germany's surrender in 1918. He said that with Hitler in charge, the current war would not end the same way.

Hess was very concerned about his health. He was a vegetarian and did not smoke or drink. He loved music, reading, and hiking. He was also interested in astrology and fortune-telling.

Flight to Scotland

As the war continued, Hitler focused on military matters. Hess became less important. Martin Bormann had taken over many of his roles. Hess worried that Germany would have to fight a war on two fronts. This was because plans were being made to invade the Soviet Union in 1941. Hess decided to try and make peace with Britain himself. He planned to fly to Britain to talk to their government.

On 31 August 1940, Hess met with Karl Haushofer. Haushofer told Hess that he believed the British King wanted to remove Winston Churchill. Haushofer thought it was possible to contact the King through the Duke of Hamilton. Hess decided to contact the Duke of Hamilton. He mistakenly believed the Duke was against the war with Germany. Haushofer wrote to Hamilton, but the letter was stopped by British intelligence.

Hess decided to go ahead with his plan even without a reply. He started training to fly a Messerschmitt Bf 110, a two-engine aircraft. He practiced many cross-country flights. He had a special plane prepared with extra fuel tanks.

The Flight and Capture

On 10 May 1941, Hess took off from Augsburg, Germany, in his special plane. He had tried to leave before, but bad weather or mechanical problems stopped him. He wore a flying suit and carried money, maps, and medicines.

He flew across the North Sea. British radar detected his plane. Two Spitfire planes were sent to find him, but it was dark, and Hess was flying very low. He was almost out of fuel. He climbed to 6,000 feet and parachuted out of the plane. He hurt his foot when he landed. His plane crashed about 12 miles (19 km) from Dungavel House, the Duke of Hamilton's home. Hess was proud of this flight.

Before leaving Germany, Hess had given his assistant a letter for Hitler. It explained his plan to make peace with the UK. Hess hoped the Duke of Hamilton would help him negotiate peace. Hitler was very upset when he read the letter. He worried that his allies, Italy and Japan, would think he was secretly trying to make peace. Hitler told the German press to say that Hess was crazy and flew to Scotland on his own.

Hitler took away all of Hess's positions. He secretly ordered Hess to be shot if he ever returned to Germany. He gave Hess's old duties to Martin Bormann. Hitler also ordered the arrest of many astrologers and occultists. This was part of a plan to make Hess look bad.

Some people thought Hitler sent Hess to tell Churchill about the upcoming invasion of the Soviet Union. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin believed the British had planned Hess's flight. Churchill later said that Hess came on his own. He called Hess's plan "lunatic benevolence."

After the war, Hess told Albert Speer that his idea came from a dream. He believed supernatural forces told him to go. He thought Germany would guarantee Britain's empire if Britain gave Germany a free hand in Europe. Hess also told a journalist that Germany could not win a war on two fronts. He said he knew that fighting England was not the way.

Capture and Interrogation

Just before midnight on 10 May 1941, Hess landed near Glasgow, Scotland. A local farmer, David McLean, found him. Hess said his name was "Captain Alfred Horn" and that he had an important message for the Duke of Hamilton. McLean helped Hess to his cottage and called the local Home Guard. Hess was taken to the police station. He kept asking to meet the Duke of Hamilton.

The Duke of Hamilton arrived the next morning. Hess immediately told him his real identity. He explained why he flew to Scotland. Hamilton told Hess he hoped to continue the talk with an interpreter. Hess could speak English well, but had trouble understanding Hamilton. He said he was on a "mission of humanity" and that Hitler wanted to stop fighting with England.

After the meeting, Hamilton examined the plane crash site. He then met with Churchill. Churchill sent another expert, Ivone Kirkpatrick, to identify Hess. Hess, who had prepared many notes, spoke to them about Hitler's plans. He said Britain should let the Nazis control Europe. In return, Britain could keep its overseas lands. Hess later started to claim his medical treatment was bad. He also thought there was a plot to poison him.

News of Hess's flight was announced in Germany on 12 May. Hitler told Joachim von Ribbentrop to tell Mussolini the news. The British press was allowed to report the full story on 13 May. Hess's wife learned he was alive from German radio on 14 May.

Parts of Hess's plane were saved. One engine is at the RAF Museum. Another engine and part of the plane's body are at the Imperial War Museum.

Trial and Imprisonment

Hess was held in a fortified mansion in Surrey, England, for 13 months. Churchill ordered that Hess be treated well. But he could not read newspapers or listen to the radio. Hess was allowed to write to his family. He kept asking to meet the Duke of Hamilton, but his requests were denied. Psychiatrists who treated Hess said he was mentally unstable. He often complained of being poisoned and not being able to sleep.

While in Scotland, Hess claimed a "secret force" was controlling the minds of British leaders. He said this force made them hate Germany. He also claimed Jewish people had psychic powers. He thought they controlled the minds of others, including Heinrich Himmler.

In June 1942, Hess tried to escape by jumping over a staircase railing. He broke his leg. Around this time, he began to claim he had lost his memory. This might have been a trick. If he was declared mentally ill, he could be sent back to Germany.

Hess was moved to a hospital in Wales. He stayed there for three years. He was allowed walks and car trips. He could read and write letters. He became sad that Germany was losing the war. He stopped eating for a week until he was threatened with force-feeding.

Germany surrendered in May 1945. Hess was charged as a war criminal. He was sent to Nuremberg for trial in October 1945.

The Nuremberg Trials

The Allies held trials for major war criminals from November 1945 to October 1946. Hess was one of 23 defendants. They were charged with planning aggressive wars and other crimes.

When Hess arrived in Nuremberg, he was thin. He had a poor appetite. He was watched all the time. He was handcuffed to a guard outside his cell.

Soon after arriving, Hess started acting like he had lost his memory. The main psychiatrist thought he was partly faking it. Hess later admitted he faked memory loss to avoid a death sentence.

The prosecution argued that Hess knew about Hitler's plans for war. They said he signed important laws, like those about military service and the Nuremberg racial laws. They argued he was responsible for the regime's actions. They also said his flight to Scotland was an attempt to keep Britain out of the war.

Hess's lawyer argued that Hess was not responsible for events after he left Germany in May 1941. He also said Hitler alone made all the important decisions. Hess spoke to the court on 31 August 1946. He made a long statement.

The court decided on 30 September. Hess was found guilty of planning and preparing an aggressive war. He was also found guilty of conspiring with other German leaders to commit crimes. He was found not guilty of war crimes. He received a life sentence. He was one of seven Nazis to get prison sentences. They were sent to Spandau Prison in Berlin on 18 July 1947. The Soviet judge thought Hess should have received the death sentence.

Life in Spandau Prison

Spandau Prison was controlled by the UK, France, the United States, and the Soviet Union. Each country provided guards for a month. Hess was given the number 7. Prisoners were not allowed to talk to each other without permission. They had to help with cleaning and gardening. They could walk outside for an hour each day. Over time, some rules became less strict.

Visitors were allowed once a month. But Hess did not let his family visit until 1969. By then, his son was 32 and his wife was 69. They had not seen him since 1941. After this, he allowed regular visits. His daughter-in-law often brought photos of his grandchildren.

Hess continued to have health problems, both mental and physical. He often cried out at night, claiming stomach pains. He still suspected his food was poisoned. A psychiatrist in 1957 said he was not sick enough for a mental hospital.

Hess spent the rest of his life in Spandau Prison. Other inmates were released in the 1950s and 1960s due to health or after serving their time. From 1966 until Hess's death in 1987, he was the only prisoner. The prison cost a lot to maintain for just one person. In the 1980s, conditions improved. Hess could move more freely. He watched TV, read, and gardened.

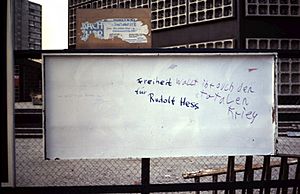

Hess's lawyer tried many times to get him released. But the Soviets always said no. Spandau was in West Berlin, which gave the Soviets a presence there. Also, Soviet officials believed Hess knew about the attack on their country in 1941. In 1967, Hess's son, Wolf Rüdiger Hess, started a campaign to free his father. Many politicians supported it, but it did not work. The Soviets said Hess had never shown any regret.

Hess remained a Nazi and anti-Semite. This was often ignored by those who wanted him released. They showed him as a harmless old man. Hess also made it harder to be released by writing statements he planned to make to the media. In 1986, a guard caught the prison chaplain trying to sneak out a statement by Hess. Hess had written this statement for his trial in 1946. In it, he claimed Germany attacked the Soviet Union first because the Soviets planned to attack Germany. He said his flight to Scotland was to warn the UK about the Soviet danger. He believed this warning would make the UK join Germany against the Soviet Union.

Death and Aftermath

Hess was found dead on 17 August 1987. He was 93 years old. He was in a small house in the prison garden used for reading. He was first buried in a secret place to avoid media attention. But his body was later re-buried in his family plot in Wunsiedel, Germany, in 1988. His wife was buried next to him in 1995.

Hess's grave in Wunsiedel became a place for neo-Nazis to visit and protest. To stop this, the local council decided not to renew the grave's lease in 2011. With his family's permission, Hess's grave was opened on 20 July 2011. His remains were cremated, and his ashes were scattered at sea. The gravestone, which said "I dared it," was destroyed. Spandau Prison was torn down in 1987 to prevent it from becoming a neo-Nazi shrine.

For a long time, some people believed the prisoner in Spandau was not the real Hess. But a study in 2019 used DNA testing. It showed a 99.99 percent match between the prisoner's DNA and a living male relative of Hess. This proved that the prisoner was indeed Rudolf Hess.

See also

In Spanish: Rudolf Hess para niños

In Spanish: Rudolf Hess para niños

- List of Nazi Party leaders and officials

- List SS-Obergruppenführer

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |