Theodore Hall facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Theodore Hall

|

|

|---|---|

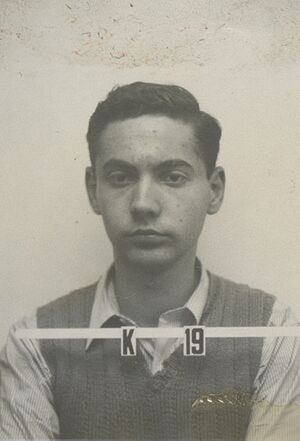

Hall's ID badge photo from Los Alamos

|

|

| Born |

Theodore Alvin Holtzberg

October 20, 1925 New York City, New York, U.S.

|

| Died | November 1, 1999 (aged 74) |

| Education | Queens College Harvard University (BS) University of Chicago (MS) |

| Occupation | Physicist |

| Employer | Manhattan Project |

| Known for | Atomic espionage |

| Relatives | Edward N. Hall (brother) |

Theodore Alvin Hall (born October 20, 1925 – died November 1, 1999) was an American physicist. He became known as an atomic spy for the Soviet Union. During World War II, he worked on the Manhattan Project. This was a secret U.S. effort to build the first atomic bombs. Hall shared details about the "Fat Man" plutonium bomb and how to make plutonium pure with Soviet intelligence.

His older brother, Edward N. Hall, was also a scientist. Edward was a rocket scientist who helped create the U.S. Air Force's intercontinental ballistic missile program. He designed the Minuteman missile.

Contents

Growing Up and Education

Theodore Alvin Holtzberg was born in Far Rockaway, New York City. His parents were Jewish immigrants. His father was a furrier who came to America to escape violence against Jewish people in the Russian Empire. Theodore's mother died when he was a teenager. The Great Depression made it hard for his father's business. So, the family moved to Washington Heights.

Even when he was young, Theodore was very good at math and science. His older brother Edward, who was 11 years older, often taught him. Theodore skipped three grades in elementary school. In 1937, he started at Townsend Harris High School for gifted boys. He visited the 1939 New York World's Fair and was very impressed by the Soviet display.

In 1940, at age 14, he was accepted into Queens College. In 1942, he moved to Harvard University to study physics. He graduated from Harvard at 18 in 1944.

In 1936, his brother Edward legally changed both their last names to Hall. This was to avoid problems getting jobs because of their Jewish background.

Working on the Manhattan Project

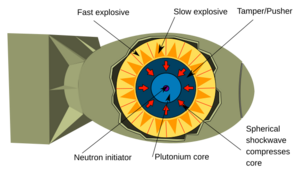

At 18, Theodore Hall became the youngest physicist to work on the Manhattan Project. This secret project was at Los Alamos. First, he helped figure out the amount of uranium needed for the "Little Boy" bomb. Then, he worked on tests for the "Fat Man" bomb's implosion system. Even as a teenager, he led a team working on this difficult task.

Hall later said he became worried in 1944. Germany was losing the war and would not build an atomic bomb. He feared what would happen if the U.S. was the only country with atomic weapons. He was especially concerned about a possible harsh government in the U.S. if it had such a powerful weapon. Other scientists shared these worries. They knew that General Leslie Groves, who led the Manhattan Project, had said the real target for the U.S. bomb was the Soviet Union. This led some scientists, like Josef Rotblat, to quit the project. Others, like Niels Bohr and Leo Szilard, tried to stop the bomb's use or tell the Soviets about it.

In October 1944, Hall went to New York City for his 19th birthday. He visited Amtorg, a Soviet trading company. There, he got the name of Sergey Nikolaevich Kurnakov, a writer. Hall gave Kurnakov a report about the scientists at Los Alamos, the conditions there, and the basic science of the bomb. Hall's friend and roommate, Saville Sax, also delivered the same report to the Soviet Consulate.

Hall and Sax later met with Anatoli Yatskov, a Soviet agent. Yatskov sent their information to Moscow. Hall was given the code-name MLAD, meaning "young." Sax was given the code-name STAR, meaning "old."

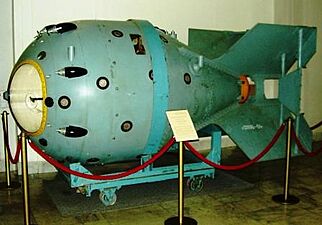

Information from Hall, Klaus Fuchs, and David Greenglass helped the Soviets build their first atomic device, "RDS-1". It looked very much like the "Fat Man" bomb. Hall was the only known scientist to give details on the atomic bomb's design for a long time.

Life After Los Alamos

In June 1946, the U.S. Army removed Hall's security clearance. This was not because they suspected him of spying. It was because of a joking letter from his sister-in-law and some left-wing magazines he received. Hall was honorably discharged from the military.

That fall, he went to the University of Chicago. He earned his master's and doctoral degrees in physics. He also met his wife and started a family. After graduating, he became a biophysicist.

In Chicago, he helped create new ways to analyze materials using X-rays. In 1952, he moved to Memorial Sloan-Kettering in New York City. He worked there as a biophysicist. In 1962, he moved to Cambridge University in England. There, he developed the Hall Method. This method helped analyze thin biological tissues. He worked at Cambridge until he retired in 1984 at age 59.

Hall also worked to get signatures for the Stockholm Peace Pledge.

Later Years and Death

Theodore Hall died on November 1, 1999, in Cambridge, England. He was 74. He had Parkinson's disease. But he died from renal cancer, which is kidney cancer. This cancer was likely caused by his work with plutonium during the Trinity test.

FBI Investigation and Confessions

The U.S. Army's Signal Intelligence Service had a secret project called Venona project. They decoded some Soviet messages. In January 1950, they found a message naming Hall and Sax as Soviet spies. But this document was not made public until July 1995. Before then, most spying on the Los Alamos project was blamed on Klaus Fuchs.

The FBI questioned Hall in March 1951. But he was not charged with a crime. The FBI said they couldn't use the Venona document in court. They didn't want the Soviets to know their secret code was broken.

However, journalist Dave Lindorff found Hall's FBI file in 2021. This file showed that J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI Director, wanted to pursue Hall. But Gen. Joseph F. Carroll of the Air Force stopped him. Carroll feared that arresting Hall would cause the Air Force to lose Edward Hall, their top missile expert, during a time of strong anti-communist feelings. Edward Hall was later promoted and finished the Minuteman missile program.

Lindorff helped make a 2022 movie called A Compassionate Spy about Hall's life. In 2023, Lindorff wrote a book, Spy for No Country: The Story of Ted Hall, the Teenage Atomic Spy Who May Have Saved the World.

Hall's Statements in the 1990s

The Venona project became public in July 1995.

In 1997, Hall wrote a statement. He almost admitted that the Soviet spy message about him was true. He said that after the war, he felt that "an American monopoly" on nuclear weapons "was dangerous." He believed it "should be avoided."

He said:

To help prevent that monopoly I thought about meeting a Soviet agent. I just wanted to tell them about the A-bomb project. I expected a very short meeting. With some luck, it might have been that way, but it wasn't.

A year before he died, in 1998, he gave a clearer confession in a TV interview. He said:

I decided to give atomic secrets to the Russians because it seemed important that no one country should have all the power. A monopoly could make one nation a danger to the world, like ... Nazi Germany became. There seemed to be only one answer to what I should do. The right thing was to act to break the American monopoly.

See also

- Klaus Fuchs

- Oscar Seborer

- Saville Sax

- Lona Cohen

- Morris Cohen (spy)

- Manhattan Project

- Los Alamos

- J. Robert Oppenheimer

- Oppenheimer security hearing

- Atomic spies

- Soviet espionage in the United States

- Nuclear espionage

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |