Kola Peninsula facts for kids

Kola Peninsula as a part of Murmansk Oblast

|

|

Location of Murmansk Oblast within Russia

|

|

| Geography | |

| Location | Northwest Russia |

| Coordinates | 67°41′18″N 35°56′38″E / 67.68833°N 35.94389°E |

| Adjacent bodies of water | |

| Area | 100,000 km2 (39,000 sq mi) |

| Length | 370 km (230 mi) |

| Width | 244 km (151.6 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,201 m (3,940 ft) |

| Highest point | Yudychvumchorr |

| Administration | |

|

Russia

|

|

| Oblast | Murmansk Oblast |

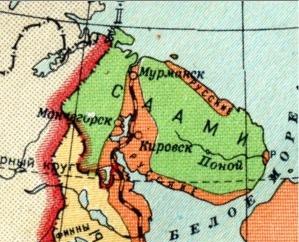

The Kola Peninsula (Russian: Кольский полуостров, romanized: Kolsky poluostrov) is a large piece of land surrounded by water on most sides. It is located in the far northwest of Russia and is one of the biggest peninsulas in Europe. Most of the Kola Peninsula is inside the Arctic Circle, a special area around the North Pole. The Barents Sea borders it to the north, and the White Sea is to its east and southeast.

The city of Murmansk is the biggest city on the peninsula. About 270,000 people live there. People first settled in the northern part of the peninsula a very long time ago, around 7,000 to 5,000 BCE. Later, other groups arrived from the south. By the year 1000 CE, only the Sami people lived there.

Things changed in the 12th century when Russian Pomors discovered the peninsula's rich hunting and fishing areas. Soon, people from the Novgorod Republic came to collect taxes. The peninsula slowly became part of Novgorod's lands. However, Novgorodians did not build permanent towns until the 15th century.

During the Soviet era (1917–1991), many more people moved to the Kola Peninsula. Most new residents lived in cities along the coast and near railroads. The Sami people were forced to join collective farms and move to central villages like Lovozero. The peninsula became very industrial and important for the military. This was because of its location and the discovery of huge apatite mineral deposits in the 1920s. Sadly, this led to a lot of environmental damage.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the economy struggled. The population dropped from 1,150,000 in 1989 to 795,000 in 2010. However, the peninsula has improved in the 21st century. Today, it is the most developed and urbanized area in northern Russia.

Even though it is far north, the Kola Peninsula has warmer winters than expected. This is because of the North Atlantic Current, which is part of the Gulf Stream. But this also causes strong winds. Summers are cool, with an average July temperature of only 11°C (52°F). The southern part of the peninsula has taiga forests, while the north has tundra. In the tundra, permafrost (ground that is always frozen) stops trees from growing tall. Instead, you see shrubs and grasses. The peninsula is home to different mammals, and its rivers are important for Atlantic salmon. The Kandalaksha Nature Reserve protects birds like the common eider.

The Kola Peninsula is also famous for the Kola Superdeep Borehole. This is the deepest hole ever drilled into the Earth.

Contents

Geography of the Kola Peninsula

Where is the Kola Peninsula?

The Kola Peninsula is in the far northwest of Russia. It is almost entirely located inside the Arctic Circle. The Barents Sea is to its north, and the White Sea is to its east and southeast. Geologically, it sits on the northeastern edge of the Baltic Shield, a very old and stable part of the Earth's crust.

The western border of the peninsula runs from the Kola Bay along the Kola River valley, through Lake Imandra, and down the Niva River to the Kandalaksha Gulf. Some maps show the border extending further west to Russia's border with Finland.

The peninsula covers an area of about 100,000 square kilometers (38,600 sq mi). The northern coast is steep and high, while the southern coast is flat. In the western part, you can find two mountain ranges: the Khibiny Mountains and the Lovozero Massif. The highest point on the peninsula, Yudychvumchorr, is in the Khibiny Mountains. Its height is 1,201 meters (3,940 ft).

Administratively, the peninsula includes several districts and parts of territories controlled by cities like Murmansk, Kirovsk, and Apatity.

Natural Resources of the Kola Peninsula

The Kola Peninsula is very rich in different ores and minerals. This is because the last ice age removed the top layer of soil. You can find apatite and nepheline here, which are used to make fertilizers. There are also deposits of copper, nickel, and iron ore. Other minerals include mica, kyanite, and materials for ceramics. Even rare-earth elements and non-ferrous ores are present.

Building materials like granite, quartzite, and limestone are also common. Near lakes, there are deposits of diatomaceous earth, which is used for insulation.

Climate of the Kola Peninsula

The peninsula's closeness to the Gulf Stream means winters are unusually warm for such a northern place. This causes big temperature differences between the land and the Barents Sea, leading to strong winds. Cyclones are common in cold seasons, while anticyclones happen in warm seasons. Monsoon winds are typical in most areas. Strong storm winds blow for 80–120 days each year. The waters along the Murman Coast stay warm enough to not freeze, even in winter.

The Kola Peninsula gets a lot of precipitation (rain and snow). Mountains get about 1,000 mm (39 in) per year. The Murman Coast gets 600–700 mm (24–28 in), and other areas get 500–600 mm (20–24 in). The wettest months are August to October, while March and April are the driest.

The average temperature in January is about -10°C (14°F). Central parts of the peninsula can be even colder. In July, the average temperature is about +11°C (52°F). Record low temperatures can reach -50°C (-58°F) in central areas. Record highs can go above +30°C (86°F) almost everywhere on the peninsula. The first frosts can happen as early as August and last until May or even June.

Most of the Kola Peninsula has a subarctic climate. Nearby islands usually have a tundra climate.

| Climate data for Murmansk (Climate ID:22113) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

29.4 (84.9) |

30.8 (87.4) |

32.9 (91.2) |

30.2 (86.4) |

24.2 (75.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

9.6 (49.3) |

7.2 (45.0) |

32.9 (91.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −7 (19) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

2.6 (36.7) |

7.6 (45.7) |

13.6 (56.5) |

17.3 (63.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

3.8 (38.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −10.1 (13.8) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.8 (55.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

0.6 (33.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −13.2 (8.2) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.7 (42.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

8.0 (46.4) |

4.5 (40.1) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −39.4 (−38.9) |

−38.6 (−37.5) |

−32.6 (−26.7) |

−21.7 (−7.1) |

−10.4 (13.3) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−2 (28) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−21.2 (−6.2) |

−30.5 (−22.9) |

−35 (−31) |

−39.4 (−38.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 30 (1.2) |

22 (0.9) |

23 (0.9) |

24 (0.9) |

36 (1.4) |

53 (2.1) |

70 (2.8) |

61 (2.4) |

52 (2.0) |

51 (2.0) |

38 (1.5) |

34 (1.3) |

494 (19.4) |

| Source: Roshydromet | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Sosnovets Island (Climate ID:22355) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

4.4 (39.9) |

5.1 (41.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.7 (80.1) |

17.8 (64.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

9.1 (48.4) |

7.4 (45.3) |

26.7 (80.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −9.0 (15.8) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

9.1 (48.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

2.7 (36.9) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−0.2 (31.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −33.1 (−27.6) |

−33.2 (−27.8) |

−35.3 (−31.5) |

−24.1 (−11.4) |

−14.9 (5.2) |

−6 (21) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−6 (21) |

−13.7 (7.3) |

−22.5 (−8.5) |

−31.1 (−24.0) |

−35.3 (−31.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 19 (0.7) |

16 (0.6) |

20 (0.8) |

19 (0.7) |

33 (1.3) |

43 (1.7) |

45 (1.8) |

49 (1.9) |

42 (1.7) |

45 (1.8) |

27 (1.1) |

25 (1.0) |

383 (15.1) |

Plants and Animals of the Kola Peninsula

The southern part of the peninsula is covered by taiga forests, while the north has tundra. In the tundra, it's cold and windy, and the ground is always frozen (permafrost). This means trees can't grow tall. Instead, you'll see grasses, wildflowers, and shrubs like dwarf birch and cloudberry. Along the northern coast, stony and shrub lichens are common. The taiga forests in the south are mostly made up of pine trees and spruces.

Reindeer herds visit the grasslands in summer. Other animals living here include red and Arctic foxes, wolverines, moose, otters, and lynx in the southern areas. American minks were brought here in the 1930s and are now common. Beavers, which almost disappeared by 1880, were brought back in the mid-1900s. In total, thirty-two types of mammals and up to two hundred bird species live on the peninsula.

Beluga whales are the only cetacean (a type of marine mammal) commonly found around the peninsula. Other dolphins, like Atlantic white-sided dolphins and white-beaked dolphins, also visit. Large whales, such as bowhead, humpback, blue, and finback whales, are seen here too.

The coasts of the Kandalaksha Gulf and the Barents Sea are important places for bearded seals and ringed seals to have their babies. The Barents Sea is one of the few places where rare Gray seals can be found. Harp seals also appear sometimes.

There are twenty-nine types of freshwater fish in the peninsula's rivers and lakes. These include trout, stickleback, northern pike, and European perch. The rivers are very important for Atlantic salmon, which return from Greenland and the Faroe Islands to lay their eggs in fresh water. Because of this, fishing for fun has become popular, with special lodges for sport-fishermen. The Kandalaksha Nature Reserve was set up in 1932 to protect common eider birds. It has thirteen parts located in the Kandalaksha Gulf and along the Barents Sea coasts.

Rivers and Lakes of the Kola Peninsula

The Kola Peninsula has many rivers. They are usually small but flow very fast with rapids. Some of the most important rivers are the Ponoy, the Varzuga, the Umba, the Teriberka, the Voronya, and the Yokanga. Most rivers start from lakes and swamps and get their water from melting snow. The rivers freeze over in winter, but areas with strong rapids might freeze later or not at all.

The major lakes include Imandra, Umbozero, and Lovozero. There are no lakes smaller than 0.01 square kilometers (0.004 sq mi). Fishing for fun is a popular activity in the region's lakes.

Environmental Concerns on the Kola Peninsula

The Kola Peninsula has faced significant environmental damage. This is mainly due to pollution from military activities, industrial mining of apatite, and military nuclear waste. For example, about 137 active and 140 unused or shut down naval nuclear reactors from the Soviet military are still on the peninsula. For thirty years, nuclear waste was dumped into the sea by the Northern Fleet and a shipping company. There is also evidence of pollution from the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, with harmful substances found in reindeer meat.

The main source of industrial pollution comes from Norilsk Nickel in Monchegorsk. Their large smelters are responsible for most of the sulfur dioxide emissions and nearly all nickel and copper emissions. Since 1998, sulfur dioxide emissions have dropped by almost 60%. Norilsk Nickel plans to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions by 95% by 2030. Other polluters include power stations in Apatity and Murmansk.

History of the Kola Peninsula

Early Settlements and People

The Rybachy Peninsula in the north of Kola was settled as early as 7,000 to 5,000 BCE. Later, around 3,000 to 2,000 BCE, people from the south (modern Karelia) moved to the peninsula. An important Bronze Age site, where ancient DNA has been found, is on Bolshoy Oleny Island in the Kola Bay.

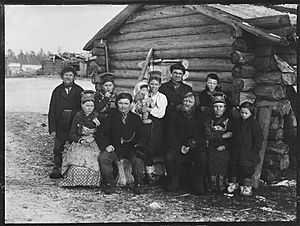

By the end of the 1st millennium CE, only the Sami people lived on the peninsula. They did not have their own state but lived in clans led by elders. They mostly herded reindeer and fished. In the 12th century, Russian Pomors from the White Sea coast discovered the peninsula's rich hunting and fishing grounds. The Pomors regularly visited to hunt and fish, and they traded with the Sami. They called the White Sea coast of the peninsula the Tersky Coast.

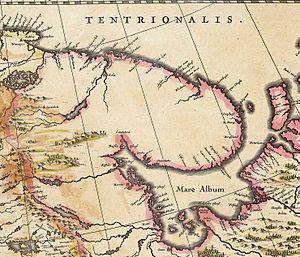

By the late 12th century, the Pomors had explored the entire northern coast and reached Finnmark in Norway. The Pomors called the northern coast Murman, which was a changed form of Norman, meaning "Norwegian."

Novgorod and Russian Control

Soon after the Pomors, tax collectors from the Novgorod Republic arrived. The Kola Peninsula slowly became part of Novgorod's lands. Treaties in the 13th and 14th centuries helped define the borders between Novgorod and Scandinavian countries. The Treaty of Novgorod in 1326 ended conflicts with Norway. This treaty meant Norway gave up its claims to the Kola Peninsula. However, the Sami people continued to pay taxes to both Norway and Novgorod until 1602.

In the 15th century, Novgorodians started building permanent settlements. Umba and Varzuga were among the first, dating back to 1466. Eventually, most coastal areas in the west were settled by Novgorodians. The Novgorod Republic lost control of these lands to the Grand Duchy of Moscow after a battle in 1471. In 1478, Novgorod itself became part of Moscow. All its territories, including those on the Kola Peninsula, joined the Grand Duchy of Moscow.

Russian migration to the peninsula continued in the 16th century. New settlements like Kandalaksha were founded. The Sami and Pomor people were forced into serfdom, a system where they were tied to the land. In the late 16th century, the peninsula became a point of disagreement between Russia and Denmark–Norway. Russia strengthened its position by appointing a voyevoda (a military governor) in Kola, which became the region's main administrative center.

Permanent settlement on the peninsula did not really pick up until the 1860s. Even then, it was slow until 1917. In 1887, many Izhma Komi and Nenets people moved to the peninsula with their large reindeer herds. They were escaping a reindeer disease epidemic in their homelands. This led to competition for grazing lands and conflicts between the Komi and the Sami. By the end of the 19th century, most Sami people were forced to move north, and ethnic Russians settled in the south.

In 1894, the Russian Minister of Finance visited and saw the region's economic potential. A telephone and telegraph line were extended to Kola in 1896. Also in 1896, Alexandrovsk (now Polyarny) was founded and grew quickly.

During World War I, the Kola Peninsula became very important. Communication between Russia and its allies was cut, and the ice-free harbors on the Murman Coast were the only way to send war supplies. In 1915, a railroad was quickly built and opened in 1916. In 1916, Romanov-na-Murmane (now Murmansk) was founded as the end point of the new railroad. It quickly became the largest city on the peninsula.

The Soviet and Modern Eras

Soviet power began on the peninsula in November 1917. However, forces from Russia's allies occupied the area from March 1918 to March 1920. In June 1921, the Soviet government created Murmansk Governorate. Later, in 1927, it became Murmansk Okrug and part of Leningrad Oblast. This changed again in 1938, when it became the modern Murmansk Oblast.

During the Soviet period, the population grew a lot, from 15,000 in 1913 to 799,000 in 1970. Most people lived in cities along the railroads and coast. The less populated areas were used for reindeer herding. New towns and work settlements were built in the 1920s–1940s.

The Sami people faced forced collectivization in the 1920s–1930s. More than half of their reindeer herds were taken by the state. Traditional Sami herding methods were replaced by new ones that focused on permanent settlements. This caused the Sami people to lose some of their language and traditional knowledge. Many Sami were forced to live in Lovozero, which became their cultural center in Russia. Repression against the Sami continued until Stalin's death in 1953.

Thousands of people were sent to Kola in the 1930s–1950s, often as forced labor. Many were peasants from southern Russia. Prisoner labor was used to build new factories and work in them.

During the Cold War, the peninsula was a very important naval base for the Soviet Union. It protected against and posed a threat to northern Norway.

Population of the Kola Peninsula

Before the 1800s, the Kola Peninsula had very few people, only about 5,200 in 1858. In 1868, the Russian government offered reasons for people to move there. Not only Russians but also Finns, Norwegians, and Karelians came to the peninsula. By the 1897 census, 9,291 people lived in the Kola area. Most were Russian (63%), followed by Sami (19%), Finnish (11%), and Karelian (3%).

By 1913, about 13,000–15,000 people lived on the peninsula, mostly along the coasts. But when huge natural resources were found and industries grew during Soviet times, the population exploded. By 1970, the population was around 799,000. This trend changed in the 1990s after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The population of the entire Murmansk Oblast fell from 1,150,000 in 1989 to 795,000 in 2010.

According to the 2010 Census, most of the population is Russians (89.0%). Other groups include Ukrainians (4.8%) and Belarusians (1.7%). Smaller groups are Komi (about 1,600 people), Sami (about 1,600), and Karelians (about 1,400). The native Sami people mostly live in Lovozersky District.

Economy of the Kola Peninsula

How the Economy Developed

In the 15th–16th centuries, people on the Tersky Coast mainly fished for Atlantic salmon, hunted seals, and made salt from seawater. Monasteries mostly ran the salt production. For a long time, this was the only "industry" on the peninsula.

By the mid-16th century, Atlantic cod fishing grew on the Murman Coast. International trade also increased, with Russian merchants trading with Western European merchants.

During the 17th century, salt production slowly declined because local salt was more expensive than salt from other regions. Too much hunting also reduced the number of pearls found. Commercial deer herding became more popular, but it was not a big part of the economy until the 19th century. By the late 17th century, it was common for people to set up temporary fishing and hunting camps in the north.

Peter the Great saw the importance of the peninsula and encouraged its industries and trade. But the region was less important after St. Petersburg was founded in 1703, as most shipping moved there. In 1732, large amounts of silver were found on Medvezhy Island. Copper, silver, and gold were also found near the Ponoy River. Despite efforts for two centuries, these discoveries did not lead to big commercial success. In the late 18th century, local people learned to produce peat for heating from the Norwegians. The timber cutting industry grew in the late 19th century.

The Soviet era brought huge industrial growth and military development to the peninsula. In 1925–1926, large deposits of apatite were found in the Khibiny Mountains. The first apatite was shipped just a few years later, in 1929. Other mineral deposits, like sulfide, iron ore, and titanium ores, were found in the 1930s.

Fishing was always important. In the 1920s–1930s, the Murmansk Trawl Fleet was created, and fishing facilities grew. By 1940, fishing made up 40% of the region's economy and 80% of Murmansk's economy.

During the Cold War, the peninsula was a key naval base for the Soviet Union's navy and air forces. It was important for defense and posed a threat to northern Norway.

Current Economy

After a tough economic period in the 1990s, the region's economy started to improve in the 2000s. Today, the Kola Peninsula is the most industrial and urbanized area in northern Russia. The main port is Murmansk, which is the administrative center of Murmansk Oblast. This port does not freeze in winter. Even though the peninsula is less important for the military now, it still has the highest number of nuclear weapons, reactors, and facilities in Russia.

Mining is the most important part of the region's economy. Mining companies are the main employers in towns like Apatity, Kirovsk, and Monchegorsk. The Kola Mining and Metallurgical Company mines nickel, copper, and platinum-group-metals. Other big mining companies produce phosphates and iron ore.

The fishing industry is still profitable, even though it produces less than it did in Soviet times. In 2006, it supplied 20% of Russia's fish, and this amount has been growing. Murmansk is a key base for three fishing fleets, including Russia's largest. Fish farming, especially of salmon and trout, is also growing.

The energy sector includes the Kola Nuclear Power Plant near Polyarnye Zori, which produces about half of all energy. The other half comes from seventeen hydroelectric plants and two thermal power stations. The peninsula produces more energy than it needs, sending about 20% to Russia's main energy system and exporting some to Norway and Finland.

Transportation is very important for the economy, making up 11% of the region's total economic output. The Kola Peninsula has ship transport, air transport, road transport, and electric public transport. It also has access to railways. The city of Murmansk is an important port on the Northern Sea Route. The largest airports are Murmansk Airport and Kirovsk-Apatity Airport.

See also

In Spanish: Península de Kola para niños

In Spanish: Península de Kola para niños

- Kola Superdeep Borehole

- Lake Kildinskoye

- Lake Semyonovskoye

- Sápmi

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |