Fin whale facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Fin whale |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| A fin whale surfacing in Greenland | |

|

|

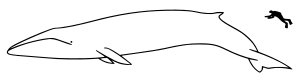

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Balaenopteridae |

| Genus: | Balaenoptera |

| Species: |

B. physalus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Balaenoptera physalus (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

|

| Subspecies | |

|

|

|

|

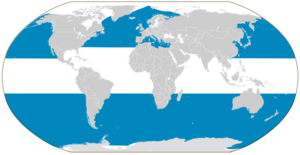

| Fin whale range | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

Balaena physalus Linnaeus, 1758 Balaena boops Linnaeus, 1758 Balaena antiquorum Fischer, 1829 Balaena quoyi Fischer, 1829 Balaena musculus Companyo, 1830 Balaenoptera rorqual Lacépède, 1804 Balaenoptera gibbar Lacépède, 1804 Balaenoptera mediterraneensis Lesson, 1828 Balaenoptera jubartes Dewhurst, 1834 Balaenoptera australis Gray, 1846 Balaenoptera patachonicus Burmeister, 1865 Balaenoptera velifera Cope, 1869 Physalis vulgaris Fleming, 1828 Rorqualus musculus F. Cuvier, 1836 Pterobalaena communis Van Beneden, 1857 |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) is also known as the finback whale or common rorqual. It is a type of baleen whale and the second-longest cetacean (a group that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises) after the blue whale. The largest fin whales can grow up to 27 m (89 ft) long and weigh as much as 80 tonnes (88 short tons; 79 long tons).

Fin whales have long, thin, brownish-gray bodies. Their underside is paler, which helps them blend in with the bright surface when seen from below. This is called countershading. They live in all major oceans, from cold polar waters to warm tropical areas. However, they avoid waters very close to the ice at the poles and small areas away from the open ocean. They are most common in temperate and cool waters.

Fin whales mostly eat small schooling fish, tiny squid, and small crustaceans like copepods and krill. They usually mate in warmer, low-latitude seas during the winter. These whales often travel in groups of 6 to 10 animals. They communicate using low-frequency sounds, from 16 to 40 hertz.

Like other large whales, fin whales were heavily hunted in the past. This happened especially from the 1840s into the 20th century. Over 725,000 fin whales were caught in the Southern Hemisphere between 1905 and 1976. Because of this, their numbers dropped a lot. Even by 2100, the southern fin whale population is expected to be less than half of what it was before whaling. This is due to the long-term effects of whaling and how slowly they recover. As of 2018, the IUCN lists the fin whale as a vulnerable species.

Contents

Understanding Fin Whales

What is a Fin Whale?

Fin whales belong to a group called rorquals. This family, Balaenopteridae, also includes the humpback whale, blue whale, Bryde's whale, sei whale, and minke whale. These whales are all baleen whales, meaning they have special plates in their mouths instead of teeth to filter food from the water.

Scientists first described the fin whale in the 1600s and 1700s. Carl Linnaeus officially named the species Balaena physalus in 1758. The word physalus comes from a Greek word meaning "blows," which refers to the fin whale's strong blow (the spray of water from its blowhole).

Fin Whale Family Tree

Fin whales are part of a large family of whales. Scientists use DNA to understand how different whale species are related. {{cladogram |align=right |caption=A phylogenetic tree of six baleen whale species |clades=

| Balaenopteridae |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This diagram shows how fin whales are related to other baleen whales. It suggests that fin whales might be more closely related to humpback whales and even gray whales than to some whales in their own genus, like minke whales.

Fin Whale Subspecies

As of 2023, there are four recognized subspecies of fin whales. Each subspecies has slightly different physical traits and sounds.

- The northern fin whale (B. p. physalus) lives in the North Atlantic Ocean.

- The southern fin whale (B. p. quoyi) lives in the Southern Hemisphere.

- Fin whales in the North Pacific are considered a third subspecies, possibly named B. p. velifera.

These different groups usually do not mix with each other.

Whale Hybrids

Sometimes, a fin whale and a blue whale can have a baby together. This baby is called a hybrid. Hybrids have features from both parents. Even though blue whales and fin whales are different species, these hybrids happen fairly often in the North Atlantic and North Pacific.

For example, in 2018, a whale caught off Iceland was found to be a hybrid. Its mother was a blue whale and its father was a fin whale. Scientists have also found that about 3.5% of the genes in North Atlantic blue whales come from fin whales. This shows that fin whale males can successfully mate with blue whale females.

Fin Whale Body and Features

Fin whales have a thin body with a slender snout. They have a large, hook-like dorsal fin located towards the back of their body. Along their back, they have a long ridge. Inside their mouths, they have about 350 to 400 baleen plates. Like all rorquals, fin whales have special grooves that run from their lower jaw to their belly button. These grooves help them expand their mouths when feeding.

Only the blue whale is larger than the fin whale. Adult fin whales usually weigh between 40 and 50 tonnes. Females are generally longer and heavier than males. Males average 21 m (69 ft) in length, while females average 22 m (72 ft). The largest fin whales can reach over 27 m (89 ft) long and weigh up to 80 tonnes (88 short tons). Some estimates suggest they could weigh up to 120 tonnes (130 short tons).

Fin whales are brownish to dark or light gray on their backs and white on their bellies. A unique feature is their head color: the left side is dark gray, but the right side has a complex pattern of light and dark markings. The right lower jaw is white or light gray, and this color sometimes extends to the upper jaw. They also have dark, oval-shaped areas of color called "flipper shadows" below their pectoral fins.

The fin whale's mouth has a very stretchy nerve system. This helps them open their mouths wide to scoop up large amounts of food.

Fin Whale Life Cycle and Reproduction

Fin whales mate during the winter months in warmer, low-latitude waters. The gestation period (how long the mother carries the baby) lasts about 11 to 12 months. Usually, only one baby is born at a time, though sometimes more have been reported.

A newborn calf is about 11 to 12 m (36 to 39 ft) long. It weans (stops drinking milk from its mother) at 6 or 7 months old. The calf then travels with its mother to the summer feeding areas. Females typically reproduce every two to three years. In the Northern Hemisphere, females become sexually mature between 6 and 12 years old, when they are about 19 m (62 ft) long. In the Southern Hemisphere, they mature around 20 m (66 ft). Calves stay with their mothers for about a year.

Fin whales reach their full physical maturity between 25 and 30 years of age. They can live for at least 94 years, and some have been estimated to live up to 135–140 years. Fin whales are among the fastest cetaceans. They can swim steadily at speeds between 37 km/h (23 mph) and 41 km/h (25 mph). They can even burst to speeds up to 46 km/h (29 mph), which is why they are sometimes called "the greyhound of the sea."

Fin whales are more social than some other rorquals. They often live in groups of 6 to 10 whales. However, when they are feeding, groups can grow much larger, sometimes up to 100 animals.

Whale Vocalizations

| Multimedia relating to the fin whale

The whale calls have been sped up 10x from their original speed.

|

Male fin whales make long, loud, low-frequency sounds. The sounds made by blue and fin whales are the lowest-frequency sounds of any animal. Most of their sounds are frequency-modulated (FM) pulses that sweep downwards. These sounds are in the infrasonic range, from 16 to 40 hertz. (Most humans can hear sounds between 20 hertz and 20 kilohertz).

Each sound lasts one to two seconds. These sounds combine into patterns that last 7 to 15 minutes. The whale then repeats these patterns for many days. These loud sounds can be heard hundreds of miles away.

When US biologists first recorded fin whale sounds, they didn't know what they were. They thought the sounds might be from broken equipment, natural earth movements, or even a secret Soviet Union plan to find submarines! Eventually, scientists figured out that these sounds were made by fin whales.

These vocalizations are linked to the mating season, and only males make them. This suggests the sounds might be a way for males to attract females. Over the last 100 years, increased ocean noise from ships and naval activities might have made it harder for fin whales to recover. This noise can make it difficult for males and females to communicate. Fin whale songs can even travel deep into the seafloor, which seismologists use to help with underwater surveys.

How Fin Whales Breathe

When fin whales are feeding, they blow (exhale) five to seven times quickly. When they are traveling or resting, they blow once every minute or two. Before their last dive, they arch their back high out of the water. However, they rarely lift their flukes (tail fins) out of the water. They can dive up to 470 m (1,540 ft) deep when feeding. When traveling or resting, they usually dive for only a few minutes at a time.

Fin Whale Habitat and Behavior

Where Fin Whales Live

Fin whales are found all over the world, in all major oceans. They live in waters from the cold polar areas to the warm tropical zones. They are not found in waters very close to the ice at the poles or in small areas away from the large oceans, like the Red Sea. However, they can enter places like the Baltic Sea. They are most common in temperate and cool waters and less common near the equator.

In the North Atlantic, fin whales live from the Gulf of Mexico and Mediterranean Sea all the way north to Baffin Bay. In the North Pacific, they are found from central Baja California to Japan and as far north as the Chukchi Sea near the Arctic Ocean. They are very common in the northern Gulf of Alaska and southeastern Bering Sea from May to October.

Fin whales do migrate, moving seasonally between feeding areas in high latitudes. However, their exact migration patterns are not fully understood. Sounds recorded from underwater listening devices suggest that North Atlantic fin whales migrate south in the autumn from the Labrador-Newfoundland region, past Bermuda, and into the West Indies. Some fin whales might stay in high latitudes all year, moving offshore but not south in late autumn. Studies show that young fin whales often learn migration routes from their mothers and return to the same feeding areas in later years.

In the Pacific, migration patterns are not well known. While some fin whales seem to stay in the Gulf of California all year, their numbers increase significantly in winter and spring. Southern fin whales migrate from their feeding grounds in the Antarctic during summer to warmer breeding and calving areas in winter. The exact locations of these winter breeding areas are still a mystery because these whales tend to migrate in the open ocean.

Scientists have found that fin whale populations in the Mediterranean Sea often feed in areas that also have high levels of plastic pollution and microplastic debris. This is likely because both microplastics and the whales' food sources are found in areas where deep, nutrient-rich water rises to the surface.

Before whaling began, the total fin whale population in the North Pacific was estimated to be between 42,000 and 45,000. About 25,000 to 27,000 of these lived in the eastern North Pacific. Recent surveys show much smaller numbers, for example, between 1,600 and 3,200 off California.

Who Hunts Fin Whales?

The only known predator of the fin whale is the killer whale. There are at least 20 reports of killer whales attacking or bothering fin whales. Fin whales usually try to escape and don't fight back much. Only a few confirmed deaths have been recorded. For example, in October 2005, 16 killer whales attacked and killed a fin whale in the Canal de Ballenas, Gulf of California. They chased it for about an hour before killing it.

What Fin Whales Eat

Fin whales are filter-feeders. This means they eat small schooling fish, squid, and crustaceans like copepods and krill. In the North Pacific, they mostly eat krill and small fish like anchovies and capelin. In the North Atlantic, they also eat krill and small fish like herring and sand eels. In the Southern Hemisphere, they almost only eat euphausiids, especially Antarctic krill.

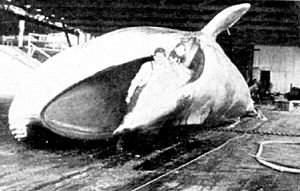

To eat, a fin whale opens its jaws wide while swimming at about 11 km/h (6.8 mph). This allows it to scoop up a huge amount of water, up to 70 m3 (18,000 US gal; 15,000 imp gal) in one gulp. Then, it closes its jaws and pushes the water out through its baleen plates. The baleen acts like a sieve, trapping the tiny prey inside while the water flows out. An adult fin whale has between 262 and 473 baleen plates on each side of its mouth. These plates are made of keratin (the same material as your fingernails) and have fine hairs on the ends. Each plate can be up to 76 cm (30 in) long.

Fin whales often dive more than 200 m (660 ft) deep to find krill. They perform an average of four "lunges" (big gulps) during a dive. Each gulp can give the whale about 10 kg (22 lb) of food. A single whale can eat up to 1,800 kg (4,000 lb) of food per day! Scientists believe fin whales spend about three hours a day feeding to get enough energy, which is similar to how much time humans spend eating. If food is not dense enough or is too deep, the whale has to spend more time searching. One hunting trick they use is to swim in circles around schools of fish very fast. This scares the fish into a tight ball, making it easier for the whale to turn on its side and swallow the whole group.

Whale Health and Parasites

Fin whales can get sick from various conditions. They can have parasites like the copepod Pennella balaenopterae, which burrows into their blubber to feed on blood. Barnacles like Xenobalanus globicipitis and Coronula reginae can attach to their fins or baleen. Other tiny creatures can also live on their baleen or skin.

A large nematode worm called Crassicauda boopis can infect fin whales. This worm can cause serious inflammation in the kidney arteries and potentially lead to kidney failure. Studies have shown that this parasite is very common and dangerous for fin whales, sometimes even causing death. The worms are likely spread through contaminated water.

In 1997, a sick fin whale found off the Belgian coast had a virus called Morbillivirus. In 2011, another sick fin whale found in Italy also had Morbillivirus and another parasite called Toxoplasma gondii. This whale also had high levels of pollutants in its body.

Fin Whales and Humans

History of Whaling

In the 1800s, fin whales were not often hunted by whalers in small boats. They were too fast and often sank after being killed, making them hard to catch. However, with the invention of steam-powered boats and harpoons that exploded, it became possible to hunt them on a large scale. As other whale species became rare, whalers started targeting the still-plentiful fin whale. They were hunted for their blubber, oil, and baleen. About 704,000 fin whales were caught in the Antarctic alone between 1904 and 1975.

The use of factory ships in 1925 greatly increased the number of whales caught each year. By the 1960s, fin whales became scarce, and whalers started hunting sei whales more. From the late 1800s to the 1960s, fin whales were a main target for whaling in the Sea of Japan.

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) banned fin whale hunting in the Southern Hemisphere in 1976. The Soviet Union illegally hunted protected whale species, often reporting them as fin whales to hide their actions. The IWC gave fin whales full protection from commercial whaling in the North Pacific in 1976 and in the North Atlantic in 1987. There are small exceptions for aboriginal hunts and for research. All fin whale populations worldwide are listed as endangered by the US National Marine Fisheries Service and the IUCN Red List.

The IWC allows Greenland to catch 19 fin whales per year. The meat from these hunts is sold in Greenland, but exporting it is illegal. Iceland and Norway do not follow the IWC's ban on commercial whaling because they disagreed with it.

In the Southern Hemisphere, Japan allowed itself to catch 10 fin whales per year for "research" between 2005 and 2007. From 2007 onwards, they planned to take 50 per year. In 2019, Japan left the IWC and started commercial whaling again. Japan reported catching 212 whales in both 2020 and 2021, but no fin whales have been reported in those catches yet.

Ship Collisions

Collisions with ships are a major cause of death for fin whales. In some areas, many large whale strandings (when whales get stuck on shore) are caused by ship strikes. Most serious injuries happen from large, fast-moving ships over or near continental shelves.

For example, a 60-foot fin whale was found stuck on the front of a container ship in New York harbor in 2014. In 2021, two dead fin whales were found stuck to the Australian destroyer HMAS Sydney when it arrived in Naval Base San Diego.

Ship collisions happen often in Tsushima Strait. To help prevent this, the Japan Coast Guard has started a program to watch for large whales in the strait and warn ships in the area.

Whale Watching

Fin whales are often seen during whale-watching tours around the world. In Monterey Bay and the Southern California Bight, fin whales can be seen all year. The best time to see them there is between November and March. You can even see them from land in some places, like Point Vicente, California, where they feed close to shore. They are also regularly seen in the summer and fall in places like the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the Gulf of Maine, the Bay of Fundy, and the Strait of Gibraltar. In southern Ireland, they are seen near the coast from June to February.

Protecting Fin Whales

As of 2018, there are an estimated 100,000 adult fin whales worldwide. About 70,000 are in the North Atlantic, 50,000 in the North Pacific, and 25,000 in the Southern Hemisphere.

The fin whale is listed as a vulnerable species on the IUCN Red List. They are also protected under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 in the US. The fin whale is listed on Appendix I and II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). Commercial whaling of fin whales was officially banned in 1976 in both the North Pacific and Southern Hemisphere. Since the ban, their populations have slowly increased. However, fin whales are still hunted off West Greenland and by Japanese researchers in the Antarctic Ocean.

Fin whales can also sometimes get caught in fishing gear. Military sonar (sound waves used by ships) might affect how fin whales behave, which could harm their populations. Also, whale watching activities might cause fin whales to change their behavior and feeding habits.

The fin whale is also protected by agreements like the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area (ACCOBAMS) and the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (Pacific Cetaceans MOU).

Interesting facts about fin whales

- It is the second largest animal on Earth after the blue whale.

- This whale is sometimes called the "greyhound of the sea" because of its fast swimming speed; it can swim up to 23 mph (37 km/hr) in short bursts.

- A newborn fin whale measures about 6.0–6.5 m (19.7–21.3 ft) in length and weighs about 1,800 kilograms (4,000 lb).

- The vocalizations of blue and fin whales are the lowest-frequency sounds made by any animal.

- Fin whale songs can penetrate over 2,500 m (8,200 ft) below the sea floor and seismologists can use those song waves to assist in underwater surveys.

- The only known predator of the fin whale is the killer whale.

- They often swim in groups of 6 to 10 animals, which is more social than some other large whales.

- One whale can consume up to 1,800 kg (4,000 lb) of food a day, leading scientists to conclude that the whale spends about three hours a day feeding to meet its energy requirements, roughly the same as humans.

- They can dive very deep to find food, sometimes over 400 meters (about 1,300 feet).

- In the 20th century, the fin whale was primarily hunted for its blubber, oil, and baleen. Around 704,000 fin whales were caught in Antarctic whaling operations alone between 1904 and 1975.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Rorcual común para niños

In Spanish: Rorcual común para niños

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |