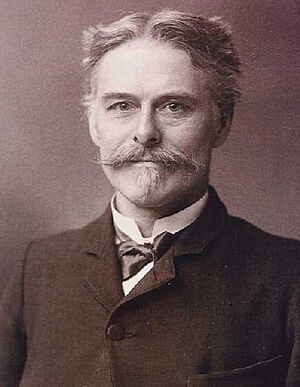

Edward Drinker Cope facts for kids

Edward Drinker Cope (born July 28, 1840 – died April 12, 1897) was an American biologist. He was famous for studying fossil animals from North America. Cope was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Cope was a paleontologist, which means he studied ancient life. He was also a comparative anatomist, a herpetologist (studying reptiles and amphibians), and an ichthyologist (studying fish). He wrote many scientific papers. His family were wealthy Quakers.

His father wanted him to be a farmer, but Edward chose to become a scientist. He married his cousin, Annie Pim. Later, they owned a museum in Philadelphia.

Cope mostly taught himself science by reading books. He did not work as a teacher for long. He loved doing field work, which meant going out to find fossils. In the 1870s and 1880s, he traveled to the Western United States. He helped the government map the land. He was often part of a team from the United States Geological Survey.

For a time, Cope had a big competition with another scientist named Othniel Charles Marsh. They both wanted to find the most dinosaurs. This rivalry was called the Bone Wars. Being a scientist sometimes cost Cope a lot of money. In the 1880s, he lost so much money from his silver mines that he had to sell many of his fossils in 1886. By the 1890s, he was no longer poor. However, he died when he was only 57 years old.

Cope published about 1,400 articles in science journals. He discovered over 1,000 species of extinct animals. He wrote about hundreds of types of ancient fish. He also found dozens of dinosaurs. He studied how mammalian molar teeth changed over time. He also wrote two large books about the amphibians and reptiles of North America.

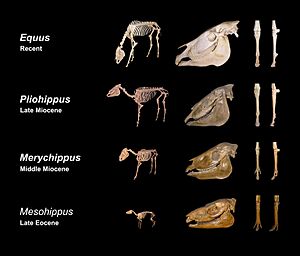

Cope showed that horses became larger as they moved from woodlands to grasslands. The idea that mammals tend to get bigger over time, as seen in fossils, is now called Cope's rule.

Contents

Cope's Early Life and Education

Edward Drinker Cope was the first son of Alfred and Hanna Cope. His father was a serious Quaker. He ran a shipping business that his own father had started. Edward's parents took him to gardens, museums, and zoos. They taught him to read, write, and draw.

Edward started school at age nine. When he was 12, his parents sent him to a Quaker boarding school. At 15, he began studying biology, also known as natural history. He often visited the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. This academy had a Natural history museum.

Cope's letters home showed he did not like farm work. His father made him work on a farm during summers when he was 14 and 15. When Edward was 16, his father stopped sending him to boarding school. He wanted Edward to become a farmer. His father even bought him a farm for more exercise. However, Cope rented the land to other farmers and only worked on farms part-time.

At 18, Cope started working part-time at the Academy of Natural Sciences. He also took classes there, paid for by his father. Still, his father insisted he should farm. Until he was 23, Cope kept writing to his father. He always said he wanted to be a scientist, not a farmer.

He worked at the Academy of Natural Sciences for two years. He then became a member. He sometimes visited the Smithsonian Institution. There, he met Spencer Baird, an expert on fish and birds. Cope also joined the American Philosophical Society. Both the Academy and the Society published scientific journals. They accepted his articles for publication.

In 1861, at age 21, Cope wrote about how to classify salamanders. A salamander is an amphibian. He then took a comparative anatomy class at the University of Pennsylvania. Cope asked his father if he could learn German and French. He wanted to read science books and novels in those languages.

Travels in Europe

When the American Civil War began, Cope tried to get a job helping in a field hospital. Then, at 22, he wanted to help freed slaves. In 1863, he and his fiancée broke up, which made him sad. He decided to travel to Ireland, England, and other parts of Europe. During his trip, he met many famous scientists.

While in Germany, he first met his future rival, Othniel Charles Marsh. On February 11, 1864, Cope wrote to his father. He said, "I shall get home in time to . . . be caught by the new draft." He added that he would not be sorry, as some people might think he went to Europe to avoid the war.

Cope's Early Career and Discoveries

Cope returned home to Philadelphia before the Civil War ended. He married Annie Pim, a Quaker girl he knew. She lived on a farm, and their wedding was held at her house.

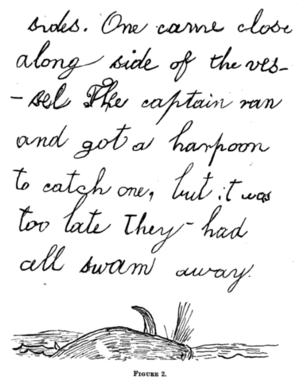

Cope wrote papers about fish, whales, and a fossil frog with a tail. Cope’s father gave money to Haverford College, a small Quaker school. The college gave Cope an honorary master's degree. They also hired him to teach Zoology.

Cope went on scientific trips to the American West. He wrote letters to his parents, wife, and daughter during these trips. He told his father that teaching took too much time. He felt it stopped him from making scientific discoveries. So, he quit his job at the college. He, his wife, and daughter then moved to Haddonfield, New Jersey. This was to be closer to the fossil beds in western New Jersey.

In Haddonfield, New Jersey, there were marlpits. These were places where a dinosaur skeleton was found in 1858. Dr. Leidy named it Hadrosaurus foulkii. Cope found more fossils in these marlpits. For example, he described Elasmosaurus platyurus and Laelaps in 1868. Edward Cope also explored caves. The last cave he visited was the Wyandotte Caves in Indiana in 1871.

In his 30s, Cope published many scientific papers. Charles Hazelius Sternberg, a fossil collector, said that Cope sometimes had bad dreams in the fossil fields of Kansas. He said every animal they found that day would appear in his dreams.

Cope also searched for fossils in the western United States. In 1872, he explored rocks from the Eocene period. These rocks were 55 to 38 million years old. That year, he worked too much and became very tired. In 1873, he studied the Titanothere beds in northeastern Colorado. Titanothere was a large, extinct plant-eating animal.

The Wheeler Survey

In 1874, Cope volunteered for the Wheeler Survey. These were geological mapping trips. They were led by George Montague Wheeler. The survey mapped parts of the United States west of the 100th meridian. This meridian is the line that separates the dry West from the rainy East of the United States.

In 1874, Cope discovered the Puerco formation in New Mexico during the Wheeler Survey. The Puerco formation was a layer of soft rock, 500 feet thick. It was along the upper Puerco River near Cuba, New Mexico. It contained green and black marl, which had chemicals used in fertilizer. Other scientists later found fossils in a similar rock layer nearby. Cope said these fossils came from his Puerco formation. This rock formation was new to the scientists he knew. As a volunteer for the Wheeler Survey, he paid his own way. He was able to get his findings included in the survey's reports. He even brought his wife and daughter on one trip, renting a house for them.

Working Independently

When Cope was 35, his father died. He left Cope a large sum of money, about a quarter of a million dollars. The next year, 1876, Cope moved his family back to Philadelphia. They moved into a row house in the city. He bought two houses next to each other. He used one as a lab for his fossil collection. He stopped doing field work to focus on writing. He hired teams to find fossils for him. He also helped set up fossil displays for the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition. In 1877, he was able to buy half of the American Naturalist journal.

He published papers so quickly that his rival, Professor Marsh, doubted when Cope's fossils were found. In August 1878, at age 38, Cope sailed to the British Isles. He attended a science convention in Dublin, Ireland. Then he sailed to France for another convention. At one of these meetings, he decided to buy some boxes of fossils from Argentina. These might have been for the museum in Philadelphia.

When Cope returned, two years' worth of fossils collected by his team were waiting for him. This included a Camarasaurus, which is a type of sauropod.

The Bone Wars: A Scientific Rivalry

Cope introduced his friend Marsh to Albert Vorhees, the owner of a marl pit. Later, Cope found out that Marsh had secretly made a deal with Vorhees. Any fossils found by Vorhees's workers would be sent to Marsh in New Haven.

In 1868, Professor Marsh pointed out a big mistake Cope had made. Cope had put the skull of a dinosaur at the tail end of its skeleton. This dinosaur was Elasmosaurus, a long-necked plesiosaur. Marsh was right, and Cope felt very embarrassed.

This mistake started a long and bitter rivalry between Cope and Marsh. It lasted for the rest of Cope’s life. Both scientists spent a lot of money trying to stop the other from digging for fossils. They often criticized each other's work in the New York Herald newspaper. Marsh even tried to stop Cope from publishing his articles and books. In response, Cope hired two fossil-finders who used to work for Marsh.

In 1889, the U.S. Geological Survey stopped giving money to Cope for his research. Marsh convinced John Wesley Powell, who led the Survey, to ask Cope to give back the fossils Cope found in 1874. Cope did not want to give them away. He had been a volunteer and paid his own way to find them. So, he spoke to the New York Herald.

The first article about their feud appeared on January 12, 1890. Cope claimed Marsh underpaid his workers. He also said some of Marsh's writings were actually done by others. Cope also accused Powell of misusing tax money and making mistakes in classifying fossils. Later, another article presented Marsh's side of the story. As a result of these articles, the Survey lost its funding for fossil-finding. Marsh was fired from the Survey. Cope almost lost his job at the University of Pennsylvania. Cope wondered if people thought he was "a liar . . . driven by jealousy." He seemed to regret that Marsh was fired. He wrote to paleontologist Henry Osborn, "I think Marsh is stuck on the horns of Monoclonius sphenocerus."

Cope's Later Years and Legacy

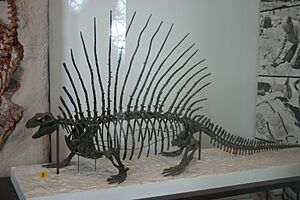

In 1882, Cope wrote a paper about a fossil pelycosaur called Edaphosaurus. It looked like a lizard with a huge fin on its back. In 1886, Professor Cope fired his fossil diggers. He started selling some of his large fossil collection to museums. That year, he also wrote forty more scientific reports about their findings.

In 1889, he reported on Coelophysis, a slender dinosaur from the Upper Triassic period. This small meat-eating dinosaur is one of the earliest dinosaurs ever found. The same year, Cope took over from Joseph Leidy as a professor of zoology at the University of Pennsylvania. Leidy had died the year before.

In 1892, Cope, then 52, received money for field work from the Texas Geological Survey. With his finances better, he published a huge book called Batrachians of North America. This was the most detailed work on the continent's frogs and amphibians ever done. He also published the 1,115-page book The Crocodilians, Lizards and Snakes of North America.

In the 1890s, he published even more, averaging 43 articles a year. His last trip to the West was in 1894. He searched for dinosaurs in South Dakota and visited sites in Texas and Oklahoma.

In 1895, Cope hired Sternberg again to look for fossils for him. Sternberg was the one who knew about Cope's dinosaur nightmares.

Cope sold many fossils to museums. For example, in 1895, the American Museum of Natural History in New York City bought his collection of about 10,000 fossil mammals.

Cope sold three other collections for $29,000. Although his collection still had over 13,000 specimens, it was much smaller than Marsh's collection, which was worth over a million dollars.

Cope's Death

In 1896, Cope became sick. He died on April 12, 1897. His friends shared their memories of him. Then, his will was read. The American Journal of Science published an obituary about Cope. The Naturalist had a longer one. Years later, the National Academy of Sciences' journal also published an obituary.

Cope's Ideas on Evolution

Edward D. Cope was a Quaker. His biographer, Henry Osborn, wrote that Cope may have had doubts about the Bible. However, he did not share them in letters to his family.

Cope's ideas about evolution changed over his lifetime. In his paper On the Origin of Genera (1868), he first thought that Charles Darwin's natural selection could explain small changes in organisms. But he believed it could not explain how new groups of animals (genera) formed.

Later, Cope's beliefs focused more on continuous evolution. He thought that a Creator was less involved. He became one of the founders of the Neo-Lamarckism idea. This idea suggests that animals can pass on traits they gain during their lifetime to their children. Even though this idea has been proven wrong, it was common among paleontologists in Cope's time. In 1887, Cope published his own book, Origin of the Fittest: essays in evolution. In it, he explained his views. He strongly believed in the "law of use and disuse." This meant that if an animal used a body part a lot, it would become stronger and larger over generations. This theory is not correct because using a body part does not change the genetic code that is passed down. This became clear in the years after his death.

Images for kids

-

Illustration plate from Cope's The Vertebrata of the Tertiary Formations of the Far West, showing skulls of Canidae (dog-like animals) from Oregon.

See also

In Spanish: Edward Drinker Cope para niños

In Spanish: Edward Drinker Cope para niños