Othniel Charles Marsh facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

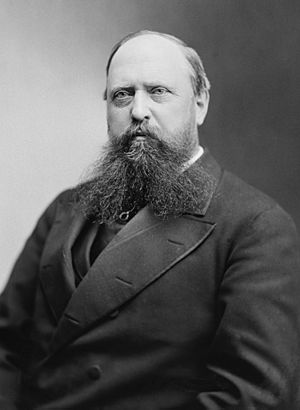

Othniel Charles Marsh

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | October 29, 1831 Lockport, New York, United States

|

| Died | March 18, 1899 (aged 67) |

| Citizenship | American |

| Alma mater | Yale College (BA, MA) University of Berlin |

| Awards | Bigsby Medal (1877) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Paleontology |

| Institutions | Yale University |

| Influences | James Dwight Dana |

| Influenced | John Bell Hatcher |

| Signature | |

Othniel Charles Marsh (born October 29, 1831 – died March 18, 1899) was an American professor who studied paleontology at Yale University. He was also the president of the National Academy of Sciences. Marsh was one of the most important scientists in the field of paleontology. He discovered or described many new species and developed theories about how birds came to be.

Marsh came from a family that didn't have much money. But he was able to go to college because his rich uncle, George Peabody, helped him. After finishing Yale College in 1860, he traveled the world. He studied anatomy, mineralogy, and geology. When he came back, he got a teaching job at Yale. From the 1870s to the 1890s, he had a big competition with another paleontologist named Edward Drinker Cope. This time was known as the Bone Wars, where they both rushed to find fossils in Western America.

Marsh's biggest achievement was collecting many fossils. These included reptiles from the Mesozoic Era, birds from the Cretaceous Period, and mammals from the Mesozoic and Tertiary periods. These collections are now a very important part of the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale and the Smithsonian Institution. People have called Marsh "a great paleontologist and the biggest supporter of Darwin's ideas in America during the 1800s."

Contents

About Othniel Charles Marsh

His Early Life and Education

Othniel Charles Marsh was born on October 29, 1831, in Lockport, New York, United States. His family was not wealthy; his father, Caleb Marsh, was a farmer. Marsh's mother, Mary Gaines Peabody, was the younger sister of a rich banker named George Peabody. Sadly, she died when Marsh was less than three years old.

Because his uncle, George Peabody, helped him financially, Marsh was able to get a good education. He graduated from Phillips Academy in 1856. Then, he earned his bachelor's degree with honors from Yale College in 1860.

Marsh received a special scholarship from Yale. He used it to study geology, mineralogy, and chemistry at Yale's Sheffield Scientific School from 1860 to 1862. He earned his master's degree in 1863. After that, he studied paleontology and anatomy in Europe, in cities like Berlin and Heidelberg, from 1862 to 1865. When he returned to the United States in 1866, he became a professor at Yale University. This made him the very first professor of paleontology in the United States.

In the same year, the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale was started. This happened because George Peabody donated $150,000, which Marsh had suggested. Marsh helped manage the Peabody Museum and was one of its first three curators.

Marsh's Discoveries and Career

Marsh received a large inheritance of $100,000 from his uncle, George Peabody. This money allowed Marsh and his many fossil hunters to find about 500 new kinds of fossil animals. Marsh himself later named all of these new species. He published almost 400 scientific articles during his career.

In May 1871, Marsh found the first pterosaur fossils ever discovered in America. He also described early horses and flying reptiles. He found and described many Cretaceous and Jurassic dinosaurs. These included famous ones like Triceratops, Stegosaurus, Brontosaurus, Apatosaurus, and Allosaurus. Marsh also described ancient birds with teeth, such as Ichthyornis and Hesperornis, which lived during the Cretaceous period.

Marsh's discoveries of horse fossils showed how horses had changed over time. This was very important because it helped prove Charles Darwin's theory of evolution using real fossils. Marsh, more than anyone else, provided the physical evidence to support Darwin's ideas. In 1876, a famous English biologist named Thomas Henry Huxley visited Marsh. Huxley's ideas about evolution were different from Marsh's at first. However, Marsh showed him his fossil collection and explained his findings. Huxley then changed his mind to agree with Marsh. He even used Marsh's discoveries as the main part of his famous lecture about the horse in New York.

In 1868, Marsh became a member of the American Philosophical Society.

In November 1874, Marsh went on a fossil-collecting trip to the White River Badlands. While there, he collected two tons of fossils. He also found out that the Red Cloud Agency, which was supposed to help Native Americans, was still being managed badly and had a lot of fraud. Marsh promised to tell officials in Washington about Red Cloud's complaints. Another group investigated and confirmed Marsh's claims. This led to several government officials losing their jobs. George Armstrong Custer praised Marsh for "exposing the well known frauds." Red Cloud himself said Marsh, "...told the Great Father everything just as he promised he would, and I think he is the best white man I ever saw."

Marsh started finding many Jurassic fossils in 1877. These were found in the Morrison Formation near Morrison, Colorado, in an area now called Dinosaur Ridge. Later that year, he learned about fossils at Como Bluff, Wyoming. His workers there found even more amazing fossils until 1889. Marsh's teams also dug near Canon City, Colorado, and in the Denver Beds. The workers from Morrison sent 230 large boxes of bones to Marsh at Yale. His Canon City workers sent 270 boxes, and 480 boxes came from Como Bluff. One of Marsh's biographers called this "truly the richest harvest of dinosaurs ever gathered by a single paleontologist."

Marsh's work on early mammals was also very important. In early 1878, Marsh was thrilled when one of his men at Como Bluff found a mammal fossil from the Jurassic period. This led to many more discoveries that greatly increased what we knew about Jurassic mammals. Marsh was able to describe new groups and species in every main mammal family.

In 1880, Marsh got the attention of scientists worldwide. He published a book called Odontornithes: a Monograph on Extinct Birds of North America. This book included his discoveries of ancient birds that had teeth. These bird skeletons helped connect dinosaurs to birds. They also gave very strong support for Darwin's theory of evolution. Darwin himself wrote to Marsh, saying, "Your work on these old birds & on the many fossil animals of N. America has afforded the best support to the theory of evolution, which has appeared within the last 20 years."

Marsh worked as the Vertebrate Paleontologist for the United States Geological Survey from 1882 to 1892. Thanks to John Wesley Powell, who led the USGS, and Marsh's connections in Washington, Marsh was put in charge of the government's fossil surveys in the late 1880s.

Between 1883 and 1895, Marsh was the President of the National Academy of Sciences.

The best of Marsh's work with dinosaurs came out in 1896. He published two large books: Dinosaurs of North America and Vertebrate Fossils. These books showed his amazing knowledge of the subject.

On December 13, 1897, Marsh received the Cuvier Prize from the French Academy of Sciences. This was a prize of 1,500 French francs.

His Death

Marsh died on March 18, 1899. This was a few years after his big rival, Cope, passed away. He was buried at the Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven, Connecticut.

The Bone Wars

Marsh is also famous for the "Bone Wars" he fought against Edward Drinker Cope. These two men were very competitive. Together, they discovered and described more than 120 new species of dinosaurs.

Marsh first met Cope in Berlin in the winter of 1863. Marsh was thirty-two years old and studying at the University of Berlin. He had two university degrees, while Cope had not gone to formal school past age sixteen. However, Cope had already written 37 scientific papers, compared to Marsh's two. Even though they would become rivals later, they seemed to like each other when they first met. Marsh showed Cope around the city, and they spent several days together. After Cope left Berlin, they kept in touch, sharing their writings, fossils, and photos.

Cope named a fossil Colosteus marshii after Marsh in 1867. Marsh returned the favor, naming Mosasaurus copeanus after Cope in 1869.

In 1868, Marsh visited Cope in Haddonfield, New Jersey. Cope had been finding fossils in quarries there since 1866. These included fossils of Laelaps aquilungis, which he had described as a new species. Before Marsh left, he made deals with the owners of several fossil pits. He asked them to send any new fossils they found to him, not to Cope.

Their rivalry really began when Cope supposedly found out about Marsh's deals. The conflict then moved to the American West. Marsh and Cope started competing to find Eocene mammals in Wyoming. This fight lasted until both men died. Eventually, their competition focused on finding dinosaurs and ancient mammals.

According to Peter Dodson, a paleontologist, "Each man in his own right has left a legacy, and each was a distinguished researcher. But really it seems impossible to say one name without the other. Cope and Marsh." Marsh's names for three dinosaur groups and nineteen dinosaur types (genera) are still used today. Although only three of Cope's named types are still used, he published a record 1,400 scientific papers.

Marsh's Legacy

Marsh named many dinosaur genera (types of dinosaurs), including:

- Allosaurus (1877)

- Ammosaurus (1890)

- Anchisaurus (1885)

- Apatornis (1873)

- Apatosaurus (1877)

- Atlantosaurus (1877)

- Barosaurus (1890)

- Brontosaurus (1879)

- Camptosaurus (1885)

- Ceratops (1888)

- Ceratosaurus (1884)

- Claosaurus (1890)

- Coelurus (1879)

- Coniornis (1893)

- Creosaurus (1878)

- Diplodocus (1878)

- Diracodon (1881)

- Dryosaurus (1894)

- Dryptosaurus (1877)

- Hesperornis (1872)

- Ichthyornis (1873)

- Labrosaurus (1896)

- Laosaurus (1878)

- Lestornis (1876)

- Nanosaurus (1877)

- Nodosaurus (1889)

- Ornithomimus (1890)

- Pleurocoelus (1891)

- Priconodon (1888)

- Stegosaurus (1877)

- Torosaurus (1891)

- Triceratops (1889)

He also named several dinosaur suborders and families. These include:

- Suborders: Ceratopsia (1890), Ceratosauria (1884), Ornithopoda (1881), Stegosauria (1877), and Theropoda (1881).

- Families: Allosauridae (1878), Anchisauridae (1885), Camptosauridae (1885), Ceratopsidae (1890), Ceratosauridae, Coeluridae, Diplodocidae (1884), Dryptosauridae (1890), Nodosauridae (1890), Ornithomimidae (1890), Plateosauridae (1895), and Stegosauridae (1880).

Marsh also named many other specific dinosaur species. Some important ones are Allosaurus fragilis, Triceratops horridus, Stegosaurus stenops, Ornithomimus velox, and Brontosaurus excelsus.

Other scientists have named dinosaurs in honor of Marsh. These include Hoplitosaurus marshi (1901), Iaceornis marshi (2004), Marshosaurus (1976), Othnielia (1977), and Othnielosaurus (2007).

Marsh's fossil finds became the first major collection at Yale's Peabody Museum of Natural History. The museum's Great Hall features the first fossil skeleton of Brontosaurus that Marsh discovered. For a while, it was called Apatosaurus, but a study in 2015 confirmed that Brontosaurus is its own valid type of dinosaur. Other fossils named by Marsh, like Camarasaurus lentus, Nanosaurus agilis, and Camptosaurus dispar, are also displayed in the Peabody fossil hall.

In 1899, Marsh gave his home in New Haven, Connecticut, to Yale University. This house, now called Marsh Hall, is a National Historic Landmark. Marsh Hall is now home to the Yale School of Forestry. The land around it is known as the Marsh Botanical Garden.

Marsh was chosen as a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1877.

Marsh also came up with the Law of brain growth. This law states that during the Tertiary period, many groups of animals showed a gradual increase in brain size. This idea about evolution is still used today because it helps explain and even predict changes.

Before Marsh's work, very few fossils were known in North America. Thanks to George Peabody's generosity, Marsh was able to keep teams of fossil hunters in the field almost constantly from 1870 until he died. The amount of material he collected in 30 years was truly amazing to the scientific world. At the Peabody Museum, Marsh was the first to create full dinosaur skeleton displays. These are now common in many natural history museums around the world.

Mark J. McCarren, who wrote a book about Marsh, summed up his work by saying that Marsh's "contributions to understanding extinct reptiles, birds and mammals are unmatched in the history of paleontology."

Marsh Butte, a mountain in the Grand Canyon, was officially named in his honor in 1906.

See also

In Spanish: Othniel Charles Marsh para niños

In Spanish: Othniel Charles Marsh para niños

- Dinosaur Wars

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |