Sauropods facts for kids

Quick facts for kids SauropodaTemporal range: Upper Triassic – Upper Cretaceous

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

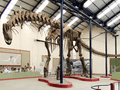

| Mounted skeleton of Apatosaurus Carnegie Museum |

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Superorder: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Infraorder: |

Sauropoda

Marsh, 1878

|

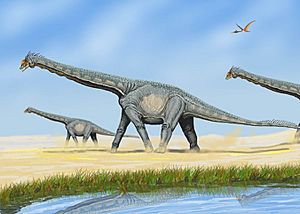

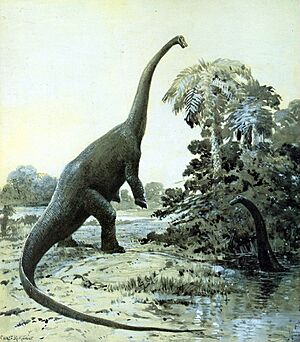

Sauropoda, often called sauropods, were a group of huge, plant-eating dinosaurs. They are famous for their enormous size. Some sauropods were the largest animals to ever walk on land! Well-known sauropods include Brachiosaurus, Diplodocus, and Apatosaurus. (Apatosaurus is the scientific name for what some people used to call Brontosaurus).

Sauropods first appeared in the late Triassic Period. They looked a bit like their close relatives, the prosauropods. By the Late Jurassic (about 150 million years ago), sauropods were found all over the world. Groups like the diplodocids and brachiosaurids were especially common. Later, in the Late Cretaceous, a group called titanosaurs became very widespread. However, like all other non-bird dinosaurs, the titanosaurs died out in the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event. Scientists have found sauropod fossils on every continent, even Antarctica.

The name "Sauropoda" was created by O.C. Marsh in 1878. It comes from ancient Greek words meaning "lizard foot." Finding complete sauropod fossils is rare. Many species, especially the biggest ones, are known only from a few scattered bones. Often, nearly complete skeletons are missing their heads, tail tips, or limbs.

Contents

What Did Sauropods Look Like?

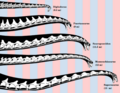

Sauropods were plant-eating dinosaurs. They usually had very long necks and walked on four legs. Their teeth were often shaped like spatulas, wide at the base and narrow at the top. They had tiny heads, huge bodies, and long tails.

Their back legs were thick, straight, and strong. They ended in club-like feet with five toes. Only the inner three or four toes had claws. Their front legs were thinner and ended in pillar-like hands. These hands were built to support their massive weight. Only the thumb had a claw. Many drawings of sauropods are not quite right. They sometimes show sauropods with hooves or too many claws on their feet and hands.

How Big Were Sauropods?

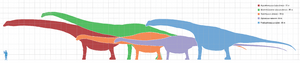

The most amazing thing about sauropods was their size. Even the smaller sauropods, like Europasaurus (which was about 5 to 6 meters, or 20 feet, long), were among the biggest animals in their ecosystem. The only animals that come close in size are huge rorqual whales, like the Blue Whale. But unlike whales, sauropods lived mainly on land.

Sauropod body shapes did not change as much as other dinosaurs. This might be because of how big they were. But they still had many different features. Some, like the diplodocids, had incredibly long tails. They might have cracked these tails like a whip to scare away predators or even make loud sounds. Supersaurus, at about 33 to 34 meters (108 to 112 feet) long, is the longest sauropod known from good fossils. The old record holder, Diplodocus, was also extremely long. A single bone from Amphicoelias fragillimus suggests it might have been 58 meters (190 feet) long. Its backbone would have been much longer than a blue whale's. The longest land animal alive today, the reticulated python, only reaches about 8.7 meters (29 feet).

Other sauropods, like the brachiosaurids, were extremely tall. They had high shoulders and very long necks. Sauroposeidon was probably the tallest, reaching about 18 meters (60 feet) high. The previous record for the longest neck was held by Mamenchisaurus. For comparison, the giraffe, the tallest living animal, is only about 4.8 to 5.5 meters (16 to 18 feet) tall.

Some sauropods were unbelievably heavy. Argentinosaurus was probably the heaviest, weighing 80 to 100 metric tonnes (90 to 110 tons). Other sauropods like Paralititan and Andesaurus were also very large. There is some weak evidence of an even heavier titanosaur, Bruhathkayosaurus, which might have weighed between 175 to 220 tonnes (190 to 240 tons). The largest land animal today, the Savannah elephant, weighs no more than 10 tonnes (11 tons).

Among the smallest sauropods were Ohmdenosaurus (4 meters, or 13 feet, long) and the dwarf titanosaur Magyarosaurus (5.3 meters, or 17 feet, long). The dwarf brachiosaurid Europasaurus was 6.2 meters (20 feet) long as an adult. Its small size was likely due to island dwarfism. This happens when animals get smaller over time because they are stuck on an island with limited food. Another interesting sauropod was Brachytrachelopan. It had an unusually short neck, unlike other sauropods whose necks could be four times longer than their backs.

Sauropod Limbs and Feet

Because they were such massive four-legged animals, sauropods developed special "graviportal" (weight-bearing) limbs. Their back feet were wide and had three claws in most species. Their front feet were very unusual compared to modern large animals like elephants. Instead of spreading out, the bones in a sauropod's front foot were arranged in tall, straight columns. Their finger bones were very small. In advanced sauropods, you wouldn't have seen individual toes on their front feet.

The bones in the front foot were arranged in a half-circle. This is why sauropod front footprints are shaped like a horseshoe. Unlike elephants, sauropods did not have fleshy pads on the bottom of their front feet. The only claw seen on most sauropods was a special thumb claw. Almost all sauropods had this claw, but we don't know what it was for. It was largest in diplodocids and very small in brachiosaurids. Some brachiosaurids might have lost the claw completely.

Titanosaurs may have lost the thumb claw entirely, except for early types. Advanced titanosaurs had no finger bones at all. They walked only on horseshoe-shaped "stumps" made of their foot bones. Footprints from Portugal show that some sauropods (probably brachiosaurids) had small, spiny scales on the bottom and sides of their front feet. These scales left marks in the prints. In titanosaurs, the ends of the foot bones that touched the ground were wide and squared. Some fossils show soft tissue covering this area, suggesting their front feet had some kind of padding.

Scientists like Matthew Bonnan have studied sauropod bones. They found that sauropod leg bones grew in a way that kept their shape the same as they got bigger. This is unusual, as most animals' bones change shape to support more weight. Bonnan suggested this might be like a "stilt-walker" principle. The long legs of adult sauropods allowed them to travel long distances easily without changing how they walked.

Sauropod Tails

The book version of Walking with Dinosaurs suggests that Diplodocus could crack its tail like a stockwhip. This might have made a loud noise for communication.

Air Sacs in Sauropods

Like other saurischian dinosaurs (including birds and other theropods), sauropods had a system of air sacs. We know this because their vertebrae (backbones) have hollow spaces and indentations. These hollow, air-filled bones are a key feature of all sauropods.

Scientists noticed the bird-like hollow bones in sauropods early on. In fact, one sauropod fossil found in the 1800s was first thought to be a pterosaur (a flying reptile) because of these hollow bones.

Sauropod Armor

Some sauropods had armor. There were types with spines on their backs, like Agustinia. Some had small clubs on their tails, like Shunosaurus. Several titanosaurs, such as Saltasaurus and Ampelosaurus, had small bony plates called osteoderms covering parts of their bodies.

Sauropod Behavior and Life

Herding and Caring for Young

Many fossil clues, from bone beds (places where many bones are found together) and trackways (fossil footprints), show that sauropods lived in herds. However, the way these herds were organized was different for various species. Some bone beds, like one from the Middle Jurassic in Argentina, suggest herds had mixed ages, with young and adult sauropods together.

But other fossil sites and trackways show that many sauropod species traveled in herds separated by age. Young sauropods formed their own herds, separate from adults. This kind of age-separated herding has been found in species like Alamosaurus and Bellusaurus.

Scientists have tried to figure out why sauropods often formed separate herds. Studies of tiny marks on their teeth show that young sauropods ate different foods than adults. This suggests that young and old sauropods had different ways of finding food. So, herding together might not have been as helpful as herding separately. The huge size difference between young and adult sauropods might also have played a role in their different feeding and herding habits.

Since young and adult sauropods separated soon after hatching, some scientists believe that species with age-separated herds did not provide much parental care, if any. On the other hand, scientists who studied age-mixed sauropod herds think these species might have cared for their young for a long time before they grew up. We don't yet know exactly how herding behavior varied among different sauropod groups. More fossil evidence is needed to understand these patterns.

Could Sauropods Stand on Their Hind Legs?

Since the early days of studying sauropods, scientists have wondered if they could stand up on their hind legs. They might have used their tail as a third "leg" to form a tripod. A skeleton of the diplodocid Barosaurus lentus at the American Museum of Natural History shows it standing in this way.

In 2005, scientists Rothschild and Molnar thought that if sauropods stood on two legs, their front limb bones would show signs of stress. But after looking at many sauropod skeletons, they found no such signs.

However, Heinrich Mallison (in 2009) was the first to study if different sauropods could physically stand in a tripod stance. Mallison found that some features thought to help with rearing actually didn't. For example, titanosaurs had a very flexible backbone. This would have made them less stable when standing on two legs and put more strain on their muscles. It's also unlikely that brachiosaurids could stand on their hind legs. Their center of gravity was much further forward, making such a stance unstable.

Diplodocids, however, seem to have been well-suited for standing on their hind legs. Their center of mass was right over their hips, giving them better balance on two legs. Diplodocids also had the most flexible necks among sauropods, strong hip muscles, and tail bones shaped to bear weight when touching the ground. Mallison concluded that diplodocids were even better at rearing than elephants, which sometimes do it in the wild. He also argued that stress fractures in wild animals don't usually come from everyday activities like feeding.

Head and Neck Position

There is a debate about whether sauropods held their heads mostly straight out or pointing upwards. Some scientists questioned if their long necks were used to browse high trees. They calculated the energy needed to pump blood up to the head if it was held upright. These calculations suggested it would take about half of the sauropod's energy intake. Also, to get blood to a high head, their hearts would need to be 15 times bigger than whales of similar size.

This suggests it was more likely that their long necks were usually held horizontally. This would let them eat plants over a very wide area without moving their huge bodies. This would save a lot of energy for animals weighing 30 to 40 tons. Supporting this idea, reconstructions of Diplodocus and Apatosaurus necks show them as mostly straight. Their heads would be in a "neutral" position when close to the ground.

However, research on living animals suggests that sauropod heads were held in an upright S-shaped curve. Some scientists say that using bones to guess "neutral head postures" might not be accurate. If applied to living animals, it would suggest they also hold their heads horizontally, even though they don't.

Sauropod Footprints and Movement

Sauropod trackways (paths of fossil footprints) are found in many places on most continents. These footprints have helped scientists understand more about sauropods, including their foot anatomy. Generally, front foot prints are much smaller than hind foot prints and are often crescent-shaped. Sometimes, footprints show traces of claws, helping confirm which sauropod groups lost claws or even toes on their front feet.

Sauropod trackways are usually put into three groups based on the distance between opposite feet: narrow, medium, and wide. The trackway width can help figure out how wide sauropods held their legs and how they walked. A 2004 study found a general pattern among advanced sauropods. Each sauropod family had certain trackway widths. Most sauropods, except titanosaurs, had narrow-set limbs. Their front foot prints often showed strong marks from the large thumb claw.

Medium-width trackways with claw marks on the front feet probably belong to brachiosaurids and other early titanosauriformes. These groups were developing wider-set limbs but still had their claws. Early true titanosaurs also kept their front foot claw but had developed fully wide-set limbs. Wide-set limbs were kept by advanced titanosaurs. Their trackways show wide spacing and no claws or toes on the front feet.

Why Did Sauropods Get So Big?

Scientists have tried to answer why sauropods became so huge. They reached gigantic sizes early in their evolution, right from the first true sauropods in the late Triassic Period. According to Kenneth Carpenter, whatever made them grow so big must have been present from the very beginning of the group.

Studies of large plant-eating mammals, like elephants, show that bigger size helps them digest food more efficiently. Larger animals have longer digestive systems. Food stays in digestion for much longer, allowing big animals to survive on lower-quality food. This is especially true for animals with many "fermentation chambers" in their intestines. These chambers allow tiny living things to break down plant material, helping digestion.

Throughout their history, sauropod dinosaurs mostly lived in dry areas with seasons. This meant food quality dropped during the dry season. The environment of most giant Late Jurassic sauropods, like Amphicoelias, was like a savanna. This is similar to the dry places where modern giant plant-eaters live. This supports the idea that poor-quality food in dry environments encourages the evolution of giant plant-eaters. Carpenter argued that other benefits of large size, like being safer from predators, using less energy, and living longer, were probably secondary. He believed sauropods grew large mainly to process food more efficiently.

How Were Sauropods Discovered?

The first scattered fossil remains now known as sauropods were found in England. At first, scientists thought they were many different things. Their connection to other dinosaurs was not understood until much later.

The first sauropod fossil described by science was a single tooth. It was called Rutellum implicatum by Edward Lhuyd in 1699. But at that time, no one knew it was from a giant prehistoric reptile. Dinosaurs would not be recognized as a group for over 100 years.

Richard Owen published the first modern scientific description of sauropods in 1841. He named Cetiosaurus and Cardiodon. Cardiodon was only known from two unusual, heart-shaped teeth. Owen couldn't identify it beyond knowing it was from a large, unknown reptile. Cetiosaurus was known from slightly better, but still scattered, remains. Owen thought Cetiosaurus was a giant marine reptile related to modern crocodiles. That's why its name means "whale lizard." A year later, when Owen created the name Dinosauria, he did not include Cetiosaurus and Cardiodon in that group.

In 1850, Gideon Mantell realized that several bones Owen had called Cetiosaurus were actually from a dinosaur. Mantell noticed that the leg bones had a hollow space inside, which is typical of land animals. He named these specimens a new genus called Pelorosaurus and grouped it with the dinosaurs. However, Mantell still didn't see the connection to Cetiosaurus.

The next sauropod fossil to be described and wrongly identified was a set of hip vertebrae. Harry Seeley described them in 1870. Seeley found that the vertebrae were very light for their size and had openings for air sacs. At the time, such air sacs were only known in birds and pterosaurs. So, Seeley thought the vertebrae came from a pterosaur. He named the new genus Ornithopsis, meaning "bird face."

When more complete Cetiosaurus specimens were described by Phillips in 1871, he finally recognized the animal as a dinosaur related to Pelorosaurus. But it wasn't until new, nearly complete sauropod skeletons were found in the United States (Apatosaurus and Camarasaurus) later that year that scientists got a full picture of sauropods. John A. Ryder made an early reconstruction of a complete sauropod skeleton based on Camarasaurus. However, many features were still not quite right or complete compared to later discoveries. Also in 1877, Richard Lydekker named another relative of Cetiosaurus, Titanosaurus, based on a single vertebra.

In 1878, the most complete sauropod found yet was described by Othniel Charles Marsh. He named it Diplodocus. With this find, Marsh also created a new group to hold Diplodocus, Cetiosaurus, and their growing list of relatives. He wanted to separate them from other major dinosaur groups. Marsh named this group Sauropoda, or "lizard feet."

Images for kids

-

Sauropod tracks near Rovereto, Italy

-

Sauropod tracks at Serras de Aire e Candeeiros Natural Park, Portugal

-

Reconstructed skeleton used to estimate speed, Museo Municipal Carmen Funes, Plaza Huincul, Argentina

-

Argentinosaurus - one of the largest dinosaurs known today

-

Several macronarian sauropods; from left to right, Camarasaurus, Brachiosaurus, Giraffatitan, and Euhelopus.

See also

In Spanish: Sauropoda para niños

In Spanish: Sauropoda para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |