Gideon Mantell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Gideon Mantell

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 3 February 1790 Lewes, Sussex, England

|

| Died | 10 November 1852 (aged 62) London, England

|

| Occupation | Surgeon, palaeontologist |

| Known for | Describing Iguanodon |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Ann Mantell |

| Relatives | Walter Mantell (son) |

| Awards | Wollaston Medal (1835) Royal Medal (1849) |

Gideon Algernon Mantell (born February 3, 1790 – died November 10, 1852) was a British doctor, geologist, and palaeontologist. He was one of the first people to study dinosaurs scientifically. In 1822, he found the first fossil teeth of a dinosaur called Iguanodon. Later, he found more of its skeleton. Mantell's work on the Cretaceous period in southern England was also very important.

Contents

Early Life and Medical Training

Gideon Mantell was born in Lewes, England. He was the fifth of seven children. His father, Thomas Mantell, was a shoemaker. Gideon grew up in a small house with his two sisters and four brothers.

Even as a young boy, Gideon loved geology, which is the study of Earth's rocks and history. He explored local pits and quarries. There, he found ammonites (ancient shell creatures), sea urchin shells, fish bones, coral, and old animal remains.

Gideon's family followed the Methodist church. Because of this, he could not attend the local free schools. These schools were only for children from Anglican families. So, Gideon first learned to read and write from an old woman at a small school. After she died, he was taught by John Button, a political thinker who shared ideas with Gideon's father. Gideon studied with Button for two years. Then, he went to his uncle, a Baptist minister, in Swindon for more private study.

Gideon returned to Lewes when he was 15. A local political leader helped him get an apprenticeship with a surgeon named James Moore. For five years, Gideon lived with Moore and learned about medicine. He started by cleaning bottles and sorting medicines. Soon, he learned to make pills and other medical products. He also delivered medicines, managed accounts, and even pulled teeth for patients.

In 1807, Gideon's father died. He left Gideon some money for his education. As his apprenticeship ended, Gideon prepared for medical school. He taught himself human anatomy, which is the study of the body's structure. He even drew detailed pictures of bones. Gideon then went to London for formal medical training. In 1811, he became a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons. He also received a certificate to work as a midwife, helping women give birth.

Mantell went back to Lewes and became partners with his old teacher, James Moore. It was a very busy time because of widespread illnesses like cholera and smallpox. Mantell often saw more than 50 patients a day. He also helped deliver 200 to 300 babies each year. He once said he had to stay awake for "six or seven nights in a row" because of his work. He also helped his practice earn more money.

Even with his busy medical work, Mantell spent his free time on his passion: geology. He often worked late into the night. He identified fossils he found in the marl pits at Hamsey. In 1813, Mantell started writing to James Sowerby. Sowerby was a naturalist who studied fossil shells. Mantell sent him many fossils. To thank him, Sowerby named a type of ammonite Ammonites mantelli. In December, Mantell was chosen as a fellow of the Linnean Society of London. Two years later, he published his first scientific paper about the fossils found near Lewes.

In 1816, Gideon married Mary Ann Woodhouse. She was 20 years old. They married on May 4 at St. Marylebone Church. That year, he bought his own medical practice. He also started working at the Royal Artillery Hospital in Ringmer, Lewes.

Discovering Ancient Life

Gideon Mantell was inspired by Mary Anning. She had found a huge fossil animal that looked like a crocodile. It was later called an ichthyosaur. Mantell became very interested in studying the fossilized animals and plants in his own area.

The fossils he first collected were from the chalk hills in Sussex. These fossils were from the Upper Cretaceous period and were from ocean animals. But by 1819, Mantell started finding fossils from a quarry near Cuckfield. These new fossils were from land and freshwater animals. This was exciting because all other known fossils from the Cretaceous period in England were from the ocean. He named the new rock layers the Strata of Tilgate Forest. This area was later shown to be from the Lower Cretaceous period.

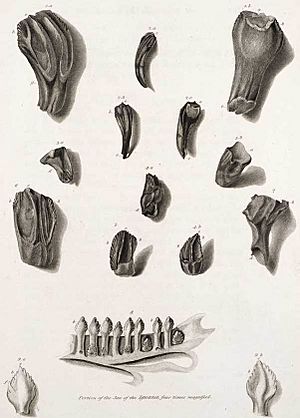

By 1820, Mantell was finding very large bones at Cuckfield. They were even bigger than bones found by William Buckland in Oxfordshire. Then, in 1822, his wife found several large teeth. Mantell could not figure out what animal they belonged to.

In 1821, Mantell planned his next book about the geology of Sussex. It was very popular. Even King George IV ordered four copies! Mantell was very encouraged. He showed the teeth to other scientists. But they thought the teeth belonged to a fish or a mammal. They also thought the teeth were from a more recent rock layer. The famous French anatomist, Georges Cuvier, even said the teeth were from a rhinoceros.

However, Cuvier later had doubts. He realized the teeth were "something quite different." But this new idea did not reach Britain. Mantell was still laughed at for his mistake. Mantell was sure the teeth were from the Mesozoic era (the age of dinosaurs). He finally realized they looked like the teeth of an iguana, but they were 20 times bigger! He guessed that the animal must have been at least 60 feet (18 meters) long.

Getting Recognition

Mantell tried hard to convince other scientists that his fossils were from the Mesozoic era. He carefully studied the rock layers. William Buckland famously disagreed, saying the teeth were from fish.

But in 1825, Mantell was proven right. The only question was what to name his new reptile. He first thought of "Iguana-saurus." But then he got a letter from William Daniel Conybeare. Conybeare suggested "Iguanoides" or "Iguanodon" because "Iguana-saurus" was too similar to the living iguana. Mantell liked this advice and named his creature Iguanodon.

Years later, Mantell found enough fossils to show that the dinosaur's front legs were much shorter than its back legs. This proved they were not built like a mammal, as Sir Richard Owen had claimed. Mantell also showed that many fossil vertebrae (backbones) that Owen thought were from different species all belonged to Iguanodon. Mantell also named another new dinosaur called Hylaeosaurus. Because of his discoveries, he became a leading expert on ancient reptiles.

Later Years and Challenges

In 1833, Mantell moved to Brighton. But his medical practice did not do well there. He almost ran out of money. The town council helped by turning his house into a museum. He gave talks there, which were published in 1838 as The wonders of geology. However, the museum eventually failed because Mantell often let people in for free.

With money problems, Mantell offered to sell his fossil collection to the British Museum in 1838. He asked for £5,000 but accepted their offer of £4,000. He then moved to Clapham Common in South London and continued working as a doctor.

Mary Mantell, Gideon's wife, left him in 1839. That same year, his son Walter moved to New Zealand. Walter later sent his father important fossils from New Zealand. Gideon's daughter, Hannah, died in 1840.

In 1841, Mantell started having problems with his spine. He was diagnosed with scoliosis, a condition where the spine curves. This might have been made worse by a carriage accident. Even though he was bent, crippled, and in constant pain, he kept working with fossilized reptiles. He published many scientific books and papers until he died. He moved to Pimlico in 1844.

Death and Lasting Impact

On November 10, 1852, Gideon Mantell fell into a coma and died that afternoon. After his death, doctors found he had been suffering from scoliosis. A part of his spine was removed and kept at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. It stayed there until 1969 when it was removed due to lack of space.

Mantell's old surgery building in Clapham Common is now a dental office.

When he died, Mantell was known for discovering 4 out of the 5 types of dinosaurs known at that time.

In 2000, a monument was unveiled at Whiteman's Green, Cuckfield. It honors Mantell's discovery and his contributions to palaeontology. This monument marks the place where the Iguanodon fossils Mantell first described were found.

He is buried at West Norwood Cemetery in a special stone coffin. It looks like a temple from ancient Egypt. It's interesting that the name ammonite (a fossil he studied) comes from the Egyptian god Amun, whose temple inspired his tomb.

Works by Mantell

Mantell wrote many books and scientific papers. Here are some of his important works:

- The Fossils of the South Downs (1822). This was his first book. His wife drew the pictures for it.

- Illustrations of the Geology of Sussex (1827). This book included pictures and descriptions of fossils from Tilgate Forest.

- The Geological Age of Reptiles (1831).

- The Geology of the South-East of England (1833). This book had colored maps and many pictures.

- Thoughts on a Pebble (1836).

- The Wonders of Geology (1838). This was one of his most important works. It was based on talks he gave in Brighton. His wife also drew many of the colored pictures for this book.

- The Medals of Creation (1844).

- Thoughts on Animalcules (1846). This book was about tiny creatures seen through a microscope.

- Geological Excursions round the Isle of Wight and along the adjacent Coast of Dorsetshire (1847).

- Pictorial Atlas of Fossil Remains (1850).

- Petrifactions and their teachings (1851).

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Gideon Mantell para niños

In Spanish: Gideon Mantell para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |