International Whaling Commission facts for kids

| Formation | 2 December 1946 |

|---|---|

| Type | Specialised regional fishery management organization |

| Legal status | International organization |

| Purpose | "provide for the proper conservation of whale stocks and thus make possible the orderly development of the whaling industry" |

| Headquarters | Impington, United Kingdom |

|

Membership (2020)

|

88 countries |

|

Executive Secretary

|

Rebecca Lent |

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) is a special group that manages whale populations around the world. It was created in 1946 by the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW). Its main goal is to make sure whales are protected and that any whaling is done in an organized way.

The IWC makes rules for whaling. These rules include protecting certain whale species completely. They also set aside special areas as whale sanctuaries. The IWC decides how many whales can be caught and what size they should be. They also set open and closed times and places for whaling. It is against the rules to catch baby whales or mothers with their calves.

The IWC also collects information about whale catches. They gather statistics and biological records. They are very involved in whale research. This includes funding studies, sharing scientific results, and looking into how whaling is done.

In 2018, the IWC members made the "Florianópolis Declaration." They decided that the IWC's main purpose is to protect whales forever. They want all whale populations to grow back to the numbers they had before people started hunting them a lot. After this, Japan announced on December 26, 2018, that it was leaving the IWC. Japan said the IWC was not promoting sustainable hunting, which was one of its original goals. Japan then started commercial whaling again in its own waters in July 2019. However, it stopped whaling in the Southern Hemisphere.

Contents

How the IWC Works

The IWC was set up by countries that agreed to work together. It is the main group that can make rules under the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling. This agreement was signed in 1946. Its goal is to protect whales and allow whaling to happen in an organized way.

The IWC regularly checks and updates its rules. These rules control whaling by:

- Protecting certain whale species.

- Creating safe areas for whales.

- Setting limits on how many whales can be caught.

- Deciding when and where whaling can happen.

- Controlling whaling methods and equipment.

The IWC's rules are based on scientific findings.

The IWC's main office is in Impington, near Cambridge, England. The IWC publishes research, reports, and meeting schedules.

The IWC has three main groups:

- The Scientific Committee.

- The Conservation Committee.

- The Finance and Administration Committee.

A Technical Committee also exists, but it does not meet anymore.

Who Can Join the IWC?

Countries that do not hunt whales can also join the IWC. Since 2001, the number of IWC members has almost doubled. As of February 2024, there were 88 member countries.

Some of the current members include: Australia, Brazil, China, Denmark, France, Germany, Iceland, India, Japan (until 2019), Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Russia, South Africa, Sweden, United Kingdom, and United States.

IWC Meetings

Since 2012, the IWC has held its main meetings every two years, usually in September or October. Each member country sends one voting representative, called a Commissioner. They can bring experts and advisors with them.

These meetings can be very divided. Countries that support whaling often disagree with countries that want to protect whales. Other groups, like non-member countries and environmental organizations, can also attend as observers.

Even though the main meetings are every two years, the Scientific Committee still meets every year. This gives everyone time to read the Scientific Committee's reports before the main meeting.

Whaling Pause of 1982

In the 1970s, a global movement to protect whales began. In 1972, a United Nations meeting suggested a ten-year pause on commercial whaling. This was to help whale populations recover. Reports in 1977 and 1981 showed that many whale species were in danger.

At the same time, more countries that did not hunt whales joined the IWC. They eventually became the majority. Some countries that used to hunt many whales, like the United States, started to strongly support protecting them. These countries wanted the IWC to change its rules based on new scientific information about whales.

On July 23, 1982, the IWC members voted to put a pause on commercial whaling. This decision needed a three-quarters majority, and it passed with 25 votes for, 7 against, and 5 countries not voting.

The rule said that from 1986 onwards, no whales could be caught for commercial purposes. This rule would be reviewed based on scientific advice. By 1990, the IWC would check how this decision affected whale populations. They would then decide if they needed to change the rule or set new catch limits.

Japan, Norway, Peru, and the Soviet Union (now Russia) formally disagreed with this decision. They said it was not based on advice from the Scientific Committee. Japan and Peru later withdrew their objections. In 2002, Iceland rejoined the IWC with a special condition about the pause, but many IWC members do not agree with this condition.

What the Pause Allows

The pause only applies to commercial whaling. Whaling for scientific research and for the needs of indigenous (native) communities is still allowed under the IWC rules. However, some environmental groups say that "research whaling" is sometimes just a way to continue commercial whaling.

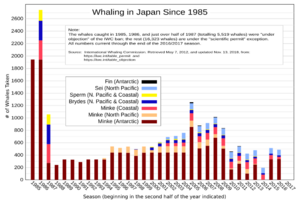

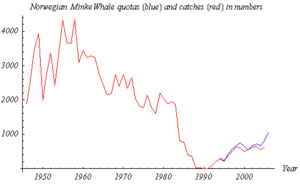

Since 1994, Norway has been whaling commercially because it formally objected to the pause. Iceland also started commercial hunting in September 2006. Since 1986, Japan hunted whales for scientific research. The U.S. and some other countries hunt whales for indigenous communities.

Countries that are against whaling often say that Japan's scientific whaling is actually commercial whaling in disguise. The Japanese government says that IWC rules allow whale meat from scientific whaling to be used, so it should not go to waste.

In May 1994, the IWC also voted to create the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary. This is a huge area of about 11.8 million square miles (30.6 million square kilometers) where whales are protected. The vote to create this sanctuary passed with 23 votes for, 1 against (Japan), and 6 countries not voting.

Florianópolis Declaration (2018)

On September 13, 2018, IWC members met in Florianópolis, Brazil. They discussed a proposal from Japan to restart commercial whaling, but they rejected it.

In the "Florianópolis Declaration," the IWC members decided that their main goal is to protect whales. They agreed to protect these marine mammals forever. They also want all whale populations to return to their numbers before large-scale whaling began. The declaration also stated that using deadly methods for research is not needed. This agreement was supported by 40 countries, while 27 countries that supported whaling voted against it. Under this declaration, limited hunting by some indigenous communities is still allowed.

On December 26, 2018, Japan announced it was leaving the IWC. Japan said the IWC did not promote sustainable hunting, which was one of its original goals. Japanese officials said they would start commercial hunting again in their own waters and special economic zones from July 2019. However, they stopped whaling in the Antarctic Ocean, the northwest Pacific Ocean, and the Australian Whale Sanctuary.

IWC Rules and Challenges

The IWC is a group that countries join voluntarily. It does not have a way to force countries to follow its rules or punish them.

- First, any member country can simply leave the IWC if they want to.

- Second, a member country can choose not to follow a specific IWC rule. They can do this by formally disagreeing with it within 90 days of the rule being made. This is common in international agreements.

- Third, the IWC cannot punish countries that do not follow its decisions.

International Observer Scheme

In 1971, Australia and South Africa agreed to send observers to each other's whaling stations. This was to make sure they followed IWC rules. Similar agreements were made for other areas. These observers helped improve the quality of reported whale catch data.

Politics and Disagreements

There has been a lot of disagreement within the IWC. Some countries want to restart whaling, while others want to protect every whale. This has put a lot of pressure on the IWC. Experts believe that changes to the IWC are needed. They think that whaling for human use will continue, whether under new IWC rules or other agreements.

Some conservation groups argue that the IWC should focus more on other threats to whales. These threats include whales being hit by ships, pollution, and climate change. They say the IWC cannot focus on these issues until the disagreements about hunting are solved.

Accusations of Politics in Science

Countries that support whaling accuse the IWC of making decisions based on "political and emotional" reasons, not just science. They point out that the IWC bans all commercial whaling. However, its own Scientific Committee has said since 1991 that some whale species could be hunted sustainably. These countries argue that the IWC has changed its original purpose. They say it is trying to completely protect whales from being hunted for commercial reasons.

Canada left the IWC after the pause was voted in. It said the ban did not fit with rules the IWC had just made to allow safe levels of hunting.

After the 1986 pause, the Scientific Committee studied whale populations. In 1991, they reported that there were many minke whales in different oceans. They suggested that about 2,000 minke whales could be caught each year without harming the population. But the IWC decided to keep the ban on whaling. They said that the methods for deciding safe catch limits still needed more evaluation.

In 1991, the IWC adopted a computer program called the Revised Management Procedure (RMP). This program helps decide how many whales can be caught safely. Even though the RMP showed that some catches could be allowed, the pause was not lifted. The IWC said they needed to agree on how to collect data and how to monitor whaling.

The IWC adopted the RMP in 1994. But they decided not to use it until a system for inspection and control was developed. This system, with the RMP, is called the Revised Management Scheme (RMS). Since then, member countries have found it very hard to agree on the RMS.

Australia is the only IWC member that has officially said it is against any RMS. Anti-whaling groups like Sea Shepherd and Greenpeace are also generally against the RMS.

Ray Gambell, who was the Secretary of the IWC, agreed that some commercial whaling could happen without harming minke whale populations. In June 1993, the head of the Scientific Committee, Dr. Philip Hammond, resigned. He felt that the Scientific Committee's advice was being ignored. That same year, Norway became the only country to restart commercial whaling. They did this because they had formally disagreed with the pause.

IWC Membership and Influence

The IWC's original goal was to protect whale populations for the future. At first, only 15 countries that hunted whales were members. But since the late 1970s, many countries that had never hunted whales joined the IWC. Some of these countries, like Switzerland and Mongolia, don't even have coastlines!

This change started with Peter Scott, who was head of the World Wide Fund for Nature. He called the IWC a "butchers' club." He worked with environmental groups to change who was in the IWC. This helped get enough votes to put the pause on commercial whaling in 1986. This led to the first accusations of countries trying to buy votes in the IWC.

Since the pause was adopted, support for it has dropped. It went from a 75% majority to about 50-50. Many countries that were first brought in by the anti-whaling side now vote with the pro-whaling side. (A 75% majority is needed to end the pause.)

Anti-whaling groups and some governments claim that Japan has offered aid to poorer countries. They say this was in return for these countries joining the IWC and supporting Japan's views on whaling. Japan says this accusation is politically motivated. Japan gives aid to many countries, including those against whaling.

Japan has given a lot of money in aid to countries like Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, and Grenada. Countries in the Caribbean have often voted with Japan in IWC votes since 2001. Pacific countries' votes can change because they are influenced by both pro-whaling Japan and anti-whaling New Zealand and Australia. Greenpeace says that Japan's aid and these countries' voting patterns are connected.

Both sides accuse each other of using unfair methods to get countries to join the IWC and support their side. Edwin Snagg, an IWC commissioner, said that smaller, less developed countries feel offended when people think they can be easily bought. Also, no developing countries support an anti-whaling stance.

The BBC reported that some countries joining the European Union were told it would be a good idea to join the IWC. Some activists believe that countries like Britain, France, and Germany should get all EU members to join the IWC.

Both pro- and anti-whaling countries say their efforts are just about convincing others based on their beliefs. Anti-whaling groups argue that science is not clear enough to restart commercial whaling. They also say that whale welfare is important, not just conservation. Pro-whaling countries argue that the public's anti-whaling views are often based on wrong information. For example, many people incorrectly believe that all whale species are endangered.

Japan argues that coastal countries have an interest in protecting their fish stocks, which whales might threaten. Japan also says that the anti-whaling side is using conservation as an excuse for their opposition to whaling.

At the London IWC meeting in 2001, New Zealand accused Japan of buying votes. The Japanese delegate denied this. He said Japan gives aid to over 150 nations, including strong anti-whaling ones. He also said that Caribbean countries naturally supported pro-whaling ideas because they hunt smaller whales themselves.

Anti-whaling groups point to statements from officials. Atherton Martin, Dominica's former Environment Minister, said Japan made it clear that if countries did not vote for them, they would reconsider aid. Greenpeace also quoted a Tongan politician saying Japan linked whale votes to aid. Lester Bird, prime minister of Antigua and Barbuda, said he would support Japan if whales were not endangered, especially if it meant getting assistance.

In a 2001 interview, a Japanese official called minke whales "cockroaches of the sea." He also said that because Japan does not have military power, it uses diplomacy and aid to get support for its whaling position. Billions of yen have gone to countries that joined the IWC from both pro- and anti-whaling sides.

In Japan, some media outlets argue that countries against commercial whaling should not be in the IWC. They say the anti-whaling side has changed the IWC's purpose. They also point out that wealthy countries lead the anti-whaling group. They accuse the anti-whaling side of using conservation as a cover for their opposition to whaling. Since 2000, 29 new countries have joined the IWC: 18 pro-whaling and 11 anti-whaling. Japan notes that major anti-whaling countries like the U.S., Australia, UK, and New Zealand also give aid to poorer IWC countries. They say these countries have more influence than Japan alone.

Japan wants secret voting at IWC meetings. This would make it harder to accuse Japan of vote-buying. It would also reduce the influence of the anti-whaling group. Anti-whaling governments are against secret voting. They say it is not common in other international groups and would make things less clear. However, some commissioners argue that it is unfair to demand open voting in the IWC when other similar groups use secret ballots.

The Role of the United States

The United States has often acted on its own to support IWC decisions. This has helped make IWC decisions effective, especially for smaller whaling countries. Countries that support whaling often see the U.S. actions as "bullying." Environmentalists, however, often praise the U.S. approach.

The U.S. passed laws to support the IWC's rules. The Pelly Amendment in 1971 allows the U.S. President to ban fishing products from countries that do not follow international fishing rules, including the IWC's. The U.S. has used this threat many times. For example, in 1974, pressure from the U.S. helped Japan and the Soviet Union follow whaling limits. In 1978, Chile, South Korea, and Peru joined the IWC after U.S. threats.

These measures were made stronger by the Packwood-Magnuson Amendment in 1979. This law says that if a country harms the IWC's work, the U.S. must cut that country's fishing rights in U.S. waters by at least 50%. In 1980, the threat of this law made South Korea agree to IWC rules. In 1981, Republic of China (Taiwan) completely banned whaling because of similar pressure. Without U.S. support, the 1986 pause might not have been as strong. Countries like Iceland, Japan, Norway, and the Soviet Union might have continued commercial whaling.

The North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission

The pause on commercial whaling caused Iceland to leave the IWC in protest. Japan and Norway also threatened to leave. In April 1992, the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO) was created. It was formed by the Faroe Islands, Greenland, Iceland, and Norway. This group was created partly because these countries were unhappy with the IWC's zero-catch rule. While NAMMCO does not directly go against IWC rules, it shows a challenge to the IWC's authority.

Images for kids

See also

- Institute of Cetacean Research (Japan)

- Whaling in Australia

- Whaling in Iceland

- Whaling in Japan

- Whaling in Norway

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |