Crossword facts for kids

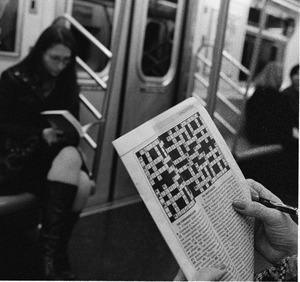

A crossword is a fun puzzle that uses words. You usually find them in newspapers, magazines, and books. You can also play crosswords online or on mobile apps!

The very first crossword puzzle was made by Arthur Wynne, a journalist from Liverpool. It appeared in the New York World newspaper on December 21, 1913. Today, many newspapers and magazines, like New York Times, are famous for their crosswords. A new puzzle often comes out every day or in every new issue. The solution is usually found the next day or in a later issue.

Contents

How to Play Crosswords

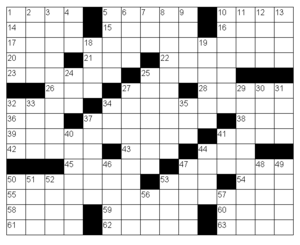

A crossword puzzle has a grid of black and white squares. You fill in words or phrases, called "entries," both horizontally ("across") and vertically ("down"). You use clues to figure out the words. Each white square usually holds one letter. Black squares separate the different words. The first white square of each word has a number. This number matches a clue in the list.

There are different kinds of crosswords. Straight or Quick crosswords use simple definitions. This means the clues describe the answer directly. Some crosswords, called cryptic crosswords, use riddles and word play. These are usually much harder than straight crosswords.

Example Crossword Puzzle

Here is a small example of a British-style straight crossword:

| 1 | 2 | |||

| 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 |

Across Clues

1. Sheep sound (3 letters)

3. Neither liquid nor gas (5 letters)

5. Humour (3 letters)

Down Clues

1. Road passenger transport (3 letters)

2. Permit (5 letters)

4. Short for "Dorothy" (3 letters)

The solution (answer) to this crossword is:

| 1B | 9A | 2A | . | . |

| 9U | . | 9L | . | . |

| 3S | 9O | 9L | 9I | 4D |

| . | . | 9O | . | 9O |

| . | . | 5W | 9I | 9T |

Different Types of Crosswords

Crossword grids look a bit different depending on where you are. In North America, grids usually have large white areas. Every letter you fill in is part of both an "across" word and a "down" word. Also, answers usually have at least three letters. Black squares take up about one-sixth of the grid.

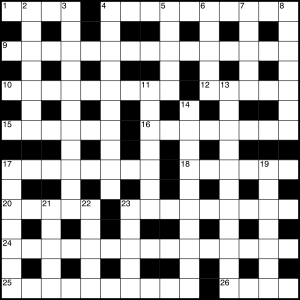

In places like Britain, South Africa, and Australia, grids look more like a lattice. They have more black squares (about 25%). This means about half the letters in an answer might only be part of one word (either across or down).

Many puzzles also have rotational symmetry. This means the pattern of black and white squares looks the same if you turn the paper upside down.

Crossword Sizes and Difficulty

Puzzles often come in standard sizes. For example, many weekday newspaper puzzles, like the New York Times crossword, are 15x15 squares. Weekend puzzles can be larger, like 21x21 or 25x25.

The New York Times puzzles also get harder throughout the week. Monday puzzles are the easiest, and they get tougher until Saturday. Their big Sunday puzzle is usually as hard as a Thursday puzzle. Because of this, people in the U.S. often describe a puzzle's difficulty by the day of the week. An easy puzzle might be called a "Monday," and a really hard one a "Saturday."

Clues are usually listed outside the grid, separated into "across" and "down" lists. The first square of each answer has a number that matches its clue. For example, the answer to "17 Down" starts in the square numbered "17" and goes downwards.

Cryptic Crosswords

In cryptic crosswords, the clues are puzzles themselves! They usually have two parts: a definition and some kind of word play. You need to read cryptic clues in two ways. First, there's the obvious meaning. Second, there's a hidden meaning. This hidden meaning could be a double definition, an anagram (rearranged letters), a homophone (words that sound alike), or words spelled backwards.

Solving cryptic crosswords takes practice because you need to learn how to understand the different types of clues. They are very popular in Great Britain and many other Commonwealth countries. The first strictly cryptic crosswords appeared in the 1920s, thanks to Edward Powys Mathers.

Other Cool Crossword Types

There are many other interesting crossword variations!

Cipher Crosswords

Imagine a crossword where numbers are clues instead of words! In a cipher crossword, each white square has a number from 1 to 26. Each number stands for a letter of the alphabet. If two squares have the same number, they must have the same letter. No two numbers stand for the same letter. You have to figure out which letter each number represents. Usually, one letter is given to help you start.

Diagramless Crosswords

A diagramless crossword is tricky because it doesn't show you the grid! You get the overall size, but you don't know where the black squares or clue numbers are. You have to solve the clues and then figure out how to fit the answers together to build the grid yourself.

Fill-in Crosswords

In a fill-in crossword, you get the grid and a list of all the words you need to use. The challenge is to figure out where each word goes in the grid. There are no specific clues for each word. These puzzles often have longer words, which can make them a bit easier to solve because there are fewer ways they can connect.

Cross-figures

A cross-figure, or crossnumber, is like a crossword but with numbers instead of words. The clues are usually math problems, or they might be general knowledge questions where the answer is a number or a year.

Acrostic Puzzles

An acrostic puzzle has two parts. First, you get clues with numbered blanks for the letters of the answer. Second, there's a long series of numbered blanks and spaces. When you solve the clues, the answers fit into these blanks. The cool part is that the first letter of each correct clue answer, read in order, spells out the author of a hidden quote and the title of their work!

Arroword

The arroword is a crossword type that doesn't have as many black squares. Instead, it has arrows inside the grid. The clues are placed right next to these arrows, pointing to where the answer should go. It's very popular in many European countries, especially in Scandinavia, where it's thought to have started.

Interesting Facts About Crosswords

- On December 21, 1913, Arthur Wynne published a "word-cross" puzzle in the New York World. This is often called the first modern crossword puzzle. An illustrator later changed "word-cross" to "cross-word."

- The word "crossword" first appeared in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1933.

- The first book of crossword puzzles came out in 1924 from Simon & Schuster. It was a huge hit and made crosswords super popular!

- The New York Times started publishing a crossword puzzle on February 15, 1942. They thought it would be a good way to distract people from the serious news of World War II.

- According to Guinness World Records, Roger Squires from the UK is the most active crossword maker. By May 14, 2007, he had published 66,666 crosswords!

- The longest word ever used in a published crossword is the 58-letter Welsh town name Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch. It was clued as an anagram.

- In Japanese language crosswords, one syllable (usually katakana) goes into each white square instead of one letter. This makes the grids look smaller.

- Manny Nosowsky holds the record for publishing the most crosswords in The New York Times, with 241 puzzles.

- Swedish crosswords often use pictures or drawings as clues. The clues are inside the grid cells, with arrows showing where to fill in the answers.

Related pages

Images for kids

-

A 1925 Punch cartoon about "The Cross-Word Mania". A man phones his doctor in the middle of the night, asking for "the name of a bodily disorder of seven letters, of which the second letter must be 'N'".

-

A Bengali crossword grid

See also

In Spanish: Crucigrama para niños

In Spanish: Crucigrama para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |