Frederick II of Denmark facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Frederick II |

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Hans Knieper, 1581.

|

|

| King of Denmark and Norway (more...) | |

| Reign | 1 January 1559 – 4 April 1588 |

| Coronation | 20 August 1559 Copenhagen Cathedral |

| Predecessor | Christian III |

| Successor | Christian IV |

| Born | 1 July 1534 Haderslevhus Castle, Haderslev, Denmark |

| Died | 4 April 1588 (aged 53) Antvorskov Castle, Zealand, Denmark |

| Burial | 5 August 1588 Roskilde Cathedral, Zealand, Denmark |

| Spouse | |

| Issue Detail |

Elizabeth, Duchess of Brunswick-Lüneburg Anne, Queen of England and Scotland Christian IV, King of Denmark and Norway Ulrik, Prince-Bishop of Schwerin Augusta, Duchess of Holstein-Gottorp Hedwig, Electress of Saxony John, Prince of Schleswig-Holstein |

| House | Oldenburg |

| Father | Christian III of Denmark |

| Mother | Dorothea of Saxe-Lauenburg |

| Religion | Protestantism (Lutheranism) |

| Signature |  |

Frederick II (born 1 July 1534 – died 4 April 1588) was the King of Denmark and Norway and Duke of Schleswig and Holstein from 1559 until his death.

Frederick was a member of the House of Oldenburg, a royal family. He became king at 24 years old. He took over a strong kingdom that his father, Christian III, had built after a civil war called the Count's Feud. After this war, Denmark's economy got better, and the king's power grew stronger.

In his younger years, Frederick was known for being brave and proud. He started his reign by winning a quick war to take back Dithmarschen. However, after a very costly war called the Northern Seven Years' War, he became more careful in how he dealt with other countries. The rest of his time as king was peaceful. Frederick enjoyed hunting and spending time with his advisors. He also focused on building beautiful castles and supporting science. Many building projects began during his reign, including additions to Kronborg Castle and Frederiksborg Castle.

For a long time, people didn't think much of Frederick II because his son, Christian IV, was a very famous king. Frederick was sometimes wrongly described as someone who didn't like to read, drank too much, and was rough. But this idea is not fair or true. Recent studies show that Frederick was actually very smart. He liked to be around learned people and was quick-witted and clear in his letters and laws. Frederick was also a loyal and friendly person who made strong connections with other rulers and his helpers.

In 1572, Frederick married his cousin, Sophie of Mecklenburg. Their marriage was considered one of the happiest royal marriages in Renaissance Europe. They had seven children in their first ten years together and were described as being very close and getting along well.

Frederick wanted to be the most powerful king in the North. For several years, he fought difficult wars against his rival, Erik XIV of Sweden. After these wars, the competition changed. It became about who could show the longest family history and build the most impressive castles. In the 1570s, he built Kronborg, a large Renaissance castle that became famous. Its dance hall was the biggest in Northern Europe at the time. He loved to host guests and throw big parties that were well-known across Europe. During this time, the Danish-Norwegian navy also became one of Europe's largest and most modern. To make his kingdoms stronger, he greatly supported science and culture.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Frederick was born on 1 July 1534 at Haderslevhus Castle. His father was Duke Christian of Schleswig and Holstein, who later became King Christian III of Denmark and Norway. His mother was Dorothea of Saxe-Lauenburg. Frederick's mother was also the sister of Catherine, the first wife of the Swedish king Gustav Vasa. This made Frederick and Eric XIV, his future rival, cousins.

When Frederick was born, a civil war in Denmark, called the Count's Feud, was ending. Just three days after his birth, his father became King of Denmark. The previous king had died, and Denmark had been without a clear ruler for over a year. In Denmark, the king was not automatically chosen by birth (hereditary). Instead, the Council of the Realm, a group of noblemen, elected the king (elective).

Frederick I and his son Christian were strong Protestants who followed Lutheranism. However, many members of the Council of the Realm were Catholic bishops or powerful noblemen who supported the old Catholic Church. After a period of no king and some uprisings, Christian III finally won. He was then declared King of a new Protestant Denmark.

Becoming the Next King

After King Christian III's victory, the king's power in Denmark grew strong again. He made new rules. In a document called a haandfæstning, which all Danish kings had to sign, he reduced the power of the noblemen. He also made a rule that the king's first son would always be the next king (heir apparent) and would take over automatically.

On 30 October 1536, Christian gathered important leaders in Copenhagen. They officially declared Frederick the next king, giving him the title "Prince of Denmark". In 1542, the Prince traveled around Denmark and was welcomed by the people. In 1548, Christian III and Frederick sailed to Oslo, Norway. There, Frederick was also declared the next in line for the Throne of Norway.

Growing Up in the Royal Family

While Christian III took control of Denmark and Norway, his children grew up close to their family. Besides Frederick, his siblings included Anna, Magnus, John (called John the Younger), and Dorothea.

Usually, royal children were sent to live with their grandparents for their upbringing. But Queen Dorothea did not want to send her young children away. Also, her own mother was thought to have Catholic beliefs. In those religious times, a Lutheran Danish king could not let his child be influenced by Catholic ideas. The royal couple also worried about leaving their children out of sight during the difficult political times when Frederick was young.

Frederick's Education

Frederick's education was very thorough, but it focused mainly on Lutheran religious teachings. He learned a lot about theology. A plan was made for him to learn about managing a kingdom, diplomacy, and war. However, this plan was not fully carried out because the relationship between the Danish Chancellor and Christian III became difficult.

Life at the court of Christian III and Dorothea was very religious, following strong Lutheran Christian beliefs. All their children grew up with these values. In 1541, when Frederick was 7, he started school. Hans Svaning, a respected Danish scholar and professor, became his teacher.

Dealing with Dyslexia

Christian III and Dorothea likely had high hopes for Frederick's schooling. Their son seemed smart and had a good memory. So, they must have been very disappointed and surprised when his lessons began. Frederick learned to write neatly, but when it came to reading and spelling, he struggled greatly.

His teacher, Hans Svaning, thought Frederick's poor spelling was due to laziness, since the prince seemed intelligent otherwise. Frederick was likely punished many times, not just by his teacher, but also by his strict mother, who would step in if Svaning's teaching wasn't enough.

Because Frederick had severe dyslexia, people at the time thought he couldn't read or write well. Both his father and mother were worried about him. They kept him under the close watch of knowledgeable men to stop him from speaking publicly. His father also did not give Frederick any important government jobs.

Time at Malmö Castle

It wasn't until Frederick was 20, in 1554, that he was allowed to have his own court at Malmö Castle in Scania. But he was still supervised by an older nobleman, Ejler Hardenberg, who was his court master. At the same time, his political training began, led by two skilled noblemen. The years in Scania must have felt like freedom for Frederick. He finally escaped the strict royal court and its religious daily life. Just outside Malmö Castle was the busy town of Malmö, which offered a young man many new experiences.

While he spent many of his younger years in Scania, he became known as the "Prince of Scania". It is not known if this was an official title.

Travels with his Brother-in-Law

Frederick's only political training came from his close friendship with his brother-in-law, Augustus, Elector of Saxony. Some writers have said that Augustus was the only strong emotional support Frederick had when he was young.

Augustus, who was married to Frederick's older sister Anne, took Frederick under his wing. They traveled through the Holy Roman Empire in 1557–58. There, Frederick met the new emperor, Ferdinand I, his son Maximilian, William of Orange, and many other important German Protestant princes. This experience gave Frederick a lasting understanding of German politics and a liking for military matters.

This worried Frederick's aging father, Christian III. He feared that Frederick would develop ambitions that were too big for his kingdoms. He worried that the trip would pull Denmark-Norway into complicated German politics.

Reign as King

Becoming King

Frederick's father, Christian III, died on 1 January 1559. Frederick was not there when his father passed away. This did not make the new king, Frederick II of Denmark-Norway, popular with the advisors who had respected Christian.

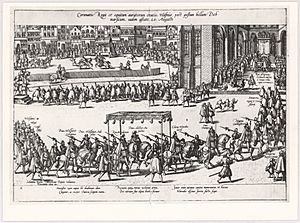

On 12 August 1559, Frederick signed his haandfæstning. This document limited the king's power, similar to England's Magna Carta. On 20 August 1559, Frederick II was crowned at the Church of Our Lady in Copenhagen. The ceremony included Danish and Norwegian church leaders, showing the connection between Denmark and Norway. Week-long celebrations followed the coronation.

Winning Ditmarschen

Within weeks of his father's death, Frederick joined his uncles in Holstein, John and Adolf, in a military campaign to conquer Dithmarschen. Frederick's great-uncle, King John, had failed to take control of this area in 1500. But Frederick's campaign in 1559 was a quick and easy victory for Denmark. The short and cheap war did not comfort the members of the Council of the Realm. They had warned Frederick that a conflict with Sweden was likely, but the king had not listened. He had not even asked the Council about the Ditmarschen campaign.

Working with the Council

The difficult relationship between the king and the Council improved quickly. This was not because Frederick gave in to their demands. Instead, both sides learned to work together because it was important for their interests and for the kingdom. From early on, the Council gave Frederick a lot of power. They did not want to return to the chaotic times before the civil war.

Frederick soon learned how to work with the Council in a monarchy where power was shared. He learned to please the Council without giving up his own royal interests. This meant being generous to the noblemen in the Council with gifts and favors, which he did in a grand way. He gave out lands and properties on very good terms.

The much better relationship between the king and the Council after the Ditmarschen campaign was clearly seen during the biggest national crisis of his reign: the Northern Seven Years' War (1563–70) against Sweden.

The Northern Seven Years' War

King Frederick's competition with Sweden for power in the Baltic Sea led to war in 1563. This was the start of the Northern Seven Years' War, the most important conflict of his rule.

The main advisors, especially Johan Friis, had worried about a Swedish attack for years. When Frederick II's cousin, the ambitious Eric XIV, became king of Sweden, a fight seemed unavoidable. Still, few advisors wanted war. They preferred to wait until they were forced into it, but Frederick wanted to attack first. Despite their first objections, the Council of the Realm supported the king. Frederick II wisely included the Council in leading the war. He kept overall control but gave much responsibility to his advisors.

Only one major problem came up during the war. In late 1569, after six years of fighting, the Council decided not to give the king more money through taxes. The war had cost a lot of lives and money, and Denmark had not gained much since 1565. The Council had already asked Frederick to make peace. He tried a little in 1568, but neither Frederick nor the Swedish king wanted to admit defeat.

The war became very expensive. Areas of Scania were damaged by the Swedes, and Norway was almost lost. During this war, King Frederick II personally led his army on the battlefield. He had some small successes, but overall, there wasn't much progress.

By stopping financial support, the Council hoped to force the king to end the war. Frederick felt betrayed. After thinking about it, he felt the only honorable thing to do was to give up his throne (abdication). With his letter of resignation in the hands of his advisors, he left the capital to go hunting. The king was still unmarried and had no heir. Because of this, the Council of the Realm worried about another period without a leader and even another civil war. This worked in the king's favor. The Council begged him to return to the throne and allowed him to call a meeting to approve more taxes.

The conflict hurt his relationship with his noble advisors. However, the war finally ended with a peace agreement in 1570, which allowed Denmark-Norway to save face but also showed the limits of their military power.

Frederick II learned a lot about being king during the war with Sweden. He learned to include the Council of the Realm in most decisions. But he also learned that he could influence the Council, even get them to agree with him, without making them feel bad or weakening their power. He would later become very good at this skill and use it often.

Later Years of His Reign

During the next eighteen years of his reign, Frederick used the lessons he learned from the war with Sweden. In peacetime, he often moved his court from one royal home to another across the Danish countryside. He spent a lot of his time hunting. This gave him chances to meet members of the Council individually and informally in their own regions. He met the Council of the Realm once a year, but most of his work with them was done one-on-one. This helped him build strong personal connections with each Council member. It also made it harder for the Council to oppose him as a group. Frederick's friendly personality also helped.

Informal Court Life

The king hunted, feasted, and drank with his councillors and advisers, and even with visiting foreign guests. He treated them as equals and friends, not as political rivals or people beneath him. A writer from the 1700s, Ludvig Holberg, said that when dining at Frederick II's court, the king would often announce that ‘the king is not at home’. This meant that all court formalities were paused, and guests could talk and joke freely. While Frederick II's Danish court might have seemed simple to outsiders, its openness and fun atmosphere helped Frederick achieve his political goals. In 1585, he visited Norway for the first and only time as king, but only went to Bohuslen.

Improving Finances

The Northern Seven Years' War cost a lot, about 1.1 million rigsdaler. This money was mostly recovered by raising taxes on Danish and Norwegian farms. After the war, the country's money situation was bad. King Frederick II called Peder Oxe back to help fix the economy. Oxe was a skilled advisor who took over managing Denmark's government and money. This greatly improved the national treasury. Experienced advisors helped manage the country. As a result, government finances were put in order, and Denmark-Norway's economy got better. A key way they improved things was by increasing the Sound Dues, a tax on ships passing through the strait between Denmark and Sweden. Oxe, as the treasurer, greatly reduced the national debt and bought back some royal lands.

Building Projects

After the Northern Seven Years' War, Denmark entered a time of wealth and growth. The king had more money and depended less on the Council for funds. This meant he could spend more freely than his father, Christian III. A lot of money was spent on making the Danish navy bigger and better. This was not just for safety, but also to help Frederick clear the Baltic Sea of pirates. The increased money also allowed Frederick to build Denmark's first national road network, called the kongevej ('King's Road'). This connected the larger towns and the royal homes.

The most noticeable spending was on royal castles and the court itself. Frederick spent a lot on rebuilding several royal homes and other cities:

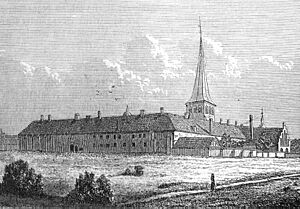

- Antvorskov (near Slagelse, Sjælland) was one of Frederick's favorite hunting castles. He later died there.

- In 1567, King Frederick II founded Fredrikstad in Norway. Frederik II Upper Secondary School in Fredrikstad, a large school in Norway, is named after him.

- He also rebuilt Kronborg in Elsinore. He changed it from a medieval fort into a grand Renaissance castle between 1574 and 1585.

- In 1560, Frederick turned the farm Hillerødsholm in North Sealand into a large Renaissance castle, Frederiksborg.

- In 1561, Frederick II improved and strengthened Skanderborg Castle using materials from Øm Abbey.

Even though Frederick acted informally at his court, he was very aware of his high status. Like most kings of his time, he wanted to improve Denmark's reputation among other European nations. He did this by supporting artists and musicians, and by holding grand ceremonies for royal weddings and other public events.

Kronborg and "The King's Sound"

Frederick II claimed control over 'the king's sound', which was his name for The Sound and all the waters between his lands in Norway and Iceland. In 1583, he made an agreement where England paid a yearly fee to sail there, and France later did the same.

He also tried to make sure that the trade and fishing around Iceland were done by his own people, instead of Englishmen and Germans. He encouraged adventurers like Magnus Heinason. He gave Heinason a special right to trade with the Faeroes, a share in ships caught illegally sailing to the White Sea, and support for a brave but unsuccessful attempt to reach east Greenland.

Supporting the Church and Learning

The king had to keep order within the church, so he often got involved in church matters. There was no longer an archbishop in charge, so the king was the final decision-maker when bishops couldn't agree. His father, Christian III, said that kings were like the ‘father to the superintendents’ (church leaders).

As the protector of the church and its clergy (priests), Frederick often stepped in when there were arguments between priests and ordinary people, even for small issues.

Frederick II often defended new parish priests whose church members tried to force them to marry their predecessors’ widows. He also sometimes protected preachers from powerful noblemen. On the other hand, the king would personally make sure that unruly, incompetent, or disreputable priests lost their churches. Or he would pardon those who had been punished for small mistakes. Protecting and disciplining the clergy was part of the king's duty to the state church.

Frederick II was more active than his father in extending his royal power into areas that were supposed to be separate from government control. Frederick asked for advice from professors at the University of Copenhagen—called the ‘most learned ones’. But he was not afraid to make changes in even the smallest church services. He decided which books every parish priest should have, set standard times for church services in towns, and set minimum standards for all preachers.

Even though Frederick got involved a lot in church matters, historian Paul Douglas Lockhart said that Frederick "was not interested in telling people what to believe". Lockhart stated that Frederick "only wanted to prevent useless religious arguments, arguments that could weaken the kingdom and leave it open to Catholic attacks".

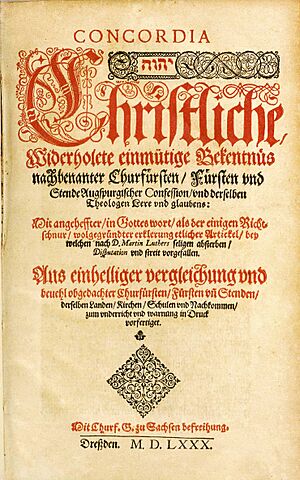

The Book of Concord

Frederick's strong dislike for religious arguments can be seen in his reaction to a Lutheran statement of faith called the Formula and Book of Concord. This ‘Concord’ was written by leading church scholars from Saxony and supported by Frederick II's brother-in-law, Augustus, Elector of Saxony. It was an attempt to bring unity among the German Lutheran princes. However, the Concord failed to create unity.

Augustus had recently removed Calvinists and other groups from his court. So, very strict Lutherans wrote the document. The Concord was extremely traditional. Frederick II had already argued with his old friend Augustus about religious issues. In 1575, Augustus complained about the Calvinist ideas in a book by Niels Hemmingsen. Although Frederick tried to defend Hemmingsen, who was his favorite scholar, he also wanted to keep Augustus's friendship. So, he honorably removed Hemmingsen from his job at the University of Copenhagen in 1579. Frederick was not as open to Augustus promoting the Concord.

Like many people at the time, Frederick believed that the Book of Concord caused arguments, not harmony. He ignored Augustus's warnings that Calvinist ideas had spread among Denmark's clergy. In July 1580, he banned the Concord from his lands. Owning the book, or even talking about its contents, would be severely punished. The king burned his own copies, which his sister Anne had sent him. He argued that the Concord contained "teachings which are foreign and alien to us and to our churches, [and which] could easily disrupt the unity which ... these kingdoms have hitherto maintained".

Frederick's Interests

Even though he was sometimes called a drunkard who didn't like to read and left state matters to his advisors to go hunting, this is wrong. Frederick was very intelligent. He loved being around learned men, who were part of his close group of thinkers. They had many interests.

University of Copenhagen

Frederick was a great supporter of the University of Copenhagen. He made changes to education there in the 1570s and 1580s. Frederick greatly increased the university's money, hired more teachers, and paid them much higher salaries. While he demanded higher standards from priests, Frederick and his advisors also gave more help to students who were poor. One hundred students, chosen by the university, received free room and board from the king for five years. Four especially promising students would get a special scholarship that paid for all their costs to study abroad, as long as they returned to Copenhagen to finish their doctorate.

Medicine

Frederick II and his group of wise men were interested in more than just theology. Frederick was very interested in Paracelsian medicine. In 1571, he appointed Johannes Pratensis to the medical department of the University of Copenhagen. In the same year, Petrus Severinus became his personal doctor. Severinus had a lot of influence among Paracelsian doctors after his book Idea medicinæ philosophicæ was published in 1571.

Astronomy and Tycho Brahe

Frederick II was fascinated by alchemy (an early form of chemistry) and astrology (the study of how stars affect people). This interest helped the astronomer Tycho Brahe become famous around the world as a pioneer in Europe's Scientific Revolution. Tyge Brahe came from a very high-ranking Danish noble family. His father was a landowner and a member of the Council of the Realm.

After studying a lot abroad, Tycho Brahe returned to Denmark. Instead of working for the state like other noblemen, he went to a monastery where he and his uncle experimented with making paper and glass. They also had a private observatory. Brahe wrote about a supernova (a new bright star) that appeared in 1572. This book brought his work to the attention of Frederick and his court. The king insisted that Brahe give lectures at the University of Copenhagen in 1574. Two years later, he was given the island of Ven as his own land. He wasn't great at managing the land, but his observatory there, called Uraniborg, attracted students from all over Europe. From 1576 until he was asked to leave by Christian IV in 1597, Brahe ran the first scientific research center in Europe that was paid for by the government.

Supporting Science

In his later life, Frederick was careful with state money. But he gave a lot of royal support when it was for learning and knowledge. For example, even after he removed Hemmingsen from the University of Copenhagen in 1579, he made sure the theologian still had a good salary and could continue to study. Tycho Brahe received not only Ven as a ‘free fief’ (land he could use without much payment), but also other lands and farms to pay for his work at Uraniborg.

Frederick himself chose the island of Ven as a place where Brahe could do his experiments without being disturbed. Perhaps the king wanted to make Denmark look good among the great nations of Europe. But he also showed a strong appreciation for smart people.

As Paul Douglas Lockhart later said: "Frederick II may have had trouble reading and writing (...) but he was enlightened as few kings of his time were. It is hard to see how Danish historians for so long thought he was little better than a drunken fool".

Hunting and Feasting

Frederick's interests were not only in theology and science. He was also well known for his love of hunting, drinking, and feasting. In his youth and early reign, this was a way for Frederick to escape the strict rules of the Danish court. However, later in his reign, he started using hunting and feasting as a political tool. During peacetime, Frederick would often move his court from one royal home to another across the Danish countryside, spending a lot of his time hunting. This gave him chances to meet members of the Council individually and informally in their own regions. Most of his work with the Council of the Realm was done one-on-one. This helped him build strong personal connections with each Council member. It also made it harder for the Council to oppose him as a group. Frederick's friendly personality certainly helped.

Family and Marriage

Anne Hardenberg

As a young man, Frederick II wanted to marry a noblewoman named Anne Hardenberg. She was a lady-in-waiting to his mother, the Dowager Queen Dorothea of Denmark. However, she was not born into a royal family, so marriage was not possible. There is no sign that either of them wanted a marriage where Anne would not have royal status. Anne Hardenberg married six months after Frederick, and there is no known contact between them after that.

Marriage to Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow

On 20 July 1572, Frederick married Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow. She was a descendant of King John of Denmark and also his own first cousin.

Sophie was the daughter of Ulrich III, Duke of Mecklenburg-Güstrow and Elizabeth of Denmark. Their marriage was happy and peaceful. Frederick often wrote about Sophie in his diary as "mynt Soffye," meaning "my Sophie." She traveled with him across the country as the court moved often. Queen Sophie was a loving mother who personally cared for her children when they were sick. When Frederick had malaria in 1575, she nursed him herself and wrote many worried letters to her father about his recovery.

After Frederick's death, Sophie received a special payment and lands, including Nykøbing Castle and the islands of Lolland and Falster. Dowager Queen Sophie managed her lands so well that her son could borrow money from her many times for his wars.

Children

Frederick and Sophie had seven children:

| Name | Portrait | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elizabeth of Denmark |  |

25 August 1573 | 19 June 1625 | She married Henry Julius, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg in 1590. They had 10 children. |

| Anne of Denmark |  |

12 December 1574 | 2 March 1619 | She married King James VI of Scotland (later King James I of England) in 1589. They had 7 children. |

| Christian IV, King of Denmark and Norway |  |

12 April 1577 | 28 February 1648 | He married Anne Catherine of Brandenburg in 1597. They had 7 children.

He later married Kirsten Munk. They had 12 children. |

| Ulrik of Denmark |  |

30 December 1578 | 27 March 1624 | He became the last Bishop of Schleswig (1602–1624).

He also became Ulrich II as Administrator of the Prince-Bishopric of Schwerin (1603–1624). He married Lady Catherine Hahn-Hinrichshagen. |

| Augusta of Denmark |  |

8 April 1580 | 5 February 1639 | She married John Adolf, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp in 1596. They had 8 children. |

| Hedwig of Denmark |  |

5 August 1581 | 26 November 1641 | She married Christian II, Elector of Saxony in 1602. They had no children. |

| John of Denmark, Prince of Schleswig-Holstein |  |

9 July 1583 | 28 October 1602 | He was supposed to marry Tsarevna Ksenia, daughter of Boris Godunov, Tsar of Russia, but he died before the wedding. |

Death and Burial

King Frederick II died on 4 April 1588, at the age of 53, at Antvorskov Castle.

He was buried on 5 August 1588 in Christian I's chapel at Roskilde Cathedral. Later, his son King Christian IV of Denmark built a large monument there to honor his father.

Legacy and Reputation

Many modern historians, like Poul Grinder-Hansen and Paul Douglas Lockhart, believe that Frederick II's reign, especially his later years, was a great success. For a long time, Danish historians wrongly described Frederick as someone who couldn't read, was foolish, and not very smart. They thought he left state matters to his advisors to go hunting in the countryside.

However, this idea is incorrect. Frederick was very intelligent. He loved being around learned men, who were part of his close group of thinkers. They had many interests, including medicine, alchemy, astrology, and theology. As Paul Douglas Lockhart later said: "Frederick II may have had trouble reading and writing (...) but he was enlightened as few kings of his time were. It is hard to see how Danish historians for so long thought he was little better than a drunken fool".

Changing Views of Frederick

The negative image of Frederick II was first created by the historian Troels Frederik Lund in his 1906 book about Peder Oxe. Lund believed that Oxe saved Denmark from the foolish young king and his war-crazy German officers.

Frederick was often described as stubborn and quick to anger. In his early twenties, he showed a strong love for hunting. These are the traits that Danish historians often focused on. This led to the common idea of Frederick as a man and king who couldn't read, drank too much, and was rough. People thought he almost gave up his kingly duties to go hunting.

However, this portrayal is unfair and wrong. Thanks to the research of Frede P. Jensen, this view has been changed. Frede P. Jensen (1940–2008), after careful study of old records, was one of the first historians in Denmark to completely change how King Frederick II was seen.

Frederick was indeed not a great scholar, mostly because he had severe dyslexia. Throughout his life, he struggled with reading and writing, and it made him very embarrassed. But, as those close to him would say, he was very intelligent. He loved the company of learned men. In the letters and laws he told his secretaries to write, he showed himself to be quick-witted and clear. Frederick was also open and loyal. He was good at forming close personal bonds with other princes and with those who served him. These qualities made him an excellent politician. In fact, Frederick took his father's main legacy – the close cooperation between king and noblemen – to its fullest extent. At the same time, he brought Denmark to its highest point of power and influence in Europe.

The rebirth of the University of Copenhagen and the better organization of the government, along with the importance of learned men in the king's inner circle, gave Frederick II's court a unique and scholarly feel that his father's court lacked. This, in turn, led to more intellectual activity throughout the kingdom. Literature, mostly about theology, grew popular in the second half of the century.

Titles and Symbols

Titles and Styles

- 30 October 1536 – 1 January 1559: Frederick, Prince of Denmark

- 1554 – 1 January 1559 (While in Scania ): Frederick, Prince of Scania

- 1 January 1559 – 4 April 1588: By the Grace of God, King of Denmark and Norway, the Wends and the Goths, Duke of Schleswig, Holstein, Stormarn and Dithmarschen, Count of Oldenburg and Delmenhorst.

Coat of Arms

|

|

|---|---|

| Coat of arms of Frederick as King of Denmark and Norway. | Coat of arms of Frederick as Knight of the Order of the Garter. |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Federico II de Dinamarca para niños

In Spanish: Federico II de Dinamarca para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |