Hussites facts for kids

The Hussites were a Christian group from the Czech Republic (then called Bohemia). They followed the ideas of a reformer named Jan Hus. This movement was a big part of the Bohemian Reformation, which happened before the larger Protestant Reformation.

After Jan Hus was executed, a series of wars and conflicts began. These were known as the Hussite Wars (1420–1434). Different Hussite groups had their own ideas, but eventually, the moderate Hussites, called Utraquists, became the main group. They even gained legal equality with Catholics in Bohemia in 1485.

For about 200 years, Bohemia and Moravia (which are now part of the Czech Republic) had many Hussites. But after the Battle of White Mountain in 1620, the Holy Roman Emperor brought back Roman Catholicism. Today, the Hussite tradition continues in churches like the Moravian Church and the Czechoslovak Hussite Church.

Contents

The Story of the Hussites

The Hussite movement started in the Kingdom of Bohemia. It quickly spread to other areas like Moravia and Silesia. It also reached parts of what is now Slovakia. However, in some places, Hussite soldiers were known for taking things, which gave them a bad name.

There were also small Hussite groups in Poland and Transylvania. But these groups often moved to Bohemia because of religious intolerance. The Hussite movement mostly stayed within the Bohemian lands.

The Hussites had different groups. The largest was the Utraquists (moderates). There was also a strong group called the Taborites (radicals). Other smaller groups included the Adamites, Orebites, and Orphans.

Important Hussite thinkers included Petr Chelčický and Jerome of Prague. Many Czech national heroes were Hussites, like Jan Žižka. He bravely led the fight against five crusades sent by the Pope to attack Hussite Bohemia. The Hussites were very important forerunners of the Protestant Reformation. This religious movement also helped strengthen the national identity of the Czech people.

The Death of Jan Hus

Jan Hus was invited to the Council of Constance with a promise of safety. But he was arrested, tried for heresy, and burned at the stake on July 6, 1415.

His arrest in 1414 made many people in the Czech lands very angry. They asked King Sigismund to release him. When news of Hus's death arrived, people in Bohemia were furious. They protested against the clergy and monks. Even the Archbishop barely escaped the public's anger.

People felt Hus's death was a terrible insult to their country. King Wenceslaus IV was also angry with Sigismund. His wife openly supported Hus's friends. Hussite leaders even held positions in the government.

Some lords formed a group to protect the free preaching of the Gospel. They promised to follow bishops only if their orders matched the Bible. The university would help settle any disagreements. Many Hussite nobles joined this group.

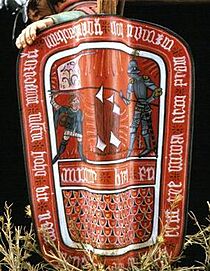

By 1417, some nobles started removing Catholic priests from their churches. They replaced them with priests who would give communion in both wine and bread. The chalice (cup of wine) became a key symbol for the Hussite movement. King Wenceslaus did not join this group. Instead, he supported the Roman Catholic League of lords. This group promised to support the king, the Catholic Church, and the council. It looked like a civil war was about to begin.

Before becoming Pope, Martin V was a cardinal who strongly opposed Hus. He continued to fight against Hus's teachings after the Council of Constance. He wanted to completely get rid of Hus's ideas. In 1418, King Sigismund convinced his brother, King Wenceslaus, to agree with the council. Sigismund warned that a religious war was unavoidable if the "heretics" in Bohemia were still protected.

Hussite leaders and army commanders had to leave the country. Catholic priests were brought back. These actions caused a lot of unrest. King Wenceslaus died in 1419 from a stroke, possibly due to the stress. His heir was Sigismund.

The Hussite Wars (1419–1434)

When King Wenceslaus died in 1419, the people of Prague were in an uproar. A revolution swept through the country. Churches and monasteries were destroyed, and Hussite nobles took church property. It was unclear if Bohemia was a hereditary kingdom (passed down) or an elective one (chosen by nobles). Sigismund could only claim the throne by force.

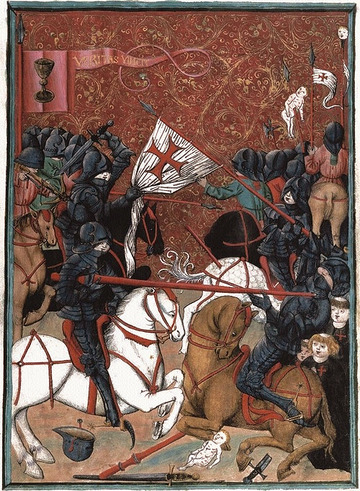

Pope Martin V called on Catholics to fight the Hussites, starting a crusade. This led to twelve years of fighting. At first, the Hussites fought to defend themselves. But after 1427, they began to attack. Besides their religious goals, they also fought for the rights of the Czech people.

The moderate and radical Hussite groups united. They not only pushed back the crusader armies but also raided neighboring countries. On March 23, 1430, Joan of Arc threatened to lead an army against the Hussites if they did not return to the Catholic faith. However, she was captured two months later, so she could not carry out her threat.

Peace Talks and Agreements

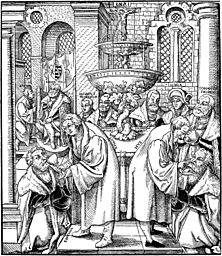

Eventually, the enemies of the Hussites had to consider making peace. The Hussites were invited to attend the ecumenical Council of Basel on October 15, 1431. Discussions began on January 10, 1432. They mainly focused on the Four Articles of Prague. No agreement was reached at first.

After many talks between the Basel Council and Bohemia, a Bohemian assembly in Prague accepted the "Compactata" of Prague on November 30, 1433. This agreement allowed communion in both kinds (bread and wine) for anyone who wanted it. However, it also stated that Christ was fully present in both. Other Hussite reforms were not to be emphasized as much. Free preaching was allowed, but church leaders had to approve and place priests. The rule against clergy having worldly power was almost reversed.

The radical Taborites refused to agree to these terms. So, the moderate Calixtines joined with the Roman Catholics. They defeated the Taborites at the Battle of Lipany on May 30, 1434. After this, the Taborites lost their power. The Hussite movement continued in Poland for five more years until Polish forces defeated the Polish Hussites.

In 1436, the assembly in Jihlava confirmed the "Compactata," making them law. This brought Bohemia back into agreement with Rome and the Western Church. Finally, Sigismund became King of Bohemia. His strict rules caused more unrest, but he died in 1437. In 1444, the Prague assembly rejected some of Wyclif's teachings that the Utraquists disliked. Most Taborites then joined the Utraquists. The rest joined the "Brothers of the Law of Christ" ("Unitas Fratrum"), which is part of the history of the Moravian Church.

Hussites and the Reformation (1434–1618)

In 1462, Pope Pius II canceled the "Compacta." He banned communion in both kinds and recognized King George of Podebrady as king. But this was only if the king promised to fully agree with the Roman Church. The king refused, which led to the Bohemian–Hungarian War (1468–1478).

King Vladislaus II, who came after George, favored the Roman Catholics. He acted against some strong Calixtine clergymen. The problems for the Utraquists grew each year. In 1485, at the Diet of Kutná Hora, Catholics and Utraquists made an agreement that lasted for 31 years. It was not until 1512 that both religions were permanently given equal rights.

When Martin Luther appeared, the Utraquist clergy welcomed him. Luther himself was surprised to find so many similar ideas between Hus's teachings and his own. However, not all Utraquists liked the German Reformation. A split happened among them. Many returned to the Roman Catholic faith, while others had already formed the "Unitas Fratrum" in 1457.

Persecution Under the Habsburgs (1618–1918)

Under Emperor Maximilian II, the Bohemian assembly created the Confessio Bohemica. This was an agreement that Lutherans, Reformed, and Bohemian Brethren all accepted. From this time, Hussitism began to fade.

After the Battle of the White Mountain on November 8, 1620, the Roman Catholic Faith was strongly brought back. This completely changed the religious situation in the Czech lands.

Leaders and members of the Unitas Fratrum had to choose. They could either leave the many different areas of the Holy Roman Empire (like Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, Moravia, and parts of Germany) or practice their faith secretly. As a result, many members went underground or spread across northwestern Europe. The largest remaining groups of the Brethren were in Lissa (Leszno) in Poland and small, hidden groups in Moravia. Some, like Jan Amos Comenius, fled to western Europe, mainly the Low Countries. A group of Hussites settled in Herrnhut, Saxony (now Germany), in 1722. This led to the creation of the Moravian Church.

Modern Times (1918–Present)

In 1918, after World War I, the Czech lands became independent from the Habsburg monarchy (Austria-Hungary). They formed Czechoslovakia. This was partly thanks to leaders like Masaryk and the Czechoslovak legions, who carried on the Hussite tradition.

Today, the Hussite tradition lives on in the Moravian Church, Unity of the Brethren, and the Czechoslovak Hussite Church.

Hussite Groups

The Hussite movement was not one single group. It had different factions with different ideas. These groups sometimes even fought each other during the Hussite Wars. From the beginning, there were two main parties. A smaller group followed the peaceful teachings of Petr Chelčický. His ideas later helped form the Unitas Fratrum.

Hussites can be divided into:

- Moderate Hussites

- Prague Hussites

- Bohemian Hussite nobility

- Hussites of Žatec and Louny

- Other Utraquists/Calixtines

- Radical Hussites

- Taborites

- Orebites

- Adamites

- Orphans

- Other Radical Hussites

Moderate Hussites

The more traditional Hussites were called the moderate party, or Utraquists. They wanted to reform the Church but keep its structure and ceremonies mostly the same.

Their main goals were listed in the Four Articles of Prague. These were written by Jacob of Mies in July 1420. They were published in Latin, Czech, and German. The full text is long, but they are often summarized as:

- Freedom to preach the word of God.

- Allowing everyone to receive communion under both kinds (both bread and wine).

- Clergy should be poor, and church property should be taken by the state.

- People who commit serious sins should be punished, no matter how important they are.

The ideas of the moderate Hussites were popular at the university and among the people of Prague. So, they were also called the Prague Party. They were also known as Calixtines (from Latin calix meaning "chalice") or Utraquists (from Latin utraque meaning "both"). This is because they strongly believed in the second article of Prague, and the chalice became their symbol.

Radical Hussites

The more radical groups, like the Taborites, Orebites, and Orphans, followed the ideas of John Wycliffe more closely. They strongly disliked the monks and wanted the Church to return to how it was during the time of the apostles. This meant getting rid of the current church leaders and taking away church property.

Most importantly, they believed in Wycliffe's ideas about the Lord's Supper. They did not believe in transubstantiation (the idea that the bread and wine literally become the body and blood of Christ). This was a key difference from the moderate Hussites.

The radicals preached "sufficientia legis Christi" (the law of Christ is enough). This meant they believed the Bible was the only rule for human society, not just in the church but also in politics and daily life. Because of this, as early as 1416, they rejected anything they felt was not in the Bible. This included things like honoring saints and images, fasts, extra holidays, oaths, prayers for the dead, private confession, indulgences, and the sacraments of Confirmation and Anointing of the Sick. They also chose their own priests.

The radicals gathered in different places across the country. Their first armed attack was on the small town of Ústí. But since it was not easy to defend, they moved to the ruins of an older town on a nearby hill. They built a new town there and named it Tábor. This name meant "camp" in Czech, but it was also the traditional name of the mountain where Jesus was expected to return. Because of this, they were called Táborité (Taborites). They were the main fighting force of the radical Hussites.

Their goal was to destroy the enemies of God's law and defend his kingdom, which they expected to come soon, by fighting. Their predictions about the end of the world did not come true. To protect their settlement and spread their ideas, they fought bloody wars. At first, they had very strict rules. They punished murder as severely as smaller faults like perjury (lying under oath) and usury (lending money with very high interest). They also tried to apply strict Biblical rules to the social order of their time. The Taborites often had the support of the Orebites (later called Orphans), another Hussite group from eastern Bohemia.

See also

- Arnoldists

- Hussite Bible

- Lollards

- Pavel Kravař

- Restorationism

- Jistebnice hymn book

- Waldensians

- War wagon

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |