Gemistos Plethon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Gemistos Plethon

|

|

|---|---|

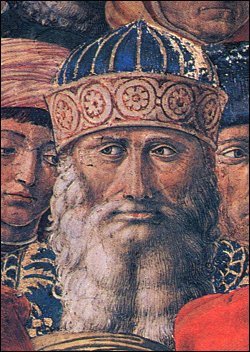

Portrait of Gemistos Plethon, detail of a fresco by acquaintance Benozzo Gozzoli, Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence, Italy.

|

|

| Born | 1355/1360 |

| Died | 1452/1454 |

| Era | Renaissance philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Byzantine philosophy Neoplatonism |

|

Main interests

|

Plato's Republic, Ancient Greek religion, Zoroastrianism |

|

Notable ideas

|

Comparing the similarities and differences between Plato and Aristotle |

|

Influenced

|

|

Georgios Gemistos Plethon (Greek: Γεώργιος Γεμιστός Πλήθων; Latin: Georgius Gemistus Pletho around 1355/1360 – 1452/1454), usually known as Gemistos Plethon, was a brilliant Greek scholar and one of the most famous philosophers of the late Byzantine period. He was a key person in bringing Greek learning back to Western Europe. In his last book, the Nomoi (or Book of Laws), which he only shared with close friends, he explored ancient wisdom. This wisdom was based on ideas from Zoroaster and the Magi, mixed with the worship of classical Greek gods.

In 1438–1439, he helped bring Plato's ideas back to Western Europe. This happened during the Council of Florence, where people tried to unite the Eastern and Western churches. There, Plethon met and influenced Cosimo de' Medici. Cosimo was inspired to start a new Platonic Academy. This academy, led by Marsilio Ficino, later translated all of Plato's works into Latin. They also translated works by Plotinus and other Neoplatonist thinkers.

Plethon also shared his ideas about how a government should work. He once proudly said, "We are Hellenes by race and culture." He suggested a new Byzantine Empire based on an ideal Greek system of government. This system would be centered in Mystras. Because of these ideas, Plethon has been called both "the last Hellene" and "the first modern Greek."

Contents

Plethon's Life and Influence

Early Life and Studies

Georgios Gemistos Plethon was born in Constantinople between 1355 and 1360. He grew up in a well-educated Christian family. He studied in Constantinople and Adrianople before returning to Constantinople. There, he became a philosophy teacher. Adrianople was the Ottoman capital at the time. It was a learning center, similar to Cairo and Baghdad. Plethon admired Plato so much that he later changed his name to Plethon, which has a similar meaning.

Before 1410, Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos sent him to Mystras in southern Greece. Mystras became his home for the rest of his life. In Constantinople, he had been a senator. He continued to serve in public roles, like being a judge. Rulers of Mystras often asked for his advice. Even though the Church suspected him of having different beliefs, the Emperor held him in high regard.

In Mystras, he taught and wrote about philosophy, astronomy, history, and geography. He also summarized many classical writers' works. His students included important figures like Bessarion and George Scholarius. George Scholarius later became a church leader and Plethon's opponent. Plethon became the chief judge for Theodore II. He wrote his most important works during his time in Italy and after he returned home.

The Council of Florence

In 1428, Emperor John VIII asked Plethon for advice. The Emperor wanted to unite the Greek and Latin churches. Plethon suggested that both sides should have equal voting power. Byzantine scholars had been in touch with Western European scholars for a long time. This contact grew when the Byzantine Empire needed help against the Ottomans.

Western Europe knew some ancient Greek philosophy through the Catholic Church and Muslim scholars. But the Byzantines had many documents and ideas that Westerners had never seen. Byzantine knowledge became more available to the West after 1438. That year, Emperor John VIII attended the Council of Ferrara, later called the Council of Florence. The goal was to discuss uniting the Eastern (Orthodox) and Western (Catholic) churches. Even though Plethon was not a church expert, he was chosen to go with John VIII. He was known for his great wisdom and good character. Other delegates included his former students Bessarion and Gennadius Scholarius.

Plethon and the Renaissance

Some scholars in Florence invited Plethon to teach. He set up a temporary school to explain the differences between Plato and Aristotle. At that time, few of Plato's writings were studied in Western Europe. Plethon essentially brought much of Plato's work back to the Western world. This challenged the strong influence that Aristotle had held over Western European thought for centuries.

It is believed that Cosimo de' Medici attended Plethon's lectures. Cosimo was then inspired to create the Accademia Platonica in Florence. Italian students of Plethon continued to teach there after the council ended. However, some historians say that Cosimo and Plethon might not have understood each other well due to language differences. Also, Ficino's "Platonic Academy" was more like an informal study group. Still, Plethon became a very important influence on the Italian Renaissance. Marsilio Ficino, a Florentine scholar and the first leader of the Accademia Platonica, greatly admired Plethon. He called him 'the second Plato'.

While in Florence, Plethon wrote a book called Wherein Aristotle disagrees with Plato. It is often called De Differentiis. He wrote it to correct misunderstandings he had noticed. He said he wrote it "without serious intent" while sick, "to comfort myself and to please those who are dedicated to Plato." Gennadius Scholarius responded with a Defence of Aristotle. This led to Plethon's Reply. Scholars from Byzantium and later Italian humanists continued this debate.

Plethon died in Mystras in 1452 or 1454. In 1466, some of his Italian followers, led by Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, took his remains from Mystras. They buried him in the Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini. They wanted "the great Teacher to be among free men."

Plethon's Writings and Ideas

Ideas for Reforming the Peloponnese

Plethon believed that the people of the Peloponnese were direct descendants of the ancient Greeks. He wanted to bring back the Hellenistic civilization. This was a time when Greek influence was at its peak. In his writings from 1415 and 1418, he urged the rulers Manuel II Palaiologos and Theodore II Palaiologos to make the peninsula a special cultural area. He suggested a new government with a strong central ruler. This ruler would be advised by a small group of educated middle-class men.

He thought the army should only be made of professional Greek soldiers. These soldiers would be supported by taxpayers, called "Helots", who would not have to serve in the military. Land would be owned by the public. One-third of all goods produced would go to the state. People would be encouraged to farm new land. Trade would be controlled, and using coins would be limited. Instead, people would be encouraged to trade goods directly. Local products would be favored over imports. These social and political ideas came mostly from Plato's Republic. Plethon did not talk much about religion in these writings. However, he did not like monks, saying they "render no service to the common good." He suggested three simple religious ideas: belief in a supreme being; that this being cares for people; and that it is not influenced by gifts or flattery. Manuel and Theodore did not put any of these reforms into action.

De Differentiis

In De Differentiis, Plethon compared Plato's and Aristotle's ideas about God. He argued that Plato gave God more powerful roles. Plato's God was the "creator of every kind of intelligible and separate substance, and hence of our entire universe." Aristotle's God, however, was only the force that moved the universe. Plato's God was also the purpose and final reason for existence. Aristotle's God was only the end of movement and change.

Plethon criticized Aristotle for discussing small things like shellfish and embryos. He felt Aristotle failed to give God credit for creating the universe. He also disagreed with Aristotle's idea that the heavens were made of a fifth element. Plethon also disliked Aristotle's view that thinking was the greatest pleasure. Plethon said this idea made Aristotle similar to Epicurus. He also linked this pleasure-seeking to monks, accusing them of being lazy. Later, in response to Gennadius Scholarius' Defence of Aristotle, Plethon argued that Plato's God was more in line with Christian beliefs than Aristotle's. This was likely an attempt to avoid being suspected of having different religious views.

Nomoi (Book of Laws)

After Plethon's death, his book Nómōn syngraphḗ (Νόμων συγγραφή) or Nómoi (Νόμοι, "Book of Laws") was found. Princess Theodora, wife of Demetrios Palaiologos, received the manuscript. Theodora sent it to Scholarius, who was now Gennadius II, the Patriarch of Constantinople. She asked for his advice on what to do with it. He told her to destroy it.

The region of Morea was being invaded by Sultan Mehmet II. Theodora escaped to Constantinople with Demetrios. There, she gave the manuscript back to Gennadius. She did not want to destroy the only copy of such an important scholar's work herself. Gennadius burned it in 1460. However, in a letter to Exarch Joseph (which still exists), he described the book. He included chapter headings and short summaries of its contents.

The book seemed to combine Stoic philosophy and Zoroastrian spiritual ideas. It talked about astrology, spirits, and the journey of the soul. Plethon suggested religious rituals and songs to honor the classical gods, like Zeus. He saw these gods as universal principles and planetary powers. He believed humans, as relatives of the gods, should try to be good. Plethon thought the universe had no beginning or end. He believed it was created perfectly, so nothing could be added to it. He did not believe in a short period of bad times followed by endless happiness. He thought the human soul was reborn, guided by the gods into new bodies to fulfill a divine plan. He believed this same divine plan guided bees, ants, spiders, plant growth, magnets, and how mercury and gold mix.

In his Nómoi, Plethon outlined plans to completely change the Byzantine Empire. He wanted to base it on his understanding of Platonism. The new state religion would be based on a system of ancient gods. This was largely influenced by the humanism popular at the time. It included ideas like rationalism and logic. As a temporary step, he also supported uniting the two churches. This was to get Western Europe's help against the Ottomans. He also suggested more immediate actions. For example, he wanted to rebuild the Hexamilion. This was an ancient defensive wall across the Isthmus of Corinth, which the Ottomans had broken through in 1423.

His ideas about society and government covered how communities should be formed. He supported a kind ruler as the most stable form of government. He believed land should be shared, not owned by individuals. He also had ideas about social structure, families, and how genders and classes should be organized. He thought workers should keep one-third of what they produced. He also believed soldiers should be professionals. He felt that love should be private, not because it was shameful, but because it was sacred.

Summary of Nomoi

Plethon's own summary of the Nómoi also survived. It was found among the papers of his former student Bessarion. This summary, called Summary of the Doctrines of Zoroaster and Plato, confirms the existence of many gods. Zeus is the supreme ruler, holding all existence within himself. His oldest child, without a mother, is Poseidon. Poseidon created the heavens and rules everything below, bringing order to the universe. Zeus's other children include many "supercelestial" gods, the Olympians and Tartareans, all without mothers. Among these, Hera is third in command after Poseidon. She creates and rules indestructible matter. She is also the mother, with Zeus, of the heavenly gods, demi-gods, and spirits. The Olympians rule immortal life in the heavens. The Tartareans rule mortal life below, with their leader Kronos overseeing all mortality. The oldest of the heavenly gods is Helios, master of the heavens and source of all mortal life on Earth. Plethon believed the gods were responsible for much good and no evil. They guide all life towards a divine order. Plethon described the universe as perfect and outside of time. So, the universe remains eternal, without beginning or end. The human soul, like the gods, is immortal and good. It is reborn into different bodies forever, guided by the gods.

Other Works

- On Virtues (Greek: Περὶ ἀρετῶν)

Many of Plethon's other works still exist as old manuscripts in various European libraries. Most of his works can be found in J. P. Migne's Patrologia Graeca collection.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pletón para niños

In Spanish: Pletón para niños

- Greek scholars in the Renaissance

- Christian heresy

- Hellenistic religion

- Polytheistic reconstructionism

- Renaissance humanism

- Renaissance magic