Arabic literature facts for kids

Arabic literature (الأدب العربي) is all the amazing writing, like stories and poems, created by people who write in the Arabic language. The Arabic word for literature, Adab, also means good manners and culture. It's like saying literature helps you become a well-rounded and polite person!

Arabic literature started way back in the 5th century. The Qur'an, which is the holy book of Islam, is seen as the most beautiful piece of writing in Arabic. It had a huge and lasting impact on Arab culture and its literature. Arabic literature really shined during the Islamic Golden Age, and it's still going strong today, with talented writers all over the Arab world and even in other countries.

Contents

History

Early Times: Jahili Period

The Jahili period means "the time of ignorance" before Islam. Back then, in ancient Arabia, there were big markets like Souk Okaz. People from all over the Arabian Peninsula would gather there. At these markets, poets would recite their amazing poems. The dialect spoken by the Quraysh tribe, who controlled the market in Mecca, became very important.

Poetry

Some famous poets from this early time were Abu Layla al-Muhalhel and Al-Shanfara. There were also the poets of the Mu'allaqat, which means "the suspended ones." These were a group of famous poems said to have been displayed in Mecca. Some of these poets include Imru' al-Qais and Antara Ibn Shaddad.

A poet named Al-Khansa was known for her elegy poems, which are sad poems written to remember someone who has died. Another poet, al-Hutay'a, was famous for his panegyric (praise) poems and also for his invective (insulting) poems.

Prose

Most literature from the Jahili period was spoken, not written down. So, we don't have many written stories from that time. The main types of prose were parables (short stories with a moral lesson), speeches, and simple tales.

Quss Bin Sā'ida was a well-known Arab ruler and speaker. Aktham Bin Sayfi was also a famous ruler and a great speech-giver.

The Qur'an

The Qur'an, the main holy book of Islam, had a huge impact on the Arabic language. It marked the start of Islamic literature. Muslims believe it was written in the Arabic dialect of the Quraysh tribe, the same tribe as Muhammad. As Islam spread, the Qur'an helped to unite and standardize the Arabic language.

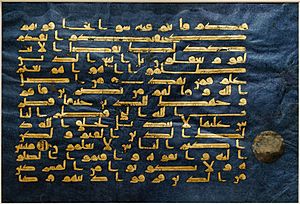

The Qur'an is the first long work written in Arabic. It has a complex structure with 114 chapters (called suwar) and thousands of verses (called ayat). It contains rules, stories, lessons, and direct messages from God. People admire it for its deep meanings and clear language.

The word qur'an comes from an Arabic word meaning "he read" or "he recited." In early times, the text was passed down by speaking it. Later, different parts were collected and written down.

The Qur'an is seen as completely unique, different from regular prose or poetry. Muslims believe it's a divine message and cannot be copied. This idea, called i'jaz (inimitability), meant that no one could truly copy its style.

This idea might have limited Arabic literature a little bit. While Islam allows Muslims to write and read poetry, the Qur'an says that poetry that insults God, praises bad actions, or tries to challenge the Qur'an is forbidden. This might be why there weren't many famous poets until the 8th century. However, Hassan ibn Thabit was an exception; he wrote poems praising Muhammad and was known as the "prophet's poet." Just like the Bible is important in other languages, the Qur'an is central to Arabic literature. It's a source of many ideas, references, and moral lessons.

Besides the Qur'an, the hadith are also very important. These are collections of what Muhammad is believed to have said and done. All these actions and words are called sunnah (way or practice). Some of the most important hadith collections were put together by Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj and Muhammad ibn Isma'il al-Bukhari.

Another important type of writing in Qur'anic study is tafsir, which are commentaries or explanations of the Qur'an. Arabic religious writings also include many speeches and devotional pieces. The sayings of Ali were collected in the 10th century in a book called Nahj al-Balaghah (The Peak of Eloquence).

Rashidi Period

Under the Rashidun (meaning "rightly guided caliphs"), new centers for literature grew in cities like Mecca, Medina, Damascus, Kufa, and Basra. During this time, literature, especially poetry, helped spread Islam. There were also poems to praise brave warriors, inspire soldiers in jihad (holy struggle), and rithā (mourning poems) for those who died in battle. Famous poets from this time include Ka'b ibn Zuhayr and Hasan ibn Thabit.

There was also poetry for fun, often in the form of ghazal (love poems). Famous poets of this style were Jamil ibn Ma'mar and Umar Ibn Abi Rabi'ah.

Umayyad Period

The First Fitna, a big conflict that led to the split between Shia and Sunni Islam over who should be the leader, greatly affected Arabic literature. While literature was very centralized under Muhammad and the Rashidun, it became more divided during the Umayyad Caliphate. Power struggles led to tribalism. Arabic literature went back to how it was in the Jahiliyyah period, with markets where poets recited poems praising or criticizing political groups and tribes. Poets and scholars found support from the Umayyads, but the literature of this time was limited because it served the interests of specific groups and wasn't a free art form.

Important writers of this political poetry include Al-Akhtal al-Taghlibi and Jarir ibn Atiyah.

Abbasid Period

The Abbasid Caliphate period is often called the beginning of the Islamic Golden Age. It was a time when a lot of important literature was created. The House of Wisdom in Baghdad was a famous center for scholars and writers like Al-Jahiz and Omar Khayyam. Many stories in the One Thousand and One Nights feature the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid. Al-Hariri of Basra was another important writer from this time.

Some important poets in Abbasid literature were Bashar ibn Burd and Abu Nuwas.

Andalusi Period

Literature of al-Andalus was created in Al-Andalus, which was Islamic Spain, from 711 until 1492. Ibn Abd Rabbih's Al-ʿIqd al-Farīd (The Unique Necklace) and Ibn Tufail's Hayy ibn Yaqdhan were very important works from this time. Famous writers include Ibn Hazm and Ibn Zaydun. The muwashshah and zajal were popular types of poetry in al-Andalus.

Arabic literature in al-Andalus also grew alongside the golden age of Jewish culture. Most Jewish writers wrote poetry in Hebrew, but some, like Samuel ibn Naghrillah, wrote in Arabic. Maimonides, a famous Jewish scholar, wrote his important book The Guide for the Perplexed in Arabic, using Hebrew letters.

Maghrebi Period

Fatima al-Fihri founded al-Qarawiyiin University in Fes, Morocco, in 859. It's known as the first university in the world! From the 12th century, this university played a big role in developing literature in the region. It welcomed scholars and writers from all over North Africa, Spain, and the Mediterranean. Scholars like Ibn Khaldoun and Maimonides studied and taught there. Sufi literature, which focuses on spiritual and mystical ideas, was also very important.

Mamluk Period

During the Mamluk Sultanate, Ibn Abd al-Zahir and Ibn Kathir were important writers of history.

Ottoman Period

Important poets of Arabic literature during the Ottoman Empire included Al-Busiri, who wrote "Al-Burda", and Ibn al-Wardi. Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi wrote about many different topics, including religion and travel.

Nahda (Renaissance)

In the 19th century, Arabic literature, along with much of Arab culture, experienced a big revival called "al-Nahda" (the renaissance). Writers like Rifa'a at-Tahtawi and Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq wanted to bring back and celebrate Arabic literary traditions.

Translating books from other languages was a huge part of the Nahda. Rifa'a al-Tahtawi was an important translator who started the School of Languages in Cairo in 1835. Later, in the 20th century, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra translated works by famous Western writers like William Shakespeare and Oscar Wilde.

This new wave of Arabic writing mostly happened in cities in Syria, Egypt, and Lebanon at first. Later, in the 20th century, it spread to other countries. This cultural rebirth was noticed outside the Arab world too, with more interest in translating Arabic books into European languages. Even though the Arabic language was revived, many of the overly fancy and complicated styles of older literature were dropped.

Just like in the 8th century, when translating ancient Greek books helped Arabic literature, another translation movement during the Nahda brought new ideas. A popular translated book was The Count of Monte Cristo, which inspired many historical novels about similar Arab subjects. Jurji Zaydan was an important writer in this style.

Poetry

During the Nahda, poets like Francis Marrash and Ahmad Shawqi started to explore new ways of writing classical poetry. Some of these poets knew about Western literature but mostly stuck to classical forms. Others, however, wanted to move away from old traditions and found inspiration in French or English romanticism.

The next generation of poets, called the Romantic poets, were even more influenced by Western poetry. They felt limited by the old rules. The Mahjari poets were Arabs who moved to the Americas and started experimenting with Arabic poetry. This experimentation continued in the Middle East throughout the first half of the 20th century.

Famous poets of the Nahda included Nasif al-Yaziji, Ahmed Shawqi, and Khalil Mutran.

Prose

Rifa'a at-Tahtawi, who lived in Paris from 1826 to 1831, wrote a book called A Paris Profile about his experiences. Butrus al-Bustani started a journal called Al-Jinan in 1870 and began writing the first Arabic encyclopedia. Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq published many important books and edited newspapers.

Adib Ishaq worked in journalism and theater, pushing for more freedom of the press and people's rights. Jamāl ad-Dīn al-Afghānī and Muhammad Abduh started a revolutionary anti-colonial journal. Abd al-Rahman al-Kawakibi and Mustafa Kamil were reformers who influenced public opinion with their writings. Saad Zaghloul was a revolutionary leader known for his powerful speeches.

Ibrahim al-Yaziji founded several newspapers and magazines and translated the Bible into Arabic. Mustafa Lutfi al-Manfaluti wrote many essays encouraging people to awaken and free themselves. Suleyman al-Boustani translated the Iliad into Arabic. Khalil Gibran and Ameen Rihani were two major figures of the Mahjar movement, which involved Arab writers living abroad. Jurji Zaydan founded Al-Hilal magazine in 1892. Other notable figures were Mostafa Saadeq Al-Rafe'ie and May Ziadeh.

Muhammad al-Kattani, who started one of the first Arabic newspapers in Morocco, was a leader of the Nahda in North Africa.

Modern Literature

Starting in the late 19th century, the Arabic novel became a very important way for writers to express themselves. A new group of educated city people, who were influenced by Western ideas, led to new kinds of writing: modern Arabic fiction. This new class of writers used theater and private newspapers to share their ideas, challenge old traditions, and find their place in a changing society.

The modern Arabic novel, especially as a way to criticize society and push for change, moved away from the fancy language of classical literature. It started with translations from French and English. Then came social romance novels by writers like Salīm al-Bustānī. Khalil al-Khuri's Way, Idhan Lastu bi-Ifranjī! (1859-1860) was an early example.

The emotional style of early 20th-century writers like Mustafa Lutfi al-Manfaluti and Kahlil Gibran made the novel seem like an imported Western idea. Writers like Muhammad Taimur focused on short stories instead of novels. Mohammed Hussein Heikal's 1913 novel Zaynab was a mix, with strong emotions but also local characters and settings.

Throughout the 20th century, Arabic writers in poetry, prose, and theater plays showed the changing political and social situations in the Arab world. Early in the 20th century, themes against colonialism were common. Writers continued to explore the region's relationship with the West. Political problems within countries also caused challenges, with writers sometimes facing censorship or persecution.

The period between the two World Wars featured writers like Taha Hussein, author of Al-Ayyām, and Tawfiq al-Hakim. The literature of this time often explored struggles like "Western materialism" versus "Eastern spirituality," or "modern individuals" against a "backward society."

Many modern Arabic writers are still active today. Some, like Sonallah Ibrahim and Abdul Rahman Munif, were even jailed for their critical views. Others who supported governments were given important positions in cultural organizations. Non-fiction writers and academics also wrote political essays to try and change Arab politics. Famous examples include Taha Hussein's The Future of Culture in Egypt, which was important for Egyptian nationalism, and the works of Nawal el-Saadawi, who fought for women's rights.

Poetry

After World War II, some poets tried to write in free verse (shi'r hurr), which doesn't follow strict rhyme or rhythm rules. Iraqi poets Badr Shakir al-Sayyab and Nazik Al-Malaika are seen as the first to use free verse in Arabic poetry. Many of these experiments later moved towards prose poetry. The development of modernist poetry also influenced Arabic poetry. More recently, poets like Adunis have pushed the boundaries even further.

Poetry is still very important in the Arab world. Mahmoud Darwish was considered the national poet of Palestine, and thousands attended his funeral. Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani wrote about less political topics but was a cultural icon, and his poems are used as lyrics for many popular songs.

Novels

In the Nahda period, there were two main trends in novels. One was a classical movement that wanted to bring back old literary traditions, influenced by genres like maqama and One Thousand and One Nights. The other was a modern movement that started by translating Western novels into Arabic.

In the 19th century, writers in Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt created original works by copying old story styles. These included Ahmad Faris Shidyaq's Leg upon Leg (1855) and Francis Marrash's The Forest of Truth (1865). This trend continued with Jurji Zaydan (who wrote many historical novels) and Khalil Gibran. Interestingly, many of these early works have been called the "first Arabic novel," showing that the Arabic novel grew from many different beginnings, not just one. It was influenced by both European novels and the revival of traditional Arabic stories after Napoleon's expedition to Egypt in 1798.

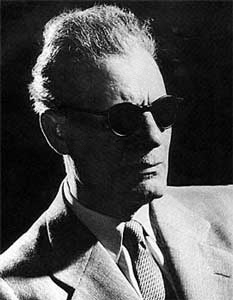

A common theme in modern Arabic novels is family life, which often reflects the wider Arab world. Many novels also deal with the politics and conflicts of the region, with war often being the background for family stories. The works of Naguib Mahfuz show life in Cairo. His Cairo Trilogy, which describes a modern Cairene family over three generations, won him the Nobel prize for literature in 1988. He was the first Arabic writer to win this award.

Plays

The musical plays of Lebanese Maroun Naccache from the mid-1800s are seen as the start of modern Arab theater. Modern Arabic drama began in the 19th century, mostly in Egypt, and was influenced by French plays. It wasn't until the 20th century that it started to have a unique Arab style and appear in other places. The most important Arab playwright was Tawfiq al-Hakim. Other important playwrights include Yusuf al-Ani from Iraq and Saadallah Wannous from Syria.

Classical Arabic Literature

Poetry

A large part of Arabic literature before the 20th century is poetry. Even prose from this time often includes bits of poetry or is written in saj' (rhymed prose). The poems cover many topics, from grand hymns of praise to harsh personal attacks, and from religious ideas to poems about women and wine. An important rule for all Arabic literature was that it had to sound good when spoken. Poetry and much prose were written to be read aloud, so writers took great care to make their words flow beautifully.

Religious Scholarship

Studying the life of Muhammad and finding the true parts of the sunnah (his practices) was an early and important reason for Arabic scholarship. This also led to collecting pre-Islamic poetry, because some of those poets knew the prophet, and their writings helped explain the times. Muhammad also inspired the first Arabic biographies, called Al-Sirah Al-Nabawiyyah. The earliest was by Wahb ibn Munabbih, but Muhammad ibn Ishaq wrote the most famous one. These biographies covered the prophet's life, early Islamic battles, and even older biblical stories.

Some of the first works studying the Arabic language were done for Islam. It's said that the caliph Ali, after seeing errors in a Qur'an copy, asked Abu al-Aswad al-Du'ali to write rules for Arabic grammar. Later, Khalil ibn Ahmad wrote Kitab al-Ayn, the first Arabic dictionary. His student Sibawayh wrote the most respected Arabic grammar book, simply called al-Kitab (The Book).

Other caliphs also helped literature grow. Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan made Arabic the official language of the new empire. Al-Ma'mun set up the Bayt al-Hikma in Baghdad for research and translations. Basrah and Kufah were two other important learning centers.

The institutions created mainly to study Islam also helped in many other subjects. Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik encouraged scholars to translate works into Arabic. One of the first was probably Aristotle's letters to Alexander the Great. From the East, Abdullah Ibn al-Muqaffa translated the animal fables of the Panchatantra. These translations kept knowledge alive, especially from ancient Greece, during Europe's Dark Ages. These works were often reintroduced to Europe through their Arabic versions.

Culinary Literature

More medieval cookbooks written in Arabic have survived than in any other language. Classical Arabic cooking literature includes not just cookbooks, but also scholarly works and descriptions of food in stories like The Thousand and One Nights. Some of these texts are even older than Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq's Kitab al-Tabikh, the earliest known medieval Arabic cookbook.

Early writers knew about the works of ancient Greek doctors like Hippocrates and Galen of Pergamum. Galen's book On the Properties of Foodstuffs was translated into Arabic and used by many medical writers. Abu Bakr al-Razi also wrote an early book on food called Manafi al-Aghdhiya wa Daf Madarriha (Book of the Benefits of Food, and Remedies against Its Harmful Effects).

Non-fiction Literature

Compilations and Manuals

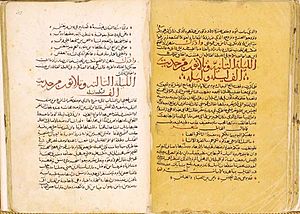

In the late 9th century, Ibn al-Nadim, a bookseller in Baghdad, created a very important work for studying Arabic literature. His Kitab al-Fihrist is a list of all the books available for sale in Baghdad, giving us a great idea of the literature at that time.

One common type of literature during the Abbasid period was the compilation. These were collections of facts, ideas, stories, and poems about a single topic, like gardens, women, or animals. Al-Jahiz was a master of this form. These collections were important for a nadim, a companion to a ruler whose job was to entertain or advise with stories and information.

Another related type of work was the manual, where writers like ibn Qutaybah gave instructions on things like good manners, how to rule, or how to write. Ibn Qutaybah also wrote one of the first histories of the Arabs, combining biblical stories, Arab folk tales, and historical events.

Biography, History, and Geography

Besides the early biographies of Muhammad, the first major biographer to focus on a person's character, not just praise, was al-Baladhuri with his Kitab ansab al-ashraf (Book of the Genealogies of the Noble), a collection of biographies. One of the first important autobiographies was Kitab al-I'tibar, which told about Usamah ibn Munqidh and his experiences fighting in the Crusades. This period also saw the rise of tabaqat (biographical dictionaries).

Ibn Khurdadhbih, a postal service official, wrote one of the first travel books. Travel writing remained popular in Arabic literature, with books by ibn Hawqal, ibn Fadlan, and most famously, the travels of ibn Battutah. These books offer a look at the many cultures of the wider Islamic world and show how powerful Muslim traders had become. These accounts often included details about both geography and history.

Some writers focused only on history, like al-Ya'qubi and al-Tabari. Others focused on smaller parts of history, like ibn al-Azraq with a history of Mecca. The historian considered the greatest of all Arabic historians is ibn Khaldun, whose history Muqaddimah focuses on society and is a founding text in sociology and economics.

Diaries

In the medieval Near East, Arabic diaries started appearing before the 10th century. The medieval diary that most resembles a modern diary was written by Abu Ali ibn al-Banna in the 11th century. His diary was the first to be organized by date, much like diaries today.

Literary Theory and Criticism

Literary criticism in Arabic literature often focused on religious texts. The long traditions of interpreting religious texts greatly influenced how secular texts were studied. This was especially true for Islamic literature.

Literary criticism was also used for other forms of medieval Arabic poetry and literature from the 9th century, notably by Al-Jahiz and Abdullah ibn al-Mu'tazz.

Fiction Literature

Ibn ʿAbd Rabbih's book Al-ʿIqd al-Farīd is considered a very important work of Arabic fiction.

In the Arab world, there was a big difference between al-fus'ha (high-quality, formal language) and al-ammiyyah (everyday language). Not many writers wrote in the common language, as literature was often seen as something that should be educational and purposeful, not just for fun. However, this didn't stop the hakawati (story-teller) from sharing entertaining parts of educational works or many Arabic fables and folk-tales, which were often not written down. Still, some of the earliest novels, including the first philosophical novels, were written by Arab authors.

Epic Literature

The most famous example of Arabic fiction is One Thousand and One Nights (also known as Arabian Nights). It's the best-known Arabic literary work and still shapes many people's ideas about Arabic culture. Interestingly, stories like Aladdin and Ali Baba, often thought to be from One Thousand and One Nights, were not originally part of it. They were first included in a French translation after the translator heard them from a storyteller. The famous character Sinbad is from the Tales.

One Thousand and One Nights is usually grouped with other works of Arabic epic literature. These are often collections of short stories or episodes linked together into a long tale. Most of the versions we have were written down relatively late, after the 14th century, but many of the original stories are probably much older. Types of stories in these collections include animal fables, proverbs, humorous tales, and moral stories.

Maqama

Maqama is a unique form that mixes prose and poetry, using rhymed prose. It's also a mix of fiction and non-fiction. Through a series of short, fictionalized stories based on real-life situations, different ideas are explored. For example, a maqama about musk might seem to compare perfumes but is actually a political satire comparing different rulers. Maqama also uses badi, which means deliberately adding complexity to show the writer's skill with language. Al-Hamadhani is seen as the creator of maqama. This form was very popular and continued to be written even when Arabic literature declined in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Love Literature

A famous example of romantic Arabic poetry is Layla and Majnun, from the 7th century. It's a sad story of never-ending love. Layla and Majnun is part of the "platonic love" (حب عذري) style, where the couple never marries. This theme is common in Arabic literature. Other famous stories of this type include Qays and Lubna and Antara and Abla.

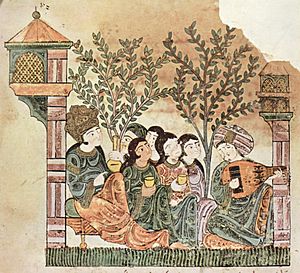

Another medieval Arabic love story was Hadith Bayad wa Riyad (The Story of Bayad and Riyad), from the 13th century. It's about Bayad, a merchant's son from Damascus, and Riyad, a well-educated girl in the court of a minister. The Hadith Bayad wa Riyad manuscript is believed to be the only illustrated manuscript that survived from over eight centuries of Muslim and Arab presence in Spain.

Many stories in One Thousand and One Nights are also love stories or have romantic love as a main theme. This includes the story of Scheherazade herself, and many of the tales she tells, like "Aladdin" and "The Ebony Horse".

Several ideas of courtly love (a medieval European idea of noble love) were developed in Arabic literature. These include "love for love's sake" and "exalting the beloved lady," which can be traced back to Arabic literature of the 9th and 10th centuries. The idea that love can make you a better person was developed in the early 11th century by the Persian philosopher Avicenna in his Arabic book Risala fi'l-Ishq (A Treatise on Love).

Murder Mystery

The earliest known example of a whodunit murder mystery is "The Three Apples", one of the tales in One Thousand and One Nights. In this story, a fisherman finds a locked chest with a dead woman's body inside. The caliph, Harun al-Rashid, orders his minister, Ja'far ibn Yahya, to solve the crime in three days or face execution. The story builds Suspense with many plot twists. This tale can be seen as an early example of detective fiction.

Satire and Comedy

In Arabic poetry, satirical poetry was called hija. Satire was brought into prose literature by al-Jahiz in the 9th century. He wrote about serious topics but added jokes and clever observations to make them more interesting. He knew that when writing about new subjects, he needed to use language that was more familiar from satirical poetry.

In the 10th century, the writer Tha'alibi recorded satirical poems by poets like As-Salami and Abu Dulaf, who would praise each other then mock each other's skills. An example of Arabic political satire was the 10th-century poet Jarir criticizing Farazdaq as someone who broke religious law.

The words "comedy" and "satire" became linked after Aristotle's Poetics was translated into Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. Arabic writers and philosophers like al-Farabi and Avicenna developed these ideas. They saw comedy as simply the "art of criticism" and didn't connect it to light, happy events like classical Greek comedy.

Theatre

While puppet theater and religious plays were popular in the medieval Islamic world, live theatre and drama only became a big part of Arabic literature in modern times. There might have been older traditions, but they probably weren't seen as formal literature and weren't written down much. There's an old tradition among Shi'i Muslims of performing plays about the life and death of al-Husayn at the battle of Karbala in 680 CE. Also, Muḥammad Ibn Dāniyāl wrote several plays in the 13th century, mentioning that older plays were getting boring.

The most popular forms of theater in the medieval Islamic world were puppet theater (with hand puppets, shadow plays, and marionettes) and live religious plays called ta'ziya. In these, actors would re-enact events from Muslim history, especially the martyrdom of Ali's sons. Live non-religious plays were called akhraja, but they were less common.

Philosophical Novels

The Arab Islamic philosophers, Ibn Tufail and Ibn al-Nafis, were pioneers of the philosophical novel. They wrote the earliest novels that explored philosophical ideas. Ibn Tufail wrote the first Arabic novel, Hayy ibn Yaqdhan (Philosophus Autodidactus), as a response to Al-Ghazali's The Incoherence of the Philosophers. This was followed by Ibn al-Nafis who wrote Theologus Autodidactus as a response to Ibn Tufail's book. Both novels feature main characters who teach themselves and live alone on a desert island, making them early examples of "desert island stories."

However, while Hayy mostly lives alone, Kamil's story in Theologus Autodidactus goes beyond the island when he meets other people and returns to civilization. This makes it an early example of a coming of age story and even the first science fiction novel.

Ibn al-Nafis said his book Theologus Autodidactus defended Islam and its beliefs. He used logical arguments and hadith to prove his points. This work was later translated into Latin and English.

A Latin translation of Ibn Tufail's work, Philosophus Autodidactus, appeared in 1671. The first English translation was in 1708. These translations later inspired Daniel Defoe to write Robinson Crusoe, which also features a desert island story and is considered the first novel in English. Philosophus Autodidactus also influenced other European writers like John Locke and Gottfried Leibniz.

Science Fiction

Al-Risalah al-Kamiliyyah fil Sira al-Nabawiyyah (The Treatise of Kamil on the Prophet's Biography), known in English as Theologus Autodidactus, was written by the Arab scholar Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288). It is the earliest known science fiction novel. Besides being an early desert island and coming-of-age story, it includes science fiction elements like spontaneous generation, futurology, apocalyptic themes, the end of the world, and resurrection. Instead of using magic, Ibn al-Nafis tried to explain these events using his scientific knowledge in anatomy, biology, astronomy, and geology. His main goal was to explain Islamic religious teachings using science and philosophy. For example, he introduced his scientific theory of metabolism in this novel and referred to his discovery of pulmonary circulation to explain bodily resurrection.

Many stories within One Thousand and One Nights also have science fiction elements. For example, "The Adventures of Bulukiya" describes the main character's journey to find the herb of immortality. He explores seas, travels to the Garden of Eden and to Jahannam, and even journeys across the cosmos to different worlds much larger than his own. Along the way, he meets societies of jinns, mermaids, talking serpents, and talking trees. This story has elements of galactic science fiction.

In another Arabian Nights tale, Abdullah the Fisherman can breathe underwater and discovers an underwater society that is like an upside-down version of land society, where there's no money or clothes. Other Arabian Nights tales deal with lost ancient technologies and advanced civilizations that went wrong. "The City of Brass" features travelers on an archaeological trip to find an ancient lost city. They encounter a mummified queen, petrified people, lifelike humanoid robots, and a brass horseman robot that guides them. "The Ebony Horse" features a flying mechanical horse controlled by keys that can fly into outer space. These can be seen as early examples of proto-science fiction.

Other early Arabic proto-science fiction examples include al-Farabi's Opinions of the residents of a splendid city about a utopian society, and elements like the flying carpet.

Arabic Literature for Young Readers

Just like in other languages, more and more books are being written in Arabic for young readers. The Young Readers series from the New York University Press’s Library of Arabic Literature (LAL) offers both modern and classical texts in its Weaving Words collection. For example, it includes the 10th-century story collection Al-Faraj Ba’d al-Shiddah (Deliverance Follows Adversity) by Al-Muḥassin ibn ʿAlī al-Tanūkhī.

In 2011, author and translator Petra Dünges wrote about Arabic children's literature. She looked at books published between 1990 and 2010. She noticed that there's more variety in children's literature today, with books like the manga Gold Ring by Emirati writer Qays Sidqiyy. She also saw a growing demand for stories and pictures that take young readers seriously. She believes that Arabic children's literature is important for the development of Arab society and for keeping Arab culture and language alive.

Marcia Lynx Qualey, editor of the ArabLit online magazine, has translated Arabic novels for young readers, such as Thunderbirds by Palestinian writer Sonia Nimr. She also writes about Arabic books for teens. She and other translators run the website ArabKidLitNow!, which promotes translated Arabic literature for children and young readers.

Women in Arabic Literature

Even though women haven't always been highly recognized in Arabic literature throughout history, they have played a continuous role. Women's literature in Arabic hasn't been studied as much as it should be, and it's often not highlighted in Arabic education. This means its importance is probably underestimated.

The Medieval Period

In medieval times, women's poetry was not often included in general collections. However, some scholars believe that women poets might have been more active in early classical times than we realize.

Early women's poetry seemed to be mostly marathiya (elegy), which are poems of mourning. The earliest known poetesses were al-Khansa and Layla al-Akhyaliyyah in the 7th century. This suggests that elegies were a type of poetry that was acceptable for women to write. However, love poems were also important. During the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, there were professional singing slave girls (qiyan) who sang love songs and played music. Some famous Abbasid singing-girls included 'Inan and Arib al-Ma'muniyya. ‘Ulayya bint al-Mahdī, the half-sister of Caliph Harun al-Rashid, was also known for her poetry. The mystic and poet Rabi'a al-'Adawiyya was also famous. Women also played an important role as supporters of the arts.

Writings from medieval Islamic Spain mention several important female writers, especially Wallada bint al-Mustakfi (1001–1091), a princess who wrote Sufi poetry and was the lover of poet ibn Zaydun. Other poets include Hafsa Bint al-Hajj al-Rukuniyya and Nazhun al-Garnatiya bint al-Qulai’iya. These writers suggest a hidden world of literature by women.

Despite not being very prominent among the literary elite, women were important characters in Arabic literature. For example, Sirat al-amirah Dhat al-Himmah is an Arabic epic with a female warrior, Fatima Dhat al-Himma, as the main character. And Scheherazade is famous for cleverly telling stories in One Thousand and One Nights to save her life.

The Mamluk period saw the rise of the Sufi master and poet 'A'isha al-Ba'uniyya (died 1517). She was probably the most prolific female Arabic author before the 20th century. She wrote at least twelve books of prose and poetry, including over three hundred long mystical and religious poems.

Al-Nahda (Renaissance)

The earliest important female writer of the modern period, during the Arab cultural renaissance (Al-Nahda), was Táhirih (1820–52) from Iran. She wrote beautiful Arabic and Persian poetry.

Women's literary salons and societies in the Arab world also started in the 19th and early 20th centuries, mainly by Christian Arab women. They often had more freedom and access to education. Maryana Marrash (1848−1919) started what is believed to be the first salon in Aleppo that included women. In 1912, May Ziadeh (1886-1941) also started a literary salon in Cairo, and in 1922, Mary 'Ajami (1888−1965) did the same in Damascus. These salons helped women's writing (both literary and journalistic) and women's presses grow by allowing more interaction in the male-dominated world of Arab literature.

Late 20th Century to Early 21st Century

Since World War II, Arabic women's poetry has become much more prominent. Nazik Al-Malaika (1923–2007) is considered, along with Badr Shakir al-Sayyab, the founder of the Free Verse Movement in Arabic poetry. Her poetry is known for its different themes and use of imagery. She also wrote The Case of Contemporary Poets, which is an important work of Arab literary criticism.

Other major post-war female poets include Fadwa Touqan (Palestine, 1917–2003) and Salma Khadra Jayyusi (Palestine, 1926-).

The poetry of Saniya Salih (Syria, 1935–85) appeared in many famous magazines, but it was often overshadowed by her husband's work. Her later poems often talk about her relationship with her daughters and were written during her illness.

More recent Arabic literature has seen even more works published by female writers. Suhayr al-Qalamawi, Ulfat Idlibi, Layla Ba'albakki, and Alifa Rifaat are just some of these novelists and prose writers. There have also been many important female authors who wrote non-fiction, mainly exploring the lives of women in Muslim societies, such as Zaynab al-Ghazali, Nawal el-Saadawi, and Fatema Mernissi.

Women writers in the Arab world have sometimes faced controversy. For example, Layla Ba'albakki was accused of "endangering public morality" after publishing her short story collection Tenderness to the Moon (1963). The police even confiscated all copies of her book.

In Algeria, women's oral literature used in ceremonies called Būqālah became a symbol of national identity and resistance during the War of Independence in the 1950s and early 60s. These poems, usually four to ten lines long, covered topics from everyday life to politics. Since using Algerian Arabic as poetic language was an act of cultural resistance itself, these poems had a revolutionary meaning.

Contemporary Arabic Literature

Today, female Arab authors still risk controversy by discussing sensitive topics in their works. However, these themes are explored more openly and with more energy, thanks to social media and more international awareness of Arab literature. Current Arab female writers include Hanan al-Shaykh, Salwa al-Neimi (writer, poet, and journalist), and Joumana Haddad (journalist and poet).

Contemporary female Arab writers, poets, and journalists often take on an activist role to highlight and improve the lives of women in Arab society. This is seen in figures like Mona Eltahawy, an Egyptian columnist and public speaker known for her views on Arab and Muslim issues and her involvement in global feminism.

Modern Arab women's literature has also been greatly influenced by the Arab diaspora (Arabic speakers living in other countries). These writers produce works not only in Arabic but also in other languages like English, French, Dutch, and German. The Internet is also important for spreading literature produced in Arabic or Arabic-speaking regions. Younger poets especially use the Internet to share their work and create online collections.

Literary Criticism

For many centuries, there has been a lively culture of literary criticism in the Arabic-speaking world. In pre-Islamic poetry festivals, two poets would often compete, and the audience would decide the winner. Literary criticism also connects to religious studies, gaining official status with Islamic studies of the Qur'an. While modern literary criticism wasn't applied to the Qur'an (which was seen as unique), textual analysis, called ijtihad (independent reasoning), was allowed. This helped understand the message and develop critical methods for later work on other literature. A clear difference was often made between formal literary works and popular works, meaning only some Arabic literature was considered worthy of study.

Some of the first Arabic poetry analysis books were Qawa'id al-shi'r (The Foundations of Poetry) by Tha'lab (died 904) and Naqd al-shi'r (Poetic Criticism) by Qudamah ibn Ja'far. Other works continued the tradition of comparing two poets to see who followed classical poetic rules best. Plagiarism also became a big concern for critics. The works of al-Mutanabbi, considered by many to be the greatest Arab poet, were especially studied. His own pride sometimes made other writers look for sources for his verses. Just as there were collections of facts on many subjects, many collections detailing every possible rhetorical figure used in literature appeared, along with guides on how to write.

Modern criticism first compared new works unfavorably with old classical ideals, but these standards were soon seen as too strict. When European romantic poetry forms were adopted, new critical standards were introduced. Taha Hussayn, who knew a lot about European thought, even dared to examine the Qur'an with modern critical analysis, pointing out ideas and stories borrowed from pre-Islamic poetry.

Abdallah al-Tayyib (1921–2003) was an outstanding Sudanese scholar and literary critic. His most notable work is A Guide to Understanding Arabic Poetry, which took over 35 years to write and was published in four volumes.

Outside Views of Arabic Literature

Arabic literature has influenced people outside the Islamic world. One of the first important translations was Robert of Ketton's translation of the Qur'an in the 12th century. But it wasn't until the early 18th century that much of the diverse Arabic literature became known. This was largely thanks to scholars who studied Arabic, like Forster Fitzgerald Arbuthnot and his books such as Arabic Authors: A Manual of Arabian History and Literature.

Antoine Galland's French translation of the Thousand and One Nights was the first major Arabic work to become very successful outside the Muslim world. Other important translators included Friedrich Rückert and Richard Burton. Since at least the 19th century, Arabic works sparked a fascination in the West called Orientalism. Books with "foreign" morals were especially popular, but even these were sometimes censored for content, like references to homosexuality, which were not allowed in Victorian society. Most of the works chosen for translation often confirmed existing stereotypes about Arab cultures. Compared to the wide variety of literature written in Arabic, relatively few historical or modern Arabic works have been translated into other languages.

Since the mid-20th century, more Arabic books have been translated, and Arabic authors have started to gain recognition. Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz had most of his works translated after he won the 1988 Nobel Prize for Literature. Other writers, including Abdul Rahman Munif and Tayeb Salih, have received praise from Western scholars. Both Alaa Al Aswany's The Yacoubian Building and Rajaa al-Sanea's Girls of Riyadh got a lot of attention from Western media in the early 21st century.

See also

In Spanish: Literatura árabe para niños

In Spanish: Literatura árabe para niños

- Modern Arabic literature

- Copto-Arabic literature

- Arabic short story

- Riddles (Arabic)

- Arabic music

- Arabian mythology

- Literary Arabic

- Islamic Golden Age

- Arabic miniature

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |