Panchatantra facts for kids

The Panchatantra (pronounced Pan-cha-tan-tra) is a very old collection of stories from India. Its name means "Five Treatises" or "Five Books." These stories are mostly about animals that act like humans. They are written in both poetry and prose (regular writing). The stories are all connected within a larger "frame story," like Russian nesting dolls.

Experts believe the Panchatantra was written between 200 BCE and 300 CE. It was based on even older stories that people told each other. Some versions say a wise man named Vishnu Sharma wrote it. Other versions name Vasubhaga. These might be pen names, meaning they were not the authors' real names.

The Panchatantra is one of the most translated books from India. Its stories are known all over the world. You can find versions of it in almost every major language in India. There are also over 200 versions in more than 50 languages worldwide. One version even reached Europe in the 11th century.

Before the 1600s, the Panchatantra was available in Greek, Latin, Spanish, Italian, German, and English. Its influence spread from Java to Iceland. In India, the stories were rewritten, expanded, and translated many times. Many of its tales became part of everyday folklore.

The first known translation of the Panchatantra into a non-Indian language was in Middle Persian (Pahlavi) around 550 CE. This translation was done by a doctor named Borzuya. Later, this Persian version was translated into Syriac and then into Arabic in 750 CE. The Arabic version, called Kalīlah wa Dimnah, became very famous.

In Europe, the stories were often known as The Fables of Bidpai or The Morall Philosophie of Doni. Most European versions came from a Hebrew translation made in the 12th century.

Contents

Who Wrote It and When?

The introduction to the Panchatantra says an old wise man named Vishnusharma wrote it. It says he taught important lessons about good government to three princes. However, many scholars think Vishnusharma was not a real person. He was likely a character made up for the story.

Some versions of the text from South India and Southeast Asia say Vasubhaga wrote it. Most experts agree that the real author was likely a Hindu. The book does not favor one Hindu god over others. It respects many gods like Shiva and Indra.

No one knows for sure where the Panchatantra was first written. Some guess it was in Kashmir or South India. The original language was probably Sanskrit. The book has had different titles over time, like Tantrakhyayika or Panchakhyanaka. These names mean "little story" or "little story book."

The Panchatantra was translated into Pahlavi in 550 CE. This tells us it must have existed before that time. It also uses verses from another old Indian text called Arthasastra. This text was finished around the early centuries CE. Most scholars believe the Panchatantra was written around 300 CE. However, this is just an educated guess. Some of its animal stories are found in even older texts from 1000 BCE.

What's Inside the Panchatantra?

The Panchatantra is a collection of fables. Many of these stories use animals that act and talk like humans. These animals show human strengths and weaknesses. The main goal of the book is to teach nīti (pronounced nee-tee). Nīti means wise and sensible behavior in life. It's about how to live well and make good choices.

The book has a short introduction and then five main parts. Each part has a main story, called a frame story. Inside this main story, characters tell other stories. These "embedded stories" can even have more stories inside them. It's like a set of Russian dolls, where one story opens up to another. Besides the stories, the characters also share short, wise sayings to make their points.

Here are the five books and what they are about:

| Book Title | Meaning | What it Teaches |

| 1. Mitra-bheda | Breaking Up Friends | How friendships can be lost |

| 2. Mitra-lābha | Gaining Friends | The benefits of friendship |

| 3. Kākolūkīyam | Crows and Owls | Lessons about war and peace |

| 4. Labdhapraṇāśam | Losing What You Gained | How to avoid losing what you have |

| 5. Aparīkṣitakārakaṃ | Hasty Actions | Why you should think before you act |

Book 1: Losing Friends

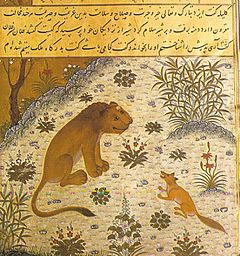

The first book is about a jackal named Damanaka. He is a clever but jobless minister in a lion's kingdom. Damanaka and his friend Karataka try to break up the friendships of the lion king. This book tells many fables about how close friends can become enemies.

This book is the longest, making up almost half of the whole work. It includes stories like "The Wedge-Pulling Monkey" and "Numskull and the Rabbit." These stories show how conspiracies and misunderstandings can ruin strong bonds.

Book 2: Winning Friends

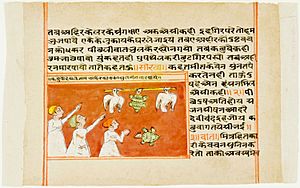

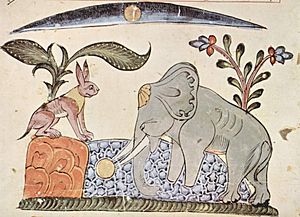

This book is different. It doesn't have stories inside stories as much. Instead, it follows the adventures of four friends: a crow, a mouse, a turtle, and a deer. These animals are all very different. The crow can fly, the mouse is tiny and lives underground, the turtle is slow and lives in water, and the deer is a land animal often hunted.

The main idea of this book is how important friendship and teamwork are. It teaches that even weak animals with different skills can achieve great things when they work together. By cooperating and supporting each other, they can overcome dangers and succeed. Stories include "The Mice That Set Elephant Free."

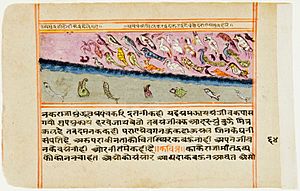

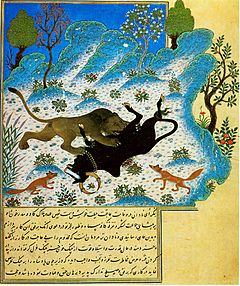

Book 3: Crows and Owls

This book talks about war and peace. It uses animal characters to show that cleverness and strategy can be more powerful than a large army. The story is about a war between crows and owls. Crows are seen as good and weaker, linked to daylight. Owls are seen as evil, stronger, and linked to night. The crow king listens to wise advice and wins. The owl king ignores good advice and loses.

The fables in this book also show that different characters have different needs. Understanding these needs can help create peaceful relationships. For example, one story tells of an old man who marries a young woman. She doesn't like him at first. One night, a thief enters their house. She gets scared and holds onto her husband for safety. This makes the old man happy, and he thanks the thief for bringing them closer.

This book includes stories like "The Cat's Judgment" and "The Brahmin the Thief and the Ghost."

Book 4: Losing What You Have

Book four is a simpler collection of fables with moral lessons. These stories teach you to be careful and not to lose what you already have. They warn against giving in to peer pressure or falling for tricky words. Unlike the first three books, which give positive examples, this book shows negative examples. It teaches you what to avoid and what to watch out for.

Stories in this book include "The Monkey and the Crocodile" and "The Ass in the Tiger-Skin." These fables highlight the dangers of carelessness and trusting the wrong people.

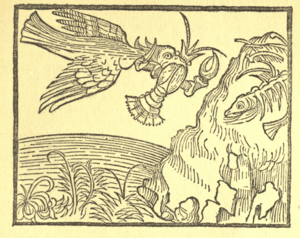

Book 5: Hasty Actions

Like book four, this last book is a collection of fables with moral lessons. It also shows negative examples and their bad results. The lessons here include: "get the facts first," "be patient," and "don't act too quickly and then regret it." It also warns against dreaming big without any real plan.

This book is special because most of its characters are humans, not animals. This might be because the author wanted to bring the reader from the fantasy world of talking animals back to the real human world.

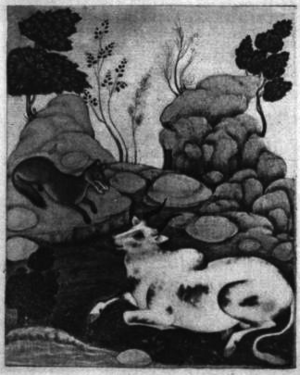

One famous story in this book is "The Loyal Mongoose." A woman leaves her baby with her pet mongoose. When she comes back, she sees blood on the mongoose's mouth. Thinking the mongoose killed her baby, she kills it. But then she finds her baby safe. She learns the mongoose killed a snake that was attacking her child. She regrets her hasty action.

How Panchatantra Stories Spread

The fables of Panchatantra are found in many languages around the world. They are thought to be part of the origin of many European stories. These include folk tales found in the works of Boccaccio, La Fontaine, and the Grimm Brothers.

For a while, people thought that all animal fables came from India and the Middle East. While this idea is no longer fully accepted, the Panchatantra was certainly one of the first books written for children. This means it had a huge impact on world literature, especially on fables and fairy tales.

Scholars have noticed that some Panchatantra stories are very similar to Aesop's Fables. For example, "The Ass in the Panther's Skin" is like Aesop's "The Ass in the Lion's Skin." "The Broken Pot" is similar to "The Milkmaid and Her Pail." Other well-known stories include "The Tortoise and The Geese" and "The Tiger, the Brahmin and the Jackal."

The French writer Jean de La Fontaine said that many of his fables were inspired by "Pilpay, an Indian Sage," which refers to the Panchatantra. The Panchatantra also influenced stories in Arabian Nights and Sindbad.

Why Was Panchatantra Written?

In India, the Panchatantra is known as a nītiśāstra. This means it's a book about "the wise conduct of life." It's like a guide to good behavior and political science. It uses ideas from older Indian texts about law and wealth.

Some scholars say nīti is about finding the most joy in life. It's about developing your strengths, being secure, successful, and having good friends and knowledge.

The Panchatantra shares many stories with the Buddhist Jataka tales. These tales were supposedly told by the Buddha himself. It's not clear if the Panchatantra borrowed from the Jataka tales, or if both drew from a common collection of old Indian stories. Many believe the tales were first told orally before being written down.

Some early Western scholars thought the Panchatantra was like Machiavelli's writings, focusing on cleverness and practical wisdom rather than strict morals. However, other scholars disagree. They see the stories as teaching dharma, or proper moral conduct. They believe the book promotes a down-to-earth, moral, and sensible way to learn from life's experiences.

The Panchatantra tells wonderful stories with wise sayings and timeless advice. It's a complex book that doesn't offer simple answers to life's challenges. It speaks to different readers in different ways. In India, it's seen as a guide to social ethics and smart behavior.

How the Stories Traveled

The Panchatantra took its current form between the 4th and 6th centuries CE. Buddhist monks traveling to India took the stories north to Tibet and China, and east to Southeast Asia. This led to versions in Tibetan, Chinese, Mongolian, Javanese, and Lao languages.

Borzuy's Journey to India

The Panchatantra also traveled to the Middle East through Iran. Around 550 CE, a famous doctor named Borzuya translated the book from Sanskrit into Pahlavi (Middle Persian). He named the main characters Karirak ud Damanak.

A story in the Shāh Nāma (The Book of the Kings) tells how Borzuy went to India. He was looking for a special herb that could bring the dead back to life. He didn't find the herb, but a wise man told him the herb was a metaphor. It meant that knowledge brings life to those who are uneducated. The wise man then showed him the Panchatantra. Borzuy translated it with the help of some Indian scholars.

Kalila wa Demna: Persian and Arabic Versions

Borzuy's Pahlavi translation of the Panchatantra arrived in Persia by the 6th century. This Middle Persian version is now lost. However, it became popular and was translated into Syriac and Arabic. The 8th-century Arabic translation by Abdullah Ibn al-Muqaffa called Kalīla wa Dimna was very important. It influenced many later translations into Greek, Hebrew, and Old Spanish.

Ibn al-Muqaffa's Kalīla wa Dimna is considered a masterpiece of Arabic writing. The two jackals from the Panchatantra became Kalila and Dimna in this version. Their names became so famous that the whole book was often called Kalila and Dimna.

Ibn al-Muqaffa' added new parts to his version. For example, he included a trial for Dimna, where the jackal is accused of causing the bull's death. Dimna is found guilty and put to death. Some scholars believe Ibn al-Muqaffa' used these stories to share his own political ideas in a hidden way.

How it Reached Europe

Most European translations of the Panchatantra came from this Arabic version. From Arabic, it was translated into Syriac, then into Greek in 1080. In 1252, it was translated into Spanish.

Perhaps the most important translation for Europe was into Hebrew by Rabbi Joel in the 12th century. This Hebrew version was then translated into Latin in 1480. This Latin book, called Directorium Humanae Vitae ("Directory of Human Life"), became the source for most European versions.

A German translation was printed in 1483. This made it one of the first books printed by Gutenberg's press after the Bible. The Latin version was translated into Italian in 1552. This Italian translation then became the basis for the first English translation in 1570.

Panchatantra Today

The Panchatantra has been studied by many scholars. They have worked to understand its history and how different versions came to be. Today, there are many modern translations available.

Arthur W. Ryder's translation from 1925 is still very popular. In the 1990s, new English translations by Chandra Rajan and Patrick Olivelle were published. These helped more people in the West discover this ancient classic.

The novelist Doris Lessing noted that while people today might know about other ancient Indian texts, they might not have heard of the Panchatantra. However, not long ago, it was well-known as a great Eastern classic. Its journey through history shows how unpredictable the fate of books can be.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Panchatantra para niños

In Spanish: Panchatantra para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |