The Guide for the Perplexed facts for kids

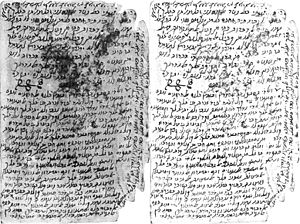

Maimonides' autograph draft of Dalālat al-ḥā'irīn, written in Standard Arabic with Hebrew script, from the Cairo Genizah

|

|

| Author | Moses Maimonides |

|---|---|

| Original title | דלאלת אלחאירין |

| Country | Ayyubid Empire |

| Language | Judeo-Arabic |

| Genre | Jewish philosophy |

|

Publication date

|

c. 1190 |

|

Published in English

|

1881 |

| Media type | Manuscript |

| 181.06 | |

| LC Class | BM545 .D3413 |

|

Original text

|

דלאלת אלחאירין at Script error: The function "name_from_code" does not exist. Wikisource |

| Translation | The Guide for the Perplexed at Wikisource |

The Guide for the Perplexed (Arabic: دلالة الحائرين, romanized: Dalālat al-ḥā'irīn, דלאלת אלחאירין; Hebrew: מורה נבוכים, romanized: Moreh Nevukhim) is a very important book about Jewish theology. It was written by a famous scholar named Maimonides. The book tries to connect the ideas of Aristotle (an ancient Greek philosopher) with traditional Jewish beliefs. It does this by finding logical explanations for many events described in religious texts.

Maimonides wrote this book in Classical Arabic, but he used the Hebrew alphabet. It was like a long, three-part letter to his student, Rabbi Joseph ben Judah of Ceuta. This book is our main source for understanding Maimonides' philosophical ideas. It's different from his writings on Jewish law. A few people thought the Guide was written by someone else, but most scholars agree Maimonides wrote it.

The book's ideas, like how philosophy and religion fit together, are important beyond just Judaism. Because of this, it became Maimonides' most famous work outside the Jewish world. It even influenced many well-known non-Jewish philosophers. After it was published, almost every philosophical book in the Middle Ages mentioned or discussed Maimonides' views. Within Judaism, the Guide became very popular. Many Jewish communities wanted copies. However, it was also quite controversial, and some communities limited its study or even banned it.

Contents

About the Book's Creation

The Guide for the Perplexed was written by Maimonides between 1185 and 1190. He wrote it in Classical Arabic using Hebrew letters. The first translation into Hebrew was made in 1204 by Samuel ibn Tibbon. The book is divided into three main parts.

Maimonides explained that he wrote the Guide to help religious people. He wanted to help those who believed in their faith and followed its duties, but also studied philosophy. He wanted to show them how these two areas could work together.

This work has also a second object in view: It seeks to explain certain obscure figures which occur in the Prophets, and are not distinctly characterized as being figures. Ignorant and superficial readers take them in a literal, not in a figurative sense. Even well-informed persons are bewildered if they understand these passages in their literal signification, but they are entirely relieved of their perplexity when we explain the figure, or merely suggest that the terms are figurative. For this reason I have called this book Guide for the Perplexed.

He also explained ancient Jewish mystical texts. These included Maaseh Bereishit (about the creation story in Book of Genesis) and Merkabah mysticism (about the chariot vision in the Book of Ezekiel). These are two important mystical texts in the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible). Maimonides discusses these in the third book. The first two books prepare the reader with the philosophical knowledge needed to understand these deeper mystical ideas.

Book One: Understanding God

The first book starts with Maimonides' main idea about God. He explains that God is one, everywhere, and has no physical body. He says that when the Bible describes God using human terms, like the "hand of God," these are not meant to be taken literally. They are figures of speech.

Maimonides believed it was wrong for people to think God has a body. To explain this, he spent many chapters analyzing Hebrew words used to describe God. He showed that these words have different meanings when used for physical things versus when used for God. He argued that the Bible itself shows God is not physical.

Maimonides believed that we cannot describe God using positive terms, like "God is mighty" in a physical sense. Instead, we can only describe God using negative terms. For example, we can say God is "not physical," "not limited by time," or "does not change." These negative descriptions help us understand what God is not, without making wrong assumptions.

Thinking of God as having a body or positive human traits was seen as a serious mistake. It was like idolatry because it misunderstood God's true nature.

The first book also explains why deep philosophical and mystical topics are taught later in Jewish tradition. Maimonides thought that most people could not understand these ideas without proper learning. Approaching them without enough knowledge of the Torah and other Jewish texts could lead to wrong beliefs.

The book ends with Maimonides' thoughts on the ideas of Jewish Kalam and Islamic Kalam. These were schools of thought that used reason to prove religious beliefs. Maimonides agreed with their conclusions about God's unity and creation. However, he disagreed with some of their methods and arguments, finding them weak.

Book Two: The Universe and Prophecy

This book begins by discussing 26 ideas from Aristotle's metaphysics. Maimonides accepted 25 of these as proven. He only disagreed with the idea that the universe has always existed.

Maimonides describes the physical structure of the universe as he understood it. This view was mostly based on Aristotle's ideas. It included a spherical Earth at the center, surrounded by Heavenly Spheres. While he rejected Aristotle's view on the universe's eternity, Maimonides used Aristotle's proofs for God's existence. He also used concepts like the Prime Mover, which is the first cause of all motion.

A new idea Maimonides brought up was connecting natural forces and heavenly spheres with the concept of an angel. He saw them as the same thing. The Spheres are like pure intelligences that get power from the Prime Mover. This energy flows from one sphere to the next, eventually reaching Earth.

This leads to a discussion about whether the universe is eternal or was created. Maimonides thought Aristotle's theory of an eternal universe was the best philosophical argument. However, he believed that Divine Revelation from the Torah provided the extra information needed to know that the universe was created. He then briefly explains creation as described in Genesis.

The second main part of this book is about prophecy. Maimonides had a unique view. He stressed the intellectual side of prophecy. He believed that prophecy happens when a prophet has a vision and then uses their intellect to understand it. Many descriptions of prophecy in the Bible are metaphors. All stories of God speaking with a prophet, except for Moses, are metaphors for understanding a vision. Maimonides said that all prophecy, except Moses', happens through natural laws.

Maimonides describes 11 levels of prophecy. Moses' prophecy was the highest and clearest. Lower levels involved more indirect ways of receiving messages, like through angels or dreams.

Book Three: Morality and Laws

The third book starts with a deep explanation of the mystical passage of the Chariot from the Book of Ezekiel. This passage was traditionally considered very sensitive in Jewish law. It was not supposed to be taught directly. Students were expected to understand hints from their teachers. Maimonides, however, provides more direct explanations.

He then explains basic mystical ideas using Biblical terms for Spheres, elements, and Intelligences. Even here, he still uses some indirect language.

Next, Maimonides analyzes the moral aspects of the universe. He discusses the problem of evil, explaining that people are responsible for evil because of free will. He also talks about trials and tests, like those of Job and the story of the Binding of Isaac. He explains concepts like providence (God's care for the world) and omniscience (God knowing everything). Maimonides believed that evil is not something God creates. Instead, evil is a lack of good, and it often comes from humans themselves.

Maimonides then explains his reasons for the 613 mitzvot, which are the 613 laws in the five books of Moses. He divides these laws into 14 sections, similar to his other work, the Mishneh Torah. He offers a more practical approach to understanding the purpose of these commandments. For example, he explains that sacrifices helped the Israelites move away from idolatry.

The book concludes with the idea of living a perfect and balanced life. This life is based on correctly worshipping God. Maimonides believed that having a correct philosophical understanding of Judaism, as explained in the Guide, is key to true wisdom.

Translations of the Guide

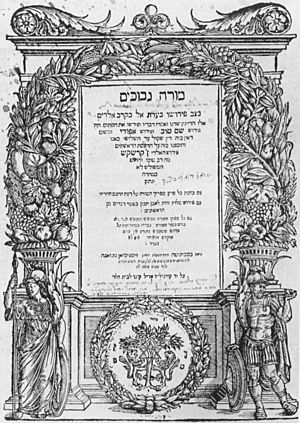

The original book was written in Judaeo-Arabic. The first Hebrew translation, called Moreh HaNevukhim, was made in 1204 by Samuel ben Judah ibn Tibbon. This Hebrew version was used for many centuries.

The first full Latin translation was printed in Paris in 1520. A French translation came out in 1856.

The first complete English translation was The Guide for the Perplexed by Michael Friedländer in 1881. It was known for being very faithful to the original text. Another popular English translation was made by Shlomo Pines in 1963.

Today, there are translations in many languages, including Yiddish, French, Polish, Spanish, German, Italian, Russian, and Chinese.

Important Manuscripts

Old copies of Maimonides' Guide for the Perplexed are very valuable. The earliest complete copy in Judeo-Arabic was made in Yemen in 1380. It is now kept at the British Library.

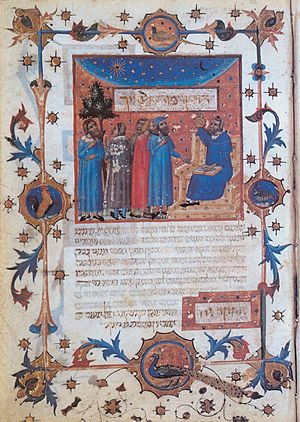

Another important manuscript, copied in 1396, was found in Yemen by David Solomon Sassoon. It is now at the University of Toronto. This copy has an introduction by Samuel ibn Tibbon and is almost complete. It has 496 pages with many beautiful drawings.

The Bodleian Library at Oxford University has at least fifteen incomplete copies and fragments of the original Arabic text. Many other university and state libraries also have Hebrew translations made by Samuel ibn Tibbon and Yehuda Alharizi.

See also

In Spanish: Guía de los Perplejos para niños

In Spanish: Guía de los Perplejos para niños

- David ibn Merwan al-Mukkamas

- Baruch Spinoza

- Jewish philosophy

- Kabbalah

- Mario Javier Saban

- Nachmanides

- Yonah of Gerona

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |