Medicine in the medieval Islamic world facts for kids

Islamic medicine is also known as Arabian medicine. It refers to the medical knowledge that grew in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age. Most of these writings were in Arabic, which was the main language of learning at the time.

Islamic medicine built upon and improved the medical ideas from ancient times. This included the teachings of famous Greek doctors like Hippocrates, Galen, and Dioscorides. During the medieval period, medicine in the Middle East was the most advanced in the world. It combined ideas from Greek, Roman, Mesopotamian, Persian, and Indian medicine. Islamic scholars also made many new discoveries. Later, this knowledge, along with ancient Greek medicine, was brought to Europe during the Renaissance of the 12th century.

Doctors in the Islamic world were highly respected for many centuries. Their ideas and textbooks were used widely until modern science began to change medicine. Even today, some of their writings are still interesting to doctors.

Contents

- A Look at Islamic Medicine

- History and Beginnings

- How Medicine Was Practiced

- Important Doctors and Scientists

- Medical Discoveries

- Surgery

- Medical Ethics

- Hospitals

- Medical Education

- Pharmacy

- Women and Medicine

- Role of Christians

- Legacy

- See also

A Look at Islamic Medicine

Medicine was a very important part of Islamic culture during the medieval period. This time, from the 700s to the 1300s, is often called the Islamic Golden Age. The kind of medical care a person received often depended on their wealth and social standing.

Islamic doctors and scholars wrote many detailed medical books. They explored, analyzed, and combined different medical theories and practices. Early Islamic medicine was based on traditions from Arabia during the time of Muhammad. It also used knowledge from Hellenistic medicine (like Unani), ancient Indian medicine (like Ayurveda), and ancient Iranian Medicine from the Academy of Gundishapur. The works of ancient Greek and Roman doctors like Hippocrates, Galen, and Dioscorides also had a big impact. During this Golden Age, there was a great desire for knowledge. Scholars worked hard to find, organize, and improve classical learning. This made Arab science the most advanced of its time. Ophthalmology (eye medicine) was especially strong, with the work of Ibn al-Haytham being important for hundreds of years.

History and Beginnings

Prophetic Medicine

When Islamic society was new, people wanted to make sure that using medical knowledge from other cultures fit with Islamic beliefs. Studying and practicing medicine was seen as a good deed, based on faith and trust in God.

The Prophet not only told sick people to take medicine, but he himself invited expert doctors for this purpose.

Muhammad's ideas about health and healthy living were collected in books called Ṭibb an-Nabī ("The Medicine of the Prophet"). In the 1300s, Ibn Khaldun wrote that illnesses often come from what we eat. He quoted Muhammad saying: "The stomach is the House of Illness, and abstinence is the most important medicine. The cause of every illness is poor digestion."

The Sahih al-Bukhari, a collection of Muhammad's sayings, mentions his views on medicine. For example, it talks about Muhammad preferring not to use cauterization (burning skin to stop bleeding) and asking for other treatments. There are also stories of ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān fixing his teeth with gold wire. Cleaning teeth with a small wooden stick was also a habit from before Islam.

"Prophetic medicine" was not often mentioned by the main Islamic medical writers. However, its ideas about remedies and plants continued for centuries.

Early Doctors in Islam

In the early days of Islam, Arabian doctors likely learned about Greek and Roman medicine by meeting doctors in the newly conquered lands. They probably didn't read many original books at first. Moving the capital to Damascus helped with this, as Syrian medicine was part of that old tradition. We know of two Christian doctors: Ibn Aṯāl, who worked for the ruler Muawiyah I, and Abu l-Ḥakam, who prepared medicines. Their families continued to serve later rulers.

These examples show that doctors in the early Islamic society already knew about classical medical traditions. This knowledge likely came from Alexandria and was brought by Syrian scholars or translators.

Medicine in the Islamic Period

Islamic medicine grew during the Middle Ages (around 650–1500 AD). It had a huge impact on people's health and laid the groundwork for modern medicine. It influenced European medicine and still affects medical practices today.

Learning from Older Traditions (7th–9th Century)

Not many records tell us exactly how Islamic society gained medical knowledge. One doctor, Abdalmalik ben Abgar al-Kinānī, is said to have worked at the medical school of Alexandria before joining the court of ʿUmar ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz. ʿUmar moved the medical school from Alexandria to Antioch. People from the Academy of Gondishapur also traveled to Damascus.

An important book from the late 700s is Jabir ibn Hayyan's "Book of Poisons." He mentioned older works that were translated into Arabic, including those by Hippocrates, Plato, Galen, and Aristotle. He also listed Persian names for some drugs and plants.

In 825, the ruler Al-Ma'mun started the House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikma) in Baghdad. It was like the Academy of Gondishapur. Under the leadership of the Christian doctor Hunayn ibn Ishaq, and with help from the Byzantine Empire, all available ancient texts were translated. This included works by Galen, Hippocrates, Plato, Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Archimedes.

Today, we understand that early Islamic medicine mostly came from Greek sources translated from the Academy of Alexandria into Arabic. The influence of Persian medicine seems to have been more about the types of medicines and plants used.

Ancient Greek, Roman, and Hellenistic Texts

Many translations of ancient medical texts were made from the 600s onwards. Hunayn ibn Ishaq was key in translating almost all known classical medical books at the House of Wisdom in Baghdad. Ruler Al-Ma'mun even asked the Byzantine emperor for classical texts. This led to the translation of major medical works by Hippocrates and Galen into Arabic. Other works by Pythagoras, Dioscorides, and many more were also translated.

The works of Oribasius, a Roman doctor from the 300s AD, were well known and often quoted by Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (Rhazes). The writings of Paul of Aegina, who lived in Alexandria during the Arab expansion, were also very important for early Islamic doctors. He connects late Hellenistic and early Islamic medical science.

Arabic Translations of Hippocrates

Early Islamic doctors knew about Hippocrates and that his life story was partly a legend. They also knew that several people named Hippocrates existed, and their works were collected under one name. Ibn an-Nadīm wrote a short paper about "the (various persons called) Hippokrates." Translations of some of Hippocrates's works existed before Hunayn ibn Ishaq started his translations. The historian Al-Yaʾqūbī made a list of known works in 872, including summaries or full texts. The philosopher Al-Kindi wrote a book called at-Tibb al-Buqrati (The Medicine of Hippocrates). Rhazes was the first Arabic doctor to use Hippocrates's writings to build his own medical system. Hippocrates's work was studied and commented on throughout the Middle Ages in Islamic medicine.

Arabic Translations of Galen

Galen was one of the most famous scholars and doctors of ancient times. Some of his original writings and life details are now lost, but we know about them because they were translated into Arabic. Jabir ibn Hayyan often quoted Galen's books, which were available in early Arabic translations. Hunayn ibn Ishaq and his student Tabit ben-Qurra were very important for translating and explaining Galen's work. They also tried to create a complete medical system from these works. However, doctors like Jabir ibn Hayyan and Rhazes began to question some of Galen's ideas. In the 900s, the doctor 'Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi wrote:

Galen wrote many works, but each only covers a part of medicine. There are long sections and repeated ideas. [...] None of them can be seen as complete.

Syrian and Persian Medical Texts

Syrian Texts

In the 900s, Ibn Wahshiyya collected writings from the Nabataeans, which included medical information. The Syrian scholar Sergius of Reshaina translated works by Hippocrates and Galen. Hunayn ibn Ishaq later translated these into Arabic. An early translation from Syrian was the Kunnāš by Ahron, translated into Arabic by Māsarĝawai al-Basrĩ in the 600s. Syrian doctors also played a big role at the Academy of Gondishapur and worked for the Abbasid caliphs.

Persian Texts

The Academy of Gondishapur was important for sharing Persian medical knowledge with Arab doctors. Founded by the Sassanid ruler Shapur I in the 200s AD, this academy connected ancient Greek and Indian medical traditions. Arab doctors trained there may have helped link these traditions with early Islamic medicine. The book Abdāl al-adwiya by the Christian doctor Māsarĝawai is important because it starts by saying:

These are the medications which were taught by Greek, Indian, and Persian physicians.

In his book Firdaus al-Hikma (The Paradise of Wisdom), Al-Tabari used few Persian medical terms for diseases. However, he used many Persian names for drugs and herbs, which became part of Islamic medical language. Rhazes also rarely used Persian terms and only mentioned two Persian books.

Indian Medical Texts

Indian scientific works, like those on Astronomy, were translated into Arabic as early as the 700s. By the time of Harun al-Rashid, Indian books on medicine and pharmacology were being translated. Ibn al-Nadim mentioned three translators of Indian works: Mankah, Ibn Dahn, and ʾAbdallah ibn ʾAlī. Yūhannā ibn Māsawaiyh quoted an Indian textbook in his book on eye medicine.

Al-Tabarī dedicated 36 chapters of his Firdaus al-Hikmah to Indian medicine. He quoted Sushruta, Charaka, and the Ashtanga Hridaya, an important book on Ayurveda. Rhazes also quoted Sushruta and Charaka in his works.

It is thought that Indian medicine, like Persian medicine, mostly influenced the types of medicines and herbs used in Arabic medicine. This is because many Indian names for herbal medicines were used that were unknown in Greek medicine. Persian doctors, possibly from the Academy of Gondishapur, were likely the first to connect Indian and Arabic medicine. More recent studies show that many Ayurvedic texts were translated into Persian in South Asia from the 1300s. From the 1600s, many Hindu doctors learned Persian and wrote medical texts combining Indian and Muslim medical ideas.

How Medicine Was Practiced

Medicine in the medieval Islamic world was often connected to growing plants. Fruits and vegetables were seen as important for health, though their properties were understood differently than today. The idea of humoral theory was also a big part of medicine. This theory shaped how doctors diagnosed and treated patients. This type of medicine was very holistic, focusing on a person's daily routine, environment, and diet. So, each patient received different advice based on their illness and lifestyle. Treatments were based on whether a person's "humors" were hot, cold, melancholic, or choleric.

Using Plants in Medicine

Using plants for medicine was very common. Most plants were thought to have both benefits and risks, and were used in specific situations.

Important Doctors and Scientists

The ideas of great doctors and scientists from the Islamic Golden Age shaped medicine for many centuries. Their thoughts on medical ethics are still discussed today, especially in Islamic countries. Their ideas about how doctors should act and the doctor–patient relationship are seen as good examples even now.

Imam Ali ibn Musa al-Rida

Ali ibn Musa al-Rida (765–818) was an important religious leader. His book "Al-Risalah al-Dhahabiah" ("The Golden Treatise") talks about medical cures and staying healthy. It was dedicated to the ruler Ma'mun. At the time, it was seen as a very important medical book. It was called "the golden treatise" because Ma'mun ordered it to be written in gold ink. In his work, Al-Ridha was influenced by the idea of humoral medicine.

Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari

The first medical encyclopedia in Arabic was Firdous al-Hikmah ("Paradise of Wisdom") by Persian scientist Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari. Written around 860, it had seven parts and was dedicated to the ruler al-Mutawakkil. His encyclopedia was influenced by Greek sources like Hippocrates, Galen, Aristotle, and Dioscurides. Al-Tabari was a pioneer in child development. He stressed the strong links between psychology and medicine, and the need for psychotherapy and counseling for patients. His book also discussed the influence of Sushruta and Charaka on medicine, including mental health treatments.

Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi

'Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi (died 994 AD), also known as Haly Abbas, was famous for his book Kitab al-Maliki, translated as Complete Book of the Medical Art or The Royal Book. This book was one of the great classical works of Islamic medicine. It did not include magical or astrological ideas. It was translated and used as a surgery textbook in European schools. The Royal Book was as famous as Avicenna's Canon for centuries. One of Haly Abbas's biggest contributions was his description of how blood moves through tiny vessels (capillaries).

Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (Rhazes)

Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (Latin name: Rhazes) (born 865) was one of the most talented scientists of the Islamic Golden Age. Born in Persia, he was a doctor, alchemist, and philosopher. He is most famous for his medical works, but he also wrote about plants, animals, physics, and math. His work was highly respected. Many of his books were translated into Latin, and he was a leading authority in European medicine until the 1600s.

In his medical ideas, al-Razi mostly followed Galen. However, he paid special attention to each patient, saying that everyone needed individual treatment. He also focused on hygiene and diet, which showed ideas from the Hippocratic school. Rhazes thought about how climate and seasons affected health. He made sure patients' rooms had clean air and good temperatures. He also understood the importance of preventing illness and making careful diagnoses.

At the start of an illness, choose treatments that do not weaken the [patient's] strength. [...] If a change in diet is enough, do not use medicine. If single drugs are enough, do not use mixed drugs.

The Comprehensive Book of Medicine

The Kitab-al Hawi fi al-tibb (al-Hawi, Latin name: The Comprehensive book of medicine) was one of al-Razi's biggest works. It was a collection of medical notes he made throughout his life. It included extracts from his readings and observations from his own medical practice. The published version has 23 volumes. Al-Razi quoted Greek, Syrian, Indian, and earlier Arabic works. He also included medical cases from his own experience. Each volume dealt with specific body parts or diseases.

Al-Hawi remained an important medical textbook in many European universities. It was seen as the most complete medical work written by a scientist until the 1600s. It was first translated into Latin in 1279.

The Book for Al-Mansur

The al-Kitab al-Mansuri (Latin name: Liber almansoris) was dedicated to a ruler named Abu Salih al-Mansur ibn Ishaq. This book is a full encyclopedia of medicine in ten parts. The first six parts cover medical theory, like anatomy, how the body works, diseases, medicines, health, diet, and cosmetics. The other four parts describe surgery, poisons, and fever. The ninth part, which discusses diseases by body part, was very popular in Europe.

This book was first translated into Latin in 1175. It was printed many times in Venice in the late 1400s.

The Royal Book

Another work by al-Razi is called the Kitab Tibb al-Muluki (Regius). This book talks about treating diseases through diet. It is thought to have been written for rich people who often ate too much and got stomach problems.

Smallpox and Measles

Al-Razi's book on smallpox and measles was considered the earliest detailed book on these infections. His careful descriptions of the first symptoms, how the diseases progressed, and the treatments he suggested are seen as a masterpiece of Islamic medicine.

Abu-Ali al-Husayn ibn Abdullah ibn-Sina (Avicenna)

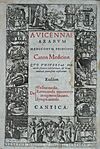

Right image: The Canon of Medicine, printed in Venice in 1595.

Ibn Sina, known in the West as Avicenna, was a Persian scholar and doctor from the 900s and 1000s. He was famous for his scientific works, especially his medical writings. He is sometimes called the "Father of Early Modern Medicine." Avicenna made many medical observations and discoveries. He recognized that diseases could spread through the air. He also understood many mental health conditions. He suggested using forceps during difficult births. He could tell the difference between different types of facial paralysis. He also described guinea worm infection and trigeminal neuralgia (a type of facial pain). He wrote two important medical books: his most famous, al-Canon fi al Tibb (The Canon of Medicine), and The Book of Healing.

Avicenna's medicine became very important through his famous book The Canon of Medicine. This book was used as a textbook for medical students and teachers. It is divided into five volumes:

- The first volume covers basic medical rules.

- The second is a guide to different medicines.

- The third describes diseases specific to body organs.

- The fourth discusses diseases affecting the whole body and ways to prevent illness.

- The fifth describes mixed medicines.

The Canon was very influential in medical schools and for later medical writers.

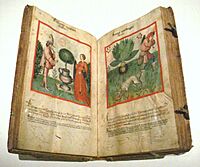

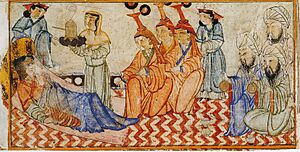

Ibn Buṭlān

Ibn Buṭlān was an Arab doctor who worked in Baghdad during the Islamic Golden Age. He is known for his book Taqwim al-Sihhah (The Maintenance of Health), which is best known in the West by its Latin name, Tacuinum Sanitatis.

This book talked about hygiene, dietetics (how food affects health), and exercise. It stressed the benefits of taking care of one's physical and mental well-being regularly. The book's popularity for centuries shows how much Arabic culture influenced early modern Europe.

Medical Discoveries

Human Body and How It Works

It is believed that Ibn al-Nafis made an important discovery about human anatomy and how the body works. However, it's doubtful he did this by dissecting human bodies. He said he avoided dissection because of religious rules and his "compassion" for the human body.

Doctors used to think that blood flowed from the right side of the heart to the left side through invisible passages in the wall between them. But in the 1200s, Ibn al-Nafis, a Syrian doctor, found this was wrong. He discovered that the wall between the heart's ventricles was solid, with no passages. Ibn al-Nafis found that blood from the right side of the heart actually travels to the lungs and then to the left side. This was one of the first descriptions of pulmonary circulation (blood flow through the lungs). His writings were only rediscovered in the 1900s. William Harvey later made the same discovery independently and made it widely known.

Ancient Greeks thought vision happened because a "visual spirit" came out of the eyes. But in the 1000s, the Iraqi scientist Ibn al-Haytham, also known as Al-hazen, developed a new idea about human vision. He explained that the eye was like an optical instrument. His description of the eye's parts helped him create his theory of how images are formed. This involves light rays bending as they pass through different parts of the eye. Ibn al-Haytham developed his theory through experiments. In the 1100s, his Book of Optics was translated into Latin and was studied in both the Islamic world and Europe until the 1600s.

Ahmad ibn Abi al-Ash'ath, a famous doctor from Iraq, described how the stomach works in a live lion in his book. He wrote:

When food enters the stomach, especially when it is plentiful, the stomach dilates and its layers get stretched...onlookers thought the stomach was rather small, so I proceeded to pour jug after jug in its throat…the inner layer of the distended stomach became as smooth as the external peritoneal layer. I then cut open the stomach and let the water out. The stomach shrank and I could see the pylorus…

Ahmad ibn Abi al-Ash'ath observed the stomach of a live lion in 959. This description happened almost 900 years before William Beaumont made similar observations. This makes Ahmad ibn al-Ash'ath the first person to do experiments on how the stomach works.

According to Galen, the lower jaw had two parts that joined in the middle. But Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi, while visiting Egypt, saw many skeletons of people who had died from hunger. He examined them and found that the mandible (lower jaw) is made of one piece, not two. He wrote:

All anatomists agree upon that the bone of the lower jaw consists of two parts joined together at the chin. [...] The inspection of this part of the corpses convinced me that the bone of the lower jaw is all one, with no joint nor suture. I have repeated the observation a great number of times, in over two hundred heads [...] I have been assisted by various different people, who have repeated the same examination, both in my absence and under my eyes.

Al-Baghdadi's discovery didn't get much attention at the time. This was because his findings were hidden within a detailed book about Egypt's geography, plants, monuments, and the famine.

Modern Islamic Medicine

Today, the history of Islamic medicine is sometimes overlooked in medical education. The International Institute of Islamic Medicine was created to share the history and knowledge of Islamic medicine in North America. Bringing back old Islamic medical traditions could be helpful in today's medical practice.

Surgery

The growth of hospitals in ancient Islamic society helped surgery develop. Doctors knew about surgical procedures from older texts that described them. Translations of pre-Islamic medical books were a key foundation for doctors and surgeons. Surgery was not often performed because the success rate was very low, even though older records showed good results for some operations. Many different types of procedures were done in ancient Islam, especially for eye problems.

Surgical Techniques

Bloodletting and cauterization were widely used by doctors in ancient Islamic society to treat patients. These two techniques were common because they could treat many different illnesses. Cauterization, which involves burning the skin or flesh of a wound, was done to prevent infection and stop heavy bleeding. To do this, doctors heated a metal rod and used it to burn the wound. This would make the blood clot and help the wound heal.

Bloodletting, the removal of blood, was used to get rid of "bad humors" that were thought to cause illness. A phlebotomist would drain blood directly from veins. "Wet" cupping was another form of bloodletting. A small cut was made in the skin, and a heated cup was placed over it to draw out blood. The heat and suction made the blood rise to the surface to be drained. "Dry cupping" involved placing a heated cup (without a cut) on a painful area to relieve pain or itching. Even though these procedures seemed simple, doctors sometimes had to pay compensation if they caused injury or death due to carelessness. Both cupping and bloodletting were considered helpful for sick patients.

Eye Treatments

Surgery was important for treating eye problems like trachoma and cataracts. A common problem for trachoma patients is when blood vessels grow into the cornea of the eye. Ancient Islamic doctors thought this caused the disease. The surgical technique to fix this is called peritomy today. It involved using an instrument to keep the eye open, tiny hooks to lift tissue, and a very thin scalpel to cut it away. A similar technique was used for pterygium, which is a triangular growth on the eye. This was lifted with hooks and cut with a small knife. Both procedures were very painful for the patient and difficult for the doctor.

In medieval Islamic writings, cataracts were thought to be caused by a membrane or cloudy fluid between the lens and the pupil. The method for treating cataracts (called couching) was known from older translated books. A small cut was made in the sclera (white part of the eye) with a lancet. A probe was then inserted to push the lens to one side of the eye. After the procedure, the eye was washed with salt water and bandaged with cotton soaked in rose oil and egg whites. Patients had to lie on their back for several days to prevent the cataract from moving back.

Pain Relief and Preventing Infection

In both modern and medieval Islamic surgery, anaesthesia (pain relief) and antisepsis (preventing infection) are important. Before these were developed, surgery was limited to broken bones, dislocations, injuries needing amputation, and urinary problems. Ancient Islamic doctors tried to prevent infection. For example, they washed patients before a procedure. After surgery, the area was often cleaned with "wine, wine mixed with oil of roses, oil of roses alone, salt water, or vinegar water." These liquids have properties that help prevent infection. Various herbs and resins like frankincense and myrrh were also used. Drugs like "henbane, hemlock, soporific black nightshade, lettuce seeds" were used to treat pain. Some of these drugs caused drowsiness. Some modern scholars think these drugs were used to make a person unconscious before an operation, like modern anesthetics. However, there is no clear record of this use before the 1500s.

Islamic scholars introduced mercuric chloride to clean wounds.

Medical Ethics

Doctors like al-Razi wrote about the importance of good behavior in medicine. He, along with Avicenna and Ibn al-Nafis, may have introduced the first ideas of ethics in Islamic medicine. Al-Razi wrote a book called "Kitab al-tibb al-ruhani" ("Book on Spiritual Physick") about general ethics. He believed that a doctor should not only be skilled but also a good role model. His ideas on medical ethics covered three areas: the doctor's responsibility to patients, to themselves, and the patients' responsibility to doctors.

The oldest surviving Arabic book on medical ethics is Ishaq ibn 'Ali al-Ruhawi's Adab al-Tabib ("Morals of the physician"). It was based on the works of Hippocrates and Galen. Al-Ruhawi believed that doctors were "guardians of souls and bodies." He insisted that they use proper medical manners for strong ethics and not ignore the theory behind medicine.

Islamic medical ethics can be found in two types of writings: Adab literature and classic Islamic legal tradition. Adab literature promotes universal good qualities and manners that apply to everyone, regardless of their religion or culture. Islamic legal traditions are based on Islamic laws and are used when there are ethical problems, such as in biomedical issues.

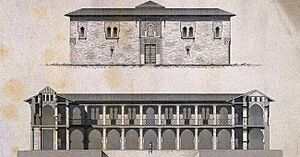

Hospitals

Many hospitals were built during the early Islamic era. They were called Bimaristan or Dar al-Shifa, which mean "house of the sick" and "house of curing" in Persian and Arabic. The idea of a hospital as a place to care for sick people came from the early rulers. The first Muslim hospital service was in the courtyard of the Prophet's mosque in Madinah. During a battle, Muhammad ordered a tent to be set up to provide medical care for wounded soldiers. Over time, rulers expanded traveling hospitals to include doctors and pharmacists.

The ruler Al-Walid ibn Abd al-Malik is often credited with building the first bimaristan in Damascus in 707 AD. This hospital had paid doctors and a well-equipped pharmacy. It treated the blind, people with leprosy, and other disabled people. It also separated patients with leprosy from others. Some people think this was more like a place for lepers than a full hospital. The first true Islamic hospital was built during the rule of Harun al-Rashid (786–809 AD). He invited a chief doctor's son to lead the new Baghdad bimaristan. It quickly became famous and led to more hospitals being built in Baghdad.

Hospital Features

As hospitals grew in Islamic civilization, they developed specific features. Bimaristans were open to everyone, no matter their race, religion, country, or gender. Documents stated that no one should ever be turned away. The main goal of all doctors and staff was to help patients get well. There was no limit to how long a patient could stay; hospitals had to keep patients until they fully recovered. Men and women were admitted to separate but equally equipped wards. These wards were further divided for mental illness, contagious diseases, non-contagious diseases, surgery, general medicine, and eye diseases. Patients were cared for by nurses and staff of the same gender. Each hospital had a lecture hall, kitchen, pharmacy, library, mosque, and sometimes a chapel for Christian patients. Fun activities and musicians were often used to comfort and cheer up patients.

Hospitals were not just for treating patients; they also served as medical schools to teach students. Basic science was learned through private tutors, self-study, and lectures. Islamic hospitals were the first to keep written records of patients and their treatments. Students were responsible for these records, which doctors later edited and used for future treatments.

During this time, doctors had to get a license to practice in the Abbasid Caliphate. In 931 AD, a ruler learned that someone died because of a doctor's mistake. He ordered that doctors could not practice until they passed an exam. From then on, licensing exams were required, and only qualified doctors could practice medicine.

Medical Education

Medieval Islamic cultures had different ways of teaching medicine before there were official schools. Many future doctors learned from family members or by working with experienced doctors. Later, public lectures (majlises), hospital training, and eventually formal schools (madrasahs) became common. Some students, like Ibn Sīnā, taught themselves. But generally, students were taught by a doctor who knew both theory and practice. Students usually paid a fee to their teachers. Some families became famous for generations of doctors, like the Bukhtīshū family, who worked for the Baghdad rulers for almost 300 years.

Before the year 1000, hospitals became popular places for medical education. Students would train directly under a practicing doctor. Outside the hospital, doctors would teach students in lectures at mosques, palaces, or public places. Al-Dakhwār became famous in Damascus for his lectures. He later oversaw all doctors in Egypt and Syria. He was the first to set up what could be called a "medical school" that focused only on medicine. It opened in Damascus in 1231 and existed until at least 1417. This was part of a larger trend of making all types of education more organized. Even with madrasahs, students and teachers often used all forms of education. Students would study alone, listen to teachers, work in hospitals, and finally study in formal schools. This led to a more standardized way of training doctors.

In 639 AD, Muslims conquered the Persian city of Jundi-Shapur. Most of its hospitals and universities were left untouched. Islamic medical schools were later built following these existing patterns. Medical education was taken very seriously, with detailed courses and clinical training.

Islamic medicine developed the "Bimaristans," or hospitals. They were very efficient and advanced. These hospitals served the public for free and without discrimination. They were advanced in how they operated, separating males and females and having different wards for different types of diseases.

Pharmacy

The profession of pharmacy became separate and well-defined in the early 800s, thanks to Muslim scholars. Islamic pharmacology (the study of medicines) grew from intellectual centers in Mesopotamia that encouraged the sharing of ideas. Indian and Far East influences came to Mesopotamia through trade routes. Mesopotamia is mostly present-day Iraq, which later became the Sasanian Empire. Persians kept Greek ideas alive, which then influenced Islamic pharmacology. In Islamic empires, pharmacology included all substances applied to the human body. Drugs, foods, drinks, cosmetics, and perfumes were all used for their medicinal properties. Drugs were often made from plants from different parts of Asia. Medicines were used to help keep the human body in balance. The Greek doctor Hippocrates is known for saying that sickness was an imbalance of qualities like cold, hot, dry, and moist. A special diet was often prescribed to restore this balance.

Al-Biruni said that "pharmacy became independent from medicine." Sabur Ibn Sahl, a doctor who died in 869, wrote the first book on pharmacy called Aqrabadhin al-Kabir. It was heavily influenced by Dioscorides' Materia Medica. Dioscorides was a famous Greek herbalist who worked with the Greek doctor Galen to categorize medicines. The Andalusian doctor Ibn Juljul organized substances from India, Southeast Asia, and the Indian Ocean. Substances were categorized based on where they came from: Greek, Indian, or Iranian. The knowledge of medicines' properties came from the pre-Islamic Sasanian empire and Persian culture, which focused on pharmacology. Islamic pharmacy developed a systematic way to identify substances based on their medical uses. Sabur also wrote other books, including one about replacing one drug with another. Even though his works were not officially enforced, they were widely accepted by doctors. The field of pharmacology grew from continuing and expanding on older civilizations' knowledge.

Women and Medicine

During the medieval period, Hippocratic writings became widely used by doctors. This was because they were practical and easy for doctors to access. Hippocratic writings on Gynecology (women's health) and Obstetrics (childbirth) were often used by Muslim doctors when discussing female diseases. The Hippocratic authors believed that women's general and reproductive health was linked to organs and functions that men did not have.

Beliefs about Women's Health

The Hippocratics blamed the womb for many women's health problems, including conditions like schizophrenia. They described the womb as an independent creature inside the female body. They believed that if the womb was not held in place by pregnancy, it would move to moist body organs like the liver, heart, and brain because it craved moisture.

Many beliefs about women's bodies and health in Islam can be found in religious writings called "medicine of the prophet." Much advice was given about the right diet to encourage female health, especially fertility. For example, quince was thought to make a woman's heart tender. Incense was believed to help a woman give birth to a boy. Eating watermelons during pregnancy was thought to make the child good-natured. Dates were to be eaten before childbirth to encourage sons and after to help the woman recover. Asparagus was believed to ease labor pain. Eating an animal's udder was thought to increase milk production in women. The pain and risks of childbirth were so respected that women who died during birth could be seen as martyrs. Prayers and invocations to God were also part of religious beliefs about women's health.

Infertility

Infertility was seen as an illness that could be cured. Unlike pain, infertility was not about how the patient felt. A successful treatment for infertility could be seen when a child was born. This allowed Arab medical experts to explain why some infertility treatments failed.

Miscarriage

Al-Tabari, inspired by Hippocrates, believed that miscarriage could be caused by physical or mental experiences. These experiences might make a woman behave in a way that harms the embryo, sometimes leading to its death depending on the stage of pregnancy. He thought that in early pregnancy, the fetus could be easily lost, like an "unripe fruit." In later stages, the fetus was more like a "ripe fruit," not easily affected by simple things like wind. Some physical and mental factors that could lead to miscarriage included breast injury, severe shock, exhaustion, and diarrhea.

Roles of Women in Medicine

There are examples of male guardians allowing male doctors to treat women. There are also examples of women seeking care from male doctors or surgeons on their own. Women also sought care from other women. The role of women as medical practitioners appears in several works, even though men mostly dominated the medical field. Two female doctors from Ibn Zuhr's family served the ruler Abu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur in the 1100s. Later, in the 1400s, female surgeons were shown for the first time in Şerafeddin Sabuncuoğlu's Cerrahiyyetu'l-Haniyye (Imperial Surgery). Treating women by men was sometimes justified by "prophetic medicine," which argued that men could treat women, and women men.

Female doctors, midwives, and wet nurses were all mentioned in the writings of the time.

Role of Christians

A hospital and medical training center existed at Gundeshapur. The city was founded in 271 by the Sassanid king Shapur I. It was a major city in Persia (today's Iran). A large part of the population were Syriacs, mostly Christians. Under the rule of Khosrau I, Greek Nestorian Christian philosophers found refuge there. These included scholars from the Persian School of Edessa (also called the Academy of Athens), a Christian university. These scholars came to Gundeshapur in 529 after their academy was closed. They worked in medical sciences and started the first projects to translate medical texts. Their arrival marked the beginning of the hospital and medical center at Gundeshapur. It included a medical school, a hospital (bimaristan), a pharmacology lab, a translation house, a library, and an observatory. Indian doctors also contributed to the school, especially the medical researcher Mankah. Later, after the Islamic invasion, the writings of Mankah and the Indian doctor Sustura were translated into Arabic in Baghdad. Daud al-Antaki was one of the last influential Arab Christian writers.

Cooperation happened during the Abbasid empire (750 AD) between Nestorian Christians from the Byzantine empire and the Abbasid rulers. Nestorian Christians escaped persecution and found financial support from the Abbasid rulers. Greek texts by Galen were brought by Christians and translated into Arabic for Islamic scholars and doctors to study. With the new combined civilizations, the Abbasid rulers wanted to gain knowledge from older societies. The Byzantine empire was seen as a modern society involved in medicine and pharmacology. The less strict Islamic view of Greek knowledge encouraged cooperation between Nestorian Christians and the Islamic empire. The Abbasid ruler al-Ma’mun is credited with promoting the translation of Greek texts, which helped medicine grow in the Islamic empires. The cooperation from Nestorian Christians was possible because there was no religious conflict about medicine. Christians and Muslims could work together without religious issues. Greek and Syriac texts were translated into Arabic as scientific learning moved from the Greek period to the Islamic empire. One of the most famous translators was a Nestorian Christian, Hunnayn b. Ishaq. He knew Syriac, Greek, Arabic, and had medical training. Hunnayn mainly translated works by the Greek doctor Galen. Hunnayn is known for creating a successful system for translating scientific texts.

Legacy

Medieval Islam's openness to new ideas and traditions helped it make big advances in medicine. It built on older medical ideas and techniques, expanded health sciences and hospitals, and improved medical knowledge in areas like surgery and understanding the human body. However, many Western scholars have not fully recognized its influence (separate from Roman and Greek influence) on the development of medicine.

By building and developing hospitals, ancient Islamic doctors could perform more complex operations to cure patients, especially in eye medicine. This allowed medical practices to grow and develop for the future.

The contributions of two major Muslim scholars and doctors, Al-Razi and Ibn Sina, had a lasting impact on Muslim medicine. By collecting knowledge into medical books, they greatly influenced how medical knowledge was taught and shared in Islamic culture.

Also, women made important contributions during this time. Records show female doctors, physicians, surgeons, wet nurses, and midwives.

See also

- Al-Tasrif

- Anatomy Charts of the Arabs

- Science in the medieval Islamic world

- De Gradibus

- Medical Encyclopedia of Islam and Iran

- Challenge of the Quran

- Commission on Scientific Signs in the Quran and Sunnah

- I'jaz

- Ibn Sina Academy of Medieval Medicine and Sciences

- Inventions in the Islamic world

- Iranian traditional medicine

- Islamic attitudes towards science

- Islamic bioethics

- Islamic views on evolution

- Islamic view of miracles

- Maimonides (Moshe ben Maimon)

- Miracles of Muhammad

- Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi

- Prophetic medicine

- Quran and miracles

- Unani

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |