History of hospitals facts for kids

The history of hospitals is a long and interesting journey, showing how people have cared for the sick and injured over thousands of years. It began in ancient times with special places for healing in Greece, Rome, and India. These early places, like the Asclepian temples in ancient Greece, were not like our modern hospitals. The Romans had military hospitals, but public hospitals as we know them didn't really exist until the Christian era.

A big change happened in the late 300s CE when the first Christian hospital was founded in the Byzantine Empire by Basil of Caesarea. Soon, many hospitals appeared in Byzantine society. Hospitals continued to grow and improve in Byzantine, medieval European, and Islamic societies from the 400s to the 1400s. Later, European explorers brought the idea of hospitals to new lands in North America, Africa, and Asia.

Today, St Bartholomew's Hospital in London, started in 1123, is thought to be the oldest hospital still working. It began as a charity and still provides free care. However, the Mihintale Hospital in Sri Lanka, built in the 800s, might be the oldest hospital with archaeological proof. It cared for monks and local people, showing early healthcare progress.

In the 1800s, Western missionaries helped set up the first hospitals in China and Japan. Over time, especially in the West, healthcare in hospitals became less about religion and more about science. World War I and World War II led to many new military hospitals and medical inventions. After World War II, governments in places like Korea, Japan, China, and the Middle East started running more hospitals. In recent times, large hospital groups and government health organizations have formed to manage hospitals, control costs, and share resources. Some smaller hospitals have closed because they couldn't keep up.

Contents

Ancient Hospitals and Healing Places

The very first places that tried to cure people were ancient Egyptian temples. In ancient times, hospitals were found in Greece, Rome, India, and Persia. In these early cultures, religion and medicine were often connected.

Healing in Ancient Greece

In ancient Greece, temples dedicated to the healing god Asclepius were called Asclepieia. These places were centers for medical advice, predictions about illnesses, and healing. They were special, controlled spaces designed to help people get better. The Romans later adopted the worship of Asclepius and built a similar temple in Rome.

At these shrines, patients would enter a dream-like sleep, almost like anesthesia. During this sleep, they hoped to receive guidance from the god in a dream. At the Asclepieion in Epidaurus, marble records from 350 BCE show the names, stories, and cures of about 70 patients. Some of the listed cures, like opening an infection or removing foreign objects, sound like real surgeries.

Even ancient navies had ships possibly used for healing. The Athenian Navy had a ship called Therapia, and the Roman Navy had one named Aesculapius. Their names suggest they might have been early hospital ships.

Hospitals in the Roman Empire

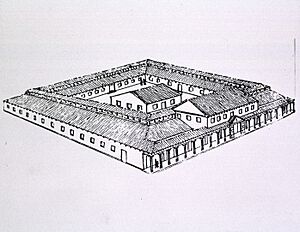

Around 100 BCE, the Romans built places called valetudinaria. These were for sick slaves, gladiators, and soldiers. Archaeologists have found many of these buildings.

A big change happened when Christianity became an accepted religion in the Roman Empire. This led to more care for the sick. After a meeting in 325 CE, hospitals began to be built in every city with a main church. Some of the earliest were built by Saint Sampson in Constantinople and by Basil of Caesarea in modern-day Turkey in the late 300s. By the early 400s, hospitals were common in the Christian East, a huge change from before.

Basil's hospital, called the "Basilias," was like a small city. It had housing for doctors and nurses, and separate buildings for different types of patients, including a special section for people with leprosy. Some hospitals even had libraries and training programs. Doctors wrote down their medical studies. So, in-patient medical care, like what we call a hospital today, was greatly influenced by Christian kindness and Byzantine ideas. Byzantine hospitals had chief doctors, professional nurses, and helpers. By the 1100s, Constantinople had two well-organized hospitals with male and female doctors, proper treatment plans, and special wards for different diseases.

Early Hospitals in India and East Asia

In ancient Sri Lanka, old writings from the 500s CE say that King Pandukabhaya built hospitals and birthing homes in the 300s BCE. This is the earliest written record of hospitals where many patients could stay and be treated. The oldest archaeological proof of a hospital in Asia is found in the ruins of Mihintale, from the 800s. Some experts think this might be one of the oldest hospitals in the world.

King Ashoka is said to have founded hospitals around 230 BCE. Early medical practices in India included Ayurvedic medicine. Some early Buddhist communities had monasteries that were also centers for learning medicine. While sick monks usually stayed in their own rooms, some monasteries had special rooms for them. Most of these rooms were only for monks, but some might have been open to the public.

The first clear mention of a real hospital in Southeast Asia comes from the traveler Fa Xian in the 400s CE. He described hospitals in the city of Pataliputra:

The kind and educated people of this country have opened a free hospital in the city. All poor or helpless people suffering from any illness come here. They are well cared for, and a doctor attends to them, with food and medicine given as needed. They are made very comfortable, and when they are well, they can leave.

Real archaeological proof of such hospitals appeared in the 700s and 800s. However, it wasn't a widespread system of hospitals back then. Instead, rulers sometimes supported medical care for people in certain places. In the 1100s, King Jayavarman VII of Cambodia set up a country-wide system of hospitals, linking them to the Buddha of healing.

Knowledge from Greece began to spread to Southeast Asia during the time of Alexander the Great in the late 300s BCE. While Tibetan medicine is often thought to be from China, it was actually quite influenced by Western medicine in the 600s and 700s. Persian and Arab doctors from the Islamic Caliphate were found across China during this time. Indian doctors might also have helped with one of the earliest Abbasid hospitals.

Hospitals from the 400s to the 1400s

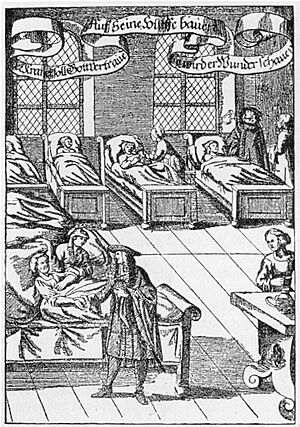

During the Medieval period, the word hospital meant many things. It included places for travelers, places to give help to the poor, clinics for the injured, and homes for the blind, disabled, elderly, and mentally ill. Monastic hospitals, run by monks, developed many treatments, both medical and spiritual.

Many hospitals were built in the 1200s. Italian cities led the way. Milan had at least twelve hospitals, and Florence had about thirty by the end of the 1300s. Some of these buildings were very beautiful. The Hospital of Siena, built for St. Catherine, has been famous ever since. This hospital building trend spread across Europe.

Hospitals also became common in France and England. After the French Norman invasion of England, many Medieval monasteries started a hospitium or hospice for pilgrims. This eventually grew into what we now call a hospital, with monks and helpers providing medical care for sick pilgrims and people suffering from diseases. Some believe the hospital, as we know it, was a French idea, first used to separate people with leprosy and plague, and later changed to help pilgrims.

A 12th-century account by the monk Eadmer describes how Bishop Lanfranc aimed to create these early hospitals:

But I must not conclude my work by leaving out what he did for the poor outside the walls of the city Canterbury. In short, he built a proper and large stone house…for different needs and comforts. He divided the main building into two, setting aside one part for men suffering from various illnesses and the other for women in poor health. He also arranged for their clothing and daily food, appointing helpers and guardians to make sure they had everything they needed.

Persian Hospitals

The Academy of Gondishapur was a hospital and medical training center in Gundeshapur in Persia. The city was founded in 271 CE. Many people there were Syriacs. Under King Khusraw I, Greek Christian scholars, including those from the Academy of Athens, found refuge in Gundeshapur in 529. They worked on medical science and started translating medical texts. This marked the beginning of the hospital and medical center at Gundeshapur. It had a medical school, a hospital (bimaristan), a pharmacy lab, a translation house, a library, and an observatory. Indian doctors also contributed to the school. Later, their writings were translated into Arabic in Baghdad's House of Wisdom.

Medieval Islamic Hospitals

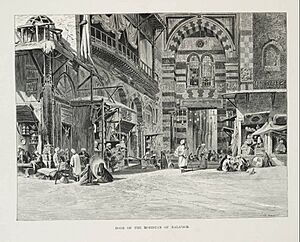

The first Muslim hospital was a place for people with leprosy, built in the early 700s. Patients were cared for and given money to support their families. The first general hospital was built in 805 CE in Baghdad by Harun Al-Rashid. By the 900s, Baghdad had five more hospitals. Damascus had six hospitals by the 1400s, and Córdoba had 50 major hospitals, many just for the military. Many early Islamic hospitals were started with help from Christians.

The United States National Library of Medicine says that the hospital, as we know it, came from medieval Islamic civilization. Unlike Christian places at the time, which mostly offered help to the poor and sick, Islamic hospitals were more complex. In Islam, it was seen as a moral duty to treat the sick, no matter how much money they had. Islamic hospitals were usually large, city-based, and mostly non-religious. Many were open to everyone: men or women, civilians or soldiers, children or adults, rich or poor, Muslim or non-Muslim.

Islamic hospitals served many purposes. They were centers for medical treatment, homes for patients recovering from illness or accidents, places for people with mental illness, and retirement homes for the elderly and weak.

A typical hospital had different departments, like for general diseases, surgery, and bone problems. Larger hospitals had even more specialties. Each department had a leader, a main doctor, and a supervising expert. Hospitals also had lecture halls and libraries. Staff included cleanliness inspectors, accountants, and other office workers. The Baghdad hospital had twenty-five staff doctors. Hospitals were usually run by three people: a non-medical manager, the head pharmacist (who had the same rank as the chief doctor), and the dean. Hospitals used to close at night, but by the 900s, laws made them stay open 24 hours a day.

For less serious cases, doctors worked in outpatient clinics. Cities also had first aid centers for emergencies, often in busy public places. There were also mobile units with doctors and pharmacists to help people in far-off communities. Baghdad even had a separate hospital for prisoners from the early 900s. The first hospital in Egypt, in Cairo, was the first known place to care for mental illnesses, and the first Islamic psychiatric hospital opened in Baghdad in 705.

Medical students would learn by helping doctors with patient care. Hospitals in this time were the first to require medical diplomas for doctors. The government's chief medical officer gave the licensing test. It had two parts: writing a research paper or a review of existing texts, and then answering questions in an interview. Doctors worked set hours, and their salaries were fixed by law. If a patient died, their family could show the doctor's prescriptions to the chief doctor, who would decide if the death was natural or due to carelessness. If it was carelessness, the family could get money from the doctor. Hospitals had separate areas for men and women, and some hospitals only treated women, with women doctors. Women doctors often focused on obstetrics (childbirth).

By law, hospitals could not turn away patients who couldn't pay. Over time, charitable foundations called waqfs were set up to support hospitals and schools. Part of the government's money also went to hospitals. Hospital services were free for everyone, and patients sometimes even received a small payment to help them recover after leaving. In the 1200s, a governor of Egypt, Al Mansur Qalawun, set up a foundation for the Qalawun hospital. It included a mosque, a chapel, separate wards for different diseases, a library for doctors, and a pharmacy. This hospital is still used today for eye care. The Qalawun hospital was in a former palace that could hold 8,000 people and served 4,000 patients daily. The rules stated:

...The hospital shall keep all patients, men and women, until they are completely recovered. All costs are to be paid by the hospital, whether the people come from far or near, whether they live here or are visitors, strong or weak, poor or rich, working or not, blind or seeing, physically or mentally ill, educated or not. There are no conditions for payment, and no one is refused or even hinted at for not paying.

The most famous doctors in the Medieval Islamic world were Ibn Sina (also known as Avicenna) and Al Rhazi (also known as Rhazes) in the 900s and 1000s.

Medieval European Hospitals

Medieval hospitals in Europe were similar to those in the Byzantine Empire. They were religious communities, with care provided by monks and nuns. An old French name for a hospital is hôtel-Dieu, meaning "hostel of God." Some were part of monasteries, while others were independent and had their own money, usually from land, to support them. Some hospitals served many purposes, while others were for specific needs, like hospitals for lepers, or shelters for the poor or pilgrims. Not all of them cared for the sick.

Around 529 CE, Saint Benedict established the first monastery in Europe at Monte Cassino. This monastery became a model for Western monasticism and a major cultural center. Saint Benedict wrote the Rule of Saint Benedict, which said that caring for the sick was a moral duty.

The first Spanish hospital, founded by the Catholic bishop Masona in 580 CE in Mérida, was a xenodochium. This was an inn for travelers (mostly pilgrims) and a hospital for local people. The hospital had farms to feed its patients and guests. Records show it had doctors and nurses who cared for the sick everywhere, "slave or free, Christian or Jew."

In 650, the "Hôtel-Dieu" was founded in Paris. It's considered by many to be the oldest hospital still working today. It was a multi-purpose place that helped the sick and poor, offering shelter, food, and medical care.

In the late 700s and early 800s, Emperor Charlemagne ordered that old hospitals that had fallen apart should be fixed. He also said that every main church and monastery should have a hospital.

By the 900s, monasteries played a big role in hospital work. The famous Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded in 910, set an example that was copied across France and Germany. Besides their own infirmary for monks, each monastery had a hospital for outsiders. These were run by the eleemosynarius, whose job was to help visitors and patients.

Because the eleemosynarius had to find the sick and needy nearby, each monastery became a center for helping those in pain. Many monasteries were known for this work.

Church leaders also made sure hospitals were provided. Bishops founded hospitals in cities like Cologne, Hildesheim, and Constance. Other churches also had hospitals. For example, in Trier, hospitals were named after the churches they were connected to. Between 1207 and 1577, over 150 hospitals were founded in Germany alone.

The Ospedale Maggiore in Milan, Italy, was built to be one of the first community hospitals. It was the largest project of its kind in the 1400s. Designed by Antonio Filarete in 1456, it's an early example of Renaissance architecture.

The Normans brought their hospital system to England when they conquered it in 1066. These new charitable houses became popular and were different from both English monasteries and French hospitals. They gave out help and some medicine, and wealthy people gave them money, hoping for spiritual rewards after death. Over time, hospitals became popular charitable places, separate from monasteries and French hospitals.

The main purpose of medieval hospitals was to worship God. Most hospitals had a chapel, at least one clergyman, and patients who were expected to help with prayer. Worship was often more important than medical care and remained a big part of hospital life even after the Reformation. Worship was seen as a way to ease the pain of the sick and ensure their salvation when a cure wasn't possible.

The second purpose of medieval hospitals was to help the poor, sick, and travelers. This charity included long-term care for the weak, medium-term care for the sick, short-term hospitality for travelers, and regularly giving money to the poor. While these were general acts of charity, the amount of help varied. Some places that saw themselves mainly as religious houses or places for guests would turn away the sick or dying, fearing that difficult healthcare would distract from worship. Others, however, like St. James of Northallerton, St. Giles Hospital of Norwich, and St. Leonard's Hospital of York, had specific rules saying they must care for the sick and that "all who entered with ill health should be allowed to stay until they recovered or died." Studying these three hospitals gives us an idea of the diet, medical care, cleanliness, and daily life in a medieval European hospital.

The third purpose of medieval hospitals was to support education and learning. At first, hospitals taught chaplains and priestly brothers reading and history. But by the 1200s, some hospitals started educating poor boys and young adults. Soon after, hospitals began to provide food and shelter for scholars in exchange for their help with chapel worship.

Hospitals in the 1500s and 1600s

Early Modern European Hospitals

In Europe, the old idea of Christian care changed in the 1500s and 1600s to a more non-religious approach. After King Henry VIII closed the monasteries in England in 1540, the church stopped supporting hospitals. Only after people in London asked directly, did the king give money to hospitals like St Bartholomew's, St Thomas's, and St Mary of Bethlehem's (Bedlam). At St. Bartholomew's, William Harvey did his research on blood circulation in the 1600s.

In Sweden, there were 28 asylums at the start of the Reformation. The king removed them from church control but allowed them to keep their property and continue their work under local government.

Across much of Europe, town governments ran small Holy Spirit hospitals. These had been founded in the 1200s and 1300s. They gave free food and clothing to the poor, helped homeless women and children, and provided some medical and nursing care. Many were attacked and closed during the Thirty Years War (1618–48).

In Denmark, modern hospital care began during a war (1675–79). Five government-run hospitals were founded. The government spent a lot on equipment and staff. Women nursed the wounded and sick soldiers, but men were always in charge. After Denmark lost the war, some hospitals were given to the Swedes, but those in Elsinore and Copenhagen continued.

Meanwhile, in Catholic countries like France and Italy, rich families kept funding religious houses that offered free health services to the poor. French practices were influenced by the idea that caring for the poor and sick was a necessary part of Catholic life. The nursing nuns believed that psychological and physical comfort, food, rest, cleanliness, and especially prayer were more important than just doctors and medicines.

In Protestant areas, the focus was more on the scientific side of patient care. This helped nursing become seen as a profession rather than just a religious calling. There wasn't much hospital development by the main Protestant churches after 1530.

Colonial American Hospitals

The first hospital in the Americas was the Hospital San Nicolás de Bari in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Its construction was approved in 1503 and finished in 1519. It was rebuilt in 1552 but abandoned in the mid-1700s. Today, it lies in ruins.

Conquistador Hernán Cortés founded the two earliest hospitals in North America: the Immaculate Conception Hospital and the Saint Lazarus Hospital. The oldest was the Immaculate Conception, now the Hospital de Jesús Nazareno in Mexico City, founded in 1524 to care for the poor.

In Quebec, Canada, Catholics ran hospitals continuously from the 1640s. Jeanne Mance founded Montreal's first hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal, in 1645. She hired sisters from a religious order to help run it. The General Hospital in Quebec City opened in 1692. These hospitals often treated diseases like malaria, dysentery, and breathing problems.

Hospitals in the 1700s

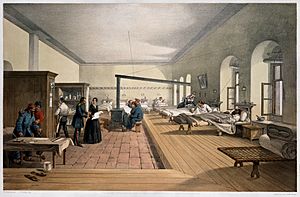

In the 1700s, during the Age of Enlightenment, modern hospitals started to appear. These hospitals focused only on medical needs and had trained doctors and surgeons. The nurses were not yet formally trained. The goal was to use new methods to cure patients. These hospitals offered more specific medical services and were founded by non-religious authorities. The difference between medicine and helping the poor became clearer. Inside hospitals, serious cases were increasingly treated separately, and different departments were set up for different types of patients.

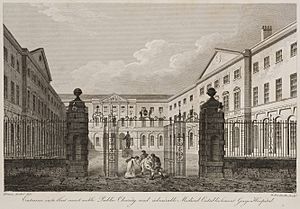

The idea of "voluntary hospitals" began in the early 1700s. Hospitals were founded in London in the 1710s and 1720s, like Westminster Hospital (1719) and Guy's Hospital (1724), which was funded by a wealthy merchant. Other hospitals appeared in British cities, many paid for by private donations. St. Bartholomew's in London was rebuilt in 1730, and the London Hospital opened in 1752.

These hospitals changed how hospitals worked. They started to become centers for new medical discoveries and the main places for training future doctors. Some of the best surgeons and doctors of the time worked and taught in these hospitals. They changed from being just shelters to complex places for providing medicine and care for the sick. The Charité hospital was founded in Berlin in 1710 by King Frederick I of Prussia because of a plague outbreak.

The idea of voluntary hospitals also spread to Colonial America. Bellevue Hospital opened in 1736, Pennsylvania Hospital in 1752, New York Hospital in 1771, and Massachusetts General Hospital in 1811. When the Vienna General Hospital opened in 1784 (becoming the world's largest hospital), doctors gained a new facility that grew into an important research center.

Another new idea from the Enlightenment was the dispensary. These places gave free medicines to the poor. The London Dispensary opened in 1696 as the first such clinic in the British Empire. The idea grew slowly until the 1770s, when many similar organizations appeared. Dispensaries also opened in New York (1771), Philadelphia (1786), and Boston (1796).

Across Europe, medical schools still mostly used lectures and readings. In their final year, students would get limited experience by following a professor through the hospital wards. Lab work was rare, and dissections were seldom done because of legal rules. Most schools were small.

Hospitals in the 1800s

In the mid-1800s, hospitals and the medical profession became more organized and professional. Hospital management became more structured. A law in 1815 made it required for medical students to practice at a hospital for at least six months as part of their training. An example of this change was the Charing Cross Hospital, started in 1818. By 1821, it was treating nearly 10,000 patients a year. It moved to a larger building and in 1866 added professional nursing staff.

Florence Nightingale helped create the modern profession of nursing during the Crimean War. She showed great compassion, dedication to patients, and careful hospital management. The first official nurses’ training program, the Nightingale School for Nurses, opened in 1860. Its goal was to train nurses to work in hospitals, help the poor, and teach.

Nightingale was key in changing hospitals. She improved sanitation (cleanliness) standards and changed the image of hospitals from places where the sick went to die to places focused on recovery and healing. She also stressed the importance of using data to see how successful treatments were and pushed for better management in hospitals.

In the mid-1800s, the Second Viennese Medical School became important with doctors like Carl Freiherr von Rokitansky and Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis. Basic medical science grew, and specialties developed. The world's first clinics for skin, eye, and ear, nose, and throat problems were founded in Vienna.

By the late 1800s, the modern hospital was taking shape, with many public and private hospital systems appearing. By the 1870s, hospitals were treating more than three times their original number of patients. In continental Europe, new hospitals were generally built and run with public funds. Nursing became a profession in France by the early 1900s. At that time, many hospitals were run by nuns. After 1900, the government tried to make public institutions less religious, which sometimes conflicted with the need for better medical care. New government nursing schools trained non-religious nurses for leadership roles. During World War I, many untrained middle-class women volunteered in military hospitals. They left after the war, but their involvement helped raise the status of nursing. In 1922, the government created a national nursing diploma.

In the U.S., the number of hospitals reached 4400 by 1910, with 420,000 beds. These were run by cities, states, federal agencies, churches, non-profit groups, and for-profit businesses. All major religious groups built hospitals. The 541 Catholic hospitals (in 1915) were mostly staffed by unpaid nuns. Non-profit hospitals were joined by large public hospitals in big cities and research hospitals often connected to medical schools. The largest public hospital system in America is the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, which includes Bellevue Hospital, the oldest U.S. hospital.

The National Health Service, which provides most healthcare in Britain, was founded in 1948 and took control of almost all hospitals.

Paris Medicine

Around 1800, Paris medicine greatly influenced how clinical medicine was practiced. New ways of physically examining the body became important, like tapping, looking closely, feeling, listening, and examining bodies after death. Paris was special because many medical professionals were in a small area, allowing ideas and new methods to spread quickly. One invention from Paris hospitals was Laennec's stethoscope. This invention brought even more attention to Paris.

Before the 1800s, the French medical system had many problems. A surgeon named Jacques Tenon wrote about issues like lack of space, inability to separate patients with contagious diseases, and general cleanliness problems. Also, a non-religious revolution led to the government taking over hospitals previously owned by the Catholic Church. This led to a call for hospital reform, which pushed for medicine to be less institutionalized. This contributed to the messy state of Paris hospitals, which eventually led to a new hospital system in a law passed in 1794.

The 1794 law was important for Paris Medicine because it aimed to fix some of these problems. First, it created three new medical schools because there weren't enough medical professionals for the growing French army. It also gave doctors and surgeons equal status in hospitals, whereas before, doctors were seen as smarter. This led to surgery being included in medical education, creating a new type of doctor who focused on pathology (the study of disease), anatomy (the study of body structure), and diagnosis. The new focus on anatomy was helped by this law, and pathological education was improved by using more autopsies to find the cause of death. Finally, the 1794 law provided money for full-time paid teachers in hospitals and scholarships for medical students. Overall, the 1794 law helped shift medical teaching from theory to practice and experience, all within a hospital setting. Hospitals became centers for learning and developing medical techniques, which was a change from the old idea of a hospital as just a place that accepted anyone who needed help, sick or not.

The next step in Paris medicine was creating an examination system. After 1803, this exam was required for all medical professionals to get a license, creating a standard system. This law also created another group of health professionals, mostly for people outside cities, who went through simpler, shorter training.

Another area influenced by Paris hospitals was the development of medical specialties. The way Paris hospitals were set up gave doctors more freedom to follow their interests and provided the necessary resources. For example, Philippe Pinel did a four-year study on how mentally ill women were hospitalized and treated at the Salpêtriére hospital. This was the first study of its kind by a doctor, and Pinel was the first to realize that patients with similar illnesses could be grouped, compared, and classified.

Protestant Hospitals

Protestant churches got involved in healthcare again in the 1800s, especially by creating groups of women called deaconesses who dedicated themselves to nursing. This movement started in Germany in 1836 when Theodor Fliedner and his wife opened the first deaconess motherhouse. It became a model, and within 50 years, there were over 5,000 deaconesses in Europe. The Church of England named its first deaconess in 1862.

William Passavant brought the first four deaconesses to Pittsburgh, in the United States, in 1849 after visiting Germany. They worked at the Pittsburgh Infirmary (now Passavant Hospital).

American Methodists made medical services a priority from the 1850s. They started opening charities like orphanages and homes for the elderly. In the 1880s, Methodists began opening hospitals in the United States, which served people of all religions. By 1895, 13 hospitals were operating in major cities.

Catholic Hospitals

In the 1840s–1880s, Catholics in Philadelphia founded two hospitals for Irish and German Catholics. They relied on money from paying patients and became important health and welfare places in the Catholic community. By 1900, Catholics had set up hospitals in most major cities. In New York, different Catholic orders set up hospitals mainly to care for their own ethnic groups. By the 1920s, they were serving everyone in the neighborhood. In smaller cities too, Catholics set up hospitals, like St. Patrick Hospital in Missoula, Montana. The Sisters of Providence opened it in 1873. It was partly funded by a county contract to care for the poor and also ran a day school and a boarding school. The nuns provided nursing care, especially for infectious diseases and injuries among the mostly male patients. They also tried to convert patients and bring lapsed Catholics back to the Church. They built a larger hospital in 1890. Catholic hospitals were largely staffed by Catholic nuns and nursing students until the number of nuns dropped sharply after the 1960s. The Catholic Hospital Association formed in 1915.

Chinese Hospitals

Traditionally, Chinese medicine relied on small private clinics and individual healers until the mid-1700s, when missionary hospitals run by Western churches were first established in China. In 1870, the Tung Wah Hospital became the first hospital to offer Traditional Chinese Medicine. After the cultural revolution in 1949, most Chinese hospitals became public.

New Technology and Advancements

Anesthetics

A major change in medicine was the introduction of anesthetics, used to put patients to sleep. Anesthetics became popular in the 1800s because they made operations easier and less painful. This meant surgeries like amputations were less deadly, as patients would stay still and lose less blood.

On November 7, 1846, the first amputation using a type of anesthesia called ether anesthesia was performed. This anesthetic, called letheon, was created by a dentist, Dr. William Morton. It was given to Alice Mohan for an amputation. The anesthetic reportedly took only three minutes to work fully. The amputation was done with little reaction from Alice Mohan, and she seemed completely unaffected by pain until a nerve was cut, when a small cry was heard. Very little blood was lost during the operation.

Antisepsis

Another big change was the idea of germ theory. This is the idea that diseases are caused by tiny living organisms entering the body. Joseph Lister applied germ theory to medical practice. He tried to show that germ theory should be taken seriously. At first, many didn't believe him because Lister said that airborne germs were infecting open wounds, and people didn't think this could be the only cause of infection.

Through experiments, Louis Pasteur showed that living organisms cause fermentation and that the spread of infections depended on living microorganisms. Joseph Lister applied this idea to surgeries. He used a carbolic acid solution to try to sterilize everything that would be on or near a wound. This method worked. Lister pointed out that even though his patients were often in smaller spaces than standard wards, they had a very low infection rate after he started using his methods.

Hospitals in the 1900s

After American cities grew quickly in the 1870s, the need for centralized care increased, leading to more voluntary hospitals. Inspired by religion or charity, these hospitals were admired. Being private, they got money from politicians and business people who wanted to gain public favor. With the ability to grow, hospitals began to compete for patients by offering more services and using new medical technology developed in the 1900s.

New Technology and Advancements

X-ray

In the year after the discovery of x-rays in 1895, many experiments were done for medical purposes. These included using X-rays during a surgery by John Hall-Edwards and on a broken wrist by Gilman and Edward Frost. Hospitals worldwide quickly adopted this new technology. In January 1896, the Glasgow Royal Infirmary in Scotland is credited with having the first radiology department. In America, the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia bought an X-ray machine in 1897.

See also

- Byzantine medicine

- Doctor of Medicine

- History of medicine

- List of the oldest hospitals in the United States

- Medieval medicine of Western Europe

- Nursing

- Timeline of nursing history

- Timeline of medicine and medical technology

Images for kids

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |