Simone Weil facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

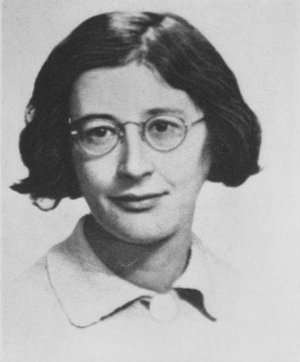

Simone Weil

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Simone Adolphine Weil

3 February 1909 Paris, France

|

| Died | 24 August 1943 (aged 34) |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | École Normale Supérieure, University of Paris (B.A., M.A.) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy

|

| School | Continental philosophy Marxism (early) Christian anarchism Christian socialism (late) Christian Mysticism Individualism Modern Platonism |

|

Main interests

|

Political philosophy, moral philosophy, philosophy of religion, philosophy of science |

|

Notable ideas

|

Decreation (renouncing the gift of free will as a form of acceptance of everything that is independent of one's particular desires; making "something created pass into the uncreated"), uprootedness (déracinement), patriotism of compassion, abolition of political parties, the unjust character of affliction (malheur), compassion must act in the area of metaxy |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Simone Adolphine Weil (born February 3, 1909 – died August 24, 1943) was a French philosopher, mystic, and political activist. She wrote many important works. However, most of her writings became famous only after her death.

After finishing her studies, Weil worked as a teacher. She taught for several years in the 1930s. She often took breaks due to poor health. She also wanted to focus on her political activism. She helped the trade union movement. She supported the anarchists during the Spanish Civil War. She even worked in car factories for over a year. This helped her understand the lives of working class people.

As she got older, Weil became more religious. She was drawn to mysticism. Her ideas are still studied today in many different fields. Her brother, André Weil, was a famous mathematician.

Contents

Simone Weil's Life Story

Early Years and Family

Simone Weil was born in Paris, France, on February 3, 1909. Her father, Bernard Weil, was a doctor. Her mother was Salomea "Selma" Reinherz. Her family was well-off and supportive.

Simone had an older brother named André Weil. They were very close throughout their lives. Simone was a healthy baby at first. But after six months, she got very sick with appendicitis. After that, she often had poor health.

When she was young, her father had to leave home. He served in the First World War. Some experts believe this experience made Simone very caring towards others. She showed great altruism throughout her life. Simone was a very loving person. However, she usually avoided physical touch, even with friends.

Growing Up and Learning

Simone was a very smart student. She knew Ancient Greek by age 12. She later learned Sanskrit. This allowed her to read the Bhagavad Gita in its original language. She was interested in many religions. She wanted to understand the wisdom in each one.

As a teenager, Weil studied with her admired teacher, Émile Chartier. She tried to get into the École Normale Supérieure in 1927 but failed. She succeeded in 1928. She was the top student in her philosophy exam. Simone de Beauvoir was second. During these years, Weil was known for her strong, radical ideas.

In 1931, she earned her master's degree in philosophy. Her thesis was about "Science and Perception in Descartes." She then became a philosophy teacher. This was her main job for most of her life.

Her Political Actions

Simone Weil often got involved in politics. She felt great sympathy for the working class. When she was just six years old, she refused sugar. She did this to show support for soldiers in World War I. At age 10, she said she was a Bolshevik.

In her late teens, she joined the workers' movement. She wrote political articles. She marched in protests. She fought for workers' rights. At this time, she believed in Marxism, pacifism, and trade unions. While teaching, she helped unemployed people and striking workers.

Weil never formally joined the French Communist Party. In her twenties, she started to criticize Marxism more. She was one of the first to say that powerful communist leaders could be as unfair as greedy capitalists.

In 1932, Weil visited Germany. She wanted to help Marxist activists there. But she thought they were not ready for the rising fascists. When she returned to France, her friends did not believe her fears. After Hitler came to power in 1933, Weil spent time helping German communists escape his rule.

She wrote articles about social and economic problems. One famous work was "Oppression and Liberty." She also wrote for trade union magazines. She criticized popular Marxist ideas. She also showed the limits of both capitalism and socialism. Leon Trotsky, a famous communist leader, even wrote back to her articles. He disagreed with her ideas.

In 1933, Weil took part in a French general strike. This strike protested job losses and low wages. The next year, she took a year off from teaching. She worked secretly in two factories, including one owned by Renault. She wanted to truly understand the working class. In 1935, she went back to teaching. She gave most of her money to political and charity causes.

In 1936, even though she was a pacifist, she went to the Spanish Civil War. She joined the Republicans. She saw herself as an anarchist. She wanted to go on a dangerous mission to rescue a prisoner. But the commander said no. He thought she would just sacrifice herself for nothing.

Instead, she joined an anarchist group called the Durruti Column. This group did risky "commando" missions. Simone was very short-sighted. This made her a poor shot. Her friends tried to keep her from missions. But she sometimes insisted on going. She only fought directly once. She shot at a bomber during an air raid. In another raid, she tried to use a heavy machine gun. But her friends stopped her. They thought someone less clumsy should use it.

After a few weeks, she burned herself while cooking. She had to leave the group. Her parents came to Spain to help her. They took her to Assisi to recover. About a month after she left, her group was almost completely destroyed in a battle. All the women in the group were killed.

Weil was upset by the killings done by the Republicans in Spain. She wrote about her experiences for a French newspaper. When she returned to Paris, she kept writing essays. These were about work, management, war, and peace.

Her Spiritual Journey

Simone Weil grew up in a family that was not religious. As a teenager, she thought about God. She decided that nothing could be known for sure. But in her own writings, she said she always had a Christian way of thinking. From a young age, she believed in loving her neighbor.

Weil became interested in Christianity around 1935. She had her first important religious experience in Portugal. She was moved by villagers singing hymns in a procession. Then, in 1937, she had a powerful spiritual experience in a church in Assisi, Italy. This was the same church where Saint Francis of Assisi had prayed.

A year later, she had a third, even stronger, experience. This happened while she was reading a poem. She felt that "Christ himself came down and took possession of me." From 1938 on, her writings became more mystical and spiritual. But she still focused on social and political issues.

She was drawn to Catholicism. But she chose not to be baptized at that time. She wanted to stay outside the church. She said this was because of her "love of those things that are outside Christianity." During World War II, she lived in Marseille. She received spiritual guidance from a Dominican friar. She also met the French Catholic writer Gustave Thibon. He later edited some of her work.

Weil was not only curious about Christianity. She was also interested in other religions. These included Greek and Egyptian mysteries, Hinduism, and Mahayana Buddhism.

Later Life and Death

In 1942, Weil traveled to the United States with her family. She did not want to leave France. But she agreed to go to keep her parents safe. She also knew it would be easier to reach Britain from the U.S. There, she could join the French Resistance. She hoped to be sent back to France as a secret agent.

She ended up doing desk work in London. This gave her time to write one of her most famous books, The Need for Roots. Some evidence now suggests she was trained to be a secret radio operator. But the plan was canceled because her health was getting worse.

The hard work she did took a toll on her health. In 1943, she was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Doctors told her to rest and eat well. But she refused special treatment. She had strong political beliefs. She also did not care much about material things. She limited her food. She ate only what she thought people in German-occupied France were eating. She probably ate even less, as she often refused food.

Her health quickly got worse. She was moved to a hospital in Ashford, Kent. After a life of fighting illness, Simone Weil died in August 1943. She was 34 years old. Her death was caused by cardiac failure.

Simone Weil's Writings

Simone Weil believed her writings were the best part of her. She thought they showed her true self, not her actions or personality. She said that looking at the lives of great people without their works "reveals their pettiness above all." This is because they put their best into their works.

Most of Weil's famous works were published after she died.

The Need for Roots

Weil wrote The Need for Roots in early 1943. This was just before she died. She was in London working for the French Resistance. She was trying to convince its leader, Charles de Gaulle, to create a group of nurses to serve on the front lines.

The Need for Roots had a big goal. It looked at France's past. It also suggested a plan for France's future after World War II. She carefully studied the spiritual and ethical problems that led to France's defeat. Then, she suggested ways to fix these issues for a future French victory.

Gravity and Grace

Gravity and Grace (La Pesanteur et la Grâce) is one of Simone Weil's most known books. But it was not meant to be a book. It is a collection of notes from her notebooks. Her friend, Gustave Thibon, chose and arranged these passages. Weil had given him some of her notebooks. But she did not intend for them to be published. So, Thibon's choices and editing greatly shaped the book.

Her Lasting Impact

During her lifetime, Simone Weil was known only to a small group of people. Even in France, her writings were mostly read by those interested in radical politics. But in the ten years after her death, she quickly became famous. People across the Western world paid attention to her.

For about 25 years in the mid-20th century, she was seen as one of the most important thinkers on religious and spiritual topics. Her ideas about philosophy, society, and politics also became popular.

Weil influenced many areas of study. She also deeply affected the lives of many individuals. Pope Paul VI said she was one of his three biggest influences. Weil's popularity started to go down in the late 1960s and 1970s.

However, more of her work was published over time. This led to thousands of new studies by experts on Weil. Some focused on understanding her religious, philosophical, and political ideas better. Others looked at how her ideas could be used in fields like classical studies, cultural studies, education, and even technical areas like ergonomics.

A study from the University of Calgary found that over 2,500 new scholarly works about her were published between 1995 and 2012.

Simone Weil in Film and Theater

"Approaching Simone" is a play by Megan Terry. It tells the story of Simone Weil's life, ideas, and death. This play won an award in 1969/1970 for Best Off-Broadway Play.

Simone Weil was also the subject of a 2010 documentary. It was made by Julia Haslett and called An encounter with Simone Weil. Haslett noted that Weil had become "a little-known figure, practically forgotten in her native France." She also said Weil was "rarely taught in universities or secondary schools."

The Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho also created a work about Weil. It was called La Passion de Simone (2008).

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Simone Weil para niños

In Spanish: Simone Weil para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |