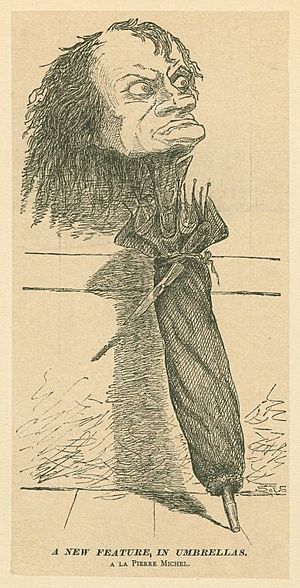

Louise Michel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Louise Michel

|

|

|---|---|

Louise Michel (c. 1880)

|

|

| Born | 29 May 1830 Vroncourt-la-Côte, France

|

| Died | 9 January 1905 (aged 74) Marseille, France

|

| Occupation | Revolutionary, teacher, medic |

| Known for | Activities in the Paris Commune |

| Signature | |

|

|

Louise Michel (born May 29, 1830 – died January 9, 1905) was a French teacher and a very important person during the Paris Commune. After being sent far away to New Caledonia, she became an anarchist. When she came back to France, she became a leading French anarchist and traveled all over Europe giving speeches. A journalist named Brian Doherty called her the "French grand lady of anarchy." She used a black flag at a protest in Paris in March 1883. This was the first time the black flag, now a symbol of anarchism, was known to be used.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Louise Michel was born on May 29, 1830. Her mother, Marianne Michel, was a maid, and her father was Laurent Demahis. Louise grew up with her grandparents, Charlotte and Charles-Étienne Demahis, in north-eastern France. She spent her childhood at the Château de Vroncourt and received a good education. After her grandparents passed away, she finished her teacher training and worked in small villages.

Becoming an Activist and Teacher

In 1865, Louise Michel opened a school in Paris. It was known for its new and modern teaching methods. She wrote letters to the famous French writer Victor Hugo and started publishing her own poems.

Michel became very involved in the political movements in Paris. She worked with important figures like Auguste Blanqui and Théophile Ferré. In 1869, a group called Société pour la Revendication des Droits Civils de la Femme (Society for the Demand of Civil Rights for Women) was formed. Louise Michel was a member. This group wanted to improve girls' education.

The group was also known as the Revendication des Droits de la Femme (Demand for Women's Rights). They worked closely with a group for male and female workers. In January 1870, Michel attended a funeral where she wished the event could have led to a big change in the government.

Louise Michel and the Paris Commune

During the Siege of Paris in 1870, Louise Michel joined the National Guard. When the Paris Commune was formed, she was chosen to lead the Montmartre Women's Vigilance Committee. In April 1871, she actively joined the fight against the French government. She was a close friend of Théophile Ferré, a leader in the Commune.

Michel fought with the 61st Battalion of Montmartre during the "Bloody Week." This was the final battle that ended the Commune. She also helped organize places where injured people could get help. She later wrote in her memoirs that she was very dedicated to the idea of revolution. On May 24, she gave herself up to the French army to protect her mother from being arrested.

Michel believed strongly in the revolution. She felt that women were just as capable as men in fighting for change. She wrote about how women often surprised her male comrades by being involved in the struggle. She challenged her friends to support women's rights after everyone had gained human rights.

In December 1871, Michel was put on trial by a military court. She was accused of trying to overthrow the government and using weapons. She bravely told the judges to sentence her to death, saying she would never stop fighting for freedom. The court sentenced her to be sent away to a far-off place. About 1,169 supporters of the Commune were also sent away.

Life in New Caledonia

After spending 20 months in prison, Louise Michel was put on a ship called Virginie on August 8, 1873. She was sent to New Caledonia, a French colony far away. The journey took four months. On the ship, she met Henri Rochefort, a famous writer, who became her friend for life. She also met Nathalie Lemel, another woman who was active in the Commune. It was Nathalie who helped Louise become an anarchist.

Louise Michel stayed in New Caledonia for seven years. She became friends with the local Kanak people. She learned about their stories, beliefs, and languages. She taught French to the Kanaks and supported them during their revolt in 1878. The next year, she was allowed to teach children of people who had been sent to New Caledonia. Many of these children were from Algeria.

Coming Back to France

In 1880, the French government allowed those who had been part of the Paris Commune to return home. Louise Michel came back to Paris, still full of revolutionary spirit. She gave a public speech on November 21, 1880. She continued her work in Europe, attending an anarchist meeting in London in 1881. There, she led protests and spoke to large crowds. She also met Sylvia Pankhurst, a young activist, in London.

In France, she worked with others to get permission for Algerian people who had been sent to New Caledonia to also return home.

In March 1883, Michel and Émile Pouget led a protest of unemployed workers. During this protest, Michel reportedly carried a black flag. This was the first time the black flag was used as a symbol for anarchism.

Michel was tried for her actions in the protest. She used the court to explain her anarchist beliefs. She was sentenced to six years in prison for encouraging the protest. Michel remained determined. She believed in a future where no one would be exploited. She was released in 1886.

Travels and Speeches

In 1890, Louise Michel was arrested again. After an attempt to send her to a mental hospital, she moved to London. She lived in London for five years. She opened a school for the children of political refugees. This school, called the International Anarchist School, opened in 1890. It taught children using scientific and logical methods. Michel wanted to teach children about kindness and fairness. The school closed in 1892.

Michel wrote for many English-speaking newspapers. Her writings were also translated into Spanish. She became a very well-known speaker, traveling across Europe and speaking to thousands of people.

In 1895, Sébastien Faure and Michel started a French anarchist newspaper called Le Libertaire. In the same year, Michel met Emma Goldman, another important anarchist, at a meeting in London. Goldman was very impressed by Michel.

Michel returned to France in 1895. In an article from 1896, she wrote that anarchism would help humanity escape its troubles. In 1904, Michel went on a speaking tour in Algeria.

Death and Legacy

Louise Michel passed away from pneumonia in Marseille on January 10, 1905. Her funeral in Paris was attended by more than 100,000 people. Michel's grave is in the Levallois-Perret Cemetery near Paris. The community still takes care of her grave. Her friend and fellow communard, Théophile Ferré, is also buried there.

Louise Michel's Ideas and Beliefs

Louise Michel's ideas changed over her life. She started as a progressive teacher. Her activism led her to believe in revolutionary socialism. But her experiences, especially after the Paris Commune failed, made her a strong anarchist. She came to believe that society needed to be completely changed to create a new, equal world. Her time in prison and in the French colony of New Caledonia greatly influenced her.

Michel's political ideas were shaped by the time after the French Revolution. This period saw different types of governments. Some believed that democracy was flawed. Others, like the Romantics, saw the revolution as a sign of the French people's spirit. By the 1840s, Romanticism in France became more political, focusing on social progress. Writers like Victor Hugo and Émile Zola wrote about the lives of the poor.

When Michel was born in 1830, a short revolt led to a new monarchy. This government focused on business but did little to help the working class. Michel first became known for speaking up for poor people and working women. In the 1860s, she strongly opposed the policies of Emperor Napoleon III. She often signed her writings with the name Enjolras, a revolutionary character from Hugo's Les Misérables.

In 1865, she wrote a new version of "La Marseillaise", a famous French song. In her version, Michel called for people to rise up and defend the republic. She believed that dying for the cause was better than defeat. This idea appeared in her poems, plays, and novels. Unlike others, Michel also spoke out against violence towards children and animals.

When Emperor Napoleon III was captured in 1870, the French Third Republic was declared. But the war continued, leading to a difficult siege of Paris. People suffered from hunger and cold. The government surrendered, but Michel and other Parisians formed a National Guard. When the Paris Commune was declared, Michel helped lead the Women's Vigilance Committee. She played a key role in trying to bring about economic and social changes. She pushed for the separation of church and state, education reforms, and workers' rights. These changes could not be fully carried out because the Commune lasted only a short time. When Michel was tried, she demanded to be executed, saying she would keep fighting if she lived. The court refused to make her a martyr.

Michel was imprisoned for two years before being sent away. While in prison, she insisted on being treated like other prisoners. She refused special help from friends like Hugo. She felt that special treatment would be a dishonor. During her four-month journey to New Caledonia, Michel thought deeply about her beliefs. She became an anarchist and, for the rest of her life, rejected all forms of government.

She learned about anarchism from a fellow prisoner, Nathalie Lemel. Michel became known for her kindness and generosity. In the colony, she lived simply, giving away her books, clothes, and money. She started teaching again. She spent time with the native Kanak people, teaching them French so they could stand up to the French authorities. Michel supported them in their fight against the colonial rulers.

In 1875, a new republican government was formed in France. The harsh crackdown on the Paris Commune affected French politics for years. Fear of another uprising delayed the return of those who had participated in the Commune. When Michel finally returned to Paris in November 1880, she was met by a crowd of 20,000 people.

Michel began her career as a public speaker and found audiences across Europe. In 1882, she wrote her first anarchist play, Nadine. As a speaker, Michel was good at explaining her arguments against capitalism and strict governments.

Michel often spoke about women's rights from an anarchist point of view. She supported education for women. She also believed that marriage should be based on choice and that men should not own women. In her later works, she imagined a new society where everyone was equal.

She believed that new technology would replace hard physical labor with machines. She argued that with anarchist ideas, this could lead to wealth being shared equally. In 1890, she thought that progress would make daily life easier. She believed that a few hours of enjoyable, voluntary work would be enough to produce everything needed. Michel did not think history was always getting better, but she believed it could. She argued that true progress came from learning, social development, and freedom.

Michel not only spoke about poverty but also criticized 19th-century capitalism. She pointed out problems with the capitalist banking system and predicted that large companies would harm small businesses and the middle class. In her memoirs, Michel said that the Anarchist Manifesto of Lyon (1883) expressed her views well. This manifesto was signed by Peter Kropotkin and others who became her friends.

Instead of focusing on violent revolution, Michel later emphasized that people would rise up on their own. She came to reject using terror to bring about a new era. She believed that "power is evil" and that history showed how free people became enslaved. In an 1882 speech, she said, "All revolutions have been insufficient because they have been political." She felt that formal organization was not needed because the poor would rise up and, by their sheer numbers, force the old ways to disappear.

Lasting Impact

Louise Michel was one of the most important French political figures in the late 1800s. She was also a powerful female political thinker. Her writings about fairness for the poor and working classes were read across France and Europe. When she died in 1905, thousands mourned her. Memorial services were held in France and London. Although her specific writings are less known today, her name is remembered in French streets, schools, and parks. Michel became a national hero in France and was called the "great citizen."

Before her death, the conservative French newspapers called Michel names like "the angel of petrol" and "queen of the scum." But others compared her to Joan of Arc because of her role in the Paris Commune. The image of Michel as the vierge rouge (red virgin) was used by historians when telling the story of the Paris Commune.

Michel is seen as a founder of anarcha-feminism. This idea combines anarchism with feminism. While some early anarchist thinkers had traditional views on women, Michel, Teresa Claramunt, Lucy Parsons, and Emma Goldman became important female figures in the anarchist movement of the late 1800s. The anarchist movement encouraged women to participate and supported the idea of women's freedom.

French feminists rediscovered Louise Michel in the 1970s. Academic interest in her life and writings also grew in the 1970s, thanks to a detailed biography by Édith Thomas.

The Louise Michel station on the Paris Metro is named after her. It is located in Levallois-Perret, where she is buried.

Louise Michel is also the subject of a graphic novel called The Red Virgin and the Vision of Utopia (2016).

In 2020, the street artist Banksy was said to have sent a rescue ship in the Mediterranean Sea and named it Louise Michel after her.

See also

In Spanish: Louise Michel para niños

In Spanish: Louise Michel para niños

- Anarchism in France

- Louise Michel Battalions – Spanish Civil War

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |