Giorgio Agamben facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Giorgio Agamben

|

|

|---|---|

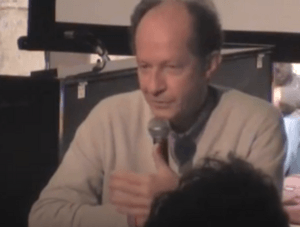

In 2009, during the presentation of Contributions à la guerre en cours

|

|

| Born | 22 April 1942 |

| Education | Sapienza University of Rome (Laurea, 1965) |

| Era | Contemporary philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy Philosophy of life |

|

Main interests

|

Aesthetics Political philosophy Social philosophy |

|

Notable ideas

|

Homo sacer State of exception Whatever singularity Bare life Auctoritas Form-of-life The zoe–bios distinction as the "fundamental categorial pair of Western politics" The paradox of sovereignty |

Giorgio Agamben (born April 22, 1942) is an Italian philosopher. A philosopher is someone who studies big questions about life, knowledge, values, and how we should live. Agamben is famous for his ideas about the "state of exception," "form-of-life," and "homo sacer." He also uses ideas from "biopolitics," which looks at how governments control people's lives.

Contents

About Giorgio Agamben

Agamben studied at the University of Rome. In 1965, he wrote a paper about the political ideas of Simone Weil, but it was never published. He also attended special seminars in the 1960s with the famous philosopher Martin Heidegger.

In the 1970s, Agamben focused on language, old texts, poetry, and medieval culture. During this time, he started to develop his main ideas, even though their political meaning wasn't clear yet. He also spent time at the Warburg Institute in London, where he began working on his second book, Stanzas (1977).

Agamben was friends with many important thinkers and artists. These included poets like Giorgio Caproni and José Bergamín, and the Italian writer Elsa Morante. He also worked with people like Pier Paolo Pasolini, a filmmaker, and Italo Calvino, a novelist.

His ideas were greatly shaped by other philosophers, especially Martin Heidegger, Walter Benjamin, and Michel Foucault. Agamben even helped edit Benjamin's writings in Italian. He once said that Benjamin's ideas helped him understand Heidegger better. In 1981, Agamben found some important lost writings by Benjamin in a library in Paris.

Agamben has also discussed the political ideas of the German lawyer Carl Schmitt, especially in his book State of Exception (2003). He has also learned a lot from the ideas of Michel Foucault.

Agamben's political thinking is based on old Greek texts by Aristotle, especially his works on politics and ethics. Later, Agamben joined discussions about the idea of "community." He suggested his own idea of a community in his book The Coming Community (1990).

Today, Agamben teaches at the Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio in Switzerland. He has also taught at other universities in Italy and has been a visiting professor at several American universities. In 2006, he won the Prix Européen de l'Essai Charles Veillon, an award for essays. In 2013, he received the Dr. Leopold Lucas Prize for his work.

Agamben's Main Ideas

Much of Agamben's work since the 1980s has been part of his "Homo Sacer" project. This project explores ideas about power, law, and human life. In this series of books, Agamben responds to studies on totalitarianism and biopolitics by Hannah Arendt and Michel Foucault. Since 1995, he has been known for this ongoing project. The books in this series were published in a different order than their numbering:

- Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (1995)

- State of Exception. Homo Sacer II, 1 (2003)

- Stasis: Civil War as a Political Paradigm. Homo Sacer II, 2 (2015)

- The Sacrament of Language: An Archaeology of the Oath. Homo Sacer II, 3 (2008)

- The Kingdom and the Glory: For a Theological Genealogy of Economy and Government. Homo Sacer II, 4 (2007)

- Opus Dei: An Archeology of Duty. Homo Sacer II, 5 (2013)

- Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive. Homo Sacer III (1998)

- The Highest Poverty: Monastic Rules and Forms-of-Life. Homo Sacer IV, 1 (2013)

- The Use of Bodies. Homo Sacer IV, 2 (2016)

In 2017, all these works were put together and published as The Omnibus Homo Sacer.

Agamben explains that a "form-of-life" is a way of living that cannot be separated from its shape or style. It's a life where you can't just take away the basic, simple existence.

If human beings were or had to be this or that kind of person, this or that destiny, no ethical experience would be possible… There is something that humans are and have to be, but this is not a fixed thing: It is the simple fact of one's own existence as possibility or potentiality…

– Giorgio Agamben

One of Agamben's main ideas is how life can be reduced to "biopolitics." This means that governments or powerful groups can treat human life as just a biological thing to be managed, rather than as individuals with rights. This is linked to his idea of homo sacer, a person who is reduced to "bare life" and loses all their rights.

Agamben's idea of homo sacer comes from an old Greek idea that separates "bare life" (zoê, meaning just living) from "a particular way of life" or "qualified life" (bios, meaning a life with a certain quality or purpose). In his book Homo Sacer, he talks about the concentration camps of World War II. He says that a camp is a place where the "state of exception" becomes the normal rule. The conditions in these camps were "inhuman," and the people held there were treated as if they were outside the normal rules of humanity.

Agamben believes that when a "state of exception" is created, people can lose their ability to speak up for themselves. They can lose their citizenship and control over their own lives. He says that the "state of exception" is about the power to decide over life itself.

In a state of exception, those with power decide who has bios (the life of a citizen) and who has zoê (the life of homo sacer). For example, Agamben would say that the Guantánamo Bay prison showed a "state of exception" in the United States after the events of 9/11.

Agamben points out that the basic human rights of people captured in Afghanistan and sent to Guantánamo Bay in 2001 were taken away by US laws. In response, some prisoners went on hunger strikes. When a person is placed outside the law in a state of exception, they are reduced to "bare life." In such a situation, a hunger strike can be a way for prisoners to resist, even though they have lost most of their power. During the hunger strikes at Guantánamo Bay, there were reports of forced feedings. Many medical experts said that forced feedings went against the prisoners' rights.

The Coming Community (1993)

In The Coming Community, Agamben explains his philosophical ideas about society and politics. He uses short essays to describe "whatever singularity." This means something that has a shared quality, but it's not about a fixed "essence" or nature. He explains that "whatever" doesn't mean "it doesn't matter," but rather "being such that it always matters."

Agamben starts by talking about what is "lovable":

Love is never directed toward this or that property of the loved one (being blond, being small, being tender, being lame), but neither does it neglect the properties in favor of a general love: The lover wants the loved one with all of its qualities, its being such as it is.

– Giorgio Agamben, The Coming Community

He also talks about "ease" as the "place" of love, or meeting a special moment. This connects to his later ideas about "use."

In this sense, ease perfectly describes that "free use of what is proper" that, according to Friedrich Hölderlin, is "the most difficult task."

– Giorgio Agamben, The Coming Community

Agamben uses other ideas to describe this "whatever" concept:

- Example – particular and universal

- Limbo – blessed and damned

- Halo – potential and actual

- Face – common and individual

- Threshold – inside and outside

- Coming community – state and non-state (humanity)

Other topics in The Coming Community include how the body is treated like a product, the idea of evil, and the concept of a "messianic" time.

Agamben doesn't completely reject ideas like subject/object or potential/actual. Instead, he looks at the point where they become hard to tell apart.

Matter that does not stay beneath form, but surrounds it with a halo.

– Giorgio Agamben, The Coming Community

He argues that humanity's political job is to show the hidden potential in this area where things are indistinguishable. He gives a real-world example of "whatever singularity" acting politically:

Whatever singularity, which wants to take hold of belonging itself, its own being-in-language, and thus rejects all identity and every condition of belonging, is the main enemy of the State. Wherever these singularities peacefully show their being in common there will be Tiananmen, and, sooner or later, the tanks will appear.

– Giorgio Agamben, The Coming Community

Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (1998)

In his major work, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, Agamben looks at an old and unclear figure from Roman law. This figure helps him ask important questions about law and power. Under Roman law, a man who committed a certain crime was banned from society and lost all his rights as a citizen. He became a "homo sacer" (sacred man). This meant anyone could kill him, but he could not be sacrificed in a religious ceremony.

Even though Roman law didn't apply to a Homo sacer in the usual way, he was still "under the spell" of law. This means that human life is "included in the legal system only by being excluded" (meaning, by being able to be killed). So, Homo sacer was both excluded from law and included at the same time. This strange figure is like a mirror image of the sovereign (a king, emperor, or president). The sovereign is both within the law (so they can be judged for crimes) and outside the law (because they can stop laws for a period of time).

Agamben uses Carl Schmitt's idea that the Sovereign is the one who can decide on the state of exception, where laws are "suspended" without being completely removed.

Agamben argues that laws have always had the power to define "bare life" (zoe, simple living) as different from bios (qualified life). They do this by excluding zoe, but at the same time, they gain power over it by making it something to be controlled politically. This power of law to separate "political" beings (citizens) from "bare life" (bodies) has continued from ancient times to today.

State of Exception (2005)

In this book, Agamben explores the idea of the "state of exception" (Ausnahmezustand), which was used by Carl Schmitt. He connects it to old Roman ideas of justitium (a time when courts were suspended) and auctoritas (authority). This helps him respond to Carl Schmitt's idea that sovereignty is the power to declare an exception.

Agamben's book State of Exception looks at how governments gain more power during times of crisis. During an state of emergency, constitutional rights can be reduced or ignored when a government claims this extra power.

The state of exception gives one person or government power and authority over others, going far beyond what the law usually allows. Agamben says that the "state of exception" is where logic and action become blurry, and pure violence claims to be right without any real reason. He points to Nazi Germany under Hitler as a long-lasting state of exception. He says that modern totalitarianism (where the government has total control) can be seen as a legal civil war that allows for the removal of not just political enemies, but whole groups of citizens.

The political power gained through a state of exception makes one government or part of a government all-powerful, operating outside the usual laws. During such times, certain types of information are seen as true, and certain voices are heard as important, while many others are not. This unfair difference is very important for how knowledge is created. The process of both gaining and stopping certain knowledge can be a harmful act during a crisis.

Agamben's State of Exception explores how laws being suspended during an emergency can become a long-term situation. He specifically looks at how this long state of exception can take away people's citizenship. When talking about the military order given by President George W. Bush on November 13, 2001, Agamben writes that it "completely removes any legal status of the individual, creating a being that cannot be named or classified legally." He notes that the Taliban captured in Afghanistan were not treated as prisoners of war under the Geneva Convention, nor were they seen as people accused of a crime under American laws. About 780 Taliban and Al-Qaeda fighters were held at Guantánamo Bay without trial. They were called "enemy combatants." Until July 7, 2006, these individuals were treated outside the Geneva Conventions by the United States government.

Auctoritas and Potestas

Agamben explains that auctoritas (authority) and potestas (power) are different, but they work together. He quotes Theodor Mommsen, who said that auctoritas is "less than an order and more than an advice."

Potestas comes from a social role, while auctoritas comes directly from a person's special status. This is similar to Max Weber's idea of charisma. Agamben uses examples from Roman and English history to show how a ruler's authority is linked to their ability to control their own death. He says that rituals involving two deaths for a ruler (as a normal human and then as a symbol) show people that the ruler controls both lives.

Agamben argues that the idea of auctoritas was very important in fascism and Nazism, especially in Carl Schmitt's theories. He says that modern leaders like the fascist Duce (Mussolini) or the Nazi Führer (Hitler) were not just constitutional leaders. Their qualities were directly linked to their personal being, following the idea of auctoritas, not just legal potestas.

Agamben believes that the difference between a dictatorship and a democracy can be very small. This is because governments have increasingly used "rule by decree" (making laws without the usual process) since World War I. Agamben often points out that Hitler never completely ended the Weimar Constitution. Instead, he suspended it for the entire time of the Third Reich using the Reichstag Fire Decree in 1933. This indefinite suspension of law is what defines the state of exception.

The Highest Poverty (2011)

In this book, Agamben studies medieval monastic rules. He connects these rules to ideas from Ludwig Wittgenstein's philosophy, especially "rule-following," "form of life," and the importance of "use." Wittgenstein believed that "the meaning of a word is its use in language," and he meant "language" to include any understandable behavior.

Agamben looks at earlier versions of "form-of-life" in the history of monastic life, starting with written rules in the fourth century. The book aims to show the difference between "law" and a special kind of rule that is the opposite of how laws are usually put into practice. To understand this idea, Agamben says we need "a theory of use – which Western philosophy doesn't even have the most basic ideas for."

Agamben turns to the Franciscans, a religious group, to study a unique time in history. This group organized itself with a rule that was their life. They thought of their lives not as their own property, but as a shared "use." He examines how this idea grew and how it eventually became part of the law of the Catholic Church.

Personal Views

Criticism of US Response to 9/11

Giorgio Agamben is very critical of the United States' response to the September 11, 2001, attacks. He believes that the US used these events to create a permanent "state of exception" as a way of governing. He warns against making the "state of exception" a common thing through laws like the USA PATRIOT Act. This, he says, means that martial law and emergency powers could become permanent. In January 2004, he refused to give a lecture in the United States. This was because under the US-VISIT program, he would have had to give his biometric information (like fingerprints). He felt this would reduce him to a state of "bare life" (zoe), similar to the tattooing done by the Nazis during World War II.

However, Agamben's criticisms are broader than just the US "war on terror." As he argues in State of Exception (2005), rule by decree has become common in all modern states since World War I, and has been used too much. Agamben points out a general trend in modern times. For example, when "judicial photography" was invented for identifying criminals, it was only used for them. But today, society is moving towards using this for all citizens, putting everyone under constant suspicion and surveillance. He notes that the Jews deportation in France and other occupied countries was made possible by photos from identity cards. Agamben's political criticisms lead to a larger philosophical look at the idea of sovereignty itself, which he believes is closely linked to the state of exception.

Statements on COVID-19

In an article published in February 2020, Agamben questioned the strong emergency measures taken for the COVID-19 situation. He quoted the Italian National Research Council (NRC) as saying there was no widespread COVID-19 epidemic in Italy at that time. He argued that the "health emergency was being exaggerated" to create a state of exception. Agamben's views were strongly criticized by other thinkers.

See also

In Spanish: Giorgio Agamben para niños

In Spanish: Giorgio Agamben para niños

- State of emergency: Use and viewpoints

- Basileus

- Homo sacer

- Interregnum

- Justitium

- Unlawful combatants

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |